We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

Located along the typhoon belt and the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Philippines is hit by an average of 20 tropical cyclones every year.

In recent years, these weather disturbances were aggravated by climate change, along with other extreme conditions such as droughts, heat waves and floods, according to a 2023 World Meteorological Organization report.

The perennial challenge for the Philippine government regarding climate adaptation and mitigation remains: ensuring the security and safety of all Filipinos, especially during times of disasters.

For years, urban and rural communities across the country have resorted to transforming schools, churches, basketball courts, even cockpits, and similar public spaces into makeshift evacuation centers. These structures are not built for disaster response, yet these are repeatedly tapped by the government during times of urgent, recurring need.

The Department of Education (DepEd) recently raised concern anew regarding the use of schools as evacuation centers, saying this results in learning disruptions among students.

Experts have suggested the construction of permanent evacuation centers—typhoon and earthquake-resilient infrastructure which readily addresses the well-being of all evacuees, including children, women, persons with disability, and the elderly.

For this special series, GMA News Online made repeated and sustained requests for interviews with the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) and the Quezon City Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office (QC DRRMO), but neither of them obliged.

In Part 1 of the series, GMA News Online looks into the current state of evacuation centers in the country, the high-risk locations of multiple centers in Metro Manila, and tales from evacuees who sought solace, but failed to find it.

Nenita Macasero still remembers what her family endured when they relocated to an evacuation center in July as Typhoon Carina and the Southwest Monsoon (Habagat) wrought havoc on their community in Barangay Bagong Silangan, Quezon City.

“Walang pagkain. Maraming tao. Walang matulugan, agawan (No food. A lot of people. No place to sleep. People had to fight for their sleeping spaces),” recalled Nenita, a grandmother.

She even remembers the air—hot, humid, and smelly—as the center was bursting at the seams with evacuees.

Residents from other flooded areas were also brought in because they had nowhere else to go.

Nenita Macasero, a grandmother, was evacuated during the height of Typhoon Carina and the Southwest Monsoon in July 2024. She had her share of struggles at her temporary safe haven at the Bagong Silangan Evacuation Center, which was jampacked with other evacuees.

JAMIL SANTOS

Barangay Bagong Silangan is situated near the San Mateo-Marikina River, where settlements are located at the lower section of a steep slope. Much of the barangay’s land area is at medium to high risk of flooding, based on the hazard map of the University of the Philippines (UP) Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards (NOAH) project.

Nenita’s home in Tagumpay Village is no stranger to evacuations and flooding. In the case of Carina, floods persisted even after the impact of the typhoon.

Images of raging floodwaters on the barangay streets and Tagumpay Village made the rounds on social media, and so did the cramped spaces at the temporary evacuation center.

Nenita, with her daughter, son-in-law, and grandchildren in tow, eventually decided to leave their flooded house under the care of her husband, and took her daughter and grandchildren to the Bagong Silangan Evacuation Center, where they stayed for the next three days.

“Maayos ang pasilidad kaso nga lang, sa dami lang ng tao, nahihirapan na rin… Masaya na magulo. Maingay. Maraming bata kasi, tapos may mga senior pa. Tapos ‘yung mga CR pa sa ano, iba-iba ang amoy… Siksikan, agawan,” she shared.

(The facility was okay but we inevitably had problems because there were too many people… It was chaotic, especially since there were a lot of children. It was fun, yet chaotic. It was loud, because there were a lot of kids, and there were seniors, too. The bathrooms had all sorts of smells… It was cramped and you had to fight over the space.)

Residents of Tagumpay Village in Barangay Bagong Silangan wade through flood waters brought about by Typhoon Carina. Some of them are seen in the right photo at the area's primary evacuation center, which has a capacity of 5,000.

VIRGIE PENSOY

Barangay Bagong Silangan has a population of about 160,000, yet its primary evacuation center can only accommodate 5,000 individuals according to Wilfredo Cara, the incumbent barangay captain who is now on his final term.

It used to be a covered basketball court before construction began in 2021. It is now a five-storey permanent evacuation center.

For many years, the barangay had to rely extensively on its elementary and high school facilities to provide shelter during disasters. Today, however, they still do.

