Filtered By: Topstories

News

Special Report: Rape in the Philippines: Numbers reveal disturbing trend

By AGATHA GUIDABEN, GMA News Research

It was an early Saturday morning in Mandaluyong, at the corner of a street that bears the name of Noli’s tragic heroine. A 17-year-old girl, naked and crying, tumbled out of a gray sedan; she had been raped.

The girl’s ordeal occurred just hours before rape-slay victim Anria Espiritu was laid to rest in Calumpit, Bulacan. Espiritu, 26, was found dead the week before; her body bore multiple stab wounds, and authorities believe she may have been raped by more than one assailant.

Espiritu and the teenager's cases are the most recent to hit the headlines. However, rape incidents reported in the news are far fewer compared to those actually reported to authorities.

In 2013, the Philippine National Police Women and Children Protection Center (PNP-WCPC) recorded a total of 5,493 rape incidents involving women and child victims. That’s approximately one reported rape incident every 96 minutes.

But consider this: the PNP-WCPC is just one of several units that report crime data. Its mother unit, the PNP Directorate for Investigation and Detective Management (PNP-DIDM), consolidates crime reports from all reporting units. Last year, the PNP’s annual report based on DIDM data tallied as much as 7,409 reported rape incidents, or one every 72 minutes.

Consider, too, that these are just the reported rape incidents.

The Center for Women’s Resources (CWR), an institution advocating women empowerment since 1982, said that official data on rape incidents could actually be underreported.

“Batay sa aming experience, ang isang nabibiktima, lalo na 'pag bata, 'di kaagad siya nagkukuwento. Lalo na 'pag tinatakot,” said CWR Executive Director Jojo Guan in an interview with GMA News Research.

“Pina-process din muna ng isang rape victim sa sarili niya kung anong nangyari sa kaniya. At usually, ano yun, talagang depression muna. Kaya isang brave step 'pag ikaw ay nakapag-report,”she added.

(“Based on our experience, a rape victim – more so a child rape victim – does not immediately report her ordeal, especially when she’s being threatened… the rape victim tries to process what happened to her, and usually, depression sets in. Reporting the rape is already a brave step on the victim’s part.”)

While it’s difficult to quantify the extent of unreported rape incidents, Guan said it was evident when CWR got to talk to people during community orientations on violence against women and children.

“Maraming nagkukuwento, tapos kung minsan nga in third person — ang kapitbahay namin… may kaibigan ako… 'Pag tinanong mo, nasabi nyo po ba to sa barangay o pulis? Hindi,” she recounted. “Kasi nga natatakot, o iniisip nila na nakakahiya. Kaya sa ganun pa lang, sa marami na naming nakakausap, ibig sabihin marami pa ring hindi pumupunta,” Guan added.

(“A lot of people tell us, sometimes they recount their stories in third person – ‘our neighbor…’, ‘I have a friend…’. When we ask them whether they reported the incident to the barangay or to the police, they would say no… They are scared, they are ashamed. Those anecdotes that we get from the people we’ve spoken to mean there are still many who do not go [to authorities].”)

Available official data on those that did report their rape reveal a disturbing trend. Based on data in the past 15 years, three out of four rape incidents reported to the PNP WCPC involved child victims.

A much smaller dataset from the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) show that nearly half of the child rape cases that they served last year involved children younger than 14 years old.

Earlier this month, a man in San Juan City was caught on CCTV carrying off an 11-month-old baby girl who was later found dead under a jeepney. Medico legal findings show evidence that she was raped.

PNP WCPC Chief Juanita Nebran explained that children are indeed more vulnerable to abuse. “Sila yung walang kakayahang lumaban... takot sila, at andyan pa yung hiya,” she told GMA News Research in a phone interview.

(“[The children] do not have the capability to fight back… they are scared, and at the same time they are ashamed.”)

CWR’s Guan shared a similar observation, adding that an adult rapist would take advantage of a child’s submissive nature.

“Nakikita niya na ‘ito, ay hindi ito lalaban sa 'kin… magagawa ko lahat ang gusto ko sa kaniya,” she said. (“He sees that the child victim will not fight back, and that he can do anything he wants with the child.”)

The PNP WCPC data also show an increasing trend in reported rape incidents in recent years. Last year’s figure (5,493, already mentioned in an earlier paragraph) was a record high coming from 3,294 reported women and child rape incidents way back in 1999. The 15-year average chalks up to 3,889 reported rape incidents per year.

Nebran attributed this trend to a number of factors. One is that as the population grows, so does the likelihood of more crimes to be committed. Another is that the PNP in recent years has been striving to get the “true crime picture.” This meant that crime reports now included those coming from barangay blotters and other law enforcement units, not just data from police units.

While the thought of increasing reports of rape may sound horrific, it indicates that victims are becoming bold enough to come out.

“Meron kaming ginagawang advocacies sa schools, sa communities, ina-advocate namin na 'wag silang matakot, 'wag mahihiya, lumabas na kayo, mag-report kayo,” Nebran said. “So mas nakaka-reach out kami, kaya mas marami nang nag-re-report.”

(“We conduct these advocacies in schools and in communities, we advocate that victims should not be scared, that they should not be ashamed, that they should come out and report. We can reach out to them more, so more are also reporting to us.”)

“Hindi naman sa wala kaming ginagawa kaya lumalaki yung bilang. Marami na kaming kakayahan ngayon, maraming agencies na tumutulong. Hindi naman po kami nagpapabaya,” she added.

