'Daang matuwid' or 'maganda?' Road to elections still crooked and ugly

Crime in politics? Politics in crime?

Last of two parts

In the last elections, President Benigno Simeon C. Aquino III summoned voters to support his allies and associates who would supposedly help fulfill his epic “Daang Matuwid” project. Not to be outdone, Vice President Jejomar C. Binay and his opposition United Nationalist Alliance (UNA), coined their own shibboleth to distinguish their candidates from Team PNoy: “Daang Maganda.”

By all indications, however, “Daang Matuwid” and “Daang Maganda” were nothing but brave yet empty messages lost in translation to both administration and opposition political parties. Indeed, both coalitions even became vehicles by which crime burrowed its way into politics, and politics into crime, in the May 2013 elections.

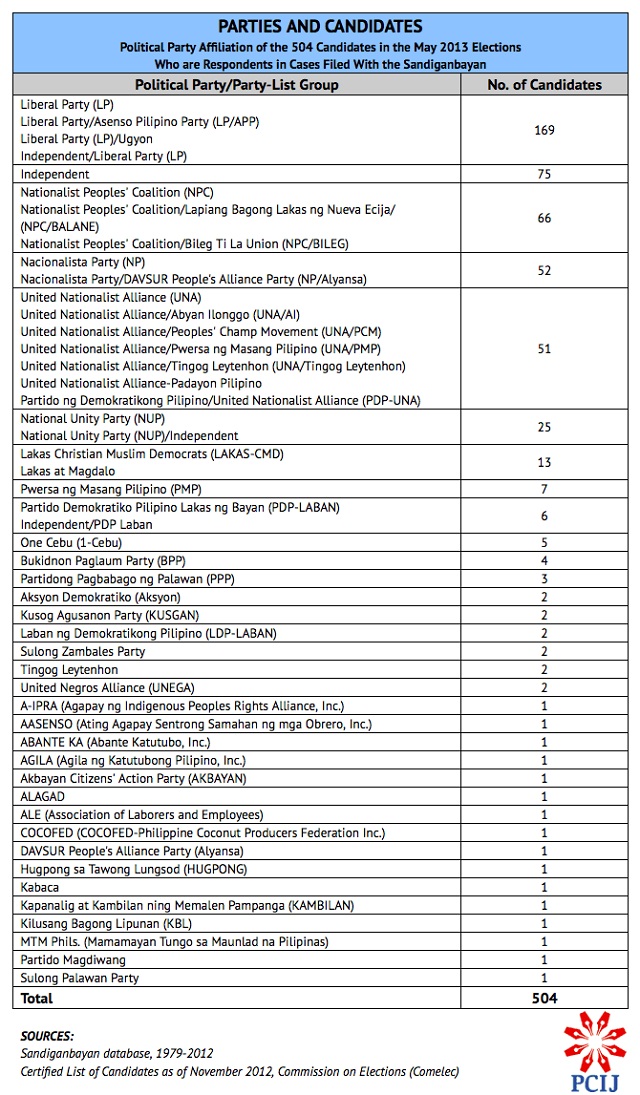

Political parties fielded at least 504 candidates with graft and crime cases before the Sandiganbayan anti-graft court. Of these candidates, 256 were elected or re-elected.

Commission on Elections Commissioner Christian Robert S. Lim says that the political parties should have performed leadership and oversight duties to make sure that their candidates would be the most deserving of the voters’ trust.

Unfortunately, of the 504 candidates with cases, no less than Aquino’s Liberal Party (LP) fielded 169, and Binay’s UNA, 51.

About one in four out of over 45,000 candidates ran under the LP banner in the May 2013 elections.

LP harbored under its wings the biggest number of candidates who had been convicted of a crime: seven. LP also fielded four candidates who had been sued for alleged robbery, and one for alleged murder.

UNA, meanwhile, embraced three convicted candidates – all of whom won eventually -- and fielded others who had been sued for estafa and murder.

Six other elected UNA candidates are facing graft charges: mayor-elect Oscar G. Malapitan of Caloocan City; mayor-elect Isidro T. Cabaddu of Camalaniugan, Cagayan; mayor-elect Neptali P. Salcedo of Sara, Iloilo; vice mayor-elect Pedro E. Budiongan Jr. of Carmen, Bohol; vice mayor-elect Arthur J. Golez of Silay City, Negros Occidental; and vice mayor-elect Rolando C. Javier of Plaridel, Bulacan.

NPC, NP, Lakas, too

Many more LP and UNA partisans are facing various charges for violation of anti-graft laws, but it takes some doing to figure out which party is affiliated with which coalition.

