A pathologist, a priest and a hunt for justice in the Philippines

The same day Aurora Blas found her husband’s body in a Manila funeral home in 2016 with a bullet hole in his head, she signed a document provided by the mortician saying pneumonia had killed him. That decision has haunted her.

She couldn’t afford an autopsy, so she agreed to the lie in order to bury her husband. Like others who lost loved ones in the surge of vigilante-style killings in the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte, Aurora said she was compelled to accept a death certificate that failed to acknowledge what everyone knew: Her husband was shot dead by unknown assailants, another casualty in the nation’s drug war.

Nearly six years later, Aurora’s desire to set the record straight has brought her to Raquel Fortun, a forensic pathologist at the University of the Philippines Manila. With the consent of the families and the help of a Catholic priest, Fortun is examining the exhumed remains of some of the poorest drug war victims to document how they died.

“It’s definitely not pneumonia,” said Fortun, as she identified a gunshot hole in the exhumed skull of Aurora’s husband.

Human rights groups claim that Philippine police and vigilantes under their direction murdered unarmed drug suspects on a massive scale on Duterte’s watch, allegations that authorities have denied. The International Criminal Court (ICC) last year announced it would pursue an investigation of suspected crimes against humanity; it estimates that somewhere between 12,000 and 30,000 people were killed between July 2016 and March 2019. Last year Harry Roque, Duterte’s spokesperson at the time, said his government “will not cooperate” with the ICC investigation, claiming it was “legally erroneous and politically motivated.”

The Philippine government, whose drug war death tally runs through April 2022, officially acknowledges 6,248 deaths. Duterte, who has steadfastly defended his drug war and denied any wrongdoing, is due to leave office June 30 when his six-year term expires. In a statement to Reuters, his office said the administration’s “relentless” fight against illegal drugs had produced significant accomplishments and it was confident the country’s justice system is working.

Now, in an improbable turn of events, the poverty of families upended by the killings has led to new evidence of potential misconduct. In the Philippines, grave spaces are typically rented for five years. If a family can’t afford to extend the lease, the remains are exhumed and transferred to a mass grave or cremated. Leases are starting to come due for drug war victims and some families have agreed to Fortun’s offer to examine the remains.

Fortun—known to most people as “Doc”—does most of her examinations in a cramped campus stockroom on tables she sourced from a junkyard. When the stockroom fills up, she uses the morgue at the university's medical school. She does not advertise her services and no one funds her work.

For 11 months, Reuters shadowed Fortun, the priest and families in their hunt for justice. The news agency also photographed remains of some of the deceased and reviewed official documents including death certificates and police reports.

Reuters found that the official death certificates of at least 15 drug war victims did not reflect the violent manner in which police and family members said they died. Those death certificates said the deceased had succumbed to natural causes such as pneumonia or hypertension instead of saying they were shot.

The news agency also examined the unpublished findings of the Medical Action Group (MAG), a Manila-based group of medical professionals focused on suspected human rights abuses.

MAG’s analysis looked at death certificates issued during the drug war between July 2016 and June 2019. It focused on 107 cases where families told the group their relatives died of injuries—mostly gunshots—sustained in encounters with law enforcement. The majority of those death certificates cited natural causes, used “vague terminology” for the cause of death or left it blank, according to MAG’s audit.

Accurate death certificates are essential to a family’s ability to take legal action against alleged perpetrators, legal experts said. Erroneous death records also obscure the true toll of the war on drugs.

Reuters obtained copies of all documents cited in this story. The news agency was not able to establish whether discrepancies in the death certificates it reviewed were intentional, the result of mistakes by the health officials who completed them, or the byproduct of shortcomings in the nation’s death reporting system. Reuters’ reporting found widespread problems with the country’s death investigations and record keeping that predate Duterte’s administration.

Sophia San Luis, a local attorney who has studied the Philippines’ process of investigating and registering deaths, said the system has long-standing vulnerabilities and poor standards. She said there is no mandatory training for health officials tasked with certifying deaths. Doctors who sign death certificates aren’t required to examine the bodies, even for patients they don’t know and have never treated. Instead, physicians can turn to relatives of the deceased to provide a cause of death, a practice known as “verbal autopsy,” according to guidelines by the country's Department of Health.

