1957

Jesuit historian Father Horacio Dela Costa requested the 13th Air Force in San Francisco, California to repatriate the bells.

Adapted from the I-Witness episode

“BALANGIGA: A TALE OF TWO NATIONS”

by SANDRA AGUINALDO

Produced for the web by

KAELA MALIG and JESSICA BARTOLOME

GMA News

December 28, 2018

It was in the wee hours of the morning when the bells last spoke.

More than a century ago, when the sun had just peeked and families were still fast asleep, the sound of the bells suddenly thundered throughout the town of Balangiga in Eastern Samar.

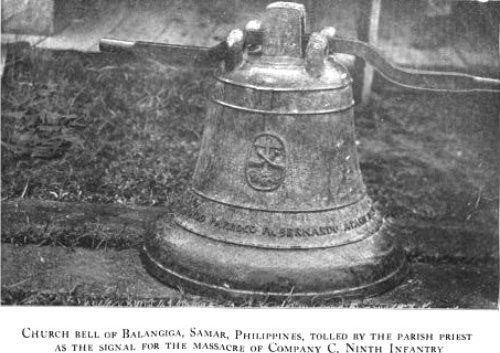

On the night of September 28, 1901, the three bells swung back and forth on top of the parish, telling the people, Go forth! and so the Filipinos did.

They charged from every direction toward American soldiers, relying on the sound of the bells as a signal to start one of the greatest Filipino victories in the Philippine-American war.

But if only things ended there. The Americans, mourning the lives they lost, came back with a vengeance, conducting one of the bloodiest massacres during the war between the two countries.

After their victory, they brought home with them their guns, their bullets, and the Balangiga bells.

But while the belfry fell silent, there was no way the people of Balangiga would allow the great tragedy to be forgotten, as they passed down tales from one generation to the next. Even to this day, the tales lived on, as if waiting for the return of the historic bells that gave voice to their ancestors’ spirit.

Full episode of “BALANGIGA: A TALE OF TWO NATIONS,” an I-Witness documentary by Sandra Aguinaldo.

Milagros Abanador-Cavales, 74, is the granddaughter of Valeriano Abanador, the police chief that led the battle against the Americans in Balangiga.

She heard the stories from her father, about how, to begin with, Americans had been welcomed by Filipinos with open arms, even though the foreigners had arrived while the Philippine-American War was raging in other parts of the country.

Soldiers from Company C, 9th Infantry Regimen arrived at Balangiga, Eastern Samar on August 11, 1901, according to historian Rolando Borrinaga, who has been studying the events surrounding Balangiga for 24 years.

“Basically for five weeks there was peaceful relations between the local residents and Company C. In fact, there was a lot friendship and fraternization,” Borrinaga says.

Some things, however, weren’t meant to last.

Boys who joined the Filipino army in 1898.

Photo: US Archives

Survivors of the Balangiga encounter, April 1902, Calbayog, Samar.

Photo: US Archives

Things came to a head when a woman selling sugarcanes was suddenly groped by two drunk Americans.

Hearing the woman scream, her two brothers came charging to rescue their sister, beating up the foreigners.

In response, the American captain called for a community assembly. In a flash, all Filipino men were ordered rounded up. A total of 143 were detained.

They were held overnight with no food and water. Finally, someone took pity on the young and the elderly, who were set free. But 80 detainees remained and were ordered to clean up the whole town.

Things only got worse for Filipinos from there. All bolos or any other sharp objects were confiscated.

There were even rumors that American soldiers tried to rape Filipino women. That seems to have been the final straw for Valeriano Amador.

“They weren’t successful in their rape attempts Valeriano and his men would do their rounds everyday,” his granddaughter Milagros says. “And always, Valeriano would hear the screams of the women and rescue them.”

Borrinaga notes there was one documented rape report against one American soldier, even though nothing came of it.

The Americans would order Filipinos to clean the entire town and cut down trees or anything that could possibly mask the approach of enemies. The residents themselves were accused of being part of the revolutionary government.

Nemencio Duran is a grandson of Vicente Candosas, who fought during the war. Two generations on, Nemencio remains familiar with the tales that drove Filipinos to revolt against the occupiers.

“The Americans destroyed our rice field. Anything we planted, they would destroy. The plantation, kamote plantation, were destroyed. The banana trees were cut down. The harvested rice were confiscated. The people said, ‘We will starve!’ So the police officers said, ‘Let us fight back.’”

That became the tipping point of the Filipino people, and after a series of secret meetings, a plan of action was set.