The Bagong Silangan Elementary School and Bagong Silangan High School service displaced residents who could no longer be accommodated at the permanent evacuation facility.

A check on the two school campuses at the UP NOAH map show that both are situated at high-risk flood areas.

Cara said residents can turn to about 15 evacuation sites in the barangay, including schools and churches, but these are simply not enough as they get hit by floods as well.

“Nahihirapan kami 'pag sabay-sabay na. Hindi namin mari-rescue ‘yan nang sabay-sabay,” Cara said, recalling the barangay’s experience during Super Typhoon Carina last July.

(We have a hard time responding when they seek help at the same time. We are not able to rescue or accommodate them all at once.)

The mammoth floods during the onslaught of Tropical Storm Ondoy in 2009 left a painful lesson to Bagong Silangan residents as 36 were killed and 100 were reported missing in the area.

Cara said it became clear to everyone, including those in higher government offices, that early response and action during potential calamities are nonnegotiables.

The Marikina River, which has a long history of overflowing during heavy rains in Metro Manila, is seen from roofdeck of the Bagong Silangan Evacuation Center.

JISELLE ANNE CASUCIAN

Wilma Rosal, principal of the Bagong Silangan Elementary School, had to juggle her responsibilities of operating a temporary evacuation center and managing the opening of School Year 2024 to 2025—both in the same week.

While over 9,300 elementary students went back to school, an estimated 5,000 evacuees sought shelter at the same campus.

Almost 40 rooms were made available for evacuees who could not be accommodated at the Barangay Bagong Silangan Evacuation Center amid the effects of Typhoon Carina and the Southwest Monsoon (Habagat).

“Kung makita niyo sila, naku. Maaawa rin kayo… [They were experiencing] mixed emotion[s]. 'Yung nandiyan 'yung kaba nila na ano na nangyari 'yung naiwan nilang gamit. [Gusto nila…] 'Yun bang makakain lang muna sila at makatulog lang muna roon sa hindi muna basa.” —Wilma Rosal, principal of the Bagong Silangan Elementary School on the state of evacuees during Typhoon Carina

Serving as the principal of a public school comes with the responsibility of leading an evacuation center, Rosal said. It is part of her job to “understand,” she added.

One of things she learned was that for evacuees, the rule is always “survival of the fittest.”

“Kung makita niyo sila, naku. Maaawa rin kayo… [They were experiencing] mixed emotion[s]. 'Yung nandiyan 'yung kaba nila na ano na nangyari 'yung naiwan nilang gamit. [Gusto nila…] 'Yun bang makakain lang muna sila at makatulog lang muna roon sa hindi muna basa,” Rosal shared.

(If you only saw them, then you would pity them, too… [They were experiencing] mixed emotion[s]. They felt scared about what would happen to the things they left behind… They just wanted to have a meal and sleep on a dry surface.)

Rosal’s expanded job responsibilities, so to speak, gave her eye-openers about issues and solutions related to disaster response and recovery—the most pressing of which relates to infrastructure and what she calls “discipline.”

If given a choice, Rosal said, Bagong Silangan Elementary School should no longer serve as an evacuation center during recurring times of disaster.

She echoed the call of the Department of Education (DepEd) to do away with the practice as it disrupts the learning of Filipino school pupils.

Schools, churches, basketball courts, and multipurpose halls across the country are not intended to accommodate internally displaced persons (IDPs) during the rainy season, yet many of these have been serving this purpose for decades.

In a 2019 study titled "Evaluation of the Spatial Distribution of Evacuation Centers in Metro Manila, Philippines," researchers observed that the location of evacuation centers (ECs) is not determined by factors that address disaster risk reduction and management, such as safety from flooding and earthquakes, but on the availability of existing facilities.

The research team was composed of postgraduate students, some of whom have already graduated, at the Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology in the University of the Philippines (UP). For bibliographic purposes, the author is identified as E.P. Cajucom. Dr. Cherry Ringor was their professor and is a collaborator in the research.