In addition, Reuters found that some funeral homes have grieving relatives sign in-house waivers attesting that their loved ones died of natural causes. Three people familiar with the system described it variously as a way to save poor families the extra expenses associated with an autopsy, and a way for funeral homes to shield themselves from potential complaints or legal troubles in the event relatives later end up challenging the cause of death listed on the official death certificate.

“The system is just so weak,” said San Luis, executive director of ImagineLaw, a public interest law practice. ImagineLaw documented deficiencies in how unnatural deaths are handled in the Philippines in a 2020 report commissioned by the Department of Health. Separately, the law firm in a 2017 report found problems with how the country collects and records vital records such as death certificates.

The Department of Health, which oversees some of the doctors responsible for certifying causes of death, did not respond to requests for comment about those reports. In 2020, the agency issued an administrative order recommending training on death certification for health care workers; it listed the types of deaths that should be referred to authorities for investigation, including those from gunshot wounds. It also stressed that verbal autopsies should follow a structured set of questions supplied by the Department of Health.

The Philippine Statistics Authority, which is responsible for maintaining death records, said it preserves copies of death certificates registered by local authorities across the country but does not create them.

Fortun has publicly lambasted the country’s procedures for investigating deaths. The forensic pathologist said she has found gunshot wounds, fractures—even bullets—in the nearly four dozen sets of remains she has examined so far, trauma that often isn’t reflected in the death certificates. At a press conference in April to discuss her findings, she criticized physicians who sign off on natural causes when registering deaths in such cases.

“You have doctors staking their reputations, names, licenses, falsifying death certificates,” Fortun said at the April 12 event without naming any physicians. She told reporters she was reserving judgment on whether there was an attempt by authorities to cover up drug war deaths with false death certificates. She said she suspected that incompetence by police and doctors was a factor and also blamed the Philippines’ inadequate death investigation system.

Whatever the reasons, inaccuracies in official death records are a problem for Filipinos seeking a reckoning for perpetrators of alleged drug war atrocities. Previous reporting by Reuters has revealed efforts by police to hide killings and destroy evidence at crime scenes.

Department of Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra told Reuters his office would “investigate and prosecute those who were responsible for the falsification of death certificates,” a crime punishable by fines and jail time of up to 12 years in the Philippines.

Duterte’s office referred questions about purported irregularities in some death certificates to the Philippine National Police.

The law enforcement agency did not respond to questions from Reuters. In a separate statement on Fortun’s findings, it said it would “probe and look into this matter.”

Aurora and the other families who have turned to Fortun say they are done living in fear and want to prove that what they’re saying about how their loved ones died is true. The first batch of their relatives’ remains arrived in Fortun’s stockroom in early 2021. They have kept coming ever since.

Exhumed and examined

Father Flavie Villanueva runs a support group for drug war families in Manila and has been anticipating the grave lease expirations. He has compiled a list of death dates and called cemeteries. For the families who agree, Villanueva oversees the exhumations and sends the remains to Fortun to examine.

He told Reuters this work is crucial to prepare for the day when a thorough investigation of Duterte’s crackdown determines “how these people were killed, and how even this war on drugs simply was an act of terror for those living in the margins.”

Villanueva met Fortun at forums on extrajudicial killings and events for drug war families. Fortun chairs the pathology department at the College of Medicine at the University of the Philippines Manila and has spent decades consulting on some of the Philippines’ biggest criminal cases.

She sometimes worries her work could get her killed. “Yes I’m scared of ending up the same way my cases did,” she tweeted in December 2020 on her @Doc4Dead Twitter account.

A vote for 'The Punisher'

Aurora told Reuters she was overseas, working temporarily as a maid in Hong Kong, when her husband Thelmo started using shabu—the local name for methamphetamine. It was the late 1990s and they had just bought a house in Caloocan City in northern Manila, she said. They needed the money from him working longer shifts and the shabu kept him awake.

Thelmo would rise at 4:30 each morning to drive a jeepney, the shiny, elongated public buses that crisscross the Philippines. Even with the four kids they would eventually have, they never went hungry, Aurora said. The entire neighborhood called Thelmo “tatay.”

When Duterte began campaigning, vowing to come down hard on drug users like Thelmo if elected president, Aurora feared for her husband’s safety. She joined a church group and prayed for Duterte not to win.

