We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

January 8, 2025

Cracked and calloused, 62-year-old farmer Angelo Vitalista’s hands tell a story of toil and survival.

For years, Vitalista has gotten used to dirtying his hands to plant rice and put food on the table.

But seeing his income from farming decline yearly prompted him to look for an alternative livelihood.

From plowing the field, the hands that used to produce the golden harvest are now picking up and selling other people’s junk and scraps to muddle through.

“Nagiisip na ako ng ibang hanapbuhay. Totoo po niyan ngayon ay nangangalakal ako. Mas kikita pa ako rito… sa bigas, naniyaniyamba na lang kami sa palay,” said the rice farmer from Barangay Telepatio in San Ildefonso, Bulacan.

(I am thinking of other ways to earn. Now, I collect and sell junk and scrap. I'm more certain of earning a profit this way. I only take a chance when I farm rice.)

Vitalista is among the rice farmers whose livelihoods have been affected by the enactment of Republic Act 11203 or the Rice Tariffication Law (RTL)—so much so that only more than 88,000 rice farmers were logged in the Registry System for Basic Sectors in Agriculture in the first half of 2024.

When the RSBSA registration was launched in 2020, the number of registered rice farmers was over 640,000.

The RTL removed the limits on rice importation, opening the country’s floodgates for cheaper varieties of the grain staple mostly from countries that subsidize their rice production.

Five years after RTL was signed, local Filipino farmers are facing stiff competition against the unimpeded arrival of imported rice which affected their income and changed the landscape of the country’s rice industry.

The law also polarized the rice farming community, with some benefiting from competitiveness support initiatives provided under the decree, while others were left behind, unaware of a state fund meant to help them compete with unlimited rice importation.

Rodolfo Alarcon, 77, raised the same sentiments about mounting losses from farming.

“Malaki po ang hinina (Our losses have been huge),” Alarcon said looking at his weathered hands, proof of the strenuous labor on the field.

A worker in a farmland in Barangay Sacdalan in San Miguel, Bulacan, Alarcon said he and his fellow farmhands had to endure the low farmgate prices of palay to sell their harvest.

The local rice needs to be competitive, they were told, which means prices should be at par if not lower than the imported ones.

Renato Galicia, a farmer in the same barangay, said Filipino farmers had always been at the losing end in the rice sector.

“‘Yun na nga ang nakakaapekto sa aming magsasaka eh, ang presyo ng bigas namin at palay, bumaba… Kaya kaming magsasaka halos wala nang kinikita,” Galicia said.

(That's what we face as farmers... The cost of our rice and palay went down. We almost have no profit.)

Ian Panganiban, a rice farmer and Barangay Telepatio’s councilman in charge of agriculture affairs in their community, said that in pre-RTL 2018, they negotiated favorable terms with rice traders and even saw gross returns double their capital.

“Sa singkwenta mil noon, nadodoble eh.. mga P100,000,” Panganiban said.

“Ngayon sa puhunan na P50,000 ang nabalik lang ay P25,000… lugi pa.”

(For a P50,000 capital before, it can double… to about P100,00. Now, for a capital of P50,000, the return is only P25,000… It’s such a loss.)

Vitalista, likewise, said that before RTL “maganda ang kinikita namin, nakangiti kami, nasisiyahan ang pamilya namin. Ngayon po ay talagang umaaray kami.

(We earned decently before, we smiled, and our families were happy. Now, the losses have been painful.)

Having experienced the same, Galicia said, “Halos wala nang kitain… kaya ang magsasaka ay hindi umaangat ang buhay. Kumbaga ay nakakaraos lang,” Galicia said.

(There's almost no profit at all… That’s why farmers can't improve their lives. They earn just enough to make ends meet.)

According to data from the House of Representatives Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department (CPBRD), the gross return from producing palay was at P79,670 per hectare against a production cost of P46,694 per hectare as of May.

This meant a profit of P32,976 per hectare in 2018 —the year before RTL was implemented.

When RTL took effect in 2019, rice farmers’ profits plummeted to P22,242 per hectare and plunged further to P19,680 per hectare in 2021.

Not only did the farmers lose money. Their purchasing power weakened as well.

