We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

By the GMA NEWS SPECIAL ASSIGNMENTS TEAM with GMA NEWS RESEARCH

Reporting by DANO TINGCUNGCO, JP SORIANO, OSCAR OIDA, and RAFFY TIMA

Produced for the web by KAELA MALIG and JANNIELYN ANN BIGTAS

GMA News

January 10, 2019

Mary Grace was doing farm work in San Jose de Buan in Samar in 2007 when she accidentally fell off a carabao she was riding. But she wouldn't know until five years later just how bad her injury had gotten.

She fractured a total of nine bones in her back during the fall, and needed metal implant surgery. But she had no money, so not only was paying for the necessary operation out of the question, she could not even afford the regular checkups necessary to get to the nearest hospital more than two hours away.

“I’ve been bedridden because of injury for almost six years now,” Mary Grace says. “I am in so much pain, sometimes I think I should just kill myself because we couldn’t do it anymore. I’m stuck here. We couldn’t even go to the hospital because we couldn’t get a ride.”

It is an ordeal for residents of San Jose de Buan in Samar to get access to health care, with the nearest hospitals more than two hours away.

Seven patients have died in a span of three years: two mothers who died while giving birth, and five children, including two infants who died from severe pneumonia.

There are over 8,000 residents in San Jose de Buan, but the town does not have a single hospital. The town also has a community health center, but for people who need more serious medical attention, the nearest hospitals are two hours away in Catbalogan City and Tacloban City. Getting there isn’t quite so simple: the town's sole ambulance does not run, vehicles are seldom available, and the roads themselves leading to San Jose de Buan are hard to get through.

Giving them access to healthcare remains a challenge, according to Dr. Phoebe Cruz, the town’s municipal health officer. People live in remote locations across town, so the government makes do by sending doctors to the barrios to bring health interventions there.

That doesn't quite work for Barangay 3, where people have to climb not one, not two, but four mountains just to get from the town center.

Doctors have not visited the remote area for over two years now, though nurses and midwives have made an effort to conduct monthly checkups for residents.

A healthy person would need almost over four hours just to reach Barangay 3. The route becomes even more dangerous when it rains. If a person is extremely sick and is in dire need to get to the nearest hospital, the person would have to travel hours on end through mountains to get down to town, and then to Catbalogan.

Felicidad Labong, a resident at Sitio San Pedro, suffers from late-stage tuberculosis. She visited the doctor for the first time last May because her coughs never seemed to go away. After the checkup, she was hit with that dire diagnosis.

That first doctor visit turned out to be her last.

“I can’t walk properly anymore. I’m always just in my room. My body is already weak,” she says.

Knowing the dire situation in these areas, health workers try to offer help through prevention and warnings. Every month, community leaders have taken to updating the health workers on who have gotten sick, who are sick, and who need to be brought to the hospital.

“We organize it here, we talk about what services are needed and then we talk about how we can communicate with the barangay,” Cruz says.

The lack of access to health care has dire, even fatal consequences. In San Jose de Buan, seven patients have died in a span of three years: two mothers who died while giving birth, and five children, including two infants who died from severe pneumonia.

It’s an issue that’s not unique to San Jose de Buan.

“There are a lot of challenges. Doctors or nurses don’t really want to work in remote areas. Even the resources are very difficult to distribute, so it’s really up to the government,” says Dr. Rolando Enrique Domingo, an undersecretary of the DOH.

“It’s really hard to build a government hospital. One, there should be a very big investment and of course, we need a law because it needs to be in the budget every year.”

Because building new hospitals is not easy, the DOH has targeted bringing basic health care to remote areas, make access easier to hospitals for those in need, and increase the capacity of existing hospitals.

Bed capacity remains one of the biggest challenges for the government. The World Health Organization recommends that there should be one hospital bed for every 500 people — a target no single region in the country has reached.

The DOH has a more modest target of one hospital bed for every 800 people, but so far, the National Capital Region is the only area that has reached that ratio.

The Labuan Public Hospital has the lowest operations budget, based on GMA News Research's study of 60 DOH-funded hospitals in the country.

“Here when we use the X-ray, we have to turn off the air-conditioners in other departments just so we can operate,” says Joe Persada, the radiology technician.

To save the life of Atiil Otoali after a severe motorcycle accident, Dr. Waldo Mandai had to do an operation that went beyond the mandate of Labuan Public Hospital in Zamboanga

“He could’ve lost so much blood because it’s a fracture, bone was sticking out, and veins were cut,” says Mandai, the chief of the public hospital.

