What it's like to be in the police force and be LGBTQIA+

This is Part 1 of GMA News Online's series highlighting LGBTQIA+ issues in the police force and military.

Read Part 2 here: What it's like to be in the military and be LGBTQIA+

Read Part 3 here: Discrimination vs. LGBTQIA+ affecting opportunities, well-being —CHR exec

Lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgenders, queers or questionings, intersex, asexuals, and more — or the LGBTQIA+ community — are now living in a more hospitable world as the perception of acceptance of their sector has improved in over more than a decade. For the first time since 2006, Gallup’s global poll in 2023 showed that a majority of people at 52% said their country is a "good place" for gay or lesbian people to live.

LGBTQIA+ advocates have remained steadfast in their efforts to fight for equality and protection of the group across the globe. The Philippines was among the first countries in the Asia-Pacific region where groups for gays and lesbians were formally created. These groups began as social groups but became politically active in the 1990s.

One of the forms of discrimination faced by the LGBTQI persons in the country is in employment especially when a job does not fit the stereotypes tagged to the minority group.

Gay men are discouraged from joining the Philippine military as they might not fit in with the norms of the organization because they are commonly considered as “feminine” and “not real men.” The notion about a masculine soldier is strong, brave, alert, and decisive. Meanwhile, the notion about femininity, which is closely associated with being gay, is weakness, dependence, and the domination of emotion over reason.

This discrimination extends to the police service, which affects non-straight men who aspire to enter or have already become part of the police organization. Many police officers decided to hide their sexual identity from the organization and their colleagues to avoid different treatment.

Bullied during police training

But not this police nurse in Maguindanao del Sur.

Police Lieutenant Jessie G. Quitevis, 38, has been serving in the Philippine National Police (PNP) for around a decade already and is proudly out despite experiencing discrimination.

The police officer from Vigan City, Ilocos Sur said he experienced discrimination as soon as he applied to the PNP. According to Quitevis, a concerned citizen wrote a letter to the PNP questioning his entry to the organization citing only his sexuality. This was followed by more uncomfortable experiences while undergoing training.

“Pinatawag ako ng assistant instructor namin sa Ilocos, sa La Union. Tinatanong niya, ‘May kaso kaya yata,’ sabi niya sa akin. ‘Ano 'yun, Sir?’ sabi ko. ‘Bakit ka pinapa-imbestigahan?’ Sabi ko, ‘Ay, hindi ko po alam, Sir. Bakit?’ Tumawag ‘yung kuya ko. In-inform niya ako na there is something. ‘May kaunting problema kasi may nag-o-object ng pagka-enlist mo sa PNP.’ Kasi may sumulat daw na civilian na ako raw ay bakla, bakit ako mae-enlist sa PNP,” Quitevis said.

(Our assistant instructor in Ilocos, in La Union called for me. He asked, ‘Seems like you have a case.’ I asked, ‘What is it, Sir?’ He said, ‘Why are you being investigated?’ I said, ‘I have no idea, Sir. Why?’ My brother then called me and told me that there is something. ‘There’s a little problem because someone is objecting to your enlisting for the PNP.’ A civilian wrote [the PNP] and told them why should I be enlisted when I am gay.)

“’Yun ang pinaka-una kong struggle. Umpisa pa lang, struggle na. Sabi lang ng kuya ko, ‘Huwag mo lang isipin ‘yun. Hindi naman bawal. Wala naman sa Constitution na bawal ang bakla na pumasok sa PNP.’ So kung titignan mo sa memorandum ng [National Police Commission], wala ang sexuality. So pinagpatuloy ko,” he added.

(That was my very first struggle. It was just the start, and there was struggle already. My kuya just said, ‘Don’t think about it. It’s not prohibited. There is no provision in the Constitution saying gays are not allowed in the PNP. So if you will check the memorandum of [the National Police Commission], there is nothing on sexuality. So I continued [my application].)

During his training, Quitevis said that at first, he was scared that his classmates and instructors would learn about his sexual identity. He tried to conceal it by modulating a more masculine voice or talking less when speaking to them. But his co-trainees who knew him from high school and college outed him.