Signed during the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte, RA No. 11203 or the RTL allowed the unhampered importation of rice, replacing quantitative restrictions on importing the grain with tariffs —35% if imported from among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries, 40% if within the minimum access volume (MAV) of 350,000 metric tons (MT) coming from outside the ASEAN.

The National Economic Development Authority said that by removing quantitative restrictions, the government addressed both the needs of consumers for a lower retail price of rice and provided more aid to farmers through the excess tariff revenues.

The RTL also established the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF), an annual appropriation of P10 billion provided for six years starting in 2019.

The fund was to provide farm machinery and equipment, credit assistance, seed development, and training to increase local rice farmers’ yield and competitiveness.

Perhaps the most immediate impact of the RTL can be seen in the dramatic drop in the farmgate price of palay or unmilled rice.

Data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) showed that the farmgate price of palay had been fluctuating post-RTL from an average of P21.25 per kilo in 2019 down to P18.85 per kilo in 2020.

Palay’s farmgate price rose to P20.17 per kilo in 2020 but dropped to P18.54 per kilo in 2021. In 2023, it went up to P21.71 a kilo, but still lower than pre-RTL 2018 when the farmgate price stood at P24.38 per kilo.

“Malaki ang hinina kasi masyadong mababa ang naging presyo ng palay namin kung ikukumpara noong nakaraan,” Galicia said.

(Our revenues went down significantly because the price of our palay dropped compared to previous years.)

Vitalista recalled that shortly after RTL was passed, the farmgate price of palay plunged dramatically.

“Bumaba ang presyo ng palay. Halos limang piso ang binaba (The price of palay dropped by almost P5.)

Eulogio Federizo, chairman of Santor Bongabon Agriculture Cooperative in Nueva Ecija, recalled the drop in the price of palay but adverted to the benefits of the RCEF.

“The good thing is [nang] nagkaroon ng Tariffication Law… nanganak, nagkaroon ‘yung RCEF,” Federizo said.

(The good thing is when the Tariffication Law was passed, the RCEF was introduced.)

The RCEF is divided into four key programs: namely rice farm mechanization (P5 billion), seed propagation (P3 billion), rice credit assistance (P1 billion), and extension services (P1 billion).

Santor Bongabon Agriculture Cooperative is among the beneficiaries of the Philippine Center for Postharvest Development and Mechanization’s (PhilMech) farm mechanization initiative.

"May mechanical grinder na binigay galing sa PhilMech at DA (Department of Agriculture),” Federizo said.

(We have a mechanical grinder from PhilMech and the DA.)

The PhilMech is the implementing agency for the RCEF’s farm mechanization component. The program gets the bulk 50% or P5 billion of the annual P10 billion RCEF.

Data from PhilMech showed that it distributed 28,294 machinery and equipment from 2019 up to the first half of 2024, or 95.41% of the 29,655 it procured during the period.

PhilMech chief science research specialist May Ville Castro said the RCEF’s farm mechanization initiatives have helped decrease the cost of labor in producing rice.

“Na-decrease natin ang labor cost by P2 per kilogram. This is equivalent to P9,000 per hectare na dagdag income ng farmers na gumamit ng facilities or technologies na galing ng RCEF,” Castro said.

(We decreased the labor cost by P2 per kilogram. This is equivalent to P9,000 per hectare in additional income for farmers who used facilities or technologies provided by the RCEF.)

The PhilMech research specialist added that mechanization also resulted in aversion of losses in palay harvesting of around 31,000 metric tons (MT).

“That’s equivalent to more than P5 million per annum kung iko-convert sa peso,” Castro said.

(That's equivalent to more than P5 million per annum if converted to peso.)

Unfortunately, small farmers in Barangay Sacdalan, San Miguel, Bulacan, who are not part of any organized group or cooperative seem to have been left behind as far as the RCEF and the programs and assistance it offered were concerned.

“Wala kaming naramdamang epekto sa 'min eh, hindi naman nakarating sa amin... Nababalitaan lang namin, hindi namin naramdaman dito… hindi bumaba dito sa amin,” Galicia said.

(We don't feel its effects, the aid does not reach us... We just learned about it in the news, we don't feel it... It does not reach us.)

Nardo Castro, also a farmer in San Miguel town, said he only felt the government’s assistance in times of natural calamities such as strong typhoons.