Thelmo told her not to worry. He said he had a proven system for passing the drug test needed to renew his driver’s license: He’d stop using two weeks before and drink plenty of water. He wore a bracelet with Duterte’s name on it and voted for the man nicknamed “The Punisher.”

Duterte was sworn in on June 30, 2016. On July 31, Thelmo went missing. Aurora searched three police stations without finding him. Eventually she began checking funeral parlors. She found him at the fourth one.

In the Philippines, people believed to have died of suspicious or unnatural causes are not automatically sent for an autopsy. It’s often up to relatives to request this from authorities, according to the 2020 report on the country’s system of death investigations commissioned by the Department of Health.

The staff at Jade Funeral Homes told Aurora that if she opted for an autopsy, she would have to pay an additional $286 to the funeral home for the extra work that would be required afterwards to restore the body for burial. It was money she didn’t have. The funeral home offered an alternative, Aurora told Reuters: She could sign a waiver saying Thelmo had died of pneumonia and that she didn’t want an autopsy.

Aurora agonized and then she signed. After nearly three decades of marriage, Aurora buried Thelmo. He was 47.

The police report said Caloocan City officers responding to reports of gunfire around 3 a.m. on Aug. 1, 2016, found Thelmo’s body dumped by the side of the road, his face wrapped in masking tape. He was found with three sachets of suspected shabu and a placard in Filipino that read: “I am a pusher, do not copy me.” Police claimed in their report that Aurora told them on Aug. 2 that Thelmo was “involved in illegal drug activities,” and that she had refused both an autopsy and an investigation into his death.

Aurora told Reuters she didn’t speak with police after Thelmo died, and that she wasn’t aware of the contents of the police report. She said she wasn’t provided a copy of the waiver she signed at the funeral home either.

The Philippine National Police didn’t respond to a request for comment on the status of the investigation or Aurora’s allegations that their statements about her in the police report were false.

As in other countries, funeral homes in the Philippines collect some of the information that ends up on death certificates. While a medical professional is responsible for certifying how a person died, Jade Funeral Homes manager Amalyn Yu told Reuters it asks families to sign waivers to prevent them from returning later to complain about their relatives’ cause of death, and to protect itself against potential legal liability. Yu said the funeral home fully explains this to the families. “They agree to the waiver on their own volition. We do not force them,” she said. Yu said she could not provide copies of the waivers, which she said were destroyed in a fire in late 2016.

Two other families who spoke to Reuters said they, too, were asked by funeral homes to sign waivers agreeing to a natural cause of death for their relatives in order to gain custody of the bodies.

The practice is common in the industry and predates the Duterte administration, according to Geraldine Putillas, who works on behalf of funeral homes to register death certificates with the government. She said a natural causes determination is a “way of helping” poor families avoid the expenses related to an autopsy. Putillas said these waivers are in-house documents, not official government records. Putillas did not file paperwork for any of the cases that Reuters examined.

The Department of Justice did not respond to a request for comment about funeral home waivers.

Aurora said she regrets signing Thelmo’s waiver. Her family is uneasy about her re-examining the circumstances of his death, but she feels Fortun’s analysis offers a chance at justice.

“I will go ahead and fight,” she said.

A violent front line

One of the front lines of the drug war was Caloocan City. Like Aurora, other residents there told Reuters their loved ones’ death certificates didn’t match their violent ends.

On Sept. 14, 2016, unidentified men knocked on Erwin Garzon’s door and shot him in the head, according to the police report. The document said police were checking to see if Garzon was on a watch list for people they suspected of illegal drug use. Garzon’s death certificate says pneumonia killed him.

Garzon’s family was too grief-stricken to argue about the pneumonia determination, said his mother, who asked not to be named. “Besides, we thought we knew what really happened anyway,” she said.

Records of Roger Nicart’s death show a virtually identical pattern. According to the police report, he was killed inside his home, which a community leader had described as a “drug den,” on Oct. 1, 2016, by masked intruders who shot him several times. “His brains splattered on our curtains,” Nicart’s Aunt Rebecca told Reuters. His death certificate said he died of pneumonia.

Police didn’t respond to requests for comment on the status of those investigations. Amadea S. Cruz, the medical officer who certified the death certificates of Garzon, Nicart and Thelmo Blas, is deceased. The Caloocan City Health Department, where she had worked, did not respond to a request for comment.

In nearby Quezon City, Reuters found the family of a man who had been issued two conflicting death certificates.

Police said they shot Constantino De Juan in self-defense on Dec. 6, 2016, in an undercover drug operation involving 35 officers. He was pronounced dead on arrival at a hospital in Quezon City, according to the police report.

De Juan’s first death certificate, dated Dec. 6, 2016, said he died of three gunshot wounds. It was certified by Divina Castañeda, a physician at the hospital. Castañeda could not be located for comment.

The second death certificate, dated nine days later, said De Juan died of acute myocardial infarction, or a heart attack, and hypertension. That death certificate came from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) and was certified by a different physician, Kathleen Timogan. Timogan did not respond to a request for comment.

Death certificates are filed with local civil registrars, then collected by the PSA. The agency did not respond to requests for comment about de Juan’s case, but said there are various reasons a person might be issued more than one death certificate, including if a relative tried to correct errors in the original document.

De Juan’s wife Lourdes said she only learned about the second death certificate recently, when her husband’s grave lease expired. The cemetery required a PSA-issued death certificate to process his exhumation.

Lourdes’ daughter, who was 12 years old then, witnessed her father’s killing. The child watched as the police made him lay face down, shot him three times, then planted a white crystalline substance, money and a gun on his body. Reuters spoke to the girl, who confirmed the details, but is not naming her at her mother’s request because she is still a minor.

Police “said my husband fought back,” Lourdes said. “There’s no truth to that.” She asked Fortun to look at his remains.

When Fortun examined de Juan in March, she found a bullet in his left arm, and fractures in his skull and ribs. “Not natural,” Fortun told Reuters.

The Philippine National Police did not respond to a request for comment.

"Alleged' shooting'

Rodrigo Baylon is perhaps the most vocal of the relatives challenging the official death records of their loved ones. He has taken the fight to correct the death certificate of his 9-year-old son Lenin to the Philippine courts.

The fourth grader was killed by stray bullets on Dec. 2, 2016, in Caloocan City in a shooting that also killed two women, the police report said. The document said three unknown assailants fled the scene, and that police found shabu on one of the dead women. Lenin’s death certificate says he died of bronchopneumonia that took a month to kill him.

The Philippine National Police did not respond to a request for comment on the status of the investigation.

Zenaida Calupa, the doctor who certified Lenin’s death certificate, denied wrongdoing. She said she didn’t recall Lenin’s case but said physicians who sign death certificates often don’t examine the bodies, depending instead on relatives to provide a cause of death, which is lawful in the Philippines. “We rely on the declaration of the family,” Calupa said.

Baylon said in sworn testimony to a Caloocan City trial court on Jan. 6, 2020, that the family agreed to sign a waiver saying the boy had died of illness because police told him the true cause of death could be determined later and the funeral home told him it would be easier to claim his son’s body.

“I wanted to bring home the body of my child,” Baylon said in his testimony. “I never thought of what would be its implications.”

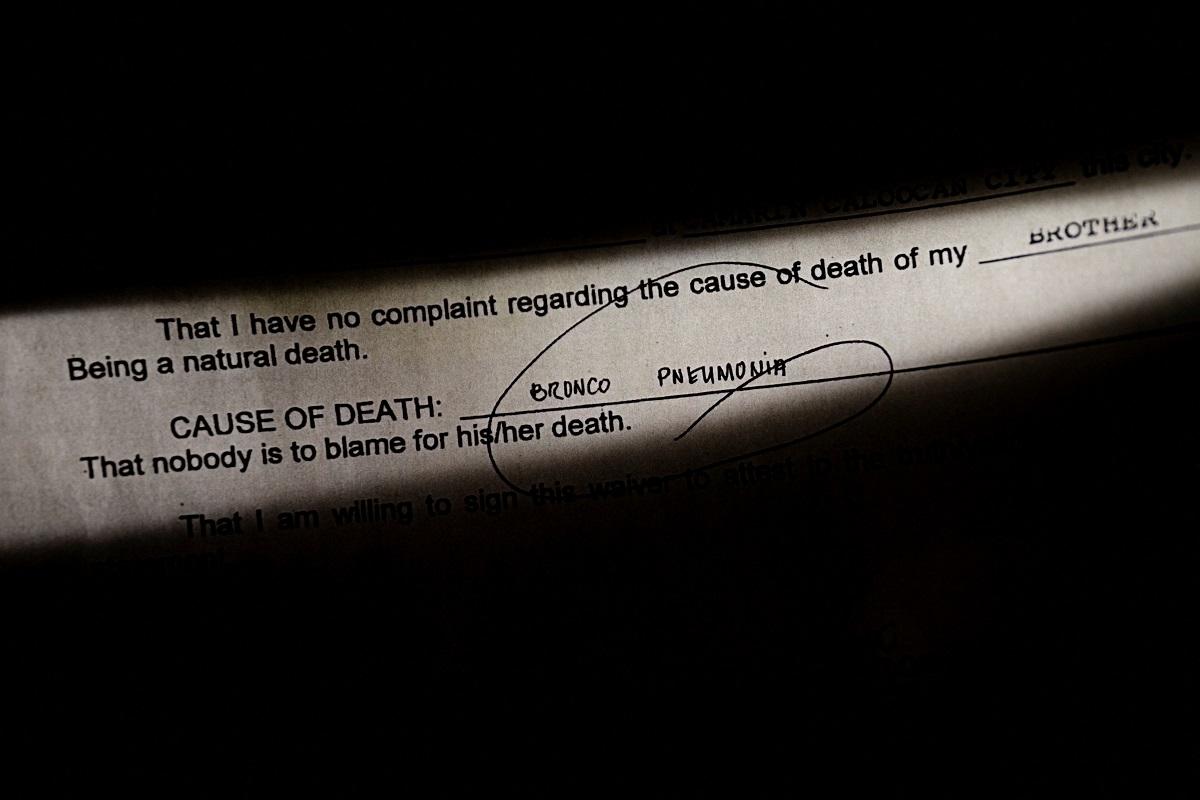

Reuters saw Baylon’s copy of the waiver provided by Three Lights Funeral Homes. It said the family had “no complaint” and “nobody is to blame” for Lenin’s death.

The Philippine National Police did not respond to a request for comment on whether they told Baylon his son’s true cause of death could be determined later.

Reuters could not reach Three Lights Funeral Homes for comment. A music store now occupies the storefront where it once operated.

On Aug. 3, 2020, Judge Rosalia Hipolito-Bunagan denied Baylon’s petition “for utter lack of merit.” Among her objections: The medical certificate signed by the hospital doctor who had treated Lenin referred to an “alleged” shooting.

Her decision is currently on appeal. Baylon’s lawyers said in their initial 2019 petition that if Lenin’s death certificate is left uncorrected, it “will foreclose the right of petitioner to seek justice.”

Caloocan City Assistant Prosecutor Michelle Guiyab declined to comment on Baylon’s petition because it is still pending. She told Reuters the government is willing to correct mistakes on death certificates, but said such documents contain “a presumption of truth.”

The hunt for justice

For years, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has received complaints and testimonies from individuals and groups calling for Duterte’s indictment for thousands of drug war killings. Last September, ICC judges authorized an investigation.

That probe is now on hold as the court considers a deferral request from the Philippines, which asserts the country can adequately investigate itself. An ICC spokesperson declined to comment on when a decision would be made.

Fortun, the forensic pathologist, and priest Villanueva have talked about trying to preserve some sets of remains for foreign forensics teams to examine. But space at the university is tight. For now, after Fortun finishes her examinations, the remains are cremated and returned to the families.

Three families of drug war dead told Reuters that police last year visited their homes, asking if they planned to press unspecified “charges.” They said they wouldn’t. The families believe it was an attempt at intimidation, but also a sign that authorities may be concerned about the ICC’s scrutiny.

The police did not respond to a request for comment.

Aurora’s husband Thelmo was exhumed in August. When Fortun emptied his remains onto a table, the bracelet with Duterte’s name on it fell out. Thelmo had been scared when the killings started, Aurora said, but he never took the bracelet off, and she had buried him with it. It was one of the only things still identifiable.

By October, Thelmo had been cremated. Villanueva asked seven families to gather in a church to receive the ashes of their loved ones. Aurora went alone.

At the end of the prayers, Fortun found Aurora clutching Thelmo’s urn. They talked about Aurora’s gratitude towards Villanueva. They compared notes on the bullet hole in Thelmo’s skull and discussed documentation Aurora could use to pursue justice.

Then Fortun said she had something to say: “Don’t lose hope.” — Reuters