“Noong nasa training na ako, takot na takot ako ipakita na (bakla ako). Mino-modulate ko pa ‘yung boses ko talaga. Hindi ako masyadong nagsasalita that time kasi halata. Baka mahalata nila ‘yung boses ko na member ako [ng LGBT] so hindi ako nagsasalita talaga. Pero sa dami kasi ng aplikante, of course, may nakasabayan ako noong high school, noong college na kilala ako. Ini-spill nila ako, ‘Sir, si ano, beks ‘yan!’” Quitevis said.

(When I was in training, I was so afraid to reveal to them [that I was gay]. I would modulate my voice so it would be lower. I did not talk much that time because they might notice through my voice that I was a member [of the LGBT]. But due to the many applicants, of course, there would be someone who knew me from high school or college. They spilled, ‘Sir, he is gay!’)

Since then, Quitevis said he was treated as a form of entertainment and an object of laughter. He was asked to sing, dance, and dress as a woman. For him, it was not the kind of training he was looking for to enter the police organization. He was hurt.

“Every time na gusto nila ng entertainment, pinapapanhik ako sa stage, pinapakanta, pinapasayaw. Sa isip ko, okay lang, sige lang. Siguro it’s part of the training. Pero at the back of my mind, nadi-disappoint ako kasi hindi ito ‘yung klase ng training na gusto ko. Hindi ito ‘yung pinapangarap ko na training na maging katatawanan sa harap ng mga classmates ko na mga baguhang police. Meron pa ‘yung pinagdamit talaga ako ng pambabae nang meron kaming activity,” he said.

(Every time that they wanted entertainment, they would ask me to go on stage to sing and dance. In my mind, that’s okay. Maybe it was part of the training. But at the back of my mind, I was disappointed because this was not the kind of training I wanted. This was not the training I dreamt about because I was becoming the butt of jokes among my classmates who are newbie police personnel.)

“It hurts me a lot that time kasi sabi ko hindi deserve ‘yung ganito. Sabi ko, kasi ako professional ako. Dapat hindi na ginagawa ‘yun. ‘Yun talaga ang pinakatumataktak sa isip ko. Tapos tawa sila nang tawa. Pero kapag naiisip ko ngayon, tinatawanan ko na lang. Pero hindi talaga ‘yun mawala sa isip ko,” he added.

(It hurts me a lot that time because I told myself I don’t deserve this. I am a professional. They should not do this to me. That was what was in my mind. Then they would laugh and laugh. But when I think about it now, I just laugh it off. Yet I still cannot get that out of my head.)

According to Quitevis, some of the assistant instructors directed his classmates not to talk about his sexuality to anyone as he might be given extraordinarily hard tasks. Eventually, Quitevis said he started to gain respect from his classmates and instructors when they saw his capabilities in the training. As a former student leader in high school and college, Quitevis said he showed them his leadership skills. His instructors started giving him special assignments and his classmates also started asking for his help.

“It made me realize na ito ‘yung naging strength ko para ilabas kung ano ‘yung meron akong ability. Sabi ko hindi ako puwedeng maging ganito lagi na pagtatawanan nang pagtatawanan, na maging object of laughter ng mga ito. So ipinakita ko na meron akong brain, meron akong ability to lead,” he added.

(It made me realize that I would draw strength in showing my abilities. I said I cannot be like this always that I am the object of laughter of these people. So I showed them that I have a brain and I have the ability to lead.)

“Lumalabas ‘yung pagiging leader eme-eme natin. So every time na may problema, hindi ko napipigilan ‘yung sa sarili ko na mag-suggest. Napansin ng mga classmates ko na meron akong leadership skills so medyo nagbabago ‘yung tingin nila, na ‘yung level natin ay hindi pala doon lang, na meron pa tayong ibang maibubuga,” he said.

(My being a leader emerged. So every time there was a problem, I could not resist giving suggestions. My classmates noticed that I had leadership skills, so they started looking at me differently. They saw that I can go beyond a certain level.)

Then, the bullying ended.

“Eventually, natapos ‘yung pagbu-bully nila sa akin and I gained their trust and respect. So every time na meron silang problema, mga classmates ko, sa akin nila nilalapit kasi matapang daw ako humarap sa regional training director namin, which is sila takot. Ako kasi hindi. Naging advantage pa sa akin at naging advantage din ng mga classmates ko noon. So until now, kapag meron silang problema, nalalapitan pa rin nila ako,” he added.

