How the President's veto works on the national budget

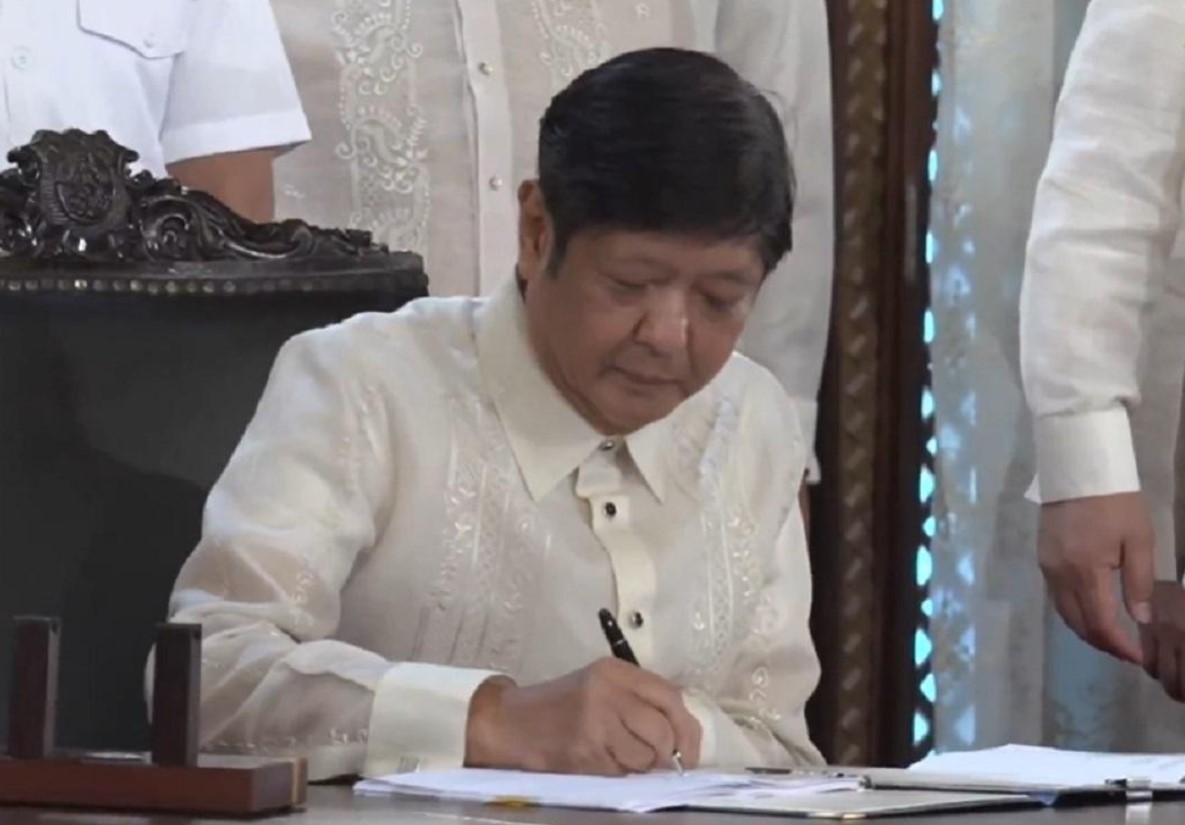

Amid concerns about some provisions of the 2025 General Appropriations Bill, which contains the government's spending plan for next year, Executive Secretary Lucas Bersamin on Wednesday said President Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos is set to veto some items in the national budget that were proposed by Congress.

But how does the President's veto powers work on the national budget?

Dictionary.com defines veto as the "power or right vested in one branch of a government to cancel or postpone the decisions, enactments, etc., of another branch, especially the right of a president, governor, or other chief executive to reject bills passed by the legislature."

Under the 1987 Constitution, every bill passed by Congress is subject to the president's approval or veto.

According to Senate Minority Leader Aquilino "Koko" Pimentel III, a former Senate President and a lawyer, ordinary measures vetoed by the president are considered outrightly rejected.

However, the Constitution exempts revenue, tariffs, and appropriations like House Bill No. 10800 or the 2025 national budget from rejection or total veto.