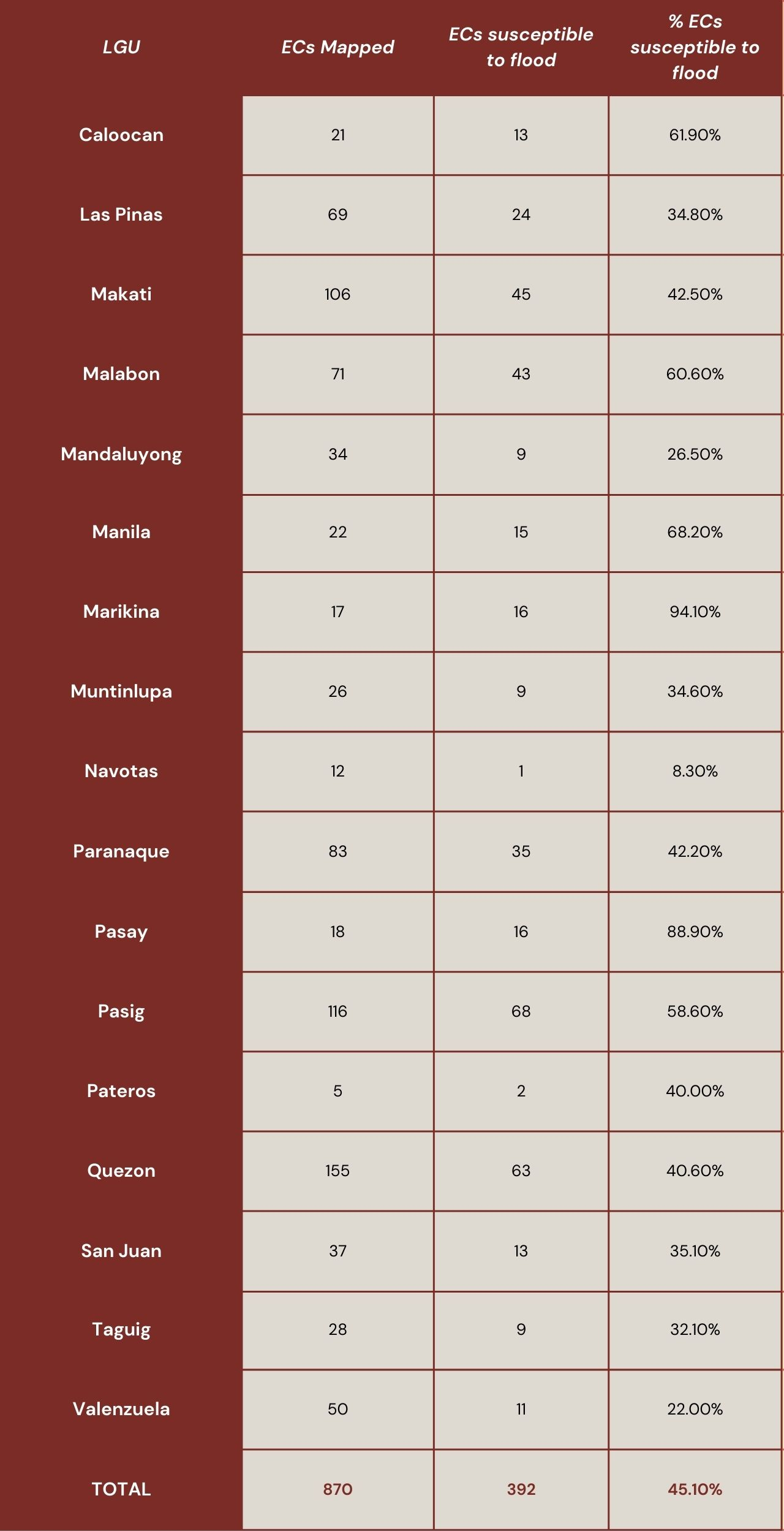

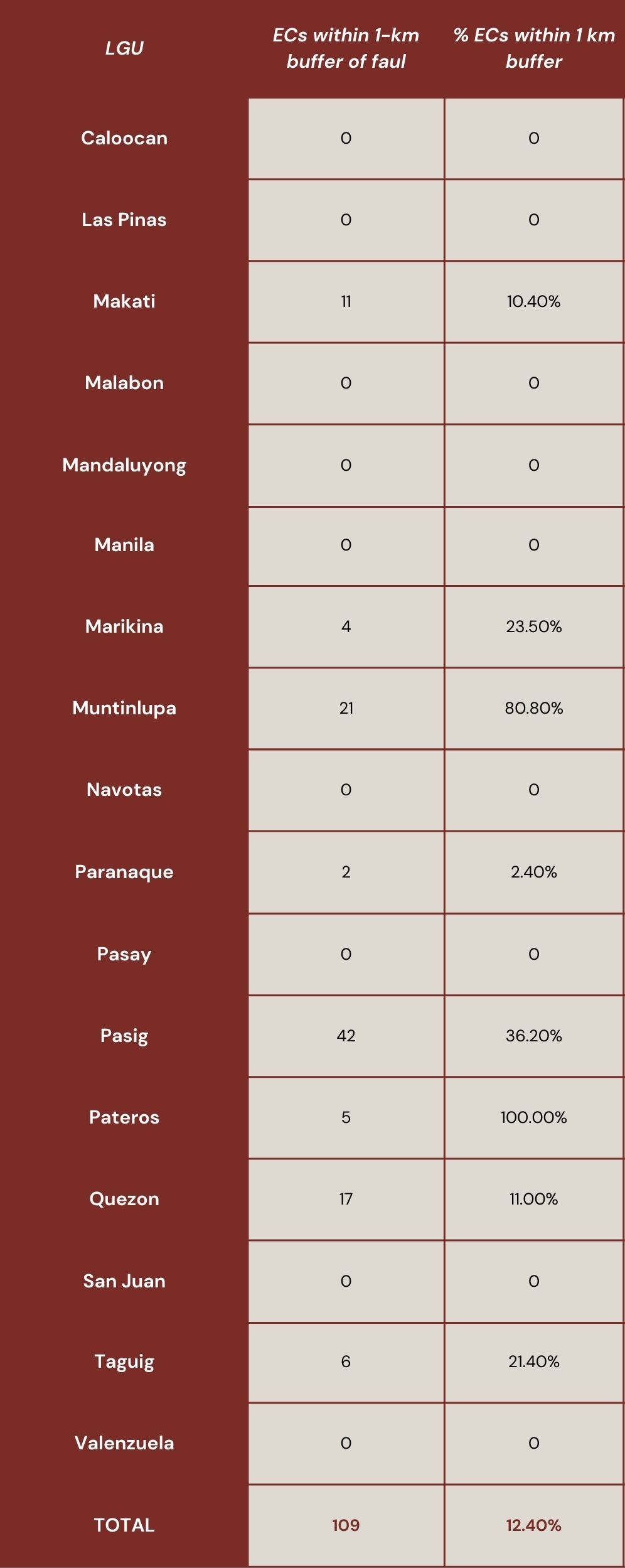

Source: Study by University of the Philippines Diliman Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology post-graduate students (2019), "Evaluation of the Spatial Distribution of Evacuation Centers in Metro Manila, Philippines"

The study found that out of 392 mapped evacuation centers (ECs) in Metro Manila, 45% were “situated in flood-prone areas,” while 12% were “within the 1-km buffer hazard zone of the active West Valley faultline.”

The cities of Marikina and Pasay were found to have greater than 80% of their evacuation centers within a flood hazard zone, while the cities of Caloocan, Malabon, Manila, and Pasig have greater than 50% but less than 80% of evacuation centers within a flood hazard zone.

Navotas, which has had its own battles with flooding over the years, was “at the bottom of the list” as only 1 of its 12 evacuation centers, or 8.3%, was located in flood-prone areas.

"As a risk reduction measure, evacuation centers which are identified to be susceptible to flood and/or earthquake need to be evaluated in terms of [their] location,” the study said.

It added, “The construction of ECs must also conform to the Philippines’ National Building Code, i.e. withstand strong winds (300 km/hr) and earthquakes that can register 8.0 M on the Richter scale. Responding to this mandate would require long-term planning and logistics.”

Source: Study by University of the Philippines Diliman Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology post-graduate students (2019), "Evaluation of the Spatial Distribution of Evacuation Centers in Metro Manila, Philippines"

The study also pointed out that congestion in evacuation centers was a “common scenario” during disasters, leading to other complications.

