TAMING THE MARKET

In response to the mounting public clamor for lower prices of life-saving drugs, the government finally stepped in to tame the unregulated drug market. Last July, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo issued Executive Order 821 to slash the prices essential medicines in half. The move came more than a year after Mrs. Arroyo signed into law Republic Act 9502 or the Universally Accessible Cheaper Medicines Act of 2008. However, the EO only covers five essential drugs: the anti-hypertensive Amlodipine, anti-cholesterol Atorvastatin; anti-infection Azithromycin, and anti-cancer Cytarabine and Doxorubicin. Sixteen other medicines were left to the voluntary compliance of companies.

CONTINUE READING… In the battle to slash the prices of medicines, the Arroyo administration seems to have won the first round, but the drug industry is proving to be a tough adversary. Several drug stores and hospital pharmacies have failed to comply with price cuts imposed last month, prompting the Department of Health (DOH) to warn erring establishments of fines or closure. The problem is nothing new. Making drugs accessible to the poor has been the battle cry of the government since then President Corazon Aquino came up with a national drug policy that resulted in the 1988 Generics Act, supposedly Asia’s first powerful drug price reduction law. But the battle cry has since turned into a broken record. More than 20 years after the generics law was implemented, the DOH found that with a measly four percent share, cheaper generic products have failed to corner a sizeable market. “There are significant problems in the access to medicines for the poor," the DOH reported in its

2005-2010 National Objectives for Health, which provides the road map for the country’s health sector. “The pharmaceutical market is dominated by expensive branded medicines, making drug prices in the Philippines among the highest in Asia," the report said. The DOH’s findings are similar to those of the World Health Organization (WHO), which included the Philippines in the list of countries where less than 30 percent of the population has regular access to essential medicines. Drug prices in the Philippines are 34 to 184 times higher than the international reference prices, according to the 2006 WHO Health Action International survey. For instance, a 500-milligram tablet of pain-reliever Ponstan costs P21.82 in the Philippines. But in India, the same brand of medicine with the same dosage only costs P2.61. Meanwhile, a 100-microgram inhaler of the salbutamol-based asthma medicine Ventolin costs P315 in the Philippines, but only P123.31 in India.

(See: WHO Western Pacific Region: Essential Drugs and Medicines Policy, Issue No. VII, 2007) The WHO also found out that due to the high prices of drugs, a Filipino government worker taking Ranitidine for a month's treatment of ulcer has to spend 8.5 days of his income for originator drugs, which are manufactured by companies holding the patent for that medicine. Meanwhile, a worker battling depression through an originator brand of fluoxetine will have to spend wages equivalent to 32.8 days for a month's treatment, according to the survey.

Larger than many nations Both the government and its critics agree that trade monopoly is the reason behind the exorbitant prices of drugs in the country. “There’s failure of competition," says DOH Undersecretary Alex Padilla, who has been with the department for the last eight years. “The drug industry is raking super-profit from the pockets of the poor," adds Dr. Darby Santiago, chairman of the Health Alliance for Democracy, a non-government organization of medical practitioners that is critical of the government’s health policies. Major players in the drug industry claim otherwise, saying the 50-percent cut in the prices of medicines will have a negative impact on their operations and even force them to lay off workers. “It looks like it’s hitting the big multinational companies, but the most affected are actually the local companies," Oscar Aragon of the Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Association of the Philippines (PHAP) said.

(See: Price cuts on drugs could lead to retrenchment) Private hospitals claim they are hurting, too. On September 15, the Private Hospitals Association of the Philippines said its members had increased the prices of their services after the government imposed the price cuts. “We are affected. Where are we going to get the money to pay salaries for our nurses, our pharmacists?" said Dr. Rustico Jimenez, the president of the group. But the statistics tell another story.

Sixteen of the top 20 drug companies in the Philippines are multinational firms with combined sales of P58.23 billion in 2007, nearly eight times more than the Philippines’ P7.39 billion GDP in 2008. The companies are Glaxo Smithkline, Pfizer, Wyeth, Sanofi-Aventis, Abbott, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche, Johnson and Johnson, Boeringher Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squib, Bayer, Schering Plough, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Servier, and Merck Inc. Their sales represent about 82 percent of the total volume sales of foreign pharmaceutical firms in the country, according to data from the

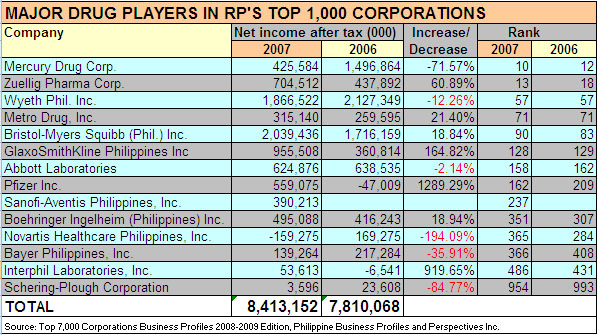

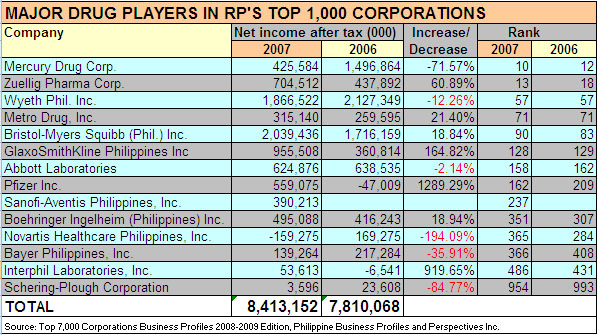

PHAP. The 16 companies' average compound annual growth rate of 8.5 percent in 2007 is higher than the Philippines' real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 7.3 percent in the same year. At least 10 of the multinational drug firms were among the Philippines’ top 1,000 corporations in 2007, with a total net income of P6.91 billion. Other major players in the Philippine drug industry that package, distribute, and sell drugs -- Zuellig Pharma Corp., Interphil Laboratories, Inc., Metro Drug Inc. and Mercury Drug Corp. -- are also in the list and had a combined profit of P1.49 billion in 2007. (

See Table) In 2008, industry data from the international firm IMS Health showed that the global drug industry generated sales of $733 billion (P35.18 trillion), about 20 times more than the $29.78 billion (P1.22 trillion) national budget of the Philippines for the same year. With the drug industry “economically larger than many nations," governments find it difficult to regulate their quest for profit at the expense of millions of poor people who cannot afford essential drugs, according to the advocates’ group Consumers International.

(See: Drugs, Doctors and Dinners: How drug companies influence health in the developing world) Market failure In a paper written for the April 2008 Health Policy Notes of the DOH, Dr. Joseph Lachica identified market failure as one of the stumbling blocks to access to essential medicines in the country. This happens when businesses that operate without much government intervention are given a free hand to set prices that are higher than those in competitive markets. Lachica says that on the supply side, “the lack of competition at various levels of the industry account for high drug prices and limited distribution." His analysis of the structure of the industry reveals that only five sectors control the manufacturing, distribution, and retail of pharmaceutical products in the Philippines. At the manufacturing level, foreign-owned companies that have exclusive rights to produce and sell patented drugs for at least 20 years control the industry. Lachica estimates that the profit share of the exporting company accounts for half of the price of the imported drug products upon reaching the Philippines. Next are toll manufacturers, or firms that have specialized equipment to further process or package drug products. Eighty percent of toll manufacturing in the Philippines is done by Interphil Laboratories, which is into the repacking and compounding market, according to Lachica.  Click the diagram to enlarge On the third level are the drug distributors that manufacturers rely on to handle their logistical needs. Lachica says 80 percent of drugs sold in the market are distributed by Zuellig Pharma Inc, which is the majority stockholder of Interphil.

Click the diagram to enlarge On the third level are the drug distributors that manufacturers rely on to handle their logistical needs. Lachica says 80 percent of drugs sold in the market are distributed by Zuellig Pharma Inc, which is the majority stockholder of Interphil. Doctors and the drug industry

There is no comprehensive study about the influence of big drug companies on advertising and the prescription behavior of physicians in the Philippines. But in the 2007 study “Drugs, Doctors, and Dinners," the advocacy group Consumers International claims that in many developing countries, doctors are the “main targets" for the promotional activities of drug firms. “With the power to prescribe and a high status in society, their opinion of a drug very often determines its sales and success. It is therefore not surprising that the majority of marketing spend by industry leaders goes towards direct-to-doctor promotion," the CI says in its study. Among the promotional tactics employed by drug firms is the practice of giving gifts to doctors, which range from small items such as gifts, pens, and notebooks to expensive foreign holidays, television sets, air conditioners, and even jewelry. According to DOH Undersecretary Alex Padilla, many Filipino doctors influenced by strong pharmaceutical lobby help maintain the “monopolistic" structure of the drug industry. "Doctors still prescribe branded medicines and they cannot be punished for that because there's a loophole in the law," Padilla says. The 1988 Generics Law allows doctors to write the generic name along with the branded name of the medicine on the prescription list. Padilla said the generics law has “failed" to weaken the dominance of branded medicines in the market. -

