ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Topstories

News

How a workers' strike became the Luisita Massacre

By STEPHANIE DYCHIU

Third of five parts on the history of Hacienda Luisita, a burning issue facing frontrunner Sen. Noynoy Aquino's campaign for the presidency. Part four is here. “It is an illegal strike, no strike vote was called," then-Tarlac Congressman Benigno “Noynoy" Aquino III said in a speech at the House of Representatives to defend the dispersal of strikers at his family’s plantation, the Philippine Daily Inquirer reported on November 17, 2004. The day before, the dispersal at Hacienda Luisita left at least seven people dead and 121 injured, 32 from gunshot wounds. In his speech, Aquino condemned the violence but defended the dispersal, saying the police and soldiers were “subjected to sniper fire coming from an adjacent barangay." Luisita, 'the symbol of the failure of EDSA' Five days later, Aquino was flogged by Inquirer columnist Conrado De Quiros.

Part 1: Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future The issues surrounding Hacienda Luisita are being seen as the first real test of character of presidential hopeful Noynoy Cojuangco Aquino, whose family has owned the land since 1958. Our research shows that the problem began when government lenders obliged the Cojuangcos to distribute the land to small farmers by 1967, a deadline that came and went.

Part 1: Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future The issues surrounding Hacienda Luisita are being seen as the first real test of character of presidential hopeful Noynoy Cojuangco Aquino, whose family has owned the land since 1958. Our research shows that the problem began when government lenders obliged the Cojuangcos to distribute the land to small farmers by 1967, a deadline that came and went.  Part 2: Cory’s land reform legacy to test Noynoy’s political will There is a haunting resemblance between Senator Aquino’s “Hindi Ka Nag-Iisa" music video and a real-life torchlit march of Hacienda Luisita’s workers days before the November 16, 2004 massacre. What could be worth all the blood that has been spilled?

Part 2: Cory’s land reform legacy to test Noynoy’s political will There is a haunting resemblance between Senator Aquino’s “Hindi Ka Nag-Iisa" music video and a real-life torchlit march of Hacienda Luisita’s workers days before the November 16, 2004 massacre. What could be worth all the blood that has been spilled?

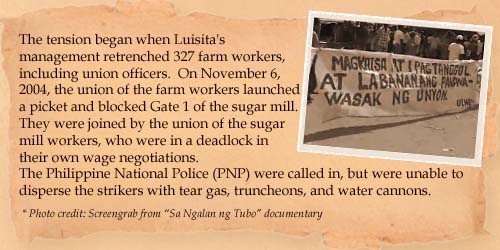

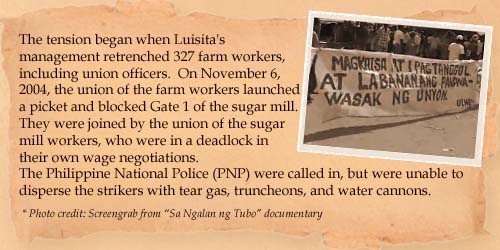

They were joined by the union of the sugar mill workers (Central Azucarera de Tarlac Labor Union or CATLU), who were in a deadlock in their own wage negotiations. The sugar mill workers blocked Gate 2 of the sugar mill. The Philippine National Police (PNP) were called in, but were unable to disperse the strikers with tear gas, truncheons, and water cannons. Almost all 5,000 members of ULWU and 700 members of CATLU joined the November 6 strike, while 80 CATLU members chose to continue working, according to a statement delivered under oath by Dr. Carol Pagaduan-Araullo of the Health Alliance for Democracy at the February 3, 2005 Senate hearing on the Luisita massacre. Araullo’s group conducted their own medical examination and investigation because of fears of a government whitewash. (Araullo is also the chairperson of Bagong Alyansang Makabayan or BAYAN.) The strike of the farm workers’ union (United Luisita Workers’ Union or ULWU) on November 6, 2004 at Gate 1 of the sugar mill was not covered by the assumption of jurisdiction of the Labor secretary. The case was with the National Labor Relations Commission, according to the statement of Dr. Carol Pagaduan-Araullo of the Health Alliance for Democracy at the February 3, 2005 Senate hearing on the Luisita massacre. Continue reading... Did Gloria help the Aquinos? On November 10, 2004, four days after the strike started, the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) declared an Assumption of Jurisdiction. Labor Secretary Patricia Sto. Tomas announced that quelling the strike was a matter of national interest because Luisita was one of the country’s major sugar producers. The Assumption of Jurisdiction legally cleared the way to use government troops to stop the strike. The picketers were ordered to vacate within five days, or else be removed by force. Under normal conditions, the Labor Code protects the right of workers—even those who have been retrenched—to demonstrate against their employers. Police are not allowed to break up non-violent pickets, and the military cannot be used like a security agency to solve the problems of private businessmen. The Assumption of Jurisdiction, however, is like a declaration of Martial Law in a labor dispute. It strips workers of their right to demonstrate, and authorizes the use of law enforcement agencies. The Assumption of Jurisdiction is allowed by the Labor Code only if a strike jeopardizes national interest. The strikers in Luisita grumbled that management was able to get the DOLE to declare an Assumption of Jurisdiction because it had a direct line to Malacañang through former President Cory Cojuangco Aquino, whose children Kris and Noynoy supported President Gloria Arroyo in the presidential elections just six months before (May 2004). The Aquinos and their followers also helped put Arroyo in power after ousting President Joseph Estrada in 2001.