Because the Zamboanga City Medical Center was an hour away, the doctor had little choice but to go ahead with the operation

“There was no other choice because if we transferred him, he could’ve lost so much blood, he could’ve died. I said to have the operation here if we could,” he says.

Otoali still remembers the incident well. “Of course, I was scared. When I looked down I could see my bone, blood was coming out,” he says.

Despite the best efforts of its doctors, however, the Labuan Public Hospital could not answer all needs of its patients.

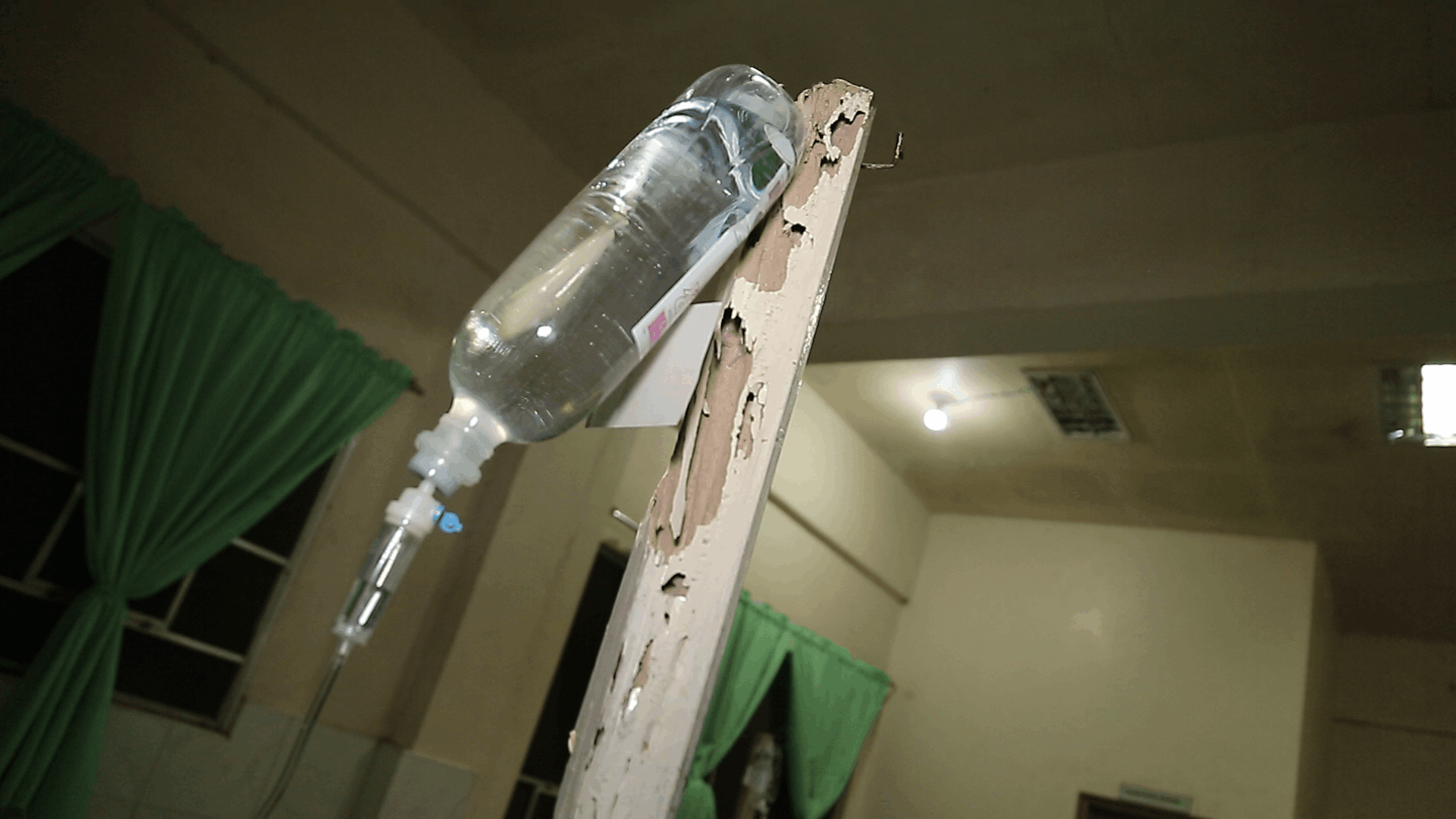

Labuan Public Hospital uses wooden stands to hold up IV bags when there is an influx of patients.

