We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

With the threat of the La Niña phenomenon looming on the horizon, the agricultural sector braces for more rains and floods even if it has yet to recover from the wrath of the El Niño and recent tropical cyclones.

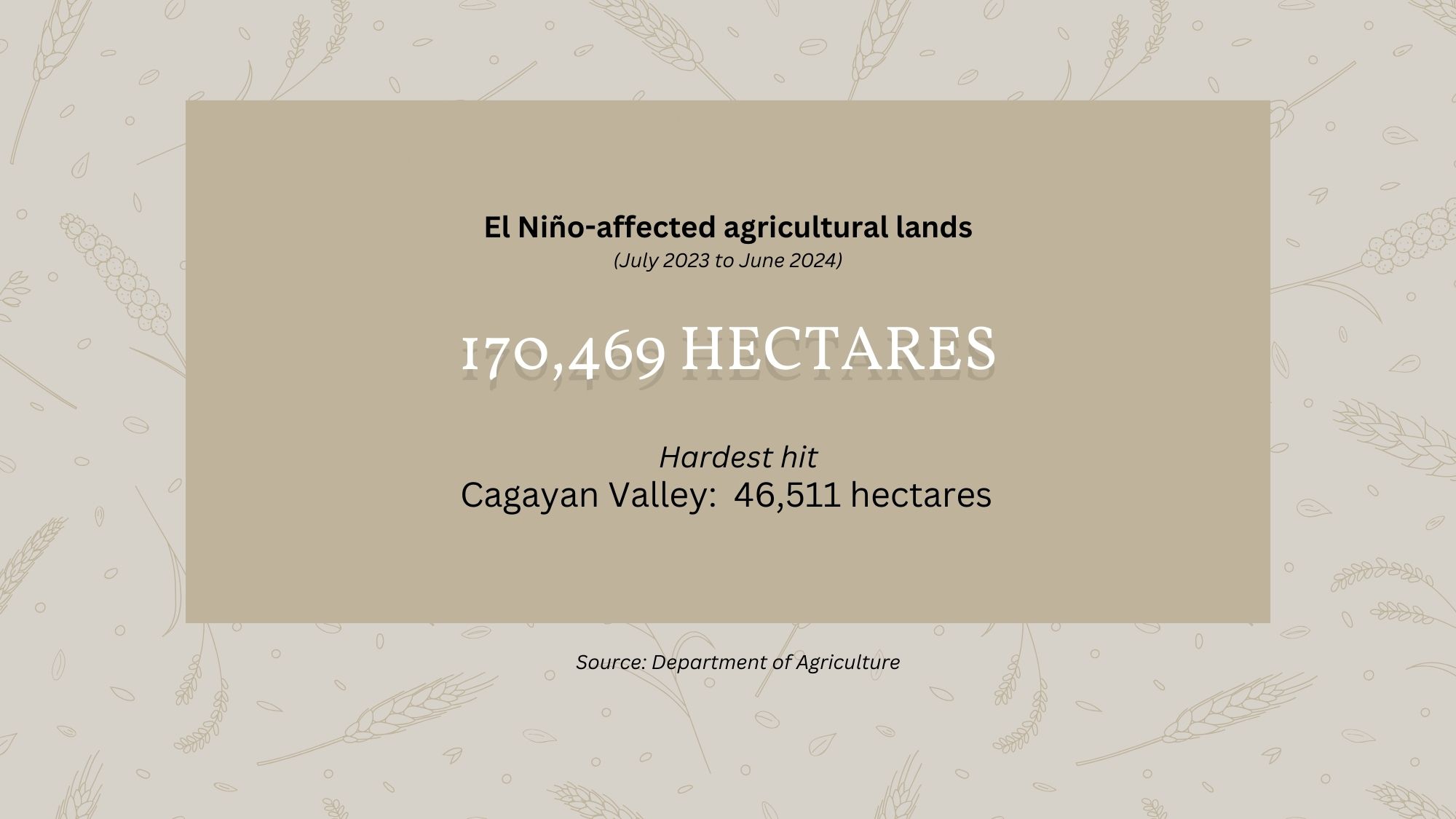

El Niño’s extreme dry weather scarred 170,469 hectares of agricultural land across the country, data from the Department of Agriculture showed. Cagayan Valley was the hardest-hit with 46,511 hectares of agricultural lands affected, followed by Western Visayas, and Mimaropa.