Article VI, Section 27(2) provides that the president can "veto any particular item or items in an appropriation, revenue, or tariff bill, but the veto shall not affect the item or items to which he does not object."

This is what lawmakers call a "line-item veto."

"Ang budget law is a special kind of law in the sense na d'yan lang ina-allow 'yung line-item veto. Sa ibang mga laws, all or nothing 'yun. Ive-veto the entire law. Sa budget law, dahil sa napakahaba niyan at t'yaka napakaraming mga entries, in-allow ng constitution na by line ang pag veto. So pag naveto yun, nawalan ng legal basis to spend," Pimentel said.

(The budget law is a special kind of law in the sense that it is one of the measures where line-item veto is allowed. For ordinary bills, it's all or nothing. The entire bill will be vetoed. The constitution allows the president to veto line-by-line budget bills because this measure has lots of provisions and entries. Once a line of the budget measure is rejected, there will be no legal basis to spend for a specific program.)

"Ngayon, pipirmahan pa rin ng presidente 'yung bill, magiging law pa rin 'yung bill, pero iko-communicate niya sa Congress na ito 'yung mga vineto ko," he added.

(Now, the president will sign the bill and it will become a law. But he will inform Congress which items he vetoed.)

Several lawmakers have raised their concerns on some provisions of the 2025 GAB as the final version of the budget bill was only discussed by the chairpersons of the Senate Committee on Finance and the House Committee on Appropriation when the bicameral conference for HB 10800 was convened.

Some senators are particularly concerned about the P26 billion funding for the controversial Ayuda sa Kapos ang Kita Program or AKAP, the reduction in the budget of the Department of Education (DepEd), and the zero subsidy for the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth).

There were also statements on possible violations of the Constitution after the bicameral conference committee increased the budget of the Department of Public Works and Highways to P1.1 trillion, which some legislators claimed was higher than the total funding for the education sector.

Article XIV of the 1987 Constitution states that "the State shall assign the highest budgetary priority to education."

Should the president veto these controversial budgetary items, Pimentel said the proposed funding for the specific program "cannot be realigned to some other items."

Budget Undersecretary Goddess Hope Libiran describes the budgetary items in the GAB that are vetoed by the president thus, "As if they do not exist."

"A veto deletes the vetoed items—- as if they do not exist. The effect is that it would require a much lesser amount that needs to be borrowed to fund the total GAA (General Appropriations Act) because of the vetoed items," Libiran told GMA News Online.

This is not the first time that line-item veto has been exercised by the president.

To recall, Marcos Jr. has exercised this power in the 2024 budget law where he rejected the budgetary item for the Department of Justice's (DOJ) revolving fund and the item pertaining to the implementation of the National Government's Career Executive Service Development Program (NGCESDP).

Marcos did the same for the 2023 national budget law, the first budget law that he signed as president.

Possible remedies

To avoid possible constitutional challenge, particularly on the higher allocation on DPWH compared to the education sector, Pimentel said the president could veto funding for several infrastructure projects.

"Kung mag-line item veto sa mga line items about infrastructure... kapag na-veto ngayon 'yun, ibig sabihin naman wala nang legal basis to spend those amounts, i-minus na yun sa P1.1 trillion ng infrastructure budget to come up with a new total for infrastructure expenditure," Pimentel said.

(If some line items on infrastructure are vetoed, there is no more legal basis to spend those amounts, and that can be deducted from the P1.1-trillion budget for infrastructure to come up with a new total for infrastructure expenditure.)

"Kung mas mababa 'yan sa education sector na total budget, ibig sabihin compliant tayo sa constitution where it is stated that education shall enjoy the highest budgetary priorities," he added.

(If that is lower than the budget of the education sector, then we become compliant with the Constitution which states that education shall enjoy the highest budgetary priorities.)

Should this be, Pimentel said Malacañang may not realign funds from vetoed items to the education sector, particularly to DepEd, whose P10 billion budget for computerization was slashed in the final version of the 2025 GAB.

It may only augment the budget through savings stored in the National Treasury.

"In the course of the year, mayroong savings. Pwede i-augment, kasi may bahay, may line item. Nasa Constitution din naman 'yung power ng presidente to realign items under the Executive Branch," he said.

(Over the year, there will be savings. These may be used to augment the line item. It's provided under the Constitution that the president may realign items under the Executive Branch.)

The augmentation after the budget is approved may also be done to PhilHealth which received zero subsidy from the national government for 2025 under the bill.

"'Pag naging law na, zero ang subsidy ng PhilHealth. In the course of the year, may savings... He can now use the savings to augment or he can actually use the contingency fund," Pimentel said.

(When it becomes a law, PhilHealth will receive zero subsidy. Over the year, there will be savings... He can now use the savings to augment or he can actually use the contingency fund.)

Senate President Francis "Chiz" Escudero said a line item's allocation may be augmented after the enactment of the appropriations bill.

"Augmentation occurs after. In any agency, whether the Executive, the Legislative, the Judiciary. It happens after the budget is passed," said Escudero, a former chairman of the Senate Committee on Finance and a lawyer.

According to Escudero, this power to augment the budget is bestowed upon the heads of agencies.

"It's in the special provisions. The Speaker, the Senate President, the President, the Chief Justice, all the heads of the agencies, the constitutional agencies have that because they have fiscal autonomy," he explained.

Another remedy for the president is to return the ratified 2025 GAB to Congress and reconvene the bicameral conference to amend the budget bill.

Marcos' sister, Senator Imee Marcos, and Senator Juan Miguel Zubiri have said that Malacañang could return the budget bill to Congress for its revision.

Zubiri and Imee earlier said this option had been done before, citing the case of the Coco Levy Fund Bill and Magna Carta for Seafarers, among others.

"Better to have an improved budget law than just to ignore a bad budget law," Pimentel said.

The only problem in this option is the bicameral committee should be reconvened and the revised GAB should be ratified while Congress is in session. The last day of session in both Houses of Congress is on December 18.

Should Malacañang opt to return the GAB to Congress, the President may call for a special session.

Override power

While the Constitution provides powers for the president to reject the Congress' proposal, it also gives the Legislative Department the authority to overturn the veto under Article VI, Section 27.

"Pwede mag-insist ang Congress na, 'Hindi! Kailangan maging batas pa rin 'yan.' Puwede mag-insist by two-thirds vote of Congress per house. Voting separately [to] override the veto," Pimentel said.

(Congress could insist that the vetoed bill or provisions should be enacted into law. The Legislative Department could override the president's veto by two-thirds vote of Congress per house.)

However, Pimentel recalled that this power of Congress to override the president's veto had not been exercised before.

"Wala. Kasi special majority ang kailangan eh. More than just simple majority. Eh siyempre mga allies ng presidente naman ang nasa House at tyaka nasa Senate," he said.

(There's none. Because the override needs a special majority, not just a simple majority. How could you do that if the members of the House and the Senate are allies of the president?)

Reenacted budget

With Malacañang postponing the supposed signing of the 2025 GAB by December 20, it is not clear if the national budget will be signed right on time before the year starts.

So what will happen if the 2025 national budget is not signed by Marcos by the end of the year?

Article VI, Section 25(7) states that "[i]f, by the end of any fiscal year, the Congress shall have failed to pass the general appropriations bill for the ensuing fiscal year, the general appropriations law for the preceding fiscal year shall be deemed reenacted and shall remain in force and effect until the general appropriations bill is passed by the Congress."

This is commonly called the "reenacted budget."

"May mga times naman sa past years na dumating na ng January 1 ng new year wala pang na-enact na budget law. Anticipated naman yan ng constitution," Pimentel said.

"Ang sabi non you operate in previous year’s budget. So it's not really an emergency. It's not really chaotic. Walang problema. It's better to have an unacceptable budget law than just to have one just for the sake of having one," he added.

(There are times in the past years that there's no new national budget law at the start of the year. That instance is already anticipated in the Constitution that's why it stated that the government could operate using the previous year's budget. So it's not really an emergency. It's not really chaotic. Walang problema. It's better to have an unacceptable budget law than just to have one just for the sake of having one.) —NB, GMA Integrated News