Marisa was due to give birth in a caesarean procedure, but because of a lack of capacity and equipment at the hospital, she had to be transferred to Zamboanga City Medical Center, some 33 kilometers away.

This meant a ride in Labuan Public Hospital’s only working ambulance, which also means she had to endure the broken air-conditioner along with the hot and bumpy ride.

Based on analysis by GMA News Research of more than 60 DOH-funded hospitals in the entire country, Labuan Public Hospital has the lowest operations budget. This, despite the hospital having to cater to 15 barangays in Zamboanga City and four other barangays in Zamboanga del Norte, serving a total of 270,000 people.

The hospital only has 38 workers on staff, and just 15 medical professionals: four doctors, seven nurses, four nursing attendants, and one midwife.

More than 20 patients are admitted into Labuan Public Hospital every day, which is a problem because there are only 10 beds in the hospital.

“If there are beds that are old... we repair those. We’d try to fit it among the patients. As long as you find a way,” Mandai says.

Health workers make do with improvised solutions. Wood is placed on beds so mattresses wouldn’t slip through. When there is a lack of IV stands, especially when there is an influx of patients, they use a wooden stand.

The hospital’s X-ray machine looks ancient, but that is not its only issue. Because of a lack of electricity supply, not all equipment in the hospital could run at the same time.

“Here when we use the X-ray, we have to turn off the air conditioners in other departments just so we can operate,” says Joe Persada, the radiology technician.

A bill to upgrade Labuan Public Hospital has already passed the bicameral conference committee of the Congress, which would make it a Level 2 general hospital with a 100-bed capacity.

But according to records, there is a long line of upgrades and bed capacity increases pending for over 70 other hospitals of the government. That means that Labuan Public Hospital may just have to wait its turn.

The Philippine Orthopedic Center is the only bone specialty hospital in the Philippines. But despite an increase in its operations budget for 2018 and additional funding under the Health Facilities Enhancement Program (HFEP) for the upgrade and maintenance of equipment, it still has among the lowest operations budget based on its bed capacity.

“I can’t take it anymore!” shouts 18-year-old Christopher “Tope” Oroños.

Tope has a bone illness, leaving his family with little choice but to seek treatment at the Philippine Orthopedic Center (POC), the only bone specialty hospital in the Philippines. His father Antonio could only watch as his son suffers.

“He’s really in pain. The pain never stops,” Antonio says.

Tope eventually receives temporary relief to get through the intense pain.

But the machine that would give him a free CT scan to identify the next steps for his treatment has been broken since May. Tope also needed another MRI scan, but the free service would not be available until after six weeks because of the long waiting list.

The POC has been home to patients in dire need of cheap or even free health services for over 70 years, and it shows.

“Because it’s free, a lot of people really go to us,” says Dr. Jose Brittanio Pujalte, Director of the Philippine Orthopedic Center.

According to GMA News Research, out of more than 60 DOH-funded hospitals, the POC has among the lowest operations budget based on its bed capacity.

Its operations budget for 2018 has increased from the previous year, and it received additional funding under the Health Facilities Enhancement Program (HFEP) for the upgrade and maintenance of equipment, but these have not been enough.

