Filtered By: Sports

Sports

ANALYSIS: How 'undervalued talents' can bring the Philippines to the World Cup

By ROY MOORE

This is the last of a four-part series on the future of Philippine football. Check out Part One, Part Two, and Part Three of the series.

The concept of Moneyball is to use statistics to understand the game better than your opponents and find undervalued talents to build a great team on a small budget.

In that respect, there is one gaping crack in youth development systems all across the world. The biggest factor enabling a child to become a professional athlete has less to do with talent or hard-work, it is the month in which they were born.

That’s because January 1 is the cutoff date for youth sports in most countries. Everyone in that birth year is put together and treated as if they are the same age, but they’re not. Players born in January or February are almost a year older than those born in November or December. When you’re 25 years old it doesn’t make much difference, but at six or eight, the age when kids are usually selected for elite trainings, this is huge.

Those born earlier in the year effectively had more time training, studying, and growing. They’re taller, faster, and technically better on average – not because they are in fact better, just because they’re older. They get selected for elite programs, and this extra training and coaching makes them better, in a self-fulfilling prophecy.

It’s called the relative age effect, a concept popularized by books like "Outliers" and "SuperFreakonomics." In "Outliers," Malcolm Galdwell gives the example of the 2007 Czech junior football team where 15 of 21 players were born in January, February, or March, and only two born in the second half of the year.

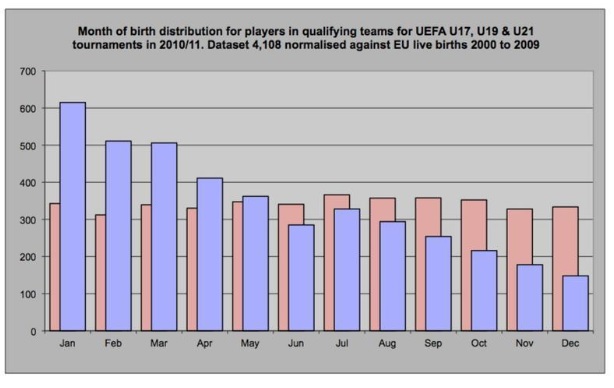

This is an extreme case, but the overall effect is clear. Take a look at the graph below for a powerful visualization, charting U17, U19, and U21 players in the qualifying stages for UEFA competition by birth month. The pink bar is the number of players you’d expect from that month, i.e. the proportionate number of births, while the blue bar is the actual number of athletes born in that month. The result? Four times the number of players are born in January as December.

Closer to home, in the 2014 Suzuki Cup, 25 out of 175, or one in seven players, were born in January, a similar proportion to the UEFA figures above. And this trend is only growing as grassroots selects children at younger and younger ages.

The relative age effect is therefore the biggest crack in youth development programs in sports, and even academia as that too arranges children into year groups.

In "Outliers," Gladwell recommends breaking birth years for tournaments into two to minimize the effect. More practically, building futsal courts would level the playing field, particularly in poorer barangays with developing teams. No matter what month you’re born in, then, you could still rack up your 10,000 hours with somewhere to play.

Meanwhile, training scouts and coaches to better understand potential over ability (some already do) would aid in better youth development, maximizing our young talents in ways most countries don’t.

Getting to the World Cup

Everything so far in this series has been about building a team capable of winning the Suzuki Cup. The World Cup is an entirely different ball game, figuratively of course.

In the long run, the Philippines has advantages. FIFA is likely to increase slots for Asian countries and even if they don’t we have to beat one of Japan, South Korea, Iran, or Australia in a group stage for one of four automatic spots. No mean feat, for sure, but it’s easier than beating the likes of Uruguay or Mexico in a playoff.

Yet given where Philippine football is at right now, this conversation is still decades away – if, and only if, youth development is well on its way by then. But there is a way we can talk about qualifying for the World Cup right now,

Women’s football has huge potential in the Philippines. One of the reasons is the Philippines are ranked ninth in the world for gender equality. Relatively speaking there’s little or no barrier to entry for young girls in sport.

And those who have gender equality understandably create very strong women’s teams.

Of the top ten, only Nicaragua, Rwanda, and the Philippines are not also in FIFA’s top 30, while only Rwanda and Belgium’s women are ranked lower than their men (at the time of writing).

Of the top ten, only Nicaragua, Rwanda, and the Philippines are not also in FIFA’s top 30, while only Rwanda and Belgium’s women are ranked lower than their men (at the time of writing).

What makes this even more remarkable is the other nine countries have very small populations, ranging from 350,000 in Iceland to 11.2 million in Belgium. The Philippines has almost twice the population as the rest combined.

To qualify for the Women’s World Cup, the Philippines would have to finish in the top five of the Asian Cup. Japan, Australia, South Korea, and China took the four automatic places as top two in each group, while Thailand, ranked 31st in the world, beat Vietnam (34th) 2-1 to win the playoff. They now face Germany, the Ivory Coast, and Norway in the 2015 World Cup.

Incidentally, Thailand’s sole win in the Asian Cup group stage came against Myanmar (44th). In other words, there’s already a spot in the Women’s World Cup for the top side in Southeast Asia.

At their best, the Philippines' Malditas aren’t far behind. In June 2013 for the Asian Cup Qualifiers, the Malditas thrashed Iran 6-0 and beat Bangladesh 4-0. Only the group winner qualifies, though, and Thailand narrowly beat the Philippines 1-0.

Yet all the progress and optimism was completely erased in the disastrous SEA Games campaign later that year, losing 2-0 to Myanmar and thrashed 7-0 by Vietnam. The whole debacle ended in a player stranded at the airport allegedly because a stolen credit card was used to book her ticket. Last February the PFF promised an investigation of head coach Ernie Nierras; a year later there’s still no word.

Neither has anything happened for the Malditas. Not a single international women’s game since the fiasco. Given FIFA doesn’t rank teams inactive for 18 months, the Malditas are only a few months away from dropping to the bottom and having to start again from scratch.

PFF General Secretary Ed Gastanes said this is due to cost, as many players are based in the USA they wanted to instead “harness more local players here because it’s really expensive to be flying in players… we don’t have enough women’s matches here… so we organized the nine a side invitational”.

PFF General Secretary Ed Gastanes said this is due to cost, as many players are based in the USA they wanted to instead “harness more local players here because it’s really expensive to be flying in players… we don’t have enough women’s matches here… so we organized the nine a side invitational”.

In fairness, Pinay Futbol deserve much credit for that nine a side invitational. But hearing the PFF say a national team is too expensive is rather unimpressive.

Gastanes, however, added: “We don’t have a Coach right now. We have two candidates, Lelet Dimzon and Buda [Bautista]… Coach Ernie is not an A [licensed coach] so cannot coach the women’s.”

In other words, Nierras is apparently no longer head coach of the Malditas. And perhaps this is an opportunity because with the right leadership the potential is huge. Women’s football around the world tends to feed off scraps from the men’s but the Philippines can flip that formula on its head, bringing with it global attention and improving the rest of Philippine football to boot.

The U14 Girls became the default example for this potential in winning silver at the ASEAN U14 Regional Championship with just one month’s training, while some opponents train all year round. So when you add up the underlying conditions and impressive youth performances, the women are probably the most undervalued talents in Philippine football. —JST, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular