We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

Justice is supposed to be blind.

No one richer or poorer, none more entitled or less disempowered than the other.

The bare facts should be weighed on their own merits.

But what happens when the wheels of justice grind too slowly?

In Philippine society, few things can be more agonizing than being locked up in one of the local prisons. Jails and police detention facilities are meant for inmates awaiting final conviction by the courts, yet they are arguably subjected to punishment — cramped sleeping quarters, meager food, sweltering heat, and makeshift medical facilities, among others.

Pacifico Agabin, former dean of the University of the Philippines-College of Law, bemoans the plight of inmates in these jails.

“They are presumed to be innocent and yet, they do not have money to pay for bail,” he says. “They are just suspected of doing crimes.”

Navotas City Jail, the most overcrowded facility of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) has a staggering congestion rate of 3,885 percent. A total of 932 inmates are packed into the jail built for just 23 people.

THE STENCH OF SWEAT AND HUMAN WASTE welcomes visitors to Navotas City Jail. The most congested jail in the Philippines, it's even norm for inmates not to sleep lying down.

Nine hundred thirty two inmates crowd into space built for only 23 people. Even the jail's hallways serve as a sleeping area just to fit the prisoners.

Senior Inspector Ricky Heart Pegalan, the warden of Navotas City Jail, says the United Nations standard is for each inmate to be given 4.7 square meters of space. With their jail's population, each prisoner is only given 0.20 square meters of space.

The inmates staying inside the jail are still waiting for the courts to resolve their cases, but their situation inside already seems like punishment.

Due to the scarcity of space in Navotas, 200 female inmates from there have had to live with 840 prisoners of Malabon City Jail Female Dormitory, which was built for 80 people.

Jona, a female inmate, has been in jail for 12 years while being tried for illegal recruitment. Her lack of knowledge of the justice system and insufficient funds to hire a private lawyer has contributed to the drawn out process.

Jona's case is far from unique among inmates in the Philippines. Of the 146,000 detainees of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology as of December 2017, only 2,732 have been sentenced, while 143,000 cases are still being tried.

Justice reform advocate and professor Raymund Narag sees the extended detention of the accused as the biggest issue leading to jail overcrowding. Shortages of public lawyers, judges, prosecutors, and courts also contribute to the delay in processing cases.

Narag estimates that jails are running at 600 percent overcapacity on average. This leads to other problems, including inadequate funds for food supplies and health necessities of inmates, not to mention jail guards to oversee the detention facilities.

Because of congestion, female inmates in Sta. Rosa City District Jail have resorted to condominium-type bed accommodations – sans the luxury and comfort, with prisoners boring large holes on the ceiling to create and have access to a top-level, makeshift floor.

THINGS AREN'T MUCH BETTER at Sta. Rosa District Jail in Laguna, where 160 female inmates are packed into a detention cell built for only 38 people.

The inmates occupy every space into which they can fit, even going under the wooden bunk beds just to find a place to sleep.

Linda, a woman with polio, has to crawl under the bunk beds to make it to her space at the farthest end.

Lola Nene, 74, and four other senior citizens who were arrested for allegedly pushing drug also suffer inside the congested detention cell.

Even the ceiling of the female dormitory has been turned into a makeshift floor. After boring holes in the ceiling to create and access an extra level, the inmates have to go down a ladder every time they need to take a bath or eat.

The barracks of the jail guards have also been turned into detention cells due to the increase of detainees. The facility has no infirmary or clinic to treat individuals, so ailing inmates are mixed with the rest of the population. Inmates with contagious ailments like tuberculosis are isolated, but their conditions aren't much better.

Mercy, who is emaciated because of her TB, stays on the bridge connecting the BJMP office and the facility, which has been improvised to serve as her infirmary. There is no nurse or medical personnel to attend to her.

Sometimes, inmates would contract deadly diseases without their knowledge.

"They would come in healthy, then they'd just die after they got out. They'd have no idea they had contracted tuberculosis while in jail," says Senior Inspector Shiela Olquino, warden of the jail's female dormitory.

This year, the Department of Health (DOH) has a P798 million budget to control the spread of TB throughout the country, which includes detention cells, where inmates are screened for the illness.