(Eventually, their bullying ended. I gained their trust and respect. So every time they had a problem, my classmates would approach me because they said I am courageous enough to face our regional training director, of whom they are afraid. I was not afraid of him. It became an advantage for me and it became an advantage for my classmates too. So until now, whenever they have a problem, they would still approach me.)

Initially, Quitevis said his own family could not accept his sexuality not because of hatred but due to the fear he might be a victim of ridicule and harassment. According to him, they did not want him to end up as a hairstylist as that was the stereotypical job for homosexual men in the 90s. Due to this, he said his family used to beat him up to push him to be a straight boy.

“Against talaga sila. There were times na pinapalo nila ako noon. Gusto nila akong maging lalaki. That time kasi, 1990s, ang mga bakla kasi nababastos, sa parlor. Natatakot sila na baka magaya ako sa iba. Mostly kasi sa mga naging classmate nila noong elementary, nag-end up as a hairstylist. Tapos binabastos, tapos pa-Miss Gay-Miss Gay. Pero I am not belittling them kasi of course ‘yung mga hairstylist ngayon… Kasi ‘yung notion talaga noon, kapag bakla ka, wala kang mararating. Wala kang mararating sa buhay. ‘Yun kasi ‘yung culture na na-inculcate sa mga tao noon that time,” he said.

(They were really against [my being gay]. There were times they would spank me. They wanted me to be a man. At that time, the 1990s, the gays were not respected, they were only in [beauty] parlors. My family was afraid that I would be like them. Most of my classmates in elementary who were gay ended up as hairstylists. They were not being respected. They would join Miss Gay [pageants]. But I am not belittling those who do so because of course the hairstylists now… Before, the notion was if you were gay, you would not amount to anything. That was the culture inculcated in people that time.)

For Quitevis, this is the reason why some people are very critical of LGBTQIA+ members who are rising in their professional careers like those who become police officers.

“Kaya noong nagkaroon ng mga pagbabago, parang mahirap tanggapin na nagkaroon ng mga lawyers, nurses, politicians, pulis, sundalo na bakla. Bashing muna ‘yan. Eventually, bago nila natanggap nang buo. We are existing. We are professionals,” he said.

(So when changes started happening, it was at first difficult for some to accept that there are lawyers, nurses, politicians, police officers, and soldiers who were gay. There was bashing. Eventually, people accepted us. We are existing. We are professionals.)

Quitevis now serves as the provincial medical and dental team leader in Maguindanao del Sur under the PNP’s Regional Medical and Dental Unit of Bangsamoro Autonomous Region.

Destiny

Joining the PNP is like destiny for Quitevis, according to him. When he was born, his aunt said he could be a general because his umbilical cord and placenta coiled around his chest that it looked like a military sash.

“Alam mo parang ‘yun bang destiny kasi raw noong ipinanganak ako, ‘yung placenta nandito sa likod ko raw. Tapos ‘yung connection ng umbilical cord ko na ganyan daw (sa dibdib ko). Sabi ng auntie ko, ‘Magiging general ka paglaki mo!’ Noong nag-aaral ako kinukuwento ‘yun ng nanay ko. Sabi ko paano ako magiging general e hindi naman ako pulis. Wala nga sa hinagap ko ang pagpupulis kasi nga bakla tayo. Parang it’s a taboo na ‘yun ang pasukin mong trabaho. It’s a calling talaga,” he said.

(You know, it was like destiny because when I was born, my placenta was at my back. Then the connection to my umbilical cord was coiled around my chest. My auntie said, ‘You would be a general when you grow up!’ My mother would tell me that story when I was studying. I said how can I be a general when I am not even a police officer. Becoming a police officer did not enter my mind because we are gay. It was like taboo to enter that field. It’s really a calling.)

Quitevis took a nursing program in college because it was an in-demand course at the time and he wanted to work abroad. But it did not happen.