“‘Pagka lang may baha… Walang assistance ‘pag walang calamity,” Castro said.

(It's just when there's a flood... there's no assistance if there's no calamity.)

Doro Vitalista, the chairman of Barangay Telepatio, said farmers in his community didn't get farm machinery and equipment from the government.

“Wala, hindi pa kami napagkakalooban ng traktora," the barangay leader said.

(None, we have not been provided with tractors)

Panganiban, a councilman in Telepatio, added that the government’s farm mechanization programs prioritized big farm cooperatives and associations.

Rice watch group Bantay Bigas chairperson Cathy Estavillo criticized the lack of government subsidy for local rice farmers to be able to compete with cheaper imported rice.

“Hindi kayang makipag-compete sa mga imported na bigas ng mga exporting countries na fully government-subsidized ang production,” Estavillo said, adding that the P10-billion RCEF is a “very insignificant amount para maging competitive ang ating farmers.”

(Local rice farmers cannot compete with the imported rice from countries whose production is fully subsidized by their governments.)

“Tama ang sentiments ng mga magsasaka… Ang machineries kasi mga members lang ng farmers coop ang nakatatanggap…,” she said,

(The sentiments of some farmers are correct. The machineries are only provided to those who are part of cooperatives.)

Asked about the supposed disproportion of the government's aid to local farmers, Department of Agriculture spokesperson Assistant Secretary Arnel de Mesa told GMA News Online that the DA would look into this matter and check on which program the concerned farmers could be enlisted.

"We'll check 'yung ganoong perception, nevertheless kasi 'yung implementation natin ng RCEF, this is for about 57 provinces nationwide. Hindi naman kasi lahat ng probinsya ay mayroong RCEF kasi ang focus ng RCEF 'yung tinatawag natin na implementation ng inbred seeds," he explained.

(We'll check that perception, nevertheless, the implementation of RCEF is for about 57 provinces nationwide. Not all provinces have RCEF because its focus is on the use of inbred seeds.)

"We just have to know who they are and if indeed they are not being reached by the program, we just have to enlist them," De Mesa added.

De Mesa further acknowledged that among the challenges met by the government in distributing assistance was the Philippines' geographical characteristic. However, he guaranteed that measures were being implemented so that giving out aid to farmers would not be affected.

"Of course 'yung ano, ang bansa kasi natin geographically isolated 'yan eh, 'yung ibang areas so 'yan 'yung distribution issues natin... that's why we are now using 'yung tinatawag na interventions monitoring card o use ng mga e-vouchers para 'yung mga card na iniissue kahit malayo 'yung mga farmer, malapit sa kanya 'yung mga accredited fertilizer, pupuntahan na lang niya and then 'yung pera na puwede niya makuha, nakalagay na rin doon sa card so malelessen 'yung interaction at less prone to any procurement or corruption issue," he said.

(Of course, our country is geographically isolated so we have distribution issues. That's why we are using intervention monitoring card or e-vouchers so that even the farmers are in far-flung areas, the accredited fertilizers are near him and then he will just go there to get the cash assistance, it's also in the card so it would be less prone to any procurement or corruption issue.)

Combining lower farmgate prices of palay and lack of government assistance to support their livelihoods, Galicia said that some farmers were forced to sell the lands they tilled.

Galicia, who is among the 176 farmers in Barangay Sacdalan, admitted that he would be forced to do the same if losses would continue to outweigh their profits in farming.

“Malapit-lapit na siguro kung talagang puro lugi, iiba na lang ng pagkakakitaan... Kasi ang nangyari nga 'yung Tariffication Law na 'yan maraming nagbenta ng sakahan… gawa nga nang bumaba ang palay na inaani nila. Wala nang nangyayari kaya napipilitan silang ibenta na lang,” he added.

(I would be forced to do so if there's no profit. What happened was after the enactment of the Tariffication Law, a lot of farmers sold their lands because the [price] of palay went down. Nothing was happening so they were forced to sell their lands.)

Vitalista also said that he is now in the process of selling his rice farm.

“Ako ay isa sa mga nagpupursige na mabenta ang aking dalawang ektarya kasi nga wala naman kinikita,” Vitalista said.

(I’m really bent on selling my two hectares because it’s no longer profitable, anyway.)

