We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

Part 2

A part-time teacher and full-time mother. A writer. A community organizer.

These are the stories of wives who shared their husbands with the country and dreams of a better life not only for their families but for the people. They also share the common fate of losing their spouses to the cause, either going missing or detained, or getting killed and being declared as martyrs.

Beyond the immeasurable pain of dealing with the loss and the ambiguity of the future of their loved ones, they soldiered on – raised the family, carved their own niche, looked after one another, carried on with the advocacy.

The words of Cuban leader Che Guevarra could not have been more apt, “A true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love.”

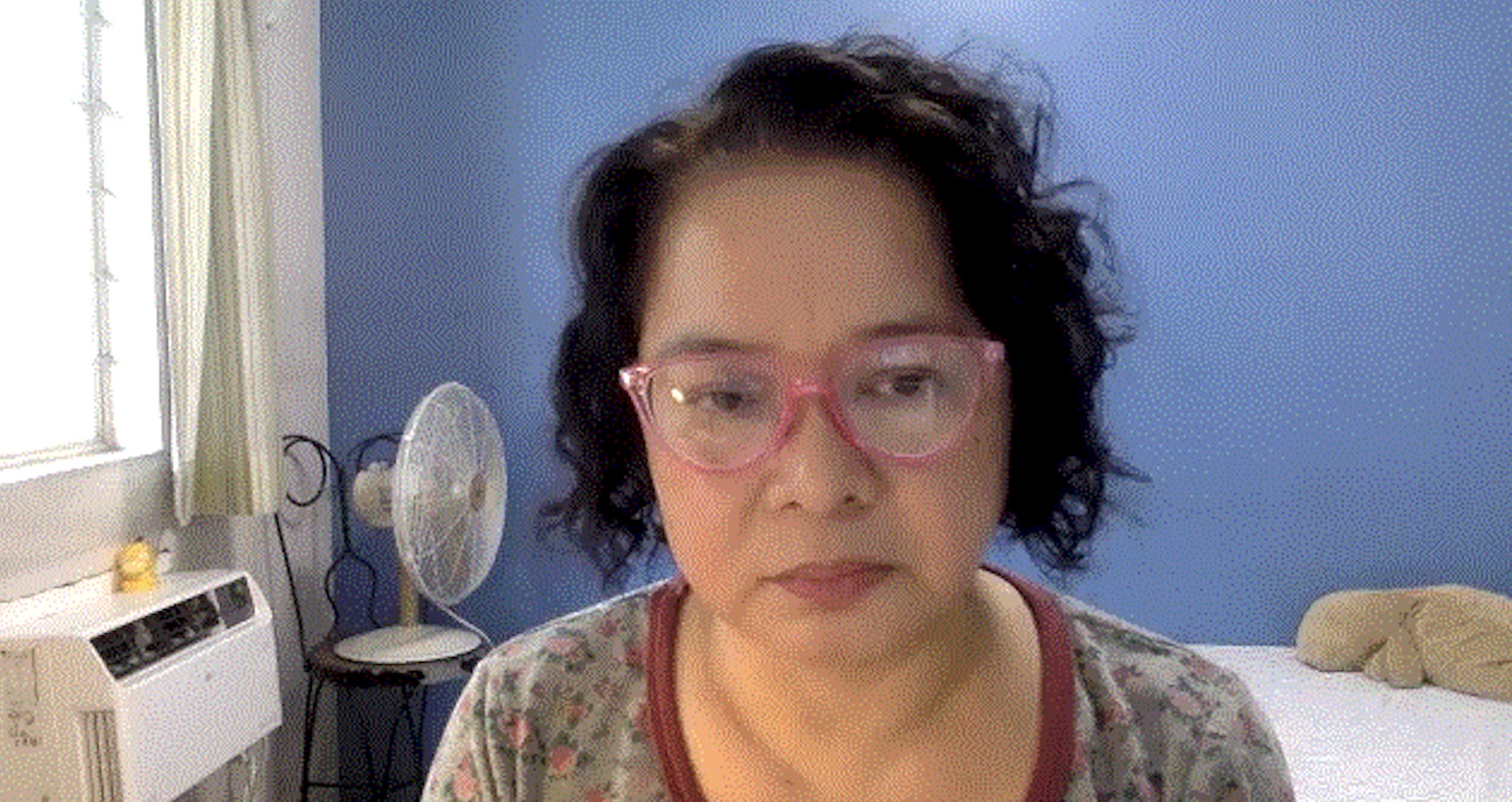

(R) Evelyn Mangulabnan, mother of Earnest Zabala

“Bakit tayo simba nang simba hindi naman tayo pinapakinggan ng Diyos? Dasal ako nang dasal na makalaya na si Tats, hindi naman siya pinapalaya. Siguro walang tenga ‘yung Diyos kasi hindi niya tayo naririnig.”

(Why do we go to church when our prayers are not heard? I always pray for Tats’ freedom, yet he remains incarcerated. Maybe God doesn’t hear us.)

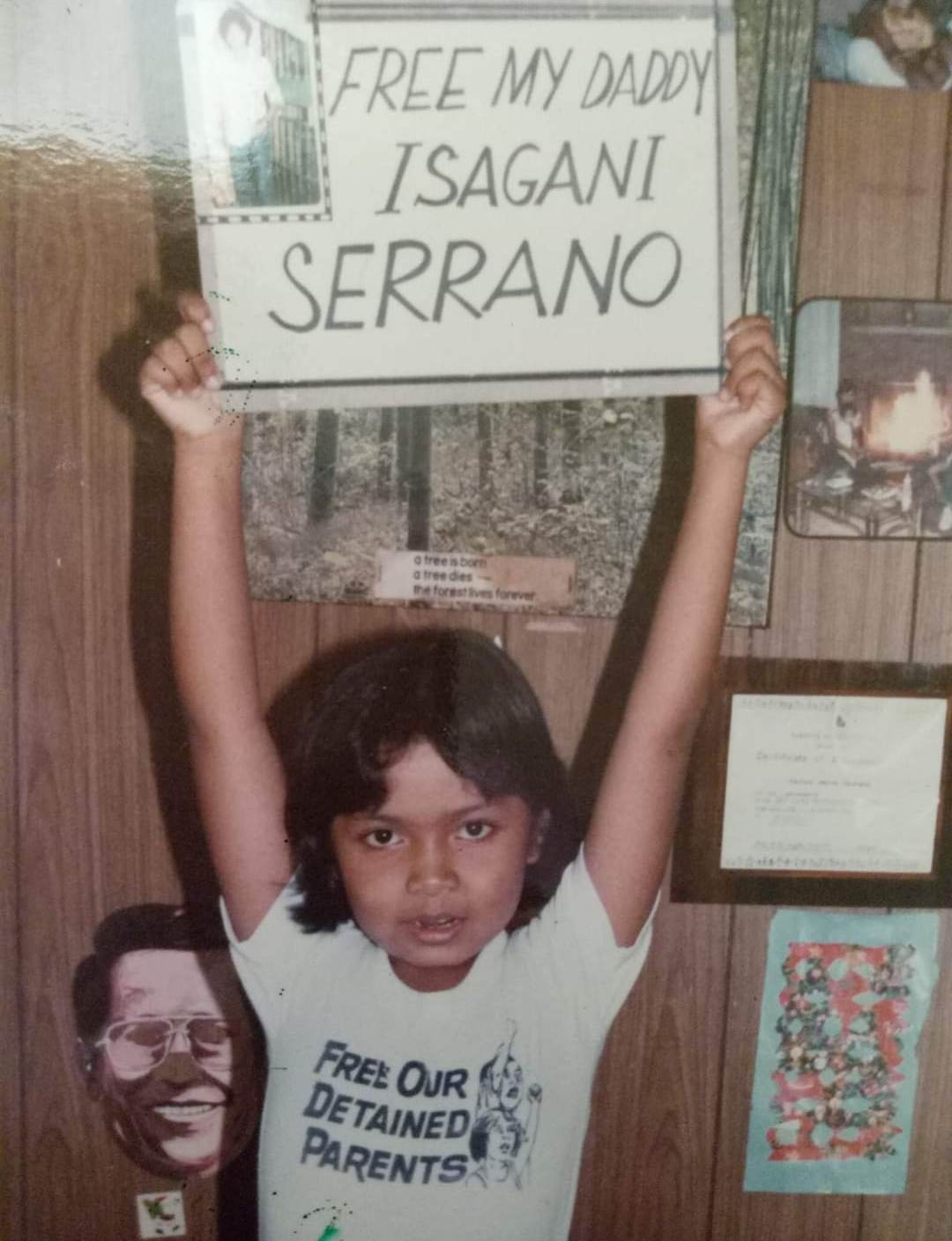

Evelyn “Len” Serrano felt her heart shatter when she heard these words from her son, Karl, when her late husband, Isagani “Gani” Serrano was detained. They had just attended mass before their usual visit to his detention center in Camp Crame, Quezon City, and had requested her child to pray for the release of his “Tats,” as he called his father.

Gani, a known advocate for sustainable development, peace, and civil rights, was among the hundreds of political prisoners under Martial Law era. He was first arrested in 1973 while organizing communities in Tondo, Manila.