“Ang iniisip ko that time ‘yung magkaroon ng stable job na hindi ko na kailangang magbayad pa for my training. Sabi ng kuya ko, training ka lang diyan [sa PNP]. Kapag nakapasok ka while you are in training, may sahod ka na. ‘Yun ang gusto ko, makatulong talaga sa family. Kasi 28 na ako that time. Sabi ko, sige. Pikit-mata, sige, mag-apply tayo sa PNP,” he said.

(At that time, I was thinking of having a stable job wherein I need not pay for my training. My older brother said just take the [PNP] training. When you’re in and are already training, you will have a salary. That was what I wanted, to help the family. I was already 28 that time. I said, “Okay.” With eyes closed, I said I would apply to the PNP.)

Quitevis said he was inspired by the “Nameless, Faceless” recruitment slogan of the then PNP chief Police General Guillermo Eleazar in which the police organization ensured that only credentials will be considered in its hiring of police officers. According to him, he entered the police organization only through his hard work; he had no backer.

“Nag-start ako as police non-commissioned officer, PO1, patrolman. So noon nagkaroon ng lateral entry ang PNP. ‘Yung parang magja-jump ka from police non-commissioned officer to commissioned officer para maging opisyal. So tinry ko lang ‘yung luck ko,” he said.

(I started as non-commissioned police officer, PO1, Patrolman. So when lateral entry was allowed in the PNP – wherein you can jump from being police non-commissioned officer to commissioned officer – I tried my luck.)

“Noong time na ‘yun, si Sir Eleazar ang Chief PNP that time. Meron siyang slogan dati na ‘Nameless, Faceless.’ So regardless kung sino ka, kung saan ka galing, ano ka, basta qualified ka, bawal ang backer-backer that time. So pinalad ako na makapasok sa commissionship. At ang una kong designation is sa Health Service because I am a registered nurse. So natupad din ‘yung pangarap ko na maging police nurse through 2021 lateral entry,” he added.

(At that time, Sir Eleazar was the Chief PNP. He had a slogan dubbed ‘Nameless, Faceless’. So regardless of who you are, where you are from, what you are, as long as you are qualified, they would accommodate you. No backers were needed. So I was lucky enough to enter commisionship. At first I was assigned to the Health Service because I am a registered nurse. So my dream to be a police nurse eventually became a reality through lateral entry in 2021.)

Serving in BARMM

Quitevis was transferred to the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) in 2023, which he said was another challenge for him because the region was known then as an area of conflict among state troops, guerillas, and terrorists. Aside from this, he also felt homesick because his family was in Ilocos.

“Malayo sa family kasi taga-Ilocos Region pa ako. Makita mo ‘yung mapa, dulo-dulo. Kaya sabi ko, parte ‘yan ng pagiging uniformed personnel natin na malayo talaga sa family. So ‘yun ang challenge ngayon. Pero masaya naman kasi napagsisilbihan naman natin ‘yung mga Muslim brother and sister nating Bangsamoro,” he added.

(It was far from my family because we are from the Ilocos Region. If you look at the map, Ilocos and BARMM are on opposite ends. That is why I said part of being uniformed personnel is being away from the family. So that is the challenge now. However, I am happy because I get to serve our Bangsamoro Muslim brothers and sisters.)

“Another challenge na naman kasi mas mahirap doon kasi alam naman natin na ‘yung peace and order doon ganyan. Pero nagagawa naman natin nang maayos ‘yung trabaho doon. Nagkakaroon tayo ng maraming projects like medical missions sa iba’t ibang lugar sa Bangsamoro, particularly sa Maguindanao del Sur, Maguindanao del Norte, at saka sa Cotabato City. Ako kasi team leader. Ako [ang leader ng] provincial medical and dental team ng Maguindanao del Sur. Actually nag-start ko ng April, so one year and a month na ako,” he said.

(Another challenge is that it is harder there [in BARMM] because of the peace and order situation. But we can do the work well. We had many projects like medical missions in several areas in Bangsamoro, particularly in Maguindanao del Sur, Maguindanao del Norte, and Cotabato City. I am the team leader. I lead the provincial medical and dental team of Maguindanao del Sur. Actually, I started in April last year, so it has been one year and a month already.)