Data from the DA's Registry System for Basic Sectors in Agriculture (RSBSA) showed that registered rice farmers are gradually declining.

Post-RTL in 2020, the year when RSBSA registration was launched, the number of registered rice farmers was 640,508. In 2021, it went up to 1,434,661, but went down to 390,783 in 2022 and further decreased to 247,247 in 2023.

As of the first half of 2024, there are 88,438 rice farmers registered in the RSBSA, data showed.

As regards the size of rice fields that have been harvested, the number is consistently within four million hectares from 2019 until 2023. In the first half of 2024, the area harvested for rice stood at 2,065,231.33 hectares.

Nevertheless, since the RTL took effect in 2019, palay production has been consistently growing above 19 million metric tons (MT).

Latest data from the Philippine Rice Research Institute indicated that palay production stood at 18.81 million MT in 2019 and grew to 19.29 million MT in 2020. It further went up to 19.96 million in 2021 until it moderated to 19.76 million MT in 2022.

In 2023, palay production hit a record high of 20.6 million MT, an increase of 1.5% on a year-on-year basis.

However, in the first six months of 2024, palay production declined 5.5% to 8.53 million MT from 9.05 million MT in the same period last year.

In terms of yield, the national average yield grew to 4.05 MT per hectare in 2019 from 3.97 MT per hectare in pre-RTL 2018.

Last year, yield grew to 4.17 MT per hectare — the highest since the rice trade liberalization law was implemented.

While local production grows, the country’s importation of rice also follows.

From 1.857 million MT imported grains in 2019, the Philippines’ importation of rice has consistently grown to 2.099 million MT in 2020, 2.771 million MT in 2021, 3.826 million MT in 2022, and 3.606 million MT in 2023.

From January to August 2024, the country has so far imported a total of 2.804 million MT of rice.

PSA data showed that the share of imports in the country’s total rice supply had been increasing.

At the onset of RTL’s implementation in 2019, the share of imported rice to the total rice supply stood at 20.2%, up from 13.8% in 2018 pre-liberalization regime.

It went down to 15% in 2020, but increased to a peak of 23% of the total rice supply in 2022.

The Philippines has been consistently among the top, if not the top, rice importers in the world.