It recommended a ratio of 1.5 square meters of floor area per person for short-term occupancy, and a ratio of 3.5 square meters per person for long-term occupancy to minimize adverse effects on the evacuees’ health and well-being.

“Insufficient health and sanitation facilities in the designated ECs complicate the problem of congestion and increase the vulnerability of evacuees to post-typhoon diseases,” the study read.

Meanwhile, a study by Greenpeace Philippines in March 2023 titled, “Building resilient communities: Promoting people participation to address disaster risk,” reported that the use of temporary shelters raises concerns for “space, privacy, and safety” of evacuees.

Rosal echoed this concern, saying crimes and inappropriate behavior were committed by and among affected residents in the Bagong Silangan Elementary School during the evacuation for Typhoon Carina.

Amid the disruption of disaster response operations to the lives of displaced families, Rosal said some couples had sexual intercourse while other people were inside the elementary classrooms.

The situation deteriorates, Rosal said, from lack of discipline and privacy resulting from the evacuation.

“Ma-lecture din sila na dapat 'pag nandiyan, wala 'yung ‘labing-labing.’ 'Yung kunwari eh, 'yung mag-asawa nagtatabi, nakikita ng mga ibang mga evacuees na ‘yun. Naggagawa pa sila ng mga love-making,” Rosal said.

(They should be lectured that when they are there, there should be no moments of intimacy. For example, if a couple lies down together, other evacuees can see that. They even do love-making.)

Rosal has avoided opening some classrooms for fear of looting, after items were either lost or damaged in several areas after accommodating displaced residents.

“Mayroon din 'yung walang pakialam [na evacuees], kinalkal pa 'yung mga gamit ng mga teachers. Kinuha pa kahit 'yung mga coins-coins lang, pati ball pen, 'yung mga crayons… Mayroon pa 'yung mga instances na nabasag ang TV [dahil] kahit 'pag sabihin natin na, [huwag] munang bubuksan kasi baka kikidlat, pagkatalikod mo, isaksak nila talaga 'yung TV,” she added.

(There are also [evacuees] who don’t care, and would even sift through the items of teachers. They even took coins, ballpens, crayons… There were also instances where the TV broke [because] even if they were told [not to] open the TV because there might be lightning, they would plug it in as soon as you turn your back.)

Bagong Silangan Elementary School (shown here) and the Bagong Silangan High School have been serving as temporary evacuation centers sometimes even while classes are held, just as they did in July 2024 amid the onslaught of Typhoon Carina and the Southwest Monsoon.

JAMIL SANTOS

The Child-centered Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Action Primer published by UNICEF in 2022 reported that stress, particularly economic stress, and lack of security in evacuation centers often lead to the dangers of abuse, violence and exploitation during disasters, as well as mental stress for child evacuees.

“[Children and young people] face the risk of being sexually harassed, raped, sold or traded, put to work and prostituted… [They] may also experience mental health problems because of the death or illness of family members, separation from parents or guardians, neglect and even class disruptions,” the study read.

"I don't think we are on the right track. Simple answer. Why? Because we did not learn from Tacloban... If you underestimate the hazard, then all of your efforts will be based on that–underestimated din. And that’s when it turns into a disaster."

—Mahar Lagmay, geologist and executive director of the University of the Philippines (UP) Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards (NOAH) project

A 2023 study titled “Philippine Evacuation Center through the Children's Lens” by Maria Talitha Borines detailing the experiences and recommendations of children after staying in evacuation centers also noted that separation from their families, overcrowding, and lack of privacy affect their emotional and overall wellbeing.

Borines’ study found that children were burdened with several negative feelings during their stay at one evacuation center in a flood-prone barangay, namely: afraid, happy, sad, pity, difficult, frustrated, and hungry.

In terms of relationships, the study said "the neighbors were arguing" was the cited experience of some of the respondents, due to the lack of space in the classroom.

"Moreover, when they queue for relief goods, stress and anxiety are the typical reactions of people after a disastrous event," the study observed.

As thousands of Filipinos pack evacuation centers in yet another storm season, geologist Mahar Lagmay, executive director of the University of the Philippines (UP) Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards (NOAH) project, noted that the country still has yet to learn its lessons from previous disasters.

“I don't think we are on the right track. Simple answer. Why? Because we did not learn from Tacloban,” Lagmay said in an interview with GMA News Online, emphasizing the devastating effects of Super Typhoon Yolanda in 2013.

In the final report by the National Disaster and Risk Reduction Management Council (NDRRMC), Yolanda left 6,300 dead, most of whom passed away due to drowning and trauma.

Of the 3.4 million families displaced nationwide due to Yolanda, only 90,972 families stayed in evacuation centers.

“The hazard maps that serve as our basis for evacuation and action, the response to the imminent threat, were based on storm surge hazard maps that were severely underestimated,” Lagmay said.

If only closer attention was given to the science-based warnings indicated on these maps, Lagmay said, then more lives could have been saved.

“Seventy percent of the evacuation centers in Tacloban were inundated by storm surges. Ang daming namatay doon. So, kung ‘yung mga sumunod na alam ang gagawin, sumunod sa protocol [at lumikas sa evacuation centers], ay namatay, what more doon sa mga hindi sumunod?” said Lagmay.

(Seventy percent of the evacuation centers in Tacloban were inundated by storm surges. So many people died there. So, if the other people that followed knew what to do, followed the protocol [and relocated to evacuation centers], also died, what more can we expect about the safety of the people who didn’t?)

According to Lagmay, many of the current evacuation centers in the Philippines are located in areas that are safe from a regular storm surge, but did not account for large- scale flooding or other hazards.

“Scientists from all over the world [said that], our problem about hydrometeorological hazards, including storm surges, would be bigger than before,” he said.

Lagmay added, “This is what I was talking about, that we did not learn from our lesson [from] Yolanda. It’s all about citing everything about disaster risk reduction [and] response is anchored on the profile, is anchored on the anticipatory plans of the community. If you underestimate the hazard, then all of your efforts will be based on that–underestimated din. And that’s when it turns into a disaster.”