At the male dormitory, inmates with TB are placed inside the improvised infirmary on top of the stairs, with temporary railings that make it look like a bird cage.

Male senior citizens are also held in a separate detention cell.

Bed space, tarima in inmates’ parlance, is hard to come by at Bacoor City Jail, where guests’ receiving areas transform into multi-level sleeping quarters.

AN INMATE AT BACOOR DISTRICT JAIL in Cavite swears once he gets out, he'll never be in jail again. He just couldn't take the conditions in detention.

"As soon as the count ends, we'd lie down. We'd sit with a piece of cardboard to fan ourselves, because it's so hot. When I get out, I'll be a changed man. It's so hard here," he says.

Due to jail congestion, the visitors' area transforms into a sleeping area for inmates. Metal pipe frames and wooden boards are interlocked to form sleeping blocks over other inmates. Pieces of cardboard serve as hand fans. Rubber slippers double as pillows.

At the "basement" of the improvised sleeping facility, 42 inmates squeeze themselves.

The Bureau of Jail Management and Penology has a P14.5 billion budget in 2018, of which P1.5 billion is allocated for the construction of new facilities. But the allocation is intended only for new buildings in the National Capital Region, leaving the Bacoor District Jail out of luck.

The inmates have a simple request: electric fans so they could survive the heat and the cramped condition.

Superintendent Deogracias De Castro, the jail warden, promises that the request would be granted, over fear that the conditions may pose health risks to the inmates.

But that's about all the warden could grant. Other gripes, such as the quality of the food, may prove harder to address.

In 2016, the BJMP had a budget of P1.78 billion for food, but ended up spending some P1.82 billion, an excess of P40.35 million to feed inmates. In its report, the Commission on Audit noted that jail wardens had to resort to alternative means to feed inmates, opting to incur obligations from suppliers.

The same thing likely happened anew in 2017, when the BJMP had food budget allocation for only 106,280 inmates, even as the actual population surged to 146,302 by the end of 2017.

The government allocates P60 per day for food for each inmate, which is too small given the rising prices of commodities. The BJMP has been pushing to increase the budget to P150 to P200 a day.

Even transporting inmates to courts for their scheduled hearings is no easy feat. The two BJMP vehicles of the Cabanatuan District City Jail are designed to fit a total of 20 people, but are routinely stacked to carry some 50 inmates.

LIKE OTHER FACILITIES, Cabanatuan City District Jail in Nueva Ecija lacks space for its 768 inmates, who stay at a facility meant for only 81 people.

But the congestion extends even to the transportation, as the two Bureau of Jail Management and Penology vehicles, designed to fit a total of 20 people, are routinely stacked to carry some 50 inmates during trips to the courthouse.

The district jail occupies a whole hectare, giving inmates more room than at other facilities in the country. But the structure only occupies a small part of the land, which makes the heat and humidity — Nueva Ecija is one of the hottest places in the country — nearly intolerable for the inmates, who have to deal with the lack of ventilation.

Authorities have tried to mitigate the effect of the heat, putting free-flowing water inside the bathrooms and installing industrial exhaust systems to help inmates.

Another problem at the jail is the shortage in the supply of rice from the National Food Authority, which is ironic, considering Nueva Ecija is the country's rice granary. Having to buy commercial rice at higher prices leaves authorities with little budget to buy vegetables or other food ingredients.

Often, they would scrimp together rice given to detainees by their visitors, which they would mix in to supplement their daily allocation.

Of the 20 detainees of the Manila Police District this year, 13 have died in the crowded cells of MPD Station 3 in Quiapo. Difficulty breathing and infection have been the common reported causes of their deaths.

THE DETENTION CELLS at Manila Police District Station 3 in Quiapo are so congested that elderly and sick inmates are taken out of the cells, and simply handcuffed into bars outside them. The three cells in the station, built for 60 people, are overflowing with 173 inmates.

Of the 20 detainees of the Manila Police District this year, 13 have died in these crowded cells. Difficulty breathing and infection have been the common reported causes of their deaths.

Most of the inmates suffer from boils and other skin diseases which have spread all throughout the inmates inside the prison cell.

The crowding in jails has worsened over the past two years, since the start of the war on drugs that has been the centerpiece of President Rodrigo Duterte's administration. Over 45,000 have been arrested as drug suspects in Metro Manila.

But the arrests have far outpaced the speed by which prosecutors could file cases and courts could release commitment orders, leaving many detained in the cells of police stations.

Remigio Viceslao has been detained since May 4, 2018 for illegal gambling, a bailable offense. He says he doesn't even know the cost of bail. He claims he hasn't even had a hearing, more than two months after his arrest.

Boils, prickly heat and other skin diseases are common among detainees of the Quezon City Police District Station 4. Everyday, they are given 30 minutes to step out of their cell to receive sunlight and fresh air.

THE DETENTION FACILITIES of Quezon City Police District Station 4 have been in the headlines in recent weeks following the deaths of four detainees.

Skin disease due to severe congestion is also a major problem in the cell, where 81 inmates are squeezed into a facility meant to hold just 40.

Police have conducted medical check-ups for inmates who acquired boils, rashes, and other skin diseases.

Authorities have allowed detainees to go out of the cell for 30 minutes each day for them to breathe in fresh air as well as to have some physical activities.

The practice is part of the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners: "Every prisoner who is not employed in outdoor work shall have at least one hour of suitable exercise in the open air daily if the weather permits."

To try to further ease the suffering of detainees, the QCPD Station 4 also provided additional exhaust fans and industrial fans inside the jail cell. Others have also been transferred to police community precincts.

About 80 percent of the detainees are there due to drug-related cases, some of whom have been there for as long as three months.

Superintedent Rosell Cejas, QCPD Station 4 commander, sees it as an issue with the justice system. He says there's a need for constant liaisons with prosecutors and the courts for speedier issuances of commitment orders, so that releases, bails, and transfers to other jails can be expedited.

MOST INMATES HAVE ENCOUNTERED the consequences, sometimes fatal, of the slow justice system in the Philippines.

Domingo Cayosa, executive vice president of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP), says Philippine jail conditions are a microcosm of much bigger issues.

“It’s not only a reflection of the judicial system. It’s a reflection of our country,” he says.

“You have to look at how well a country’s government functions — the way they take care of the elderly, the poor, the jobless, its prisoners, the ones at the fringes of society,” Cayosa adds.

The slow grind of the wheels of justice have taken the toll on many lives, and the victims are often poor with little access to legal help, leaving them even more vulnerable.

MAGDALENA ESTINOR STILL RECALLS how her son Andrew was jailed in May 2011 for allegedly selling illegal drugs in Biñan, Laguna. After more than five years in jail, he was diagnosed with Pott's disease, a form of tuberculosis that affects the spine, inside the jail.

Andrew petitioned the court to allow him to seek medical care in the hospital.

"My son said, 'I'll die in our house, not in jail.' He was begging to get treatment, to be brought to the hospital," Magdalena says.

On May 25, 2017, Andrew's plea was finally granted. It was too late. He died a day later.

Magdalena laments it took too long before Andrew's plea was finally heard.

"It was extremely difficult for me, but what could I do when we didn't have money? There's no one to help," she says.

Retired Supreme Court Associate Justice Roberto Abad says the less fortunate are the usual victims of the delay in the justice system in the country.

"Delayed justice really hurts the poor more because the rich can pay for the inconvenience but the poor can't. And then they really suffer," Abad says.

MANUEL HAS BEEN BEHIND BARS since 2004 after being accused of kidnapping and frustrated murder. He laments the delay of the processing of his cases.

"I could not get back the time that was lost. My mother died, and my case still hasn't been resolved. It's always postponed," Manuel says, adding that in a year, there were only three to four hearings of his case.

Ronnie, for his part, was in Pasig City Jail for five years due to his robbery case. He was released from prison in 2016 after being acquitted.

"Nobody would believe me, even though I was right." Ronnie says.

He lost his job, his house, and even his family during his stint in jail.

"My family doesn't know, I was ashamed because I was there," he says.

Republic Act No. 8493 or the Speedy Trial Act of 1993 states that the trial of criminal cases must be finished within 180 days: "In no case shall the entire trial period exceed 180 days from the first day of trial."

"It has to improve. We have no choice but to have faith in the justice system. Otherwise, we take justice into our own hands, the accused would simply be killed," says Pacifico Agabin, former dean of the University of the Philippines College of Law.

Office repairs and upgrades for dilapidated courthouse facilities require patience in a developing country which allots less than one percent of its national budget to the entire judiciary.

PERHAPS A GRIM REMINDER of challenges facing the judiciary, the court house of the Bacolor Municipal Trial Court remains dilapidated for years after being inundated by volcanic mudflows in the 1990s. Documents and other important records have been destroyed in lahar, as well as the usual floods during rainy season.

Like most municipal trial courts, Bacolor MTC has suffered the consequences of the low budget of the judiciary branch of government in the Philippines. Office repairs and upgrades require patience in a developing country which allots less than one percent of its national budget to the entire judiciary.

Judge Lysander Montemayor says they already sought help from the local government to rehabilitate their justice hall. The request, however, needs endorsement from the Supreme Court.

"We only need the endorsement, the provincial government would fix it. We still haven't gotten it," Montemayor says.

Due to the lack of budget, some trial courts not only rent, but share their space with other offices. The Sta. Ana-Candaba Municipal Circuit Trial Court in Pampanga is located atop the municipal library. The Mexico Municipal Circuit Trial Court, also in Pampanga, sits above the public market.

According to the Supreme Court's Deputy Court Administrator Raul Villanueva, the judiciary does not own the property where most first-level courts are located. This is why the SC cannot simply provide a budget for their rehabilitation and repair.

The courts collect a Judiciary Development Fund from court fees from those who file cases, get married, seek copies of documents, and take bar exams. This amounted to P2.1 billion in 2017, but the bulk of this amount — 80 percent — are allocated for cost of living allowances for judiciary workers, with only 20 percent allocated for acquisition, maintenance, and repairs.

The government allots just P35.35 billion for the judiciary branch. Only a fourth of this is for capital outlays, including buildings.

"We've long been pushing for additional budget for the judiciary, considering that the judiciary is the third co-equal branch of government," says Midas Marquez, the SC's Court Administrator.

Villanueva adds: "What we're doing right now is asking Congress to give us some more financial or budgetary support. In the meantime we have to live with what we have."

Davao City Rep. Karlo Nograles, who chairs the Committee on Appropriations of the House of Representatives, says they only base the allotment for the judiciary on the submissions of the Department of Budget and Management.

"Every year, we increase the budget of the Supreme Court and the judiciary," he says.

Nograles adds: "Maybe if they're faster and more efficient maybe we might be able to increase even more."

But Budget Secretary Benjamin Diokno is cool to the idea of a substantial increase in funding for the judiciary.

"The government has many problems, not just the judiciary. I think it's better use of the funds that are given to them. They should look for better ways of utilizing it. This isn't our money. It's taxpayers' money," Diokno says.

Rowena Daroy-Morales, a professor at the University of the Philippines College of Law, sees no quick solution to the problem.

"The ideal, of course, is to have as much money as possible, so that all the courts would be beautiful and well-equipped and air-conditioned. That would be the dream. And that dream is slowly being realized, but it cannot be realized in one lump sum," she says.

But, she adds: "I really think it should have more."

Jails can be significantly decongested if inmates’ cases could be decided more quickly, but the courts’ 1.2-million caseload is shared by only 1,802 lower-court judges.

THE BURDEN ON THE JUSTICE SYSTEM is crystal-clear in Biñan, Laguna, where its two regional trial courts branches are faced with the gargantuan task of handling a combined 9,000-case backlog.

The two are among the top 10 courts in the country with the most cases, according to Supreme Court data as of September 2017. Aside from Biñan, the courts also handle cases in neighboring Cabuyao, whose court still doesn't have a judge, and Sta. Rosa, where the court has a new judge assigned, but still lacks a complete staff for full-fledged operations.

Teodoro Solis, executive judge of the Biñan regional trial court, notes that court hearings need full participation of multiple parties: prosecutors, lawyers from the Public Attorney’s Office, witnesses, arresting policemen, even the judge himself, and more. Proceedings are at risk of being rescheduled should one of them fail to show up during scheduled hearings.