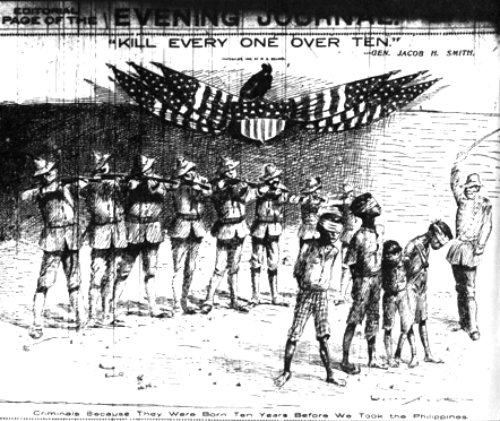

In 1901, during the Philippine-American war, American troops slaughtered thousands of residents above 10 years old in Balangiga, Samar. They also burned down the town's churches, taking with them the bells, which were from the Parish of Balangiga.

One bell ended up at an American Army base in South Korea, while the other two were sent to Camp D.A. Russell in Cheyenne. There they were displayed as part of a memorial to the 48 American troops killed by Filipino insurgents in 1901, which prompted the massacre.

President Rodrigo Duterte was not the first to demand the bells' return. Various individuals from different sectors sought to recover the bells since the late 1950s.

According to US envoy Sung Kim, their veterans believed that the war memorial should not be disturbed. In 1999, Congress passed legislation that made it unlawful to remove the two bells from the memorial on the base.

Duterte demanded the return of the Balangiga bells in July 2017. In October, Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana brought up the issue with his American counterpart, Secretary James Mattis, who then made it his personal mission to return the bells to the Philippines.

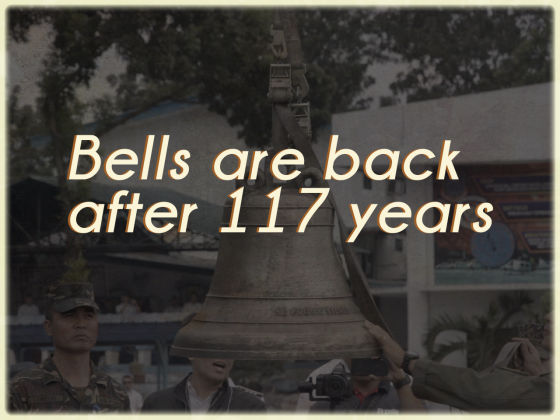

The bells arrived at the Villamor Air Base in Pasay City on December 11, 2018. It was briefly displayed at the Philippine Air Force Museum, before being returned to Eastern Samar.

It was around 6 in the morning when Valeriano Abanador made the first move, heading toward Private Adolf Gamlin, the American guard on duty, at the time.

At first glance, the fight didn’t seem fair; the American soldier had a gun, while the Filipino police captain only had an arnis cane.

But Valeriano Abanador was able to grab the rifle from Gamlin, who promptly fell. Abanador waved his arnis cane in the air, signaling to the person in the chapel to ring the bell.

And so, the Balangiga bells, atop the parish for everyone to hear, started to ring.

At that signal, Filipinos from all directions came charging, with their bolos in their hands and the bells still ringing at the background, toward American troops who were having breakfast.

Nemencio Duran says it was his grandfather Vicente Candosas who stood atop the church and rang the bells.

A group from another town called Quinapondan joined the uprising, charging from the forested area at the back of town.

An account by British journalist Bob Coutie says the American troops, many of whom were unarmed, were hacked down helplessly. Some were even allegedly mutilated, a point that Borrinaga, the Filipino historian, disputes. Filipinos have respect for the dead, he says, and would do no such thing.

Meanwhile, inside the church, a group of men were dressed up as women to disguise themselves before they attacked high-ranking soldiers who lived in the convent beside the church.

Joining the men was a woman who displayed courage during the hostilities. Casiona Nacionales, a hero of Balangiga, waved her rosary beads as a signal for the men to attack.

In one version of the story, the men even had a coffin that they used to hide their weapons. Valeriano Abanador supposedly told the Americans that they were having a fiesta, and got the Americans drunk on tuba. People brought their saints into the church in a procession, one of which could have been mistaken for a coffin.

In the end, 48 Americans died, while 16 to 28 Filipinos perished in battle. Twenty-two Americans were wounded while 26 fled using a boat on a nearby river.

This would come to be known as the greatest defeat of the Americans during the war.

The celebration would not last long. By October, the Americans would have their bloodiest revenge against the Filipino people.