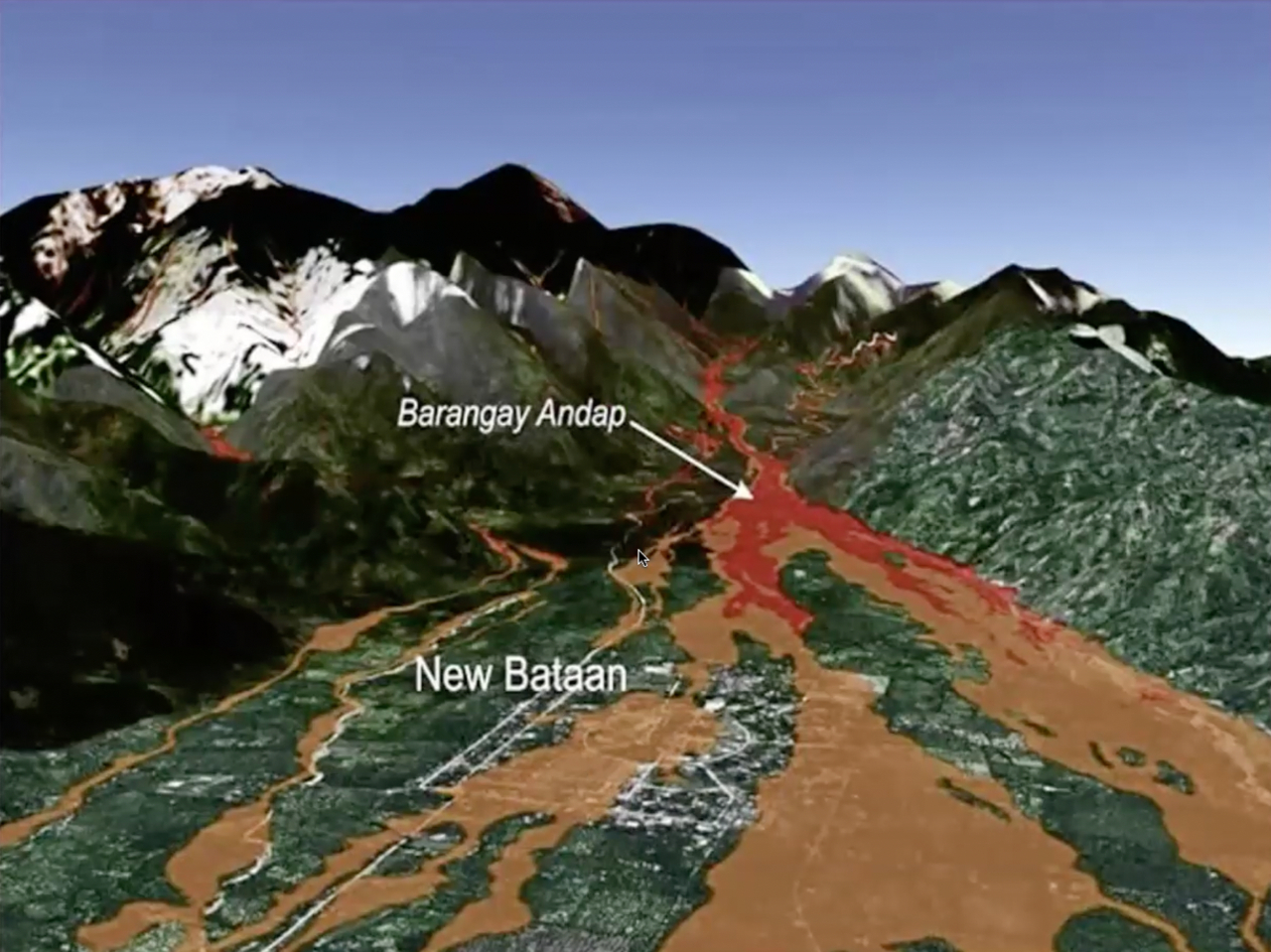

In the first photo, a science-based deterministic map shows the landslide risk areas in New Bataan, Compostela Valley. Amid the wrath of Typhoon Pablo in 2012, hundreds of residents died at an evacuation center in Barangay Andap, indicated here as within the path of the landslide flows. Right photo shows some of the huge rocks that came crashing down in New Bataan at the time.

UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES RESILIENCE INSTITUTE

The UP NOAH chief also cited the evacuation centers in New Bataan, Compostela Valley, which were unable to provide safe haven to evacuees during the wrath of Typhoon Pablo in 2012.

Over 500 people in New Bataan reportedly died, mostly due to debris flow that reached several meters high. In Barangay Andap, several residents passed away after taking refuge in evacuation centers, but these were later devastated by flash floods.

Lagmay lamented that deterministic maps—which are based on historical anecdotes and interviews—continue to be used in planning disaster response and in determining the locations of evacuation centers. This was also the case in Barangay Andap, Lagmay said.

“Ang daming namatay diyan sa evacuation center na ‘yan. (There were a lot of people who died in that evacuation center.) Why were they brought there? It’s because we had a map [that was] single-scenario. Worst case, according to the people, generated from anecdotal accounts and expert opinion, na iyong Barangay Andap has low susceptibility to landslide,” he said.

“Dumaan ‘yung bagyo na Pablo, dala-dala ‘yung tubig, dala-dala ‘yung mga bato [sa katabing ilog] ... When it flowed into that area, natabunan ‘yung buong lugar by several meters, (the area was buried by several meters.)” he shared.

(When Super Typhoon Pablo came, it was carrying water and rocks from the adjacent river. When it flowed into that area, the entire area was buried by several meters [of debris.])

Lagmay said communities have yet to use probabilistic maps—based on scientific data to predict where risks may occur—to consider all hazards in their planning and disaster response.

“We have not changed our methodologies for the creation of hazard maps that are used by communities to plan their response, their evacuation centers, and to plan their development. That is the status,” Lagmay said.

The overall responsibility of developing a comprehensive framework for handling “all hazards, mutli-sectoral, inter-agency and community based approach” lies with the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), as mandated by Republic Act (RA) 10121.

The NDRRMC has yet to provide comments to issues raised in this series despite repeated requests from GMA News Online.