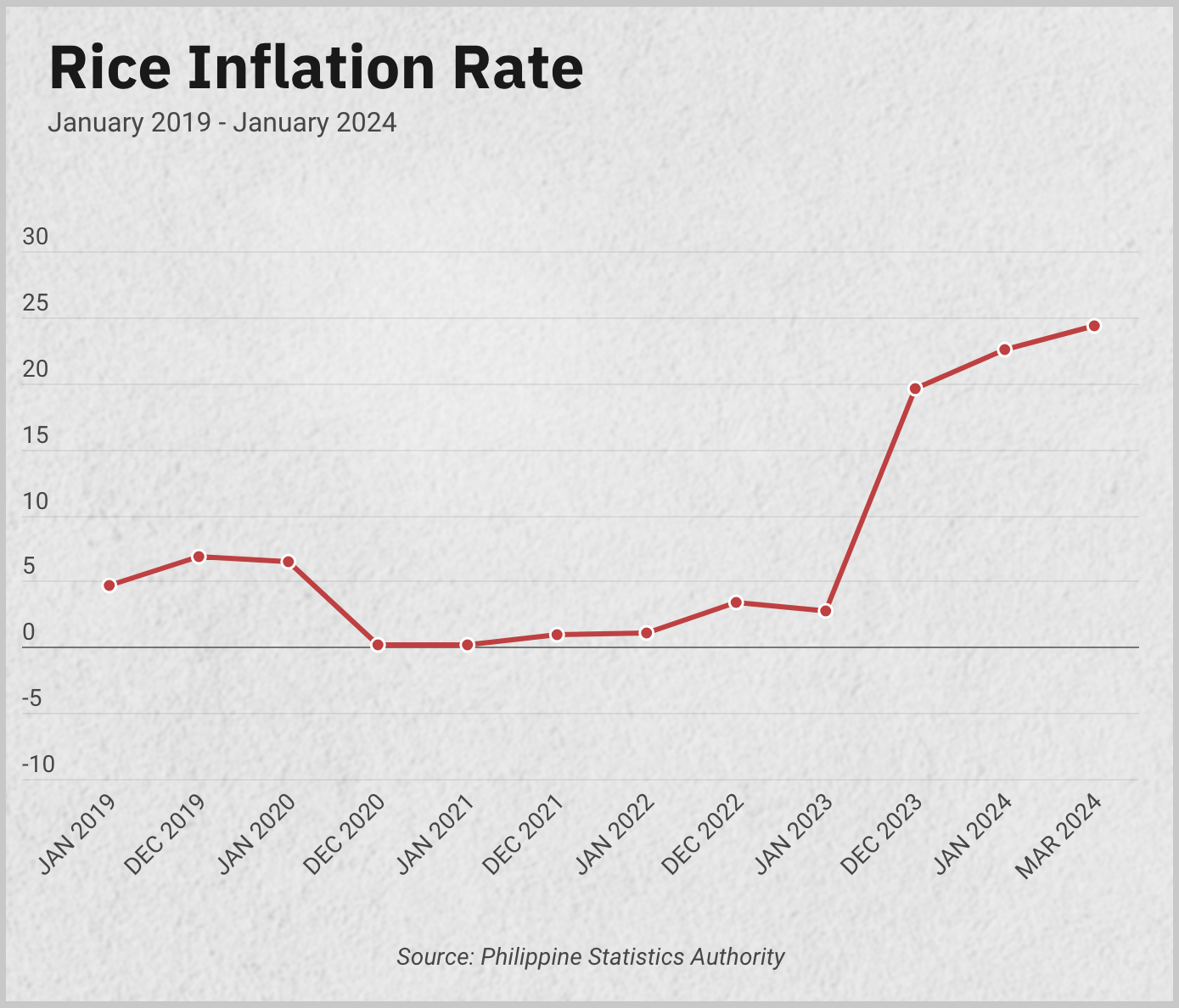

The enactment of RTL in 2019 was prompted to address the surging inflation of rice price seen in the last quarter of 2018 when the rice stocks of the National Food Authority (NFA) dwindled.

According to the CPBRD, citing data from the PSA, the price of rice has remained relatively stable from 2020 to 2022.

It began climbing starting August 2023, right after the start of Russia's invasion of Ukraine which disrupted global supply chains.

In March 2024, rice inflation spiked by 24.4% —its highest in 15 years, according to the PSA.

At the start of the second half of this year, early signs of stabilizing rice prices were already observed as rice inflation dropped to a single digit in September 2024 after trailing within high double digits since late last year.

Rice inflation slowed down to 5.7% in September this year, from 14.7% in August, thanks to combined base effects and the impact of reduced tariff rates for the imported grain.

In June 2024, Executive Order No. 62 was issued by President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., directing the reduction in the tariff rate for imported rice to 15% from 35%.

Apart from addressing rice inflation, the enactment of RTL —which amended the Agricultural Tariffication Act of 1996– was in compliance with the country’s commitment to the World Trade Organization (WTO) to replace all quantitative restrictions on agricultural products when it joined the WTO in 1995.

The Philippines tariffied other agricultural products but exempted rice, which is a highly political commodity as it is the country’s main staple.

Since 2005, the country has repeatedly requested the WTO for an extension of quantitative restrictions on rice until the final extension was granted in 2017.

To fully comply with the commitment to the WTO, the Philippines harmonized its domestic policies with its international commitment, thus the passage of RA 11203.

The DA has been supportive of amending the RTL as the agency's intention was premised on how it could intervene in the market during times when rice prices climb to an all-time high as well as during conditions like El Niño when rice production is gravely affected.

"Actually, 'yung House version ng amended RTL captured mainly 'yung mga wishes ng Department of Agriculture," De Mesa said.

(The House version captures the wishes of the Department of Agriculture.)

"Ang nakalagay sa amended law in cases na mayroong emergencies or situation that would warrant na either the DA or NFA will have the opportunity to intervene kung masyadong mataas ang presyo... kagaya ng nangyari noong mga nakalipas na panahon o kulang talaga 'yung supply. We need to intervene," he added.

(In the amended law, cases of emergencies would warrant either the DA or NFA to intervene if the price of rice is too high... just like what happened in the past or when there was insufficiency in supply. We need to intervene.)