For Quitevis, one of his most memorable experiences as a police officer was their mission to the headquarters of former rebel group Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

“Eventually, naka-adapt ako ano man ‘yung kultura nila, kung ano ‘yung ginagawa nila. Parang nasuyod ko ang buong Maguindanao sa kasuluk-sulokan. Nagbabangka kami. Tumatawid kami ng dagat. Tumatawid kami ng ilog sa Liguasan Marsh para lang mapuntuhan ‘yung mga liblib na lugar. Tapos makapagbigay kami ng serbisyo sa mga tao doon like Operation Tuli, medical mission, magbigay kami ng gamot, mag-feeding program.

(Eventually, I was able to adapt to their culture. I was able to reach the whole of Maguindanao, it seems. We would take bancas to cross seas, even a river in Liguasan March just to reach remote areas. Then we would render services such as Operation Tuli and medical mission, and we would give medicines and conduct feeding programs.)

“’Yun siguro ‘yung isa sa mga maipagmamalaking karanasan ko na hindi nararanasan pa ng iba. At saka ‘yung pagpunta namin sa kuta ng mga MILF. Nakakatakot yun. ‘Sir, pupunta pala tayo magme-medical mission tayo.’ ‘Saan?’ ‘Sa kuta mismo ng MILF.’ So pagdating namin doon, nandoon ‘yung karatula na ‘Welcome to MILF headquarters’. Nandito pala tayo sa MILF headquarters. Pero ibang-iba na ngayon ang makikita mo, very peaceful na. Nakaka-proud na napasok mo na ‘yung headquarters ng MILF. Nakapagbigay ka ng serbisyo sa kanila at nakasama mo sila sa trabaho,” he added.

(I guess that is one of the experiences I am proud of that others have not experienced yet. And also the time we went to the MILF camp. That was scary. ‘Sir, we are going to have a medical mission.’ ‘Where?’ ‘In the camp of MILF.’ So when we arrived there, we saw the sign ‘Welcome to MILF headquarters’. We were actually there. But it’s very different now. It’s very peaceful. It made me feel proud to enter the MILF headquarters and render service to them and work alongside them.)

Pageant life

The life of Quitevis does not revolve around the police service only. He also engages in other activities to express himself as a member of the LGBTQIA+ community.

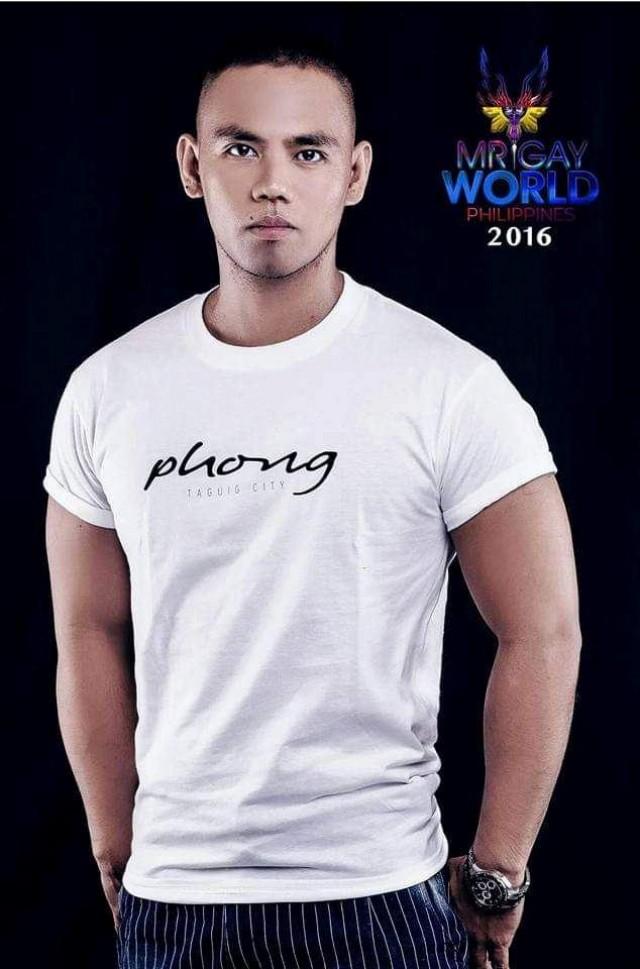

In 2016, Quitevis as a police officer joined Mr. Gay Philippines. His participation drew the attention of the public. While some expressed support and admiration for his endeavor, some threw criticisms at him.