This year marks the fourth time that the Philippines experienced a strong and mature El Niño in less than 30 years, according to the government’s Task Force El Niño. The country also experienced the same phenomenon in 1997, 2009, and 2015.

Now, Filipino farmers can only look up to the heavens and hope that they can withstand what is poised to be another blow from nature’s fury.

After five decades of changing seasons, 67-year-old Quentin Aveno continues to till the soil in Barangay Alitas, Infanta, Quezon. In this photo, Quentin operates a power tiller to cultivate land ahead of the onset of the La Niña phenomenon.

Alitas Farm Association

Quentin Aveno, 67, has been growing rice in Barangay Alitas in Infanta, Quezon for more than five decades. He and his family survived the last recorded La Niña episode from 2021 to 2023 when Typhoon Odette struck, then managed a paltry harvest under arid conditions during the last El Niño.

The harvesters of Barangay Alitas in Infanta were among the 180,000 farmers and fisherfolk who endured the hot temperatures from July 2023 to June 2024, and are now preparing for heavy rains to be enhanced by the looming La Niña phenomenon.

As yet another bout with extreme weather beckons, Quentin and his fellow farmers in Alitas are bracing for the worst.

“Sa salita ng paghahanda ay hindi po kami masyadong prepared dahil ang nangyari po noon ay dito po sa amin ay seasonal ‘yung pagtatanim. Two times po ang cropping namin a year. Kaya ang nangyari po noon ay kami po ay nagtanim noon ay nakadepende po kami sa daloy ng tubig ng irrigation,” Quentin said, noting that the drought caused problems in their water irrigation.

(We were not prepared because our planting is seasonal. Cropping is done twice a year. During the El Niño, we were unable to plant our crops because we depend on irrigation.)

Aveno said he and his two children usually reap more than 300 sacks of rice, or 85% to 100% per hectare during normal weather conditions. The El Niño, marked by the unusually warmer than average sea surface temperatures and sparse rainfall, led to low harvests.

“Kami po ay lahat bagsak ang ani. Iyong inaani ko po noon na 370 something na kaban, ay naging 157 na lamang,” said Aveno.

(All of us harvest less than usual. I usually harvest around 370 sacks of rice but now I only harvested 157 sacks.)

Being at the remotest area of Infanta town, Aveno said there was not enough water coming from the irrigation system—which runs through 36 barangays along Agos River—to their area near the Quezon coast when they were hit by the recent El Niño.

“Nagkakaroon po ng supply ng tubig kaya lang hindi po supisiyente. Dahil ang lugar po namin ay kaduluhang bahagi po ng bayan ng Infanta, dito po kami sa Barangay Alitas, kung saan po kami ang pinakadulong barangay,” he said.

(There is a supply of water, but it is insufficient because our area, Barangay Alitas, is at the farthest part of Infanta town.)

“Bago po makarating sa amin ‘yung tubig ay sa ibang barangay muna po dumadaan ang tubig, kaya nahaharangan po ‘yung mga tubig bago kami magkatubig,” he added.

(Before the water reaches our rice fields, it passes through other barangays. This affects the flow of water before we get any supply.)

Overall, the agricultural sector incurred P9.89 billion worth of damage and losses to agriculture due to El Niño, state agriculturists said.

Under the Presidential Assistance to Farmers, Fisherfolk, and Families (PAFF) program which started in May 2024, the Office of the President allotted P10 million to P50 million per province for identified beneficiaries, such as farmers, fisherfolk, and their families, who were affected by the El Niño phenomenon.

“Depende sa severity ng impact ng El Niño sa LGU ‘yung pagbibigay. So mas malaki ‘yung nakuha ng mas maraming damage to agriculture and aquafisheries. Ten million pesos minimum and 50 million pesos ang max per province ang binigay,” said Joey Villarama, spokesperson for the Marcos administration’s Task Force El Niño.

(Disbursement depends on the severity of El Niño’s impact on the LGU. Those which suffered more damage to agriculture and aquafisheries received more. A minimum of P10 million and up to P50 million per province was provided.)