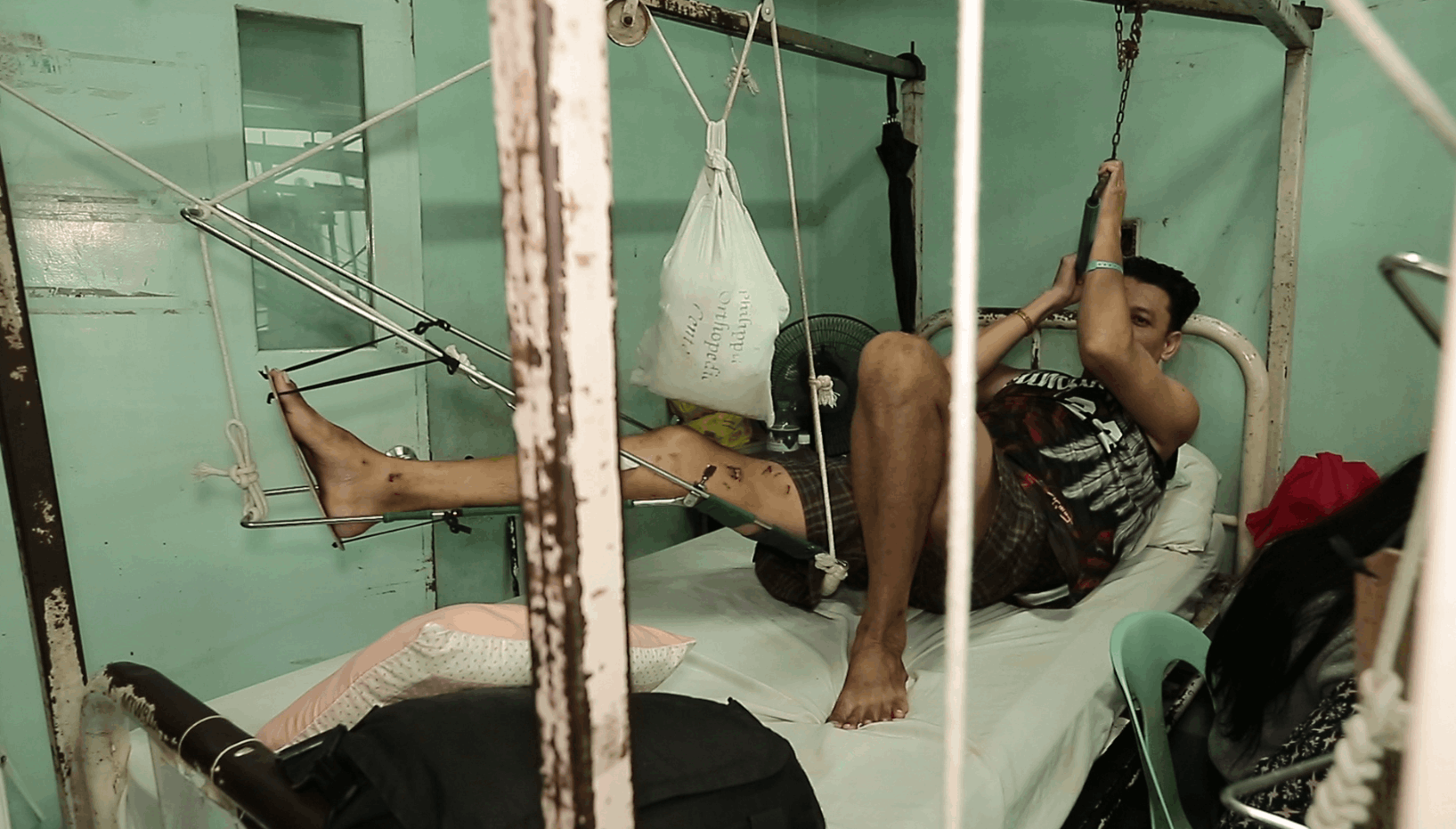

Health workers are forced to find resourceful ways to get by.

In the charity ward, for example, equipment that should be weighed down by metal use plastic bottles or cloth filled with sand instead. Pulleys that should have been thrown away are kept and reused.

“When we were about to condemn it, the aide saw that it’s actually still useful, so we just divided it and added rope,” says Rustica Pedro of the Nurse Traction Ward.

“If the person knows the concept of medicine, especially when it comes to the bone, the ideal or right equipment is not a hindrance,” Pujalte adds.

“What really goes well with the services of Orthopedic is the rehabilitation so we give them a chance to have rehabilitation services. And if we are blessed enough, we’d give them a place that is bigger so we can serve more.”

Aside from renovating the facilities, another solution would be the construction of another bone specialty hospital in different regions so that hospital congestion can be avoided.

“Of course, our resources aren’t unlimited. There are certain times we have to prioritize some equipment over others. If the following year, we won’t be able to get any, we’ll really have to divide the extra budget properly among the hospitals,” says Dr. Rolando Enrique Domingo, an undersecretary of the DOH.

Some patients cannot are forced to seek help somewhere else.

“We really had to rush, so I borrowed money so we can take him somewhere else because it’s really urgent. He really needs an operation immediately,” says Antonio, the father of Tope.

Despite all the efforts, Tope would pass away on October 29, 2018.