“Sa pageant naman, naku, ito ‘yung nakakatakot talaga, talagang na-bash. It’s different kasi that time. Hindi pa ganu’n ka-open, 2016, ang LGBT sa men in uniform. Unlike ngayon, ang dami na makikita mo sa TikTok nagti-training na ‘yung ka-LGBT natin na naka-uniform na nagsasasayaw. ‘Yun ‘yung pinaka-struggle ko naman in the name of service,” he said.

(Joining a pageant would really make you the object of bashing. It was different at that time. People were not that open yet in 2016 to have LGBT among men in uniform. Unlike now, you would see in TikTok that LGBT members were in uniform and dancing while in training. That was my struggle in the name of service.)

Quitevis lamented that some negative comments came from professional individuals who were saying that he would be dismissed and that he was a “disgrace” to the uniformed service due to his participation in the pageant.

“Maraming negative comments doon. Some of them are, I just cannot imagine na ‘yung mga nagko-comment noon are professional. Sabi nila, ‘Ah, madi-dismiss na iyan sa service kasi saan ka nakakita ng men in uniform na nagladlad? Wala pang history of AFP or PNP. Disgrace siya sa service.’ Kasi dapat daw, connotations ba, na kapag men in uniform o nasa service ka, dapat brusko. Bawal ang mahinhin,” Quitevis said.

(There were many negative comments. Some of them, I just cannot imagine that they were professional. They would say, ‘Ah, he would be dismissed immediately because where in the world would you see men in uniform who were out and out gay? None in the history of the AFP or PNP. He’s a disgrace to the service.’ The connotation is that men in uniform should be brusque. To be gentle and feminine is not allowed.)

Despite the hate and challenges, Quitevis acknowledged that his story helps open the eyes of the public and the PNP that LGBTQIA+ persons can do the job in the police organization like their heterosexual counterparts.

“’Yung respect ng PNP as a whole sa mga LGBT members na katulad ko, that time kasi hindi talaga siya ganu’n ka-accepted. Pero ngayon accepted na accepted na ang mga LGBT. Siguro ‘yun ang pinaka-achievement na nagawa ko na. Naipamulat ko sa mga tao at sa mga PNP na may bakla, na may gustong pumasok sa PNP na hindi lang nila maibunyag ang sarili nila kasi natatakot sila sa maaring sabihin ng ibang tao. Pero nai-open up ko in public na we are existing,” he said.

(At that time, there was not much respect for LGBT members like me on the part of the PNP as a whole. But now LGBT members are very much accepted. Maybe that is one of my biggest achievements, to open the eyes of the people and the PNP that there are LGBT members who want to join the PNP. They are just hindered because of fear of backlash. But I was able to open up to the public that we are existing.)

In higher ranks in PNP

Aside from Quitevis, there are high-ranking officers in the PNP who are also members of the LGBTQIA+ community, according to PNP Recruitment and Selection Service Division chief Police Colonel Jonathan Pablito. He said they are respected by their peers because they do well in their jobs. Pablito said some LGBTQIA members in the PNP are “not explicit.”

“We have personnel both uniformed and non-uniformed personnel that are members of the LGBT. Siguro hindi lang sila explicit. Hindi rin naman kami nag-accounting kung sino ang LGBT. Siguro base sa napanood niyo na rin about Police Major Rene Balmaceda who is openly transgender and nag-succeed naman siya sa aming organization. Ang batayan talaga is ‘yung competency mo, ang galing mo sa trabaho,” he said.

(Maybe they are not so explicit. We do not have an accounting of LGBT personnel. You may have heard of Police Major Rene Balmaceda who is openly transgender and he succeeded in our organization. The basis really is competency, your excellence in your work.)

“Of course, we have the high-ranking PNP officers din na alam ng mga nakapaligid sa kanila that they are either gay or lesbian pero walang kaso ‘yun. Normal lang. Basta sila ay magaling sa trabaho, sila ay respetado,” he added.

(Of course, we have the high-ranking PNP officers who are known to those around them as either gay or lesbian. There is no problem there. It’s just normal. As long as they do their work, they are respected.)