The strike of the farm workers’ union (United Luisita Workers’ Union or ULWU) on November 6, 2004 at Gate 1 of the sugar mill was not covered by the assumption of jurisdiction of the Labor secretary. The case was with the National Labor Relations Commission, according to the statement of Dr. Carol Pagaduan-Araullo of the Health Alliance for Democracy at the February 3, 2005 Senate hearing on the Luisita massacre. Continue reading... Did Gloria help the Aquinos? On November 10, 2004, four days after the strike started, the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) declared an Assumption of Jurisdiction. Labor Secretary Patricia Sto. Tomas announced that quelling the strike was a matter of national interest because Luisita was one of the country’s major sugar producers. The Assumption of Jurisdiction legally cleared the way to use government troops to stop the strike. The picketers were ordered to vacate within five days, or else be removed by force. Under normal conditions, the Labor Code protects the right of workers—even those who have been retrenched—to demonstrate against their employers. Police are not allowed to break up non-violent pickets, and the military cannot be used like a security agency to solve the problems of private businessmen. The Assumption of Jurisdiction, however, is like a declaration of Martial Law in a labor dispute. It strips workers of their right to demonstrate, and authorizes the use of law enforcement agencies. The Assumption of Jurisdiction is allowed by the Labor Code only if a strike jeopardizes national interest. The strikers in Luisita grumbled that management was able to get the DOLE to declare an Assumption of Jurisdiction because it had a direct line to Malacañang through former President Cory Cojuangco Aquino, whose children Kris and Noynoy supported President Gloria Arroyo in the presidential elections just six months before (May 2004). The Aquinos and their followers also helped put Arroyo in power after ousting President Joseph Estrada in 2001.  Labor Secretary Patricia Sto. Tomas declared an Assumption of Jurisdiction over the Luisita dispute on November 10, 2004. Sto. Tomas said quelling the strike was a matter of national interest because Luisita was one of the country’s major sugar producers. This paved the way for sending government troops to stop the strike. Continue reading... The strikers stayed put, determined to make management come out and negotiate. EDSA meets Mendiola To protect themselves from the forthcoming forcible removal, the workers called on the people in the barrios around Luisita to form a human barrier at the picket line, says Lito Bais, current acting president of ULWU. In an eerie EDSA-meets-Mendiola spectacle, the villagers came, including priests, barangay officials, and children whose families sympathized with the workers. Concerned groups from out of town also sent contingents to help protect the strikers. On November 15, 2004, the PNP returned as promised with reinforcements. According to Araullo’s report to the Senate, around 400 policemen tried to disperse about 4,000 protesters. CATLU president Ric Ramos was hit and collapsed from a large head wound, but the police were still unable to break the picket.

Labor Secretary Patricia Sto. Tomas declared an Assumption of Jurisdiction over the Luisita dispute on November 10, 2004. Sto. Tomas said quelling the strike was a matter of national interest because Luisita was one of the country’s major sugar producers. This paved the way for sending government troops to stop the strike. Continue reading... The strikers stayed put, determined to make management come out and negotiate. EDSA meets Mendiola To protect themselves from the forthcoming forcible removal, the workers called on the people in the barrios around Luisita to form a human barrier at the picket line, says Lito Bais, current acting president of ULWU. In an eerie EDSA-meets-Mendiola spectacle, the villagers came, including priests, barangay officials, and children whose families sympathized with the workers. Concerned groups from out of town also sent contingents to help protect the strikers. On November 15, 2004, the PNP returned as promised with reinforcements. According to Araullo’s report to the Senate, around 400 policemen tried to disperse about 4,000 protesters. CATLU president Ric Ramos was hit and collapsed from a large head wound, but the police were still unable to break the picket.