For example, a breakaway faction of Lakas-CMD has reinvented itself under the name National Unity Party (NUP), whose leaders include re-elected Quezon City Rep. Feliciano Belmonte Jr. The NUP fielded 25 candidates with cases before the Sandiganbayan, while Lakas-CMD had 13.

Meanwhile, for apparent political expediency, some members of the Nationalist People’s Coalition (NPC), Nacionalista Party (NP), Partido Demokratiko Pilipino-Lakas ng Bayan (PDP-Laban), and Lakas-Christian Muslim Democrats (Lakas-CMD) ran with support from the Team PNoy/LP coalition, and the others, under the banner of the UNA coalition.

NPC fielded two winning candidates who had been convicted, while PDP-Laban, Lakas-CMD, and the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) had one convicted candidate each who won in the last balloting.

The Nacionalista Party of former senator Manuel B. Villar Jr. and his senator-elect wife, Cynthia A. Villar had 31 election winners with cases before the anti-graft court. They include re-elected Ilocos Norte Rep. Rodolfo C. Fariñas; mayor-elect Marilyn B. Marquez of Dinalungan, Aurora; mayor-elect Enrico M. Alvarez of Noveleta, Cavite; mayor-elect Calixto R. Cataquiz of San Pedro, Laguna; vice mayor-elect Washington M. Taguinod of Penablanca, Cagayan; and vice mayor-elect Freddie I. Chu of Kabasalan, Zamboanga Sibugay.

Guilty verdict

One of the three convicted UNA candidates, Eugene Lariza Alzate, was elected provincial board member of the second district of Sarangani. On August 22, 2012, the Sandiganbayan found him guilty of malversation charges while serving as board member. The Court of Appeals had upheld his conviction and dismissal from public office.

The case of Melchor G. Maderazo, councilor-elect of Caibiran, Biliran, is also most incredulous. LP fielded him as a candidate although the Supreme Court had affirmed his conviction in a threat and coercion case as early as Sept. 26, 2006.

Know Your Candidate rule

That so many candidates with cases at the Sandiganbayan managed to worm their way into the elections, and back into power, is a problem with multiple roots.

A KYC (know your candidate) policy for political parties should already be a given, just as banks and credit agencies have a KYC (know your client) policy when evaluating applications for loan or credit.

Says Comelec’s Lim: “If you are talking about malversation, unless it was brought to the national consciousness, the case of the candidate has no effect on the party. But it should be the duty of the party to make sure their candidates are qualified.”

But because political parties have chosen to look the other way, or ignored the fact of their candidates having graft and criminal cases, Lim notes, the task of exposing this dark side of elections and politics has been left to the rival candidates of those with cases. Or as he puts it, “The rival candidate is now your lookout.”

The task of figuring out just who the candidates are become more complicated in cases where they are running unopposed. As Lim points out, “Even if (he or she is) not qualified… (and) all his or her qualifications are falsified and no one is complaining, that candidate will have no problems going through.”

“In fact,” says the commissioner, “we have had candidates that we didn’t know until it was too late that the court decision was already final, there was already a conviction. But it’s usually the rival who files and brings out the document… The courts are not mandated to give us records.”

Laws in discord

Another big obstacle to ferreting out candidates accused of grave offenses from joining elections is the law itself.

For instance, the Omnibus Election Code of the Philippines (Batas Pambansa No. 881, enacted Dec. 3, 1985) in Section 12 states the grounds for disqualifying any person from running for public office thus: “Any person who has been declared by competent authority insane or incompetent, or has been sentenced by final judgment for subversion, insurrection, rebellion or for any offense for which he has been sentenced to a penalty of more than 18 months or for a crime involving moral turpitude, shall be disqualified to be a candidate and to hold any office, unless he has been given plenary pardon or granted amnesty.”

But the Code specifies as well that “these disqualifications to be a candidate… shall be deemed removed upon the declaration by competent authority that said insanity or incompetence had been removed or after the expiration of a period of five years from his service of sentence, unless within the same period again becomes disqualified.”

A second law, the Local Government Code of 1991 (Republic Act No.7160, enacted on Oct. 10, 1991) in Section 40 enumerates these grounds for disqualification of a candidate in elections:

-

“Those sentenced by final judgment for an offense involving moral turpitude or for an offense punishable by one (1) year or more of imprisonment, within two (2) years after serving sentence;

-

“Those removed from office as a result of an administrative case;

-

“Those convicted by final judgment for violating the oath of allegiance to the Republic;

-

“Those with dual citizenship;

-

“Fugitives from justice in criminal or non-political cases here or abroad;

-

“Permanent residents in a foreign country or those who have acquired the right to reside abroad and continue to avail (themselves) of the same right after the effectivity of this Code; and

-

“The insane or feeble-minded.”