Balmaceda is the first openly transgender cop in the police organization. She is in charge of the PNP Women and Children's Concern Division and Criminal Investigation and Detection Unit in Quezon City.

As young as four years old, Balmaceda said she knew she was different from other boys or girls. She said she used to wear the lipsticks of her sisters when they were away. After graduating in college for dentistry, Balmaceda said she applied for training at a police academy to follow in the footsteps of her sister, brother, and other family members.

Balmaceda said someone discouraged her from joining the training because it was masculine.

"Pero sa akin, walang problema sabi ko dahil kaya ko iyan. Ever since, hindi ko ikinahiya na isa akong ganito kasi ako talaga ito," she said in a vlog of Senator Mark Villar.

(But for me, there was no problem, I said, because I can do it. Ever since, I did not hide that I am [gay] because this is who I really am.)

"May mga discrimination nangyayari pero hindi through verbal. Ang ramdam ko is ano na lang, pagpapahirap. Kung halimbawa, times two ako palagi sa pahirapan na ginagawa. Pero hindi lang nila sinasabi na discrimination iyon. Pero so far nakayananan ko lahat," she said.

(There was some discrimination but it was not verbal. What I felt was added hardship. For instance, I have to do twice what is expected. But they do not refer to it as discrimination. But so far, I was able to endure all.)

Application

The PNP has no recruitment policy that discriminates against the LGBTQIA+ community, Pablito said. As long as the applicants meet the qualifications, they will be considered as candidates.

An applicant must be a Filipino citizen, not less than 21 years but not more than 30 years old, and a bachelor's degree graduate. Pablito added that the PNP does not consider a police officer’s sexual identity even for schooling, assignments, and promotions. Their only basis is competency and fitness.

Even if there are objections to the entry of LGBTQI persons to the PNP citing their sexuality, Pablito said the police organization will dismiss these appeals like what happened with the letter against Quitevis when he was about to be a part of the institution.

“Ang mga sinasala po nating ganyan is meron tayong complete background investigation. Definitely, hindi ‘yung sexual orientation ang puwedeng i-reklamo. Ang puwedeng i-reklamo diyan, ‘yung criminal record o ikaw ay maraming reklamo sa barangay. Even sa [character background investigation], tinatanong ‘yung mga kapitbahay o sa school. Hindi lang tayo nagbi-base sa sina-submit doon. Talagang ‘yung complete background investigation,” he said.

(We do a background investigation on applicants. Definitely, sexual orientation is not one of the complaints that we will look into. If you have a criminal record or a complaint filed against you in the barangay, then we will look into that. Even in character background investigation, we ask neighbors or schoolmates. We do not just base it on complaints filed. We do a complete background investigation.)

“Marami nang natanggal dahil doon. Malaman-laman mo doon sa kanilang barangay ay siya ‘yung pasimuno ng kaguluhan. So nobody is disqualified dahil lang sa kaniyang sexual orientation. Ibig sabihin kung nakapasok siya, ibig sabihin hindi kinonsider ‘yung reklamo sa kanya dahil sa kanyang sexual orientation,” he added.

(Many were not allowed to join the PNP due to results of background investigations. Someone might have been reported in the barangay as a lead troublemaker. So nobody is disqualified due to sexual orientation. We do not give weight to complaints regarding applicants’ sexual orientation.)

While the PNP is open to accepting LGBT as members, he admitted that they still have to wear a police uniform set for their biological sex and not their sexual, gender identity, or expression. Transgender women have to wear the police uniform prescribed for biological males. Transgender men have to wear the police uniform prescribed for biological females.

“We are uniformed organization so pagdating sa trabaho (when it comes to work), we follow prescribed uniform. Ang batayan po doon is ‘yung biological sex. Sa lahat naman ng LGBT na kasama namin sa trabaho, wala namang nagrereklamo, tanggap naman nila ito. Pero outside work, wala rin naman pong polisiya. May tinatawag lang tayong norms. Not only for PNP, but also for government officers. We are encouraged to dress appropriately and modestly. Kasama na diyan ‘yung walang ostentatious display. Kasama din diyan ‘yung pagdadamit na overtly sexual. Ito ay hindi lang pang-transgender, this is for heterosexual,” he said.