General Jacob Smith infamously ordered his troops to turn the town into a howling wilderness and kill anyone above 10 years old — anyone capable of carrying firearms.

It was a ruthless massacre. Within a short amount of time, Balangiga was in ruins.

To this day, there is no data on how many Filipinos were killed during the massacre.

For the Americans, the most valuable spoils were the bells. They had been the signal for the Filipino people in revolt, symbolizing perfectly the courage and bravery of the overmatched people.

So with them came the Balangiga bells as their war trophy. For the next century, the Balangiga bells were heard no more in the province of Eastern Samar.

General Smith would later stand trial, not for murder or war crimes, but for conduct against the prejudice of good order and military discipline. His only punishment: being forced to retire.

Jesuit historian Father Horacio Dela Costa requested the 13th Air Force in San Francisco, California to repatriate the bells.

The Balangiga Historical Society petitioned the US Government for the return of the Balangiga Bells.

Then Philippine Defense Secretary Fidel V. Ramos and U.S. Defense Secretary Richard Cheney commenced negotiations for the bells’ return.

Then President Fidel Ramos met with then-US President Bill Clinton to ask for the return of the Bells. Instead of the Bells, Ramos came home with the nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Then Vice President Jejomar Binay urged the US to do an “act of goodwill” to its ally, the Philippines, by returning the bells, saying it would "further strengthen the longstanding diplomatic relationship" of the two countries.

In his second State of the Nation Address (SONA), President Rodrigo Duterte demanded from the United States the return of the bells.

The US Embassy in Manila vowed to solve the issue of the Balangiga bells.

US Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis notified Congress that the department plans to return the Bells of Balangiga to the Philippines.

In a turnover ceremony at the Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming, Mattis formally returned church bells to the Philippines. Philippine Ambassador to the United States Jose Manuel Romualdez was present during the ceremony.

The three Balangiga bells arrived at the Villamor Air Base in Pasay City around 10:30 a.m. on December 11.

The Balangiga bells have once again tolled for the first time in over a century, after Duterte rang one of them —and even kissed it — at a turnover ceremony in the Eastern Samar town. US Deputy Chief of Mission John C. Law handed over the bells' transfer certificate to Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana, who in turn handed the certificate to Balangiga Mayor Randy Graza.

It took 117 years for the Balangiga bells to find their way home.

“Many Filipinos and Americans worked tirelessly to make today possible. Since President Fidel Ramos first raised the issue of the bells with President Bill Clinton in 1993, virtually every Philippine president has pressed for the bells’ return,” said US Ambassador to the Philippines Sung Kim.

“President (Rodrigo) Duterte made a forceful appeal for the bells’ return during his 2017 (State of the Nation Address). I was there and heard his passionate call loud and clear.”

There was resistance from some veterans in the United States, because of fears that a return would taint the sacrifices of American troops who fought in the war. Retired navy captain Dennis Wright was key in convincing his fellow veterans to support the return of the bells to the Philippines.

Working tirelessly researchers and other veterans to raise awareness about the bells, they were able to secure the support of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) and the American Legion, two large groups of American veterans.

“So between a VFW and American Legion, they represent over four million veterans, American veterans. And those two resolutions became very powerful as a voice of the veteran community at large, not a minority in Shayan but a group at large said the bells should go home,” Wright said.

One obstacle remained: the National Defense Authorization Act prohibited the return of any “memorial object” for veterans.

“It was actually introduced in the year 2000. It was introduced at the time when nobody understood the bells’ history, didn’t understand Balangiga and the prohibition is pretty crafty. It didn’t say you can’t return the bells, it says you could not return something veterans memorial objects,” he said.

Working with Bellevue, Nebraska Mayor Rita Sanders, who is of Filipino descent, and their contacts in Congress, they pushed to change the law, finally allowing US Secretary of Defense James Mattis to certify that it was OK to return the bells.

There was celebration everywhere in the streets of Balangiga. People were laughing, smiling, and crying as Filipino soldiers finally unloaded the truck and delicately opened the wooden box that carried the bells, which the town had not seen in over a century.

Milagros, the granddaughter of Valeriano Abanador, could not help but break down in tears. The bells, she says, are not just a memorial for all Filipinos who died, but also a reminder of the courage it took to fight the Americans.

Thank you! Thank you! Thank you! people kept chanting as the bells made their way inside the St. Lawrence the Martyr Parish.

The last time the bells spoke, it said, Go forth! to the Filipino people.

Now, the bells will be back on top of the parish in Balangiga and their sound would be heard by Filipinos again. The Balangiga bells will finally be able to speak, We are home.

Share this story