Data from Task Force El Niño showed that a total of P82,610,000 was distributed to four CALABARZON provinces, namely Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Quezon, and Rizal, of which P28,810,000 was allotted for farmers in Quezon.

“Not all La Niñas are created equal [because] there's another effect depending on the intensity of the La Niña. If it's a weaker La Niña, sometimes other teleconnections or other patterns can become the dominant one.” –AccuWeather lead international forecaster Jason Nicholls

However, Lorna Calda, officer-in-charge - director of DA’s Field Operations Service, acknowledged that some farmers were unable to receive aid. Not because they were ineligible, she said, but because the budget was simply inadequate for everybody who needed help.

According to Calda, the target amount for each PAFF beneficiary is P10,000. The amount was determined after stakeholders reached what she called an “agreement.”

“So kapag P10,000, ang maximum na mabibigyan lang is nasa 5,000 farmers lang. Kaya lang may mga areas na ang naapektuhan ay more than 5,000 farmers,” Calda said.

(With the target of providing P10,000 each, only up to 5,000 farmers can be given assistance. But there were affected areas with more than 5,000 farmers.)

“Kaya doon sa naging agreement is not more than P10,000 ‘yung ibibigay sa mga farmers. So depending on the number of farmers affected ang ibinibigay na allocation ng Office of the President,” she added.

(The agreement is that the farmers would receive not more than P10,000 each. So the allocation from the Office of the President depends on the number of affected farmers per area.)

As far as the Alitas farmers are concerned, however, there was no agreement reached on the distribution of PAFF funds.

What they did receive was PAFF cash aid for a livestock farmer who lost eight piglets during the El Niño, and crop insurance for five farmers from the Philippine Crop Insurance Corporation, an officer of the Alitas farmers’ group told GMA News Online.

Moreover, Aveno said he and his fellow Alitas farmers have yet to receive any assistance from the municipal agricultural office (MAO) to cushion the impact of El Niño, noting that they have only been provided with training on climate change adaptation, among others.

GMA News Online has repeatedly reached out to Infanta’s MAO since July, but it has yet to respond as of this posting.

Barangay Alitas lies in a remote area of Infanta, Quezon. During El Niño, water from the local irrigation system becomes sparse as it passes through 36 barangays along Agos River before reaching Alitas near the Quezon coast.

Alitas Farm Association

Task Force El Niño said all farmers affected by El Niño and La Niña should receive tangible forms of assistance from the DA, Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE), and Office of Civil Defense (OCD).

“Hindi lang dapat training, kundi mayroon talagang tangible assistance (They should not only receive training, but also tangible assistance) whether in the form of cash, in the form of seeds, in the form of farm inputs or implements,” said Villarama.

While the DA has an allocation of P1 billion for the quick response fund (QRF) in its annual budget, this is limited to production inputs, repair and rehabilitation of small-scale irrigation facilities and production facilities, and compensation for culled animals.

Worse, Calda said the QRF has been fully utilized to address previous calamities, such as the African Swine Fever and the shear line that affected Caraga and Davao regions. “Ang concern lang namin ngayon is sana-replenish. Nag-request na rin kami sa DBM ng replenishment at sa NDRRMC,” Calda said.

(Our concern now is for the fund to be replenished. We already requested this from the Department of Budget and Management and the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council.)

According to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (NDRRM) Plan 2020-2030, the country’s long-term roadmap towards disaster resiliency, the government cites the urgent need for the bureaucracy to have a “deeper understanding of a community’s vulnerability and adaptive capacity.”

“The conduct of risk assessments at the national and sub-national levels has significantly improved since RA 10121 was passed into law,” the document read, referring to Republic Act 10121 or the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010.

“While there is also an observed increase in implementing an integrated risk assessment approach, LGUs have focused more on identifying hazard and exposure and less on analyzing the socio-economic factors that increase vulnerability and overall risk,” it added

While the RA 10121 provides that not less than 5% of the estimated revenue from regular resources of local government units (LGUs) shall be set aside for disaster risk reduction management activities, issues were raised in budget allocations.

Citing a report by state auditors in 2014, the NDRRM Plan noted that there were higher budget allocations in cities with higher revenues compared to lower income localities.

Further, the plan flagged that fund utilization “tends to focus on reactive or ex-post DRRM activities such as preparedness to respond, relief to rehabilitation activities than prevention, mitigation and preparedness.”