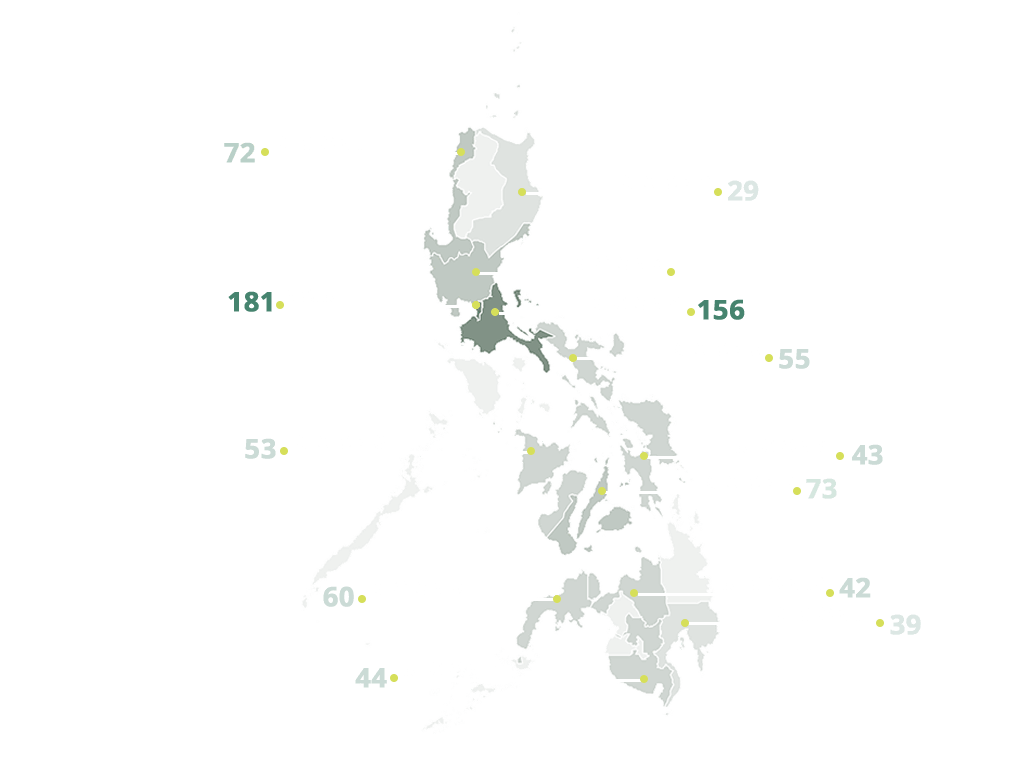

It's the same refrain across the country, where the courts face 1.2 million cases shared by only 1,802 lower-court judges.