The government’s budget for the health sector has increased over the past several years, but took a P30 billion cut in the proposed 2019 budget. The budget of the DOH also suffered a P36 billion cut. But the issues plaguing the Philippine health care system go beyond these budget woes.

“If we were to give a diagnosis on the state of our health care system, we can still lower the expenses, and secondly, we can still fix how we give our services,” says Dr. Albert Domingo, a consultant for health systems strengthening of the World Health Organization (WHO) Philippines.

Out-of-pocket expenses of Filipinos for medicine, doctors, hospital and other medical services are higher compared to neighboring countries. This doesn’t count food, transportation, lost wages, and other expenses of relatives who take care of the sick in the hospital.

The problem always goes back to the limited funds.

“Not all expenses can be paid by PhilHealth, by DOH, by PCSO, or other departments that pay. Only the family of the patient is left to pay for these expenses,” says the WHO consultant.

According to the WHO, a stronger PhilHealth would not only give patients relief from financial burden, but it would allow the agency to have a say on the doctors and hospitals, and the quality of services they provide. The out-of-pockect expenses are a concern, the government admits.

“We want to remove out of pocket expenses and for financial protection. We really don’t want that every Filipino gets hospitalized, when they leave, they have to sell their houses, their carabaos, just so they can leave the hospital. We want to do it together, all our health finances so that when our patients leave the hospital, PhilHealth paid for it already, our finances paid for it, and the patient would leave without spending on anything,” says Dr. Rolando Enrique Domingo, the DOH undersecretary.

The government’s budget for the health sector has increased over the past several years, but took a P30 billion cut in the proposed 2019 budget. The budget of the DOH also suffered a P36 billion cut.

The Hospital Facilities Enhancement Program of the DOH, which is for the purchase and maintenance of medical equipment and the construction for old and new hospitals suffered the biggest blow. From P30 billion in 2018, the program got only a P50 million allocation this year.

“The Department of Budget and Management cites the ‘dismal spending performance’ of the Department of Health in the implementation of the HFEP as the main reason for the massive reduction in its budget allocation,” the DBM said in defending the cut.

The DOH undersecretary says this will mean that new procurement of high-end equipment for government hospitals will be put on hold.

“We have to fix the existing ones first. We still have ongoing procurement, and hopefully this will get us through tothe middle of the year,” he says. “The smaller equipment that the hospital needs, (they) will have to buy it themselves.”

WHO noted that politics can become an issue in the delivery of health care services. Of the 428 hospitals of the government, 337 or almost 80 percent are local government unit hospitals.

This becomes an issue because these hospitals could be affected by politics.

“One mayor would say, ‘Why would I help the governor? In the end people might say he or she is the reason why the system improved but I’m the one working.’ That kind of fragmentation, that kind of situation is what we’re trying to fix,” says Albert Domingo, the WHO Philippines consultant.

There is inequity in the distribution of medical services, according to the WHO. Doctors, health workers, medicine, and well-maintained facilities are often seen only at the urban centers, with those in remote areas lacking access to hospitals and health workers.

But Rolando Domingo, the DOH undersecretary, notes: “It’s also not cost-effective that in all the places we’ll build hospitals. For example, there’s only a small population, and then we’d build a 100-bed hospital, at every given time only 10 patients will be there and yet the expenses will continue on.”

The WHO Philippines consultant points out that facilities in remote areas would definitely need more government support.

“There is no profit when you go there. How will the salaries be paid for, the medicine? But that doesn’t mean that there is no responsibility to go there,” says WHO Philippines’ Domingo.

The DOH and WHO, though, agree on another key problem: patients prefer to go directly to big, specialty hospitals, which end up spending more on each patient compared to local health units. Lines become longer, equipment and facilities are overused, and doctors are overworked.

“Filipinos really got used to...They want that they go directly to specialists. It’s like they’re scared of small clinics or small hospitals. The truth is, most of their ailments could be healed by small clinics or small hospitals and it’s much cheaper,” says the DOH official.

Because of the cost to build a brand new hospital, the government wants to strengthen the system so that it will not only be easier to bring patients to the nearest hospital, but also bring them to the right hospital for their needs.

But there remains much work to be done: better roads, running ambulances, effective communication, delivery of medicine, referral systems to endorse patients to the right hospitals, whether government or private. All these depend on the cooperation of numerous officials and agencies of government.

The prescription is clear: to finally cure the Philippines’ health care system that has been ailing for far too long.

Share This Story