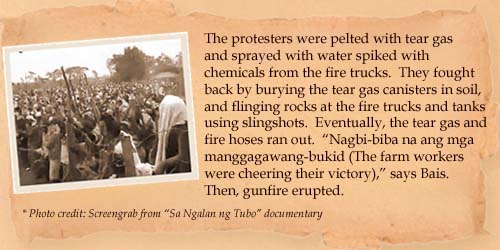

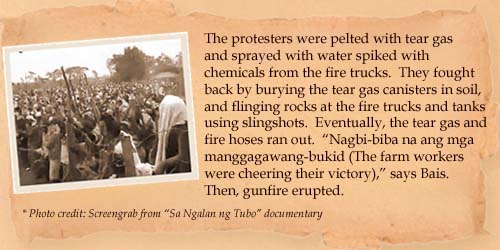

The trip to the Cojuangco house Sometime in the afternoon of November 15, according to Bais, the union leaders were told to go to the house of Jose “Peping" Cojuangco, Jr. in Makati to talk. The negotiations were to be mediated by party-list congressman Satur Ocampo. Ocampo had gone to Luisita along with fellow Bayan Muna party-list congressman Teddy Casiño to aribitrate with the police. The next morning, November 16, 2004, the union officers left Tarlac for Makati. “Kinabahan na ang mga opisyales namin, pagdating nila sa Makati, na parang may mangyayari dito (Our union officers got worried as soon as they reached Makati. They had a feeling something was going to happen here)," says Bais, who was not yet acting president of ULWU at that time, and had stayed behind. “Parang inalis lang sila dito (It was like they were just lured away from here)." At the Cojuangco house in Makati, the CATLU officers were told negotiations could only happen if the strike was stopped first. The ULWU officers were not allowed in because they were considered retrenched and no longer authorized to negotiate for the farm workers. While the union officers were in Makati, the military rolled into Luisita. The union officers now believe the meeting in Makati was just a ruse to lure them away so the military could move into the hacienda. 2 tanks, 700 police, 17 trucks of soldiers When the union officers returned to the picket line around 3:00 pm after their fruitless trip to Makati, the place looked like a war was about to begin. Near Gate 1 of the sugar mill were “700 policemen, 17 truckloads of soldiers in full battle gear, 2 tanks equipped with heavy weapons, a payloader, 4 fire trucks with water cannons, and snipers positioned in at least 5 strategic places", according to Araullo’s report to the Senate. One of the tanks and the payloader rammed through the sugar mill gate that management had previously locked. The protesters were pelted with tear gas and sprayed with water spiked with chemicals from the fire trucks. They fought back by burying the tear gas canisters in soil, and flinging rocks at the fire trucks and tanks using slingshots. Eventually, the tear gas and fire hoses ran out. “Nagbi-biba na ang mga manggagawang-bukid (The farm workers were cheering their victory)," says Bais. The strikers surged through the gate, waving sticks and throwing rocks at the tank. Then, gunfire erupted. 1,000 rounds of ammunition used The first spray of bullets lasted for almost a full minute, as men, women, and children ran for their lives. This was followed by a series of rapid spurts. According to Araullo’s statement, the presidents of the two unions narrowly missed being shot by snipers while running to get behind some sugarcane trucks. Other protesters were beaten and dragged into army trucks and placed under arrest, regardless of gender or age. Doctors who later autopsied the dead and examined the wounded said the victims were running, crouching, or lying down when they were shot. At the December 1, 2004 Senate hearing on the massacre, videos of the bloody dispersal caught by the media were shown. It was revealed that an astounding 1,000 rounds of ammunition were used by the military and police during the shooting.