“LGUs need to be guided on how to maximize their local resources first, namely, the LDRRM Fund and Local Development Fund and access funding from the national government to effectively invest in DRRM activities,” the plan said.

Under the Marcos administration's Presidential Assistance to Farmers, Fisherfolk, and Families (PAFF) program, P28.8 million is allotted for farmers in Quezon who were affected by the El Niño phenomenon.

Alitas Farm Association

Further, the plan called for utilization of social media to disseminate critical information especially during times of distress.

“The use of social media and technology must also be maximized and utilized properly. A clearer protocol on information dissemination, warning system through social media, and response lines must be established,” the plan read.

“The form, content, and dissemination of the data must be accessible to all, especially the vulnerable groups. The availability of accurate, comprehensive, and updated data at the local level will lead to timely and informed decision-making,” it added.

The NDRRM plan also provides that historical data should be reviewed to assess how disaster events were handled.

“By learning from previous disasters, loss and damage may be significantly reduced. It is apparent that any effective disaster mitigation program should be built within the context of the community; community awareness on disaster management is imperative,” it read.

While there are things that can be improved, the Task Force El Niño is satisfied with the government's efforts in mitigating the drought.

“So there are things that definitely can be improved on, pero as I mentioned overall, if we are basing it on the hectares that were damaged, this year compared to the worst El Niño year, which was 1997, maganda ang response ng gobyerno (the government had a better response this time),” said Villarama.

Government data showed that 677,441 hectares of agricultural lands were heavily affected by the El Niño in 1997. In comparison, figures in 2024 showed that only 170,469 hectares were hit by El Niño.

Further, the task force said it has also been trying to resolve issues with obtaining data, especially from far-flung areas that have also experienced El Niño’s impact.

“So for a time there was a lag in the delivery or in the reporting of actual figures dahil ‘yung ibang areas ay inaccessible, far-flung. So as a consequence of that, hindi naibibigay ‘yung necessary tulong,” said Villarama.

(So for a time, there was a lag in the delivery or in the reporting of the actual figures because some areas are inaccessible or far flung. So as a consequence of that, the necessary aid was not being provided.)

Amid the El Niño phenomenon in December 2023, Calda said, the NIA distributed 141 wheeled excavators to field offices to maintain the irrigation facilities.

Based on the DA El Niño Mitigation and Adaptation Plan, the actions that the agency prepared for El Niño include desilting irrigation canals and pre-positioning of pumps and engines for water management; positioning of agricultural inputs; developing cropping calendars and adjusting the planting schedule for crops.

In areas without local agriculturists, the task force said the DSWD provides data on the affected farmers who will be given assistance.

However, the government has already been exerting efforts to encourage more people to get into the farming sector, the task force added.

“Sana nga ma-start natin ‘yung culture, ‘yung interest sa farming para madagdagan din ‘yung ating farm technicians, agricultural engineers kasi sila talaga ‘yung nakakatulong in getting the data we need para malaman natin kung ano ‘yung tulong na maibibigay sa mga magsasaka,” said Villarama.

(I hope we can start a culture which can put an interest in farming so we can have more farm technicians, agricultural engineers. These people can help us get data to identify the needs of our farmers.)

“There’s always something to learn. Considering yung flooding natin, this recent disaster (Carina) calls on us in the government, especially the concerned agencies, to assess and improve our flood control management. ‘Yung system na ‘yan na palaging ine-espouse natin na magkaroon ng masterplan, to revisit din yung existing policies natin.” –Office of Civil Defense spokesperson Edgar Posadas

Even before PAGASA announced the end of El Niño on June 7, farmers across the country have been bracing for the La Niña phenomenon, which is expected to commence towards the end of 2024.

For the farmers of Barangay Alitas, however, La Niña—despite its devastating effects—is somehow more bearable than El Niño. “Nitong nakaraan talagang totally tuyo po siya. Maputi po talaga ‘yung lupa, malalaki po ang bitak ng lupa,” said Aveno. (During the last El Niño, the ground was totally dry. The ground was totally white, and bore big cracks.)

“Samantalang kapag [tag-ulan], ang palay naman po natin ay high-resistant sa mga tubig. Depende po sa variety. Pero kapag po ‘yung tag-tuyot, kahit anong klaseng variety po 'yan, wala po diyang high-resistant,” he added. (During the rainy season, the rice is highly resistant to water. But no rice is highly resistant during the dry season, no matter what the variety is.)

A farmer stands in the middle of his battered rice field in Barangay Alitas in Infanta, Quezon after Severe Tropical Storm Enteng hit the country in September 2024.

Alitas Farm Association

According to state weather forecasters, a “weak” episode of La Niña is expected over the country for the first time since 2006 or nearly 20 years.

In an interview with GMA News Online, US-based weather forecast service AccuWeather said the Philippines would experience fewer tropical cyclones during the upcoming La Niña.

“Rainfall should be above normal with temperatures near normal. The number of tropical cyclones impacting the Philippines will be below average with a significant reduction in the number of strong tropical cyclones,” Jason Nicholls, AccuWeather lead international forecaster, told GMA News Online in an interview.

Nicholls noted that the impact of La Niña is not always the same due to other climate patterns, like irregular change in sea surface temperature in the Indian Ocean.

“The big thing we can take away is not all La Niñas are created equal, but we kind of knew that there's another effect depending on the intensity of the La Niña. If it's a weaker La Niña, sometimes other teleconnections or other patterns can become the dominant one,” Nicholls said.

He added, “I would think overall just looking at the trends of global temperatures, I probably would see more extreme heat events and more drying across the Philippines as we go forward during an El Niño-type event.”

The government knows that continuous preparations should be made to mitigate its impact on the agricultural sector. Recent storms that hit the Philippines–even without the La Niña–have already devastated numerous farmlands, fishponds, infrastructure, and communities across the countries.

In May, Marcos assured the public that the government was prepared to address the possible effects of La Niña.

''Ongoing naman iyan eh. There’s no need to do anything special. We are already doing everything that we can do to prepare for, well, another El Niño and the La Niña that we are anticipating will come,'' Marcos said in an ambush interview in Tacloban City.

Just two months later during his third State of the Nation Address, Marcos said the government has provided crop insurance to all El Niño-affected farmers.

“Matindi ang naging epekto ng dumaang El Niño, lalo na sa mga sakahan. Sa tinamong pinsala mula sa pagkasira ng mga pananim, nagkaroon ng proteksyon ang ating mga magsasaka sa pamamagitan ng ating binigay na crop insurance (The impact of the recent El Niño was severe especially on farms. Given the damage to crops, our farmers were protected through the crop insurance we provided),” said Marcos, adding that more than P6 billion worth of compensation was given to affected farmers and fisherfolk.

Further, the Chief Executive highlighted then that over 5,500 flood projects were already completed, and that other similar projects were being constructed in preparation for La Niña.

“Isa na rito ay ang Flood Risk Management Project sa Cagayan de Oro River, na magbibigay ng pangmatagalang proteksyon sa mahigit anim na raang ektarya ng lupa at animnapung libo nating mga kababayan,” said Marcos. “Isa pa ay ang proyekto sa Pampanga Bay na magsisilbing karagdagang lunas sa mga pagbabaha.”

(Among our projects is the Flood Risk Management Project in Cagayan de Oro River that will provide long-term protection to more than six hectares of land and to 60,000 people. Another project is in Pampanga Bay that will also mitigate floods.)

Farmers in Barangay Alitas in Infanta, Quezon operate a rice transplanter to place rice seedlings on a field.

Alitas Farm Association

Task Force El Niño said the government is pushing for more drainage water management systems, which includes dams and water irrigations, that would help manage the effects of both the El Niño and La Niña phenomena.

“So ang instruction ng President, not just for the coming La Niña, pero kasi nga regularly we have the typhoon season and the regular rainy season, [is to establish] more water impounding systems or catchment systems,” said Villarama.

(The instruction of the President, not just for the coming La Niña, is to establish more water impounding systems or catchment systems since we regularly have typhoons.)

Also part of the government’s water management strategy to handle extreme weather is to set up more dams.

“‘Yung National Irrigation Administration (NIA) has reported that between now and 2028, marami namang maitatayo at magiging operational na dams. Dams do not only serve to impound water, gusto rin ng Pangulo na multi-purpose siya. So for power generation, for aquaculture, pwede rin siyang for tourism, at saka flood control,” Villarama added.

(NIA reported that between now and 2028, a lot of dams will be built and become operational. Dams do not only serve to impound water. The president wants it to be multi-purpose. So for power generation and aquaculture. It can also be for tourism and flood control.)

Meanwhile, state weather bureau PAGASA said a strong La Niña is seen to hit the country in the next three to five years while heavy rains will continue to be more extreme.

PAGASA weather specialist John Manalo said one of the challenges in responding to these weather changes is putting into layman’s terms the information for the public to easily understand.

“Siguro kung paano natin mababanggit sa mga tao. Instead na sabihin natin na dahil sa La Niña ‘yan, puwede natin banggitin na ano ‘yung magiging impact sa kanila. I think mas magiging madali sa kanila na mag-prepare,” Manalo said.

(It is how we deliver the information to the people. Instead of saying that the weather conditions are because of La Niña, we can instead discuss the impacts. I think they can easily prepare with that information.)

The NDRRM plan provides that PAGASA and local government units should effectively communicate to the public.

“Hindi lang dapat training, kundi mayroon talagang tangible assistance, whether in the form of cash, in the form of seeds, in the form of farm inputs or implements.” – Joey Villarama, Task Force El Niño spokesperson

Aside from prepared responses, the government should also revisit existing policies concerning disaster preparedness and come up with a masterplan for flood mitigation at a national level, Office of Civil Defense spokesperson Edgar Posadas said in an interview.

“There’s always something to learn. Considering yung flooding natin, this recent disaster (Carina) calls on us in the government, especially the concerned agencies, to assess and improve our flood control management. ‘Yung system na ‘yan na palaging ine-espouse natin na magkaroon ng masterplan, to revisit din ‘yung existing policies natin. We continue to capacitate our local government units. It is always a shared responsibility para mas magawan nag paraan ito,” Posadas said.

(There’s always something to learn. Considering our problem with flooding, this recent disaster calls on us in the government, especially the concerned agencies, to assess and improve our flood control management. We always espouse having a master plan and revisiting our existing policies. We continue to capacitate our local government units. It is always a shared responsibility to work our way through this.)

While “pockets of meeting” have been conducted regarding the masterplan for the flood mitigation master, Posadas expressed hope that the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA), the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), and the Metro Manila Council could sit down and have more in-depth discussions on the matter.

With farming as their way of life, the tillers of Barangay Alitas in Infanta, Quezon must rise anew to the challenge of adapting to extreme weather changes posed by the El Niño and La Niña phenomena.

Alitas Farm Association

The NDRRMC plan states that a bottom-down approach is more effective in implementing disaster preparedness, prevention, response and recovery, where the communities are involved in disaster response and recovery plans.

Calda urged Filipino farmers to be active and form an association so they could easily report their concerns to their municipal agriculturists.

“I-submit nila ‘yan (they will submit their report) through the municipal agriculturist office. Then, the municipal office will submit it to the (agricultural) provincial office, then the provincial office will submit it to the regional office,” Calda said.

She added that there should be localized weather forecasting for more accurate weather forecasting in certain areas.

With a life dedicated to tilling the soil, Aveno has been able to make a meaningful harvest by having his two children finish college degrees in Commerce and Information Technology.

The lives of Barangay Alitas farmers do not only revolve around planting. For generations, they have learned to adapt. Some of them are also into fishing, woodworks, even alcohol distillery, and other forms of livelihood to make ends meet and survive even the harshest of seasons.

“Doon sa ecosystem po namin, kapag kami po ay nakapagtanim na po kami, nakapag-weeding na kami, ‘yung amin pong ibang mga members, mayroon pong mga carpenter, mayroong nasa dagat, nanghuhuli ng isda, sa mangrove areas, nanghuhuli po sila ng shrimps, crabs, at seashell. at gumagawa rin po sila ng lambanog,” he said.

(In our ecosystem, once we are done planting and removing weeds, some cooperative members work as carpenters, catch fish, shrimps, crabs, and seashells at our mangroves or in the open sea. Others make distilled palm liquor or lambanog.)

Nature’s bounty gives life to the Alitas farmers, but it is nature’s fury of heat and rain that threaten to bring them to their knees anew. — VDV/RSJ, GMA Integrated News