Over 100 laws unfunded, under-funded for years

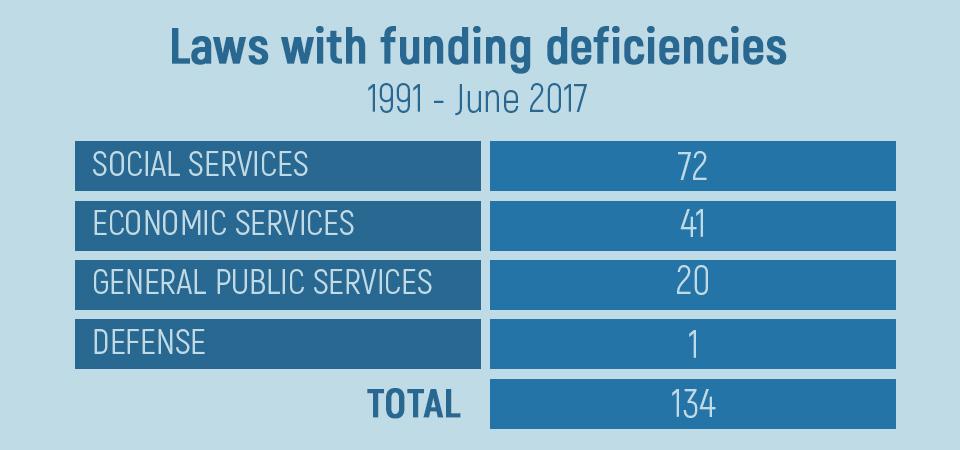

At least 134 laws did not receive funding or remained underfunded as of last year, government documents obtained by GMA News Special Assignments Team showed.

Some of the unfunded laws were enacted more than two decades ago in the Ninth Congress when the late Neptali Gonzales and the retired Edgardo Angara were the Senate Presidents, and the similarly retired Jose De Venecia was the Speaker.

The Department of Budget and Management (DBM) pegged the cumulative funding requirement at P82.6 billion pesos, a "conservative" figure considering that 111 of these laws are non-quantifiable, or do not state in absolute figures the money needed to fund their implementation.

"Conservative lang 'yun. The rest, hindi mo ma-identify kung magkano [ang funding requirement]," Budget and Management Secretary Benjamin Diokno told GMA Special Assignments Team.

While the 2018 General Appropriations Act (GAA) has already been signed into law, the DBM said it only made such lists of unfunded laws once a year. The list for 2018 will be released later this year.

Majority of these laws (72) are related to social services such as education, health, housing and jobs.

The oldest item on DBM’s record is the National Dairy Development Act of 1995, which was listed as underfunded by over a billion pesos some 22 years after its implementation. It was enacted to accelerate the development of the local dairy industry.

Also awaiting funds is Republic Act (RA) 10645, which provides for Mandatory PhilHealth Coverage for all Senior Citizens. It was in need of nearly 21 billion pesos three years after its approval.

Both the National Dairy Authority and PhilHealth cited the government’s prioritization of other programs over theirs. PhilHealth said: "The said unprogrammed fund was not released to PhilHealth in favor of DOH's health facilities enhancement program."

Attorney Yolanda Doblon, Director General of the Senate Legislative Budget Research and Monitoring Office, prioritization is indeed a reality in government because of limited funds.

However, she cited other governance issues that affect the release of funding. “One reason would be that in the law itself, it could require a condition before funding. For example, a law would say that funding will be provided once it is organized and personnel are appointed. So once that condition is not met, then no funding will be available,” Doblon said.

She added that, “Some laws would require implementing rules and regulations (IRRs) before its implementation. Usually, the IRR will determine the amount needed. So if the IRR is not yet [ready], the process is not yet prepared, DBM could not provide funding.”

‘Parochial interests’

Over a hundred (105) of these laws deal with local concerns instead of national matters.

Fe Mendoza, dean of the UP National College of Public Administration and Governance (NCPAG), said this was indicative of the perspectives of many lawmakers.

“Kapag titignan kasi ‘yung mga unfunded laws ay parang constituency-based. National high school dito, o kaya health unit or a hospital dito. ‘Yung ganun. So ito kasi ‘yung mga demand doon sa mga lugar at ‘yun nga gusto nila na meron silang mga achievement,” Mendoza said.

For her part, Doblon did not see any problems with lawmakers focusing on the plight of their constituents.

“Parochial interests, that is alright. Because remember that Congress is made up of the House of Representatives and the Senate. The House of Representatives ay elected by district. And of course, dahil elected by district, meron silang, magke-cater sila sa mga interests ng distrito nila. And even the Constitution recognizes that,” Doblon said.

Ignored views

Diokno admitted that there were challenges in Congress moving laws towards enactment and subsequent funding.

"Binabantayan namin lahat ng budget na ‘yun. At responsibilidad ng chairman ng committee na ipa-comment sa amin. Kaya ba ng gobyerno ito? At the committee level pa lang, nagco-comment na kami kung ito ba matutustusan over a period of many years o hindi," Diokno said.

"Merong mga batas na ini-ignore nila (lawmakers) ang views namin," he added.

Sought for comment, Davao City Rep. Karlo Nograles, chair of the House Committee on Appropriations, said, “There are a higher number of good laws now, whether national of local, which are economically viable and with strong belief that the Executive Department will provide the required funding in the GAA (General Appropriations Act).”

Fulfilling promises

Mendoza said the situation showed gaps in the approval and consultation processes between the executive and legislative branches.

"Kasi minsan sa diskusyon nila, kung maganda talaga ‘yung proposal, sige go na. Minsan, nakakalimutan na ‘yung kailangang admin, financial, logistical, and technical requirements," Mendoza said.

“Sa ngayon, parang unfulfilled [‘yung batas] kasi nag-promise ka na maglalagay ka ng ganito pero wala ka namang pondo so paano siya ipapa-implement? ‘Di ba sabi sa atin, huwag ka magpa-promise na hindi mo matutupad,” she added.

“Ideally sana kapag nag-propose ng batas, nai-consider na halos lahat ng components para maipatupad ng maayos ‘yung batas.”

Bridging the gap

In a letter late last year, DBM Undersecretary Laura Pascua noted that the 82.6-billion peso total funding deficiency was 14.6 billion pesos or 15.1 percent lower than the 2016 level of 97.2 billion pesos. "This funding status already reflects the actual releases as of 2016 and allocations as provided under the 2017 GAA and the proposed FY 2018 budget," Pascua wrote.

Factored into the computation were further allocations in the FY 2018 budget mainly for: the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program Extension with Reforms (CARPER), 10.3 billion pesos; Mandatory PhilHealth Coverage for Senior Citizens, 17.0 billion pesos; the Armed Forces of the Philippines Modernization Program, 25.0 billion; and, modernization of Pagasa, 1.5 billion pesos. —NB, GMA News