(The basis there is biological sex. Among all the LGBT personnel we have, no one complained about this policy. Outside work, there is no policy [as to what to wear]. But there are norms. Not only for PNP, but also for government officers. We are encouraged to dress appropriately and modestly. This includes not having ostentatious display or wearing overtly sexual clothes. This covers not just transgenders, but also the heterosexuals.)

According to Pablito, the PNP is not keeping track of who among their personnel are in homosexual relationships. He said some lower units of the police organization attempted to conduct an accounting of LGBTQI persons in the institution but it was stopped following a backlash. He said the PNP does not even have such a policy at the national level.

“With regards to relationships, makikialam lang po ang PNP kung may reklamo. Kumbaga may pambubugbog, ganu’n. Kapag nirereklamo ka na hindi ka nagsu-support. So doon lang po makikialam ang PNP. Pero sa inyong personal relationships is wala po. I’ve heard and I’ve read na may mga units na in the past sinubukan nilang mag-accounting kung sino ‘yung mga ganiyan. Sila ay nabatikos pero na-correct kasi wala namang lumabas na overall na PNP-wide na move. Sa 23 years ko sa service, wala pa po akong na-e-encounter na ganiyang pag-aaccount kung sino gay, lesbian, transgender sa aming hanay,” he said.

(With regards to relationships, the PNP will only look into them if there is a complaint, like violence or refusing to give financial support, for instance. But regarding personal relationships, the PNP will not bother to meddle in them. I’ve heard and I’ve read that tehre were units in the past that tried to do an accounting of LGBTQI persons. This did not prosper because there was no order to do such throughout the whole PNP. In my 23 years in the service, I have not encountered any accounting made of gay, lesbian, and transgender in our ranks.)

Pablito noted some milestones in the protection of LGBTQIA+ persons within and outside the police organization in recent years such as the establishment of gender-focused offices, desks, and programs. Aside from these, Pablito said the enforcement of the Safe Spaces Act also helps in securing the safety of the sector as it prohibits misogynistic, homophobic, and transgender remarks. For him, the development in LGBTQIA+ concerns is tied with the advancement of women in the PNP.

“Kumbaga this is a man’s world. Pero ngayon, way back in the 90s, nabuo na itong gender development… Meron kaming Children and Women Protection [desks] sa lahat ng istasyon sa buong Pilipinas. At ang mga nakatao diyan ay mga females. ‘Yung mga cases po involving din itong mga LGBT is sila rin po nagha-handle. Ibig sabihin sila po ay equipped pagdating kung ano ang latest. Kumbaga, nakisabay naman ang PNP sa mga development pagdating sa gender, how to handle these sensitive issues,” he said.

(In a sense, this is a man’s world. But now, since way back in the 90s, there are Children and Women Protection desks in all police stations in the Philippines. Females are the ones on duty there. They also handle cases involving LGBT. That means they are equipped to deal with the latest. The PNP thus in a way has kept up with the developments when it comes to gender, and as to how to handle sensitive issues.)

“Sa aming training, sa lahat ng trainings namin ngayon, mapa-specialized training or mandatory training, ay merong module sa gender and development at palaging kami ay pinapaalalahanan na iba ‘yung biological sex at iba ang gender identity. Ngayon naman is nagiging open tayo sa lahat naman ng pulis ngayon either may kaibigan o may kapamilya ring LGBT. We are keeping up with the times din naman and nagiging more accepting,” he added.

(In our training programs, whether specialized or mandatory, there are modules on gender and development. We are always reminded that biological sex is different from gender identity. We in the police force are open to having family or friends who are LGBT. We are keeping up with the times and have become more accepting.)

In the Philippines in 2009, the PNP expressed openness in recruiting gays in the uniformed service. In 2018, Senior Inspector Rene Balmaceda became the first openly transgender cop in the country.

A 2023 published survey showed that police officers neither agree nor disagree with including gay and bisexual men in the PNP. This neutral response implies a lack of strong or definitive opinions about the LGBT struggle, according to the researchers. This may also indicate uncertainty, a need for further awareness, or potential openness to the idea of inclusivity, they added. —KG/RSJ, GMA Integrated News