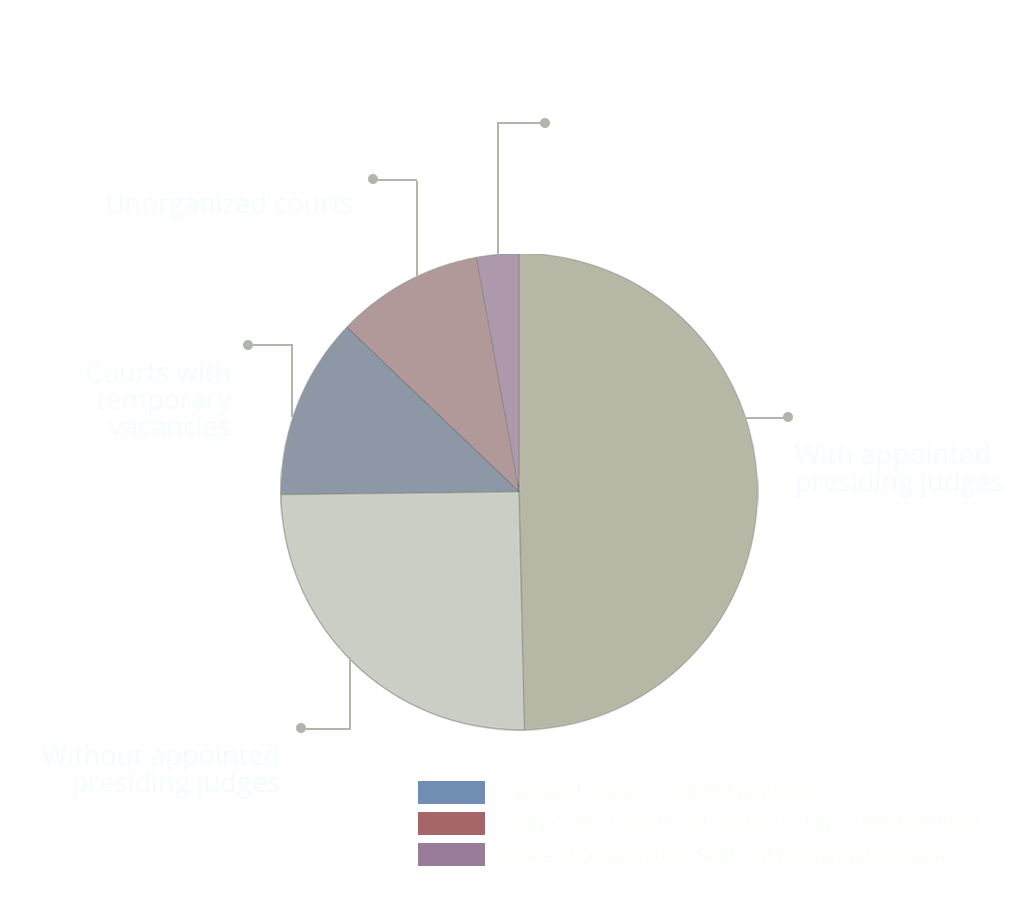

The problem is exacerbated by the fact that three of every 10 courts don't have judges.

Source: GMA News Research based on Supreme Court data, as of September 2017

The usual concern causing the perpetual vacancies in some areas: security.

Maria Milagros Fernan-Cayosa, the Integrated Bar of the Philippines' representative to the Judicial and Bar Council that screens candidates for judicial vacancies, says that there are plenty of applicants in urban areas like Metro Manila.

"But you also have the challenge of encouraging applicants to Tawi-Tawi, to Maguindanao, and I guess, you know, their concern is security," she says.

Source: GMA News Research based on Supreme Court data, as of September 2017

Unfilled positions plague not just chairs of the judges, but also the prosecutors.

According to Department of Justice data as of 2016, 34 percent of posts in the National Prosecution Service are vacant.

Each prosecutor is left to handle an average of 392 cases in court, according to Supreme Court and DOJ data.

For those who cannot afford private lawyers, the Public Attorney's Office (PAO) is mandated by the government to provide free legal aid.

But each PAO lawyer handles an average of 5,936 clients and 469 cases, which also affects their resolution, according to 2017 data.

"Sometimes it's true what they say, the rich get justice because they can afford attention and focus by a private lawyer," says Domingo Cayosa of the IBP.

The PAO also experiences a high turnover rate, with its lawyers resigning to move to positions in the private sector, in the NPS, in courts, and at government-owned and -controlled corporations.

ASIDE FROM THESE ISSUES, there are other ways courts could speed up trials, including the use of judicial affidavits for witnesses instead of direct testimony.

"Courts can really take a lot of shortcuts if they exercise wisdom — wisdom by finding out where justice and fairness lies directly. Go to the point right away," retired Supreme Court Associate Justice Roberto Abad says.

The problem has its roots in history, says former University of the Philippies College of Law Dean Pacifico Agabin, after the Philippines adopted the adversarial system from the Americans, which were meant for jury trials.

But because Philippine cases are not decided by jury, there are ways to speed up the process.

Both Agabin and Abad expressed belief that court dockets will be greatly eased with a shift in the Philippines’ trial system. Compared to the current adversarial system designed for jury proceedings, they say the inquisitorial system used in Europe moves much faster. In Europe, judges take the lead in establishing facts of the case, leading to speedier trials.

In the current system, Abad says: “A lot of delays are caused by objections.”

“The other party has to reply to the objection that will lead to a debate, then the judge makes a ruling. It is done all the time in the hearing,” he adds. “My suggestion is to, the judge will take note, and then proceed. The witness will answer despite the objection.”

While government tries to find answers and solutions to breathe new life to the judicial system, suffering inmates and their families have no choice but to wait, until justice is finally served.