- ARCS, GMANews.TV In 2006, it was reported that holding company Khatibi had acquired Zuellig's 31.11 percent share from Interphil. But Khatibi, it turned out, was no stranger to Zuellig. The company, incorporated in the British Virgin Islands, was organized by Zuellig to hold the Class B shares of Interphil. On the fourth tier are retailers such as Mercury Drug, Inc. which accounts for almost 75 percent of the sales volume in the country. The rest of the medicines are sold in drug stores inside public or private hospitals. Lachica says monopoly pricing also exists in private hospitals where “outside purchases of drugs are discouraged, if not totally prohibited." At the bottom of the structure are physicians who virtually act as the frontline sales force of drug companies when they prescribe medicines to consumers. Dr. Henrietta Teresa Dela Cruz, assistant professor at the Ateneo de Manila University's Department of Biology, says that based on industry estimates, 40 to 60 percent of the actual chemical drug costs can go into advertising and retailing of drug products. University of the Philippines professor Orville Solon, director of the DOH-Philippine Institute for Development Studies project on health care financing reform, says this market structure shows that there are "interlocking interests" between drug manufacturers and distributors. This set-up “creates greater potential for vertical control over the industry," according to Solon. The structure will not change, according to Sonny Africa of the research group Ibon Foundation, as long as the government allows foreign companies to dominate the largely unregulated drug market. “Prices of drugs can be made affordable if the local industry can manufacture its own products, and this is possible if the industry puts to an end the transnational and multinational firm's monopoly over drug manufacturing and distribution," Africa says. While importation of drugs may be necessary, this should only be done to complement an existing local raw materials extraction and manufacturing, according to Africa. “With an independent, self-reliant drug manufacturing capability and a secure trading environment, the public can have access to affordable drugs. With all these in place, the country will have a capacity to build a national industry that is responsive to the health needs of the people," Africa says. For now, drugstores and medicine companies are not about to give up each other’s share of the profit pie. Several hospitals have agreed to sell essential drugs at 50 percent off the price only after getting an assurance from pharmaceutical firms they will pay the difference through rebates. - GMANews.TV

Sixteen of the top 20 drug companies in the Philippines are multinational firms with combined sales of P58.23 billion in 2007, nearly eight times more than the Philippines’ P7.39 billion GDP in 2008. The companies are Glaxo Smithkline, Pfizer, Wyeth, Sanofi-Aventis, Abbott, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche, Johnson and Johnson, Boeringher Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squib, Bayer, Schering Plough, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Servier, and Merck Inc. Their sales represent about 82 percent of the total volume sales of foreign pharmaceutical firms in the country, according to data from the PHAP. The 16 companies' average compound annual growth rate of 8.5 percent in 2007 is higher than the Philippines' real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 7.3 percent in the same year. At least 10 of the multinational drug firms were among the Philippines’ top 1,000 corporations in 2007, with a total net income of P6.91 billion. Other major players in the Philippine drug industry that package, distribute, and sell drugs -- Zuellig Pharma Corp., Interphil Laboratories, Inc., Metro Drug Inc. and Mercury Drug Corp. -- are also in the list and had a combined profit of P1.49 billion in 2007. (See Table) In 2008, industry data from the international firm IMS Health showed that the global drug industry generated sales of $733 billion (P35.18 trillion), about 20 times more than the $29.78 billion (P1.22 trillion) national budget of the Philippines for the same year. With the drug industry “economically larger than many nations," governments find it difficult to regulate their quest for profit at the expense of millions of poor people who cannot afford essential drugs, according to the advocates’ group Consumers International. (See: Drugs, Doctors and Dinners: How drug companies influence health in the developing world)

Sixteen of the top 20 drug companies in the Philippines are multinational firms with combined sales of P58.23 billion in 2007, nearly eight times more than the Philippines’ P7.39 billion GDP in 2008. The companies are Glaxo Smithkline, Pfizer, Wyeth, Sanofi-Aventis, Abbott, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche, Johnson and Johnson, Boeringher Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squib, Bayer, Schering Plough, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Servier, and Merck Inc. Their sales represent about 82 percent of the total volume sales of foreign pharmaceutical firms in the country, according to data from the PHAP. The 16 companies' average compound annual growth rate of 8.5 percent in 2007 is higher than the Philippines' real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 7.3 percent in the same year. At least 10 of the multinational drug firms were among the Philippines’ top 1,000 corporations in 2007, with a total net income of P6.91 billion. Other major players in the Philippine drug industry that package, distribute, and sell drugs -- Zuellig Pharma Corp., Interphil Laboratories, Inc., Metro Drug Inc. and Mercury Drug Corp. -- are also in the list and had a combined profit of P1.49 billion in 2007. (See Table) In 2008, industry data from the international firm IMS Health showed that the global drug industry generated sales of $733 billion (P35.18 trillion), about 20 times more than the $29.78 billion (P1.22 trillion) national budget of the Philippines for the same year. With the drug industry “economically larger than many nations," governments find it difficult to regulate their quest for profit at the expense of millions of poor people who cannot afford essential drugs, according to the advocates’ group Consumers International. (See: Drugs, Doctors and Dinners: How drug companies influence health in the developing world)  Click the diagram to enlarge

Click the diagram to enlarge