Perpetual, temporary

Yet a third law, The Revised Penal Code of the Philippines enumerates various levels of penalties for various crimes, including “perpetual or temporary special/absolute disqualification” from public office.

Articles 30 to 33 specify the effects of having such penalties:

“Perpetual or temporary absolute disqualification”

-

“The deprivation of the public offices and employments which the offender may have held even if conferred by popular election;

-

“The deprivation of the right to vote in any election for any popular office or to be elected to such office;

-

“The disqualification for the offices or public employments and for the exercise of any of the rights mentioned;

-

“In case of temporary disqualification, such disqualification as is comprised in paragraphs 2 and 3 of this article shall last during the term of the sentence;

-

“The loss of all rights to retirement pay or other pension for any office formerly held.”

“Perpetual or temporary special disqualification”

-

“The deprivation of the office, employment, profession or calling affected;

-

“The disqualification for holding similar offices or employments either perpetually or during the term of the sentence according to the extent of such disqualification.

The penalties cover the following cases: direct bribery, fraud, malversation, conniving with a prisoner evading, maltreatment of prisoners, and usurpation of legislative power, among others.

Duration of disqualification

A big contradiction exists, however, between the Local Government Code and the Omnibus Election Code on the matter of how long the disqualification status of a candidate should last.

The Local Government Code allows the disqualification status of candidates who are running for local government positions, up to the level of governor, convicted of crime to lapse two years after he or she had served his/her sentence. For those running for national elective positions, the period is five years.

In the Omnibus Election Code, however, a five-year disqualification period applies to all candidates.

According to Lim, in cases where there is a contradiction, the Local Government Code will apply because it was enacted after the Omnibus Election Code. Thus, for candidates for local government positions, the Local Government Code is seen to be the applicable law while the Omnibus Election Code serves as the law in reference to candidates for president, vice president, senators, and district and party-list representatives.

Presumption of innocence

And then there’s the third big obstacle to settling the unsettled graft and criminal cases of candidates: the exceedingly slow justice system itself.

Moving to disqualify candidates is a task that would test anyone’s patience and resources.

It would be best, according to Commissioner Lim, to have these candidates expunged from the picture before their proclamation as election winners. Voters and interested parties may take two paths to achieve this: First, by filing a petition to deny due course or to cancel the candidate’s Certificate of Candidacy (COC); and second, by filing a petition for disqualification to run or to hold any public office.

Jose Manuel Diokno, dean of De La Salle University’s College of Law, cites two important principles that must be weighed, though: “presumption of innocence” and “final judgment” on cases.

Diokno says that every person charged with a crime is entitled to presumption of innocence until proven guilty by “final judgment,” a protection accorded all citizens by the Constitution’s Bill of Rights.

This means that any criminal or administrative charges against a candidate must not cause him to relinquish his or her right to run for public office, and most especially, his or her right to vote.

“Final judgment” may be secured two ways. The first is when a person is convicted by a lower court, did not file an appeal with a higher court, and went on to serve his or her sentence. The second is when a person is convicted by a lower court, filed an appeal, and a higher court or the Supreme Court itself has ruled to affirm his/her conviction.

Final judgment

Diokno, however, concedes that securing “final judgment” in cases where politicians with power and position stand accused of crimes, is often marred by extended delays.

“The long drawn-out process has become a problem,” he says. “The appeals process alone is so slow that it takes six to 10 years.” Thus, candidates convicted of crime by the lower courts and the Sandiganbayan have been allowed free pass to run on and on in elections.

To set things in order, Diokno says, the courts could give priority to cases on appeal, especially those involving candidates who had been convicted by the lower courts. He comments, “You just can’t have appeals still unresolved after five, 10, or more years.”

Given the current circumstances, Diokno says that voters must be vigilant when assessing the record and qualifications to public office of candidates with cases before the courts. He notes, “Usually, if you have a lot of cases then there’s also a good chance that your record might be questionable.”

Having a string of graft and criminal cases could define a candidate’s credibility at the very least, even as in some cases, the charges are filed by rival candidates for political reasons.

Still and all, Diokno says, “the most important is integrity and honesty.” – With research and reporting by Rowena F. Caronan and Malou Mangahas, PCIJ

Editor's note: This article has been edited for brevity. For the full report, please click here.

Read Part 1 here