"As a risk reduction measure, evacuation centers which are identified to be susceptible to flood and/or earthquake need to be evaluated in terms of [their] location."

—"Evaluation of the Spatial Distribution of Evacuation Centers in Metro Manila, Philippines" (2019), a study by University of the Philippines Diliman Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology post-graduate students

Under Section 6 (k) of the law, the NDRRMC is tasked to develop coordination mechanisms “for a more coherent implementation of disaster risk reduction and management policies and programs by sectoral agencies and LGUs.”

The NDRRMC shall also direct the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) to conduct periodic assessment and performance monitoring of the member-agencies of the NDRRMC, and the Regional Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Councils (RDRRMCs).

Further, the DRRMOs and barangay-level councils must maintain a database of human resource, equipment, directories, and location of critical infrastructure and their capacities such as hospitals and evacuation centers.

Meanwhile, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), in support of the NDRRM Framework, is tasked to “increase disaster resilience of infrastructure systems” and “develop and implement comprehensive preparedness and response policies, plans and systems.”

The DPWH shall also ensure that built structures are climate change-resilient.

Thus, included in DPWH’s menu of projects are “disaster prevention, mitigation, and preparedness projects,” among which is the construction of “permanent evacuation center[s].”

The facade of the Bagong Silangan High School, which has been used as a temporary evacuation center for years even with the construction of a larger permanent facility.

JAMIL SANTOS

Today, the use of temporary shelters are permitted by law–but with limitations.

Republic Act 10821 or “An Act Mandating the Provision of Emergency Relief and Protection for Children Before, During, and After Disasters and Other Emergency Situations” instructs the LGUs to “establish and identify safe locations as evacuation centers for children and families.”

Under the act, the National Housing Authority (NHA) shall coordinate with the DSWD, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG), and LGUs of the areas declared under a state of calamity to “immediately establish an option for transitional shelters, prioritizing vulnerable and marginalized groups including orphaned, separated, and unaccompanied children, and pregnant and lactating mothers.”

Section 5 of RA 10821 provides that “Only in cases where there is no other available place or structure which can be used as a general evacuation center may a school or child development center be used as an evacuation center.”

Equipping communities with permanent evacuation centers, the UP study recommended, is a critical step towards building a long-term solution for disaster resiliency.

“While most, if not all, of the identified ECs are makeshift shelters which are government buildings or public spaces (i.e. schools, barangay halls, gymnasiums, etc.) by design, it is recommended that future construction and development of additional ECs be based on the DILG guidelines and that location identification be based on spatial distribution and capacity requirements,” the study said.

The UP study emphasized that setting up evacuation centers (ECs) in appropriate locations not only ensures the safety of evacuees but their overall well-being.

“Proper location of ECs, considering population density of an area and analyzing flood and earthquake susceptibility, not only help solve the problem of congestion but also reduces the risk of loss of lives and damage to property,” the study said.

A resident walks along a street at Tagumpay Village (left photo) under a rainy, yet calmer, sky. Tagumpay, a Filipino word for success, faces a slew of challenges every year as it rests on a steep slope leading to the Marikina River, making it vulnerable to flooding.

JISELLE ANNE CASUCIAN

Under the law, gymnasiums, learning and activity centers, auditoriums and other open spaces shall be utilized first when a school or child development center is used as an evacuation center.

“Classrooms shall only be used as a last resort. The use of the school premises shall be as brief as possible,” it stated.

The last resort, however, seems to be a common theme–year in and year out–in providing evacuation centers for Filipinos during times of calamities.

While the law allows this, stakeholders such as principal Rosal continue to hope that this practice would soon change. This would not only ensure that the children’s right to a proper education is protected, but that evacuees forced to flee their homes are truly out of harm’s way.

“How I wish that someday… I am praying to the Lord na someday, sana ang paaralan ay talagang paaralan lang na hindi na magamit sana ng evacuees, (that someday, schools will remain schools and will no longer be used by evacuees.)” she said.

However, with the current state of evacuation centers and disaster response in the Philippines, Rosal’s dream still has a long way to go before turning into reality. —VDV/RSJ, GMA Integrated News