Meanwhile, Samahang Industriya ng Agrikultura (SINAG) executive director Jayson Cainglet said the problem with the RTL was in the logistics aspect of the distribution of farm machinery to farmer-beneficiaries.

“Although may problema sa pag-distribute ng makinarya, pero logistics ang problema diyan hindi ‘yung batas,’’ Cainglet said.

(Although there's a problem in the distribution of machinery, logistics is the main problem and not the law itself.)

The current RTL has removed the NFA’s authority to import and sell cheaper rice in the retail market and replaced its mandate to buffer stocking during emergencies.

For NFA acting administrator Larry Lacson, the grains agency’s market intervention should be brought back.

“I believe that bringing back the marketing intervention mandate of NFA will be beneficial for the Filipino people as it will provide checks for possible manipulative pricing,” Lacson said, adding that “it will also be good for the NFA as it will result in better cash flow to finance the operations of NFA as a GOCC.”

Barangay Sacdalan farmer Castro is also seeking the return of the NFA’s market intervention function.

“Buhayin ulit ang NFA at yung proseso at pamamahala ng [importasiyon],” Castro said.

(Revive the NFA’s powers and its function of overseeing the importation.)

Likewise, Bantay Bigas’ Estavillo said the NFA’s mandate to intervene in the market should be returned and called for the total abolition of RA 11203.

“Para maibalik ang mandate ng NFA to regulate ang presyo ng bigas kailangan ibasura ang RA 11203,” Estavillo said.

(To bring back the mandate of the NFA to regulate the price of rice, RA 11203 should be scrapped.)

For SINAG’s Cainglet, the NFA should remain as a buffer stocking agency and “let the private sector do its thing.”

In December 2024, President Ferdinand “Bongbong" Marcos Jr. signed into law the measure extending the life of RCEF, with the aim to provide better support for the country’s farmers.

Republic Act No. 120278 or the Amendments to Agricultural Tariffication Act pushes for greater support for local farmers from the government through the provision of farm machinery and equipment, free distribution of high quality inbred certified seeds, and other interventions.

Under the new law, a rise in the annual allocation to the RCEF will be instituted, from the current P10 billion to P30 billion until 2031.

The expansion of the annual allocation will pave the way for new initiatives such as soil health improvement, pest and disease management, the establishment of solar-powered irrigation systems and small water-impounding projects, as well as the distribution of composting facilities for biodegradable wastes.

This law will also strengthen the Department of Agriculture’s regulatory functions by creating and maintaining a database to monitor the country’s rice reserves.

According to Agriculture Secretary Francisco Tiu Laurel, the increased funding to enhance the rice industry’s competitiveness will certainly boost both rice yields and farm output.

When it comes to the NFA’s mandate, the law allows the said office to sell rice buffer stocks to government agencies and the public, through KADIWA ng Pangulo centers, in areas that are experiencing rice supply shortages or extraordinary price increases.

It also permits the replenishment of NFA rice buffer stocks with either locally produced or imported rice in case of insufficient supply of locally produced rice.

According to Cainglet, SINAG is among the agricultural groups that are supportive of the P30 billion appropriation to aid more local farmers.

For Galicia, it would be better if the government would just focus on improving productivity as he pointed out that the Philippines is an agricultural country.

He said the country did not need to import, saying it had the capability to produce for the local demand.

“Pagukulan na lang ng pansin 'yung inaani natin dito, marami tayong ani eh... sa totoo lang eh... maluwang ang pinagaanihan natin. Ngayon, bakit kailangan pa natin kumuha ng import eh samantalang kaya naman natin?" Galicia said.

(Just focus on our local produce, we have lots of yields... we have lands. Now, why do we need to import if we can produce our own?)

Vitalista, like the other Bulacan farmers, said they longed for the day when they could work fulltime in the farm and make harvest that could not only feed his family, but the community.

But they said farmers need not just dole-outs or even agricultural inputs, but the kind of support that would benefit them in the long run and make them competitive in this increasingly borderless economy.

Training, access to technology and better logistics systems are essential – and yes, policies and laws that would shape a food economy that ensures that farming can also mean making a decent living. —with web design by Jessica Bartolome/LDF/NB/RSJ, GMA Integrated News