(“It’s not that [the rape incidents] are increasing because we’re not doing anything about it. We are now more equipped, there are more agencies helping us. We’re not being lax at our jobs.”)

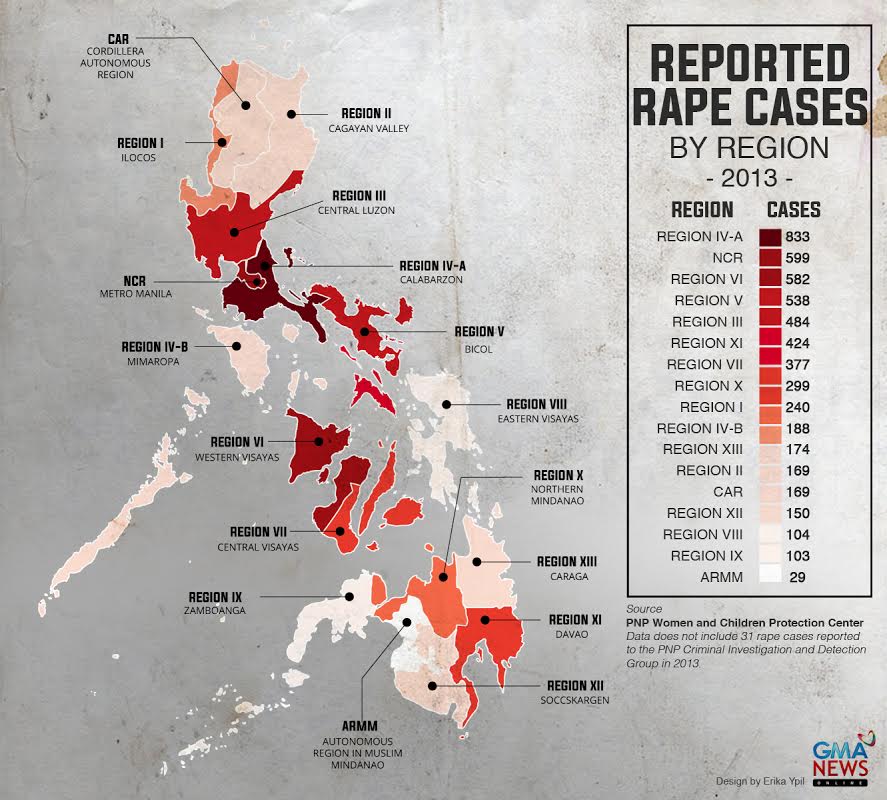

The reported rape incidents based on last year’s PNP WCPC data are highest in CALABARZON and the National Capital Region. Except for ARMM which tallied only 29 incidents, all regions recorded more than a hundred incidents.

“Kung mataas nga ang awareness dun sa community na ito ay pwedeng ihapag sa barangay o sa pulis, mas marami ang ma-re-report. Kaya kung titingnan mo rin, marami sa NCR. Kasi dito, maraming awareness-raising, at yung nearby communities,” Guan said.

Guan said while other areas were just as likely to have a high rape incidence, the statistics may not necessarily bear this out. She said the “culture of silence” strongly prevailed in those areas, especially in the Muslim provinces.

(“If the awareness in a community is high, if they know that they can approach the barangay or the police, then more victims will report. If you’re going to look at the data, there are more reported cases in NCR. That is because there are a lot of awareness raising activities here and also in the nearby communities.”)

Those who do decide to report their rape face even more challenges, according to Guan. A rape victim’s resolve to take action may be affected by how her family and the attending authorities would handle her delicate situation.

“Mas kailangan talaga nila ng suporta at pang-unawa lalo na ng malalapit sa kanila. Pero kung yung mga mas pinakamalalapit sa kanila ang siyang nang sumuko at umurong... lalo na pag menor de edad tapos yung nanay o tatay pa ang kulang sa support system, ang isang biktima ng rape ay talagang uurong,” she said.

(“Rape victims need the support and understanding of the people close to them. But if those closest to them are the ones who give up and back out… especially in the case of minor victims whose parents lack that support system, a rape victim will really back out.”)

CWR has observed cases where authorities asked judgmental questions -- “Bakit kasi gabi ka na umuwi? Ano ba yung damit mo? Bakit di ka nagpasama?... Bakit ka nakipag-inuman doon, kababae mong tao?” – that made rape victims blame themselves for what happened to them.

(“Why did you come home late? What clothes were you wearing? Why didn’t you ask someone to accompany you? You’re a girl… why did you join the drinking session?”)

And then there is the matter of whether to push through with filing a case or not against the assailant. Victims who have no financial means are particularly handicapped when it comes to seeking justice, Guan said.

“Ang iisipin nila, pa'no ba yung lawyer, yung pagbabayad nun, yung pagbabyahe sa korte. Yung sistema mismo natin ay hindi nag-e-encourage na mag-pursue ang isang biktima ng kaso dahil napakabagal ng justice system, napakabagal ng decision.”

(“They will be thinking about how to pay for the lawyer’s fees and the cost of travelling to and from the court. Our justice system does not encourage victims to pursue a case because the system is very slow, and it takes a long time to come up with a decision.”)

Where the PNP can intervene, it does so as best as it could. WCPC chief Nebran said that the PNP had intensified trainings and specialized courses to constantly improve how authorities dealt with women and children victims of abuse. These trainings complement the information awareness campaigns that they conduct in public.

But authorities can only do so much. Ultimately, it still boils down to the rape victim’s willingness to come forward.

“Hindi namin sila matutulungan kung tatahimik lang sila,” WCPC chief Nebran said. —NB/JST, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular