How the UAAP became the country's premiere basketball league

In 1938, long before people paid more attention to their mobile phones than actual human connections, four universities got together for some good ol’ competition.

Student-athletes from the University of the Philippines, University of Santo Tomas, National University, and Far Eastern University faced each other in basketball, women’s volleyball, baseball, football, swimming, and track and field.

Eighty years and four more member schools later — the University of the East, Ateneo de Manila University, Adamson University, and De La Salle University — the University Athletic Association of the Philippines (UAAP) lords it over the country’s collegiate sporting scene. That’s quite a feat for a league dwarfed in popularity by their kuya/rival, the 1924-born NCAA, and the PBA for most of its existence.

The UAAP’s resurgence began with its centerpiece sport, the Senior Men’s Basketball tournament.

It’s arguably the most profitable franchise today on Philippine TV, with big ratings and advertising spots for everything from a good pass on the hardcourt to a group of students on the bleachers cheering for their peers.

So how did a basketball league that could barely stay relevant grew into super-fame status? Below are the most important moves the UAAP (and fate) made to become the best hoops show in the land.

“Hey, look, we’re on TV!”

UAAP games have been on TV since the late ’70s. The production groups that handled the coverage bought airtime on government channels IBC, PTV, and RPN, to air the games. Not all playdates went on air though — that distinction belonged to key matchups in the elimination rounds and the playoffs.

Save for the action on-court, the televised games weren’t also the prettiest to watch. It was basically two older dudes who knew basketball talking over a video feed of college jocks duking it out.

Then in 2000, as the league was beginning to gain prominence, the UAAP transferred to network TV, giving the league a bigger audience, which meant they had to improve their “product.”

Player profiles, taped segments, and a new breed of on-camera personalities called “courtside reporters” were introduced. The latter, composed of students from UAAP schools who served as special correspondents assigned to a team, would soon gain notoriety on its own. The hardest of basketball buffs even pride themselves in being knowledgeable in both team lineups and courtside reporter batches. As further proof of the league’s growing popularity, some courtside reporters have even managed to cross over to a career in broadcasting, like GMA News and Current Affairs’ Pia Arcangel.

For school pride

“The UAAP brand of play and officiating was much more exciting because the referees allowed the players to play freely,” wrote champion coach Tommy Manotoc last year on his column in the Philippine Daily Inquirer. “Players dove for the ball and ended on top of each other without drawing a foul. Minimal contact was allowed.” He then compared this to the PBA’s brand of play and rued how the pro league often halted games for what he thought were touch fouls, “taking the flow out of the games.”

Now, add what Coach Manotoc said to the fact that UAAP teams are made up of young players looking to make a name for themselves, and you’ve got the perfect recipe for hard-nosed, good-for-TV basketball. But that’s not all, some UAAP games are also steeped in decades-old bad blood.

The Green — Blue Rivalry

Sure, the NCAA practically has the same on-court formula as the UAAP, letting young players play the game. They also share a love for basketball feuds. In fact, the greatest rivalry in Philippine pop culture started in the NCAA. That they lost it to the UAAP when the Ateneo Blue Eagles and La Salle Green Archers switched sides, in 1978 and 1986 respectively, might be one of the saddest break-up stories in history.

So what’s so special about Ateneo versus La Salle? Well, they really hate each other. And it’s not just “I-hate-you-because-you-make-me-asar-sometimes,” for some it’s “I-hate-EVERYTHING-about you-from-the-way-you-part-your-hair-to-that-ugly-green/blue-Jordans-on-your-feet.”

La Sallians abhor that Ateneo’s greatest UAAP season (the Cinderella Run of 2002) came at their expense. Ateneans can’t stand the fact that La Salle now has more titles than they have (DLSU – 9, ADMU – 8). There are plenty of other reasons for their players to get rile up, guaranteeing great games and then some.

Share the glory

Thirty years after renewing their rivalry in the UAAP, Ateneo and La Salle have won the Senior’s Basketball championship 16 times. The two universities have somewhat dominated the league, but the other member schools aren’t far behind.

If UAAP officiating allows a freely played game, fandom allows rabid loyalty.

How rabid? Well, consider this: For all the hype that surrounds an Ateneo – La Salle game, the rivalry doesn’t own the best numbers in league history: 25,138 and 15.3. The former is the attendance record, set during Game 3 of the 2014 finals between the NU Bulldogs and FEU Tamaraws. The latter is the TV rating record, which belongs to the Game 3 telecast of the 2013 finals between La Salle and UST Growling Tigers.

It all boils down to school pride, a concept the UAAP carefully nourished through time. Champions are celebrated like royalty, sent to TV shows to goof off with celebrities. The name of their school is plastered on billboards and other spots conducive for exercising bragging rights. Shirts and other swags are printed out. In turn, students, alumni, parents, and bandwagoners claim victory.

After a week or so of being bombarded of another’s great conquest, envy will kick in for the other schools. They’ll assemble a better team, hire a better coach, spend more for training, encourage more students and alumni to watch. It’s a vicious, beautiful cycle that the UAAP has perfected.

The players

However, this cycle won’t continue if the games suck. And to have great games, you need good players.

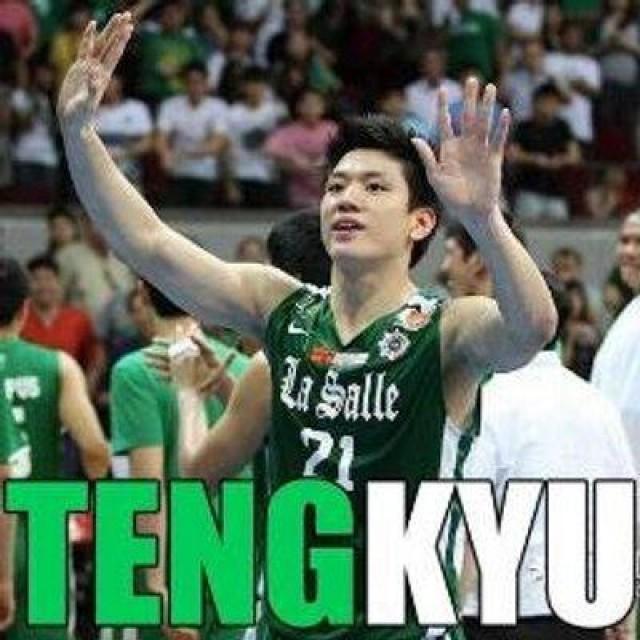

The fame borne out of the UAAP’s Great Transfer of 2000 made it the foremost destination for the best young players in the land. From high school standouts like L.A. Tenorio and Jeron Teng, to so-called phenoms like Terrence Romeo and Kiefer Ravena, to provincial ballers like Arwind Santos and James Yap, they all knew that the path to stardom goes through the UAAP.

Add players like Paul Lee, Jeff Chan, and Greg Slaughter to that group, and you can argue that the UAAP has produced some of the best professional cagers playing today. Likewise, add names like Chris Tiu and BJ Manalo, and you now have some of the most marketable players in basketball.

The Evolution

In the age of social media, having a rabid following is tantamount to a massive online presence. And when you’re as big as the UAAP, you practically don’t have to curate nor manage whatever is posted about you. The fanbase got your back.

They’ll troll the trolls. They’ll condemn the haters. They’ll bicker and throw insults at one another and deliver whatever hashtag you told them to use to the No.1 Trending Topic spot.

They’ll also provide you with some of the funniest works of online art Pinoy social media has ever seen.

And that, folks, is how you become the biggest basketball league in the land. — LA, GMA News