Jhaivie was the youngest of the victims who died. He worked part-time at Central Azucarera de Tarlac, cleaning sugarcane every Monday, to earn money after he stopped going to college when his father died six months before the massacre. His mother said Jhaivie was a homebody, but he went to support the strike because almost all the children in his barangay were children of farm workers in Hacienda Luisita, and he understood what they were fighting for. Continue reading... Noynoy defends dispersal On November 17, 2004, the day after the massacre, the Philippine Daily Inquirer reported: “At the House of Representatives, Deputy Speaker Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino III (LP, Tarlac) , only son of the former President, defended the dispersal of the protesters … Aquino said that elements of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and Philippine National Police who dispersed the workers were ‘subjected to sniper fire coming from an adjacent barangay’… Aquino noted that 400 of the 736 workers in question had decided to return to work." In the same report, Aquino’s uncle, former Tarlac Rep. Jose “Peping" Cojuangco, Jr., said he received a copy of a press statement from ULWU saying it was not the group behind the picket. Ronaldo Alcantara of ULWU said in the statement that a small group of retrenched workers led by Rene Galang, a former official of ULWU, and Ric Ramos, president of CATLU, were behind the incidents at the hacienda. The next day, November 18, 2004, the Philippine Star reported: “Tarlac Rep. Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino III said yesterday there was strong evidence that the clash was triggered by gunfire coming from the ranks of the strikers. He said when the police tried to break the barricade using an armored personnel carrier, they were fired upon by strikers. He cited there were at least eight bullet marks on the APC. Aquino also urged his militant colleagues in Congress against conducting fact-finding missions at the Hacienda, which he said could further ‘inflame the situation.’ Aquino earlier claimed that outsiders instigated the rioting." PNP report echoes Noynoy defense Months later, the PNP submitted its own report to the Senate dated January 24, 2005. The PNP’s account was similar to the statements Aquino gave right after the massacre.

Jhaivie was the youngest of the victims who died. He worked part-time at Central Azucarera de Tarlac, cleaning sugarcane every Monday, to earn money after he stopped going to college when his father died six months before the massacre. His mother said Jhaivie was a homebody, but he went to support the strike because almost all the children in his barangay were children of farm workers in Hacienda Luisita, and he understood what they were fighting for. Continue reading... Noynoy defends dispersal On November 17, 2004, the day after the massacre, the Philippine Daily Inquirer reported: “At the House of Representatives, Deputy Speaker Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino III (LP, Tarlac) , only son of the former President, defended the dispersal of the protesters … Aquino said that elements of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and Philippine National Police who dispersed the workers were ‘subjected to sniper fire coming from an adjacent barangay’… Aquino noted that 400 of the 736 workers in question had decided to return to work." In the same report, Aquino’s uncle, former Tarlac Rep. Jose “Peping" Cojuangco, Jr., said he received a copy of a press statement from ULWU saying it was not the group behind the picket. Ronaldo Alcantara of ULWU said in the statement that a small group of retrenched workers led by Rene Galang, a former official of ULWU, and Ric Ramos, president of CATLU, were behind the incidents at the hacienda. The next day, November 18, 2004, the Philippine Star reported: “Tarlac Rep. Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino III said yesterday there was strong evidence that the clash was triggered by gunfire coming from the ranks of the strikers. He said when the police tried to break the barricade using an armored personnel carrier, they were fired upon by strikers. He cited there were at least eight bullet marks on the APC. Aquino also urged his militant colleagues in Congress against conducting fact-finding missions at the Hacienda, which he said could further ‘inflame the situation.’ Aquino earlier claimed that outsiders instigated the rioting." PNP report echoes Noynoy defense Months later, the PNP submitted its own report to the Senate dated January 24, 2005. The PNP’s account was similar to the statements Aquino gave right after the massacre.  The final report of the Philippine National Police (PNP) on the November 16, 2004 Luisita massacre was submitted on January 24, 2005. It cleared the PNP of blame, and reported that: > The order to disperse the strikers was made only after the police saw that negotiations between the Department of Labor’s sheriff and the strike leaders had failed. > The PNP observed maximum tolerance and were simply helping the sheriff implement a return-to-work order. > The “initial burst of gunfire, single shots in succession, came from the ranks of the striking workers after they crossed the gate and invaded the CAT (Central Azucarera de Tarlac) compound". > Evidence gathered confirmed the presence and participation of the New People’s Army (NPA), but “the evidence will not suffice for their criminal prosecution". > The resistance put up by the strikers resulted in the death of seven strikers and wounding of 36 others. > 100 policemen and soldiers were injured. > 111 civilians were arrested and assorted guns and several bolos and knives were recovered from the scene. > The violence was orchestrated by individuals who were not members of the striking unions, and firearms and explosives were used to generate a more violent reaction from the government forces. >The slain workers were not residents of Tarlac or employees of Hacienda Luisita. Read “Who were the 7 who died in the Luisita massacre?" The PNP’s report was debunked point-by-point by the workers and the party-list group BAYAN, which had conducted its own fact-finding investigation. (Manila Times, December 8, 2005) In addition, the report said the PNP only went to Luisita on November 16, 2004 to assist the DOLE in implementing a return-to-work order. Maximum tolerance was observed, and the order to disperse was made only after the police saw that negotiations with the strike leaders had failed. Evidence gathered, according to the report, “confirms the presence and participation of the NPA (New People’s Army) in the strike." The report also said 100 policemen and soldiers were injured.

The final report of the Philippine National Police (PNP) on the November 16, 2004 Luisita massacre was submitted on January 24, 2005. It cleared the PNP of blame, and reported that: > The order to disperse the strikers was made only after the police saw that negotiations between the Department of Labor’s sheriff and the strike leaders had failed. > The PNP observed maximum tolerance and were simply helping the sheriff implement a return-to-work order. > The “initial burst of gunfire, single shots in succession, came from the ranks of the striking workers after they crossed the gate and invaded the CAT (Central Azucarera de Tarlac) compound". > Evidence gathered confirmed the presence and participation of the New People’s Army (NPA), but “the evidence will not suffice for their criminal prosecution". > The resistance put up by the strikers resulted in the death of seven strikers and wounding of 36 others. > 100 policemen and soldiers were injured. > 111 civilians were arrested and assorted guns and several bolos and knives were recovered from the scene. > The violence was orchestrated by individuals who were not members of the striking unions, and firearms and explosives were used to generate a more violent reaction from the government forces. >The slain workers were not residents of Tarlac or employees of Hacienda Luisita. Read “Who were the 7 who died in the Luisita massacre?" The PNP’s report was debunked point-by-point by the workers and the party-list group BAYAN, which had conducted its own fact-finding investigation. (Manila Times, December 8, 2005) In addition, the report said the PNP only went to Luisita on November 16, 2004 to assist the DOLE in implementing a return-to-work order. Maximum tolerance was observed, and the order to disperse was made only after the police saw that negotiations with the strike leaders had failed. Evidence gathered, according to the report, “confirms the presence and participation of the NPA (New People’s Army) in the strike." The report also said 100 policemen and soldiers were injured.

Noynoy and PNP statements refuted The statements of Aquino and the PNP were refuted by the strikers and the leftist political alliance BAYAN, which had conducted its own fact-finding mission. According to them, it was impossible for the sniper fire to have come from the ranks of the strikers because the shots emanated from inside the sugar mill compound, which only management, the military, and the police had access to until the gate that management had locked was rammed open by the military’s tank right before the firing started. Moreover, they said, it was highly unlikely that the shooting started from the strikers’ side because there were no casualties among the military and police, while there were 7 killed and 32 wounded by gunshots among the strikers. As for the bullets on the APC mentioned by Aquino, they said it did not make sense for the strikers to fire at a tank, which is bulletproof, but not shoot any of the 700 soldiers and policemen around. The bullets could have been planted. The group also said no negotiations with strike leaders could have taken place on the afternoon of November 16, 2004, as the PNP claimed, because the union officers had barely arrived from the Cojuangco house in Makati when dispersal operations escalated. In their sworn statements, the police officers in charge of the dispersal could not even give the names of the strike leaders they said they negotiated with before launching the assault. Misleading the media Furthermore, while the PNP linked the NPA to the strike, the PNP also said in their report that “evidence gathered against alleged members of the NPA will not suffice for their criminal prosecution", in effect negating their own claim. Meanwhile, Ronaldo Alcantara, the officer of ULWU who denied ULWU was behind the strike in the Inquirer report, was a lower-level former officer of the union who was used to mislead the media, according to current ULWU acting president Lito Bais. The president of ULWU registered at the Bureau of Labor Relations at the time of the strike was Rene Galang. Bais says management encouraged splinter factions in the union led by persons under their control. The PNP’s report did not say anything about the takeover of St. Martin de Porres Hospital that happened just before the dispersal was launched. The wake at the sugar mill Days after the massacre, five out of the seven dead bodies were brought by the farm workers and their sympathizers to the picket line near the gate of the sugar mill. How were they able to go near the gate when the military was still there standing guard? “Sabi namin, siguro naman, patay na ang dala natin, igagalang naman nila. Sila ang pumatay, e (We just said, maybe, since the people we were carrying were already dead, they would respect that. After all, they were the ones who killed them)," says Bais. The procession was led by a councilor from Tarlac City named Abel Ladera, who grew up in one of the barangays inside Hacienda Luisita. He became an engineer, and once worked inside the sugar mill. The workers relied on the presence of Ladera, an elected official, and some media men to keep management and the military at bay. As the coffins were being lowered and the barbed wire removed, the soldiers went inside the sugar mill so the mourners could prepare for the wake. Little did Ladera know that his sympathetic involvement with the strikers would put him in mortal danger. Union’s office destroyed After the massacre victims’ coffins were brought to the picket line, Bais says the union’s office was destroyed by soldiers. “Nung balikan namin ang opisina namin, wala na lahat. Ultimo ang computer na gamit namin, giba-giba na. Yung mga file, lahat, wala na kaming inabutan. (When we went back to our office, everything was gone. Even the computer we were using was totally destroyed. Our files, everything, we were not able to save anything)." The collection of pictures of the union’s past presidents since the workers’ struggle began was also destroyed, he adds. Hundreds of soldiers moved into Luisita’s different barangays. To justify the presence of the military, officials of the Northern Luzon Command (NOLCOM) presented a report to the media saying the workers’ strike at Hacienda Luisita was the “handiwork of the CPP-NPA (Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s Army) and a culmination of long months of instigation and propaganda work to get the workers to rise up in arms against the Cojuangcos." Asked for comment on this story, Sen. Noynoy Aquino’s spokesman Edwin Lacierda said, “Noynoy regrets the massacre but the mass action was infiltrated. It was started by infiltrators." After conducting hearings about the massacre and recording the testimonies of witnesses, the Senate Committee on Labor and Employment never issued a formal report.

Part 1: Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future The issues surrounding Hacienda Luisita are being seen as the first real test of character of presidential hopeful Noynoy Cojuangco Aquino, whose family has owned the land since 1958. Our research shows that the problem began when government lenders obliged the Cojuangcos to distribute the land to small farmers by 1967, a deadline that came and went.

Part 1: Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future The issues surrounding Hacienda Luisita are being seen as the first real test of character of presidential hopeful Noynoy Cojuangco Aquino, whose family has owned the land since 1958. Our research shows that the problem began when government lenders obliged the Cojuangcos to distribute the land to small farmers by 1967, a deadline that came and went.  Part 2: Cory’s land reform legacy to test Noynoy’s political will There is a haunting resemblance between Senator Aquino’s “Hindi Ka Nag-Iisa" music video and a real-life torchlit march of Hacienda Luisita’s workers days before the November 16, 2004 massacre. What could be worth all the blood that has been spilled? The answer lies in a contentious 30-year stock distribution scheme, a legacy from former President Aquino.

Part 2: Cory’s land reform legacy to test Noynoy’s political will There is a haunting resemblance between Senator Aquino’s “Hindi Ka Nag-Iisa" music video and a real-life torchlit march of Hacienda Luisita’s workers days before the November 16, 2004 massacre. What could be worth all the blood that has been spilled? The answer lies in a contentious 30-year stock distribution scheme, a legacy from former President Aquino.

Part 4: After Luisita massacre, more killings linked to protest After the massacre of 2004, eight more people who were either leaders or supporters of the Luisita strike were murdered in Tarlac. A GMANews.TV investigation reveals that a survivor of one shooting testified in 2005 that Sen. Noynoy Aquino had appealed to him about a "superhighway", which turned out to be the now controversial SCTex.

Part 4: After Luisita massacre, more killings linked to protest After the massacre of 2004, eight more people who were either leaders or supporters of the Luisita strike were murdered in Tarlac. A GMANews.TV investigation reveals that a survivor of one shooting testified in 2005 that Sen. Noynoy Aquino had appealed to him about a "superhighway", which turned out to be the now controversial SCTex.  Part 5: Win or lose, Noynoy has to face Luisita deadlock Since 2006, Hacienda Luisita and its farmer-beneficiaries have been locked in a stalemate after the Supreme Court temporarily stopped the implementation of a government order revoking the stock distribution option of the hacienda. In the fifth and last part of this series, presidential candidate Noynoy Aquino speaks on the range of Luisita-related issues that could hound his administraiton if he wins.

Part 5: Win or lose, Noynoy has to face Luisita deadlock Since 2006, Hacienda Luisita and its farmer-beneficiaries have been locked in a stalemate after the Supreme Court temporarily stopped the implementation of a government order revoking the stock distribution option of the hacienda. In the fifth and last part of this series, presidential candidate Noynoy Aquino speaks on the range of Luisita-related issues that could hound his administraiton if he wins.

They were joined by the union of the sugar mill workers (Central Azucarera de Tarlac Labor Union or CATLU), who were in a deadlock in their own wage negotiations. The sugar mill workers blocked Gate 2 of the sugar mill. The Philippine National Police (PNP) were called in, but were unable to disperse the strikers with tear gas, truncheons, and water cannons. Almost all 5,000 members of ULWU and 700 members of CATLU joined the November 6 strike, while 80 CATLU members chose to continue working, according to a statement delivered under oath by Dr. Carol Pagaduan-Araullo of the Health Alliance for Democracy at the February 3, 2005 Senate hearing on the Luisita massacre. Araullo’s group conducted their own medical examination and investigation because of fears of a government whitewash. (Araullo is also the chairperson of Bagong Alyansang Makabayan or BAYAN.)

Was it legal for the police to intervene in the strike?

Was Luisita’s sugar mill indispensable to the national interest?

Can retrenched union officers still represent the union under the Labor Code?

Article 212, Paragraph F of the Labor Code says that the definition of “Employee" includes “any individual whose work has ceased as a result of or in connection with any current labor dispute or because of any unfair labor practice if he has not obtained any other substantially equivalent and regular employment". Based on this provision, lawyers of the farm workers argued that management should still have recognized the retrenched union officers because they were still employees of the company under the law, since their retrenchment was still on appeal and they had not yet received separation pay. As employees, the lawyers said, the union officers had a right to self-organization and to fulfill their roles as leaders of the union.

Who were the 7 who died in the Luisita Massacre?

Summary of the PNP’s final report on the Luisita massacre

Noynoy on the Luisita massacre

“It is an illegal strike. No strike vote was called." (Philippine Daily Inquirer, November 17, 2004) “[The military and the police who dispersed the workers were] subjected to sniper fire coming from an adjacent barangay." (Philippine Daily Inquirer, November 17, 2004) The clash was triggered by gunfire coming from the ranks of the strikers. (Philippine Star, November 18, 2004) When police tried to break the barricade using an armored personnel carrier (APC), they were fired upon by the strikers. There were at least 8 bullet marks on the APC. (Philippine Star, November 18, 2004) Outsiders instigated the rioting. Among those injured were sympathizers who came from as far as the Visayas. (Philippine Star, November 18, 2004) The workers’ defense The Department of Labor declared an Assumption of Jurisdiction to quash the workers’ right to strike. The government issued this radical order because the Aquinos had a direct line to Malacañang (Noynoy and Kris Aquino supported President Gloria Arroyo in the 2004 elections). The sniper fire came from plainclothes men inside the sugar mill compound, which only Luisita management and the military/police could access until the military’s own tank rammed the sugar mill gate open shortly before firing started. If the strikers started the shooting, why were there no casualties among the military/police, but seven killed and 32 wounded by gunshots among the strikers? Why would the strikers fire bullets into an APC, which is resistant to bullets, but not shoot any of the 700 military/police around? The bullets on the APC could have been planted by the military/police. The injured who came from the Visayas were sacadas (seasonal sugarcane cutters) from Negros who were hired by the Cojuangcos, but sympathized with the strikers. TEDDY BENIGNO’S TAKE The late journalist Teodoro “Teddy" Benigno was a long-time friend of Ninoy and Cory Aquino. He served as Cory Aquino’s Press Secretary from 1986 to 1989. On November 19, 2004, Teddy Benigno wrote about the Luisita massacre in his column in the Philippine Star: “I would have wished that Ninoy’s son, Rep. Benigno (Noynoy) Aquino and brother-in-law Jose (Peping) Cojuangco just kept quiet. As it was they sort of blamed the dispersal and massacre on trouble-making outsiders—agents provocateurs—who had nothing to do with Luisita. Noynoy, you’re not Ninoy and you should have kept to yourself. Ditto for Peping. Those were self-serving statements and you knew it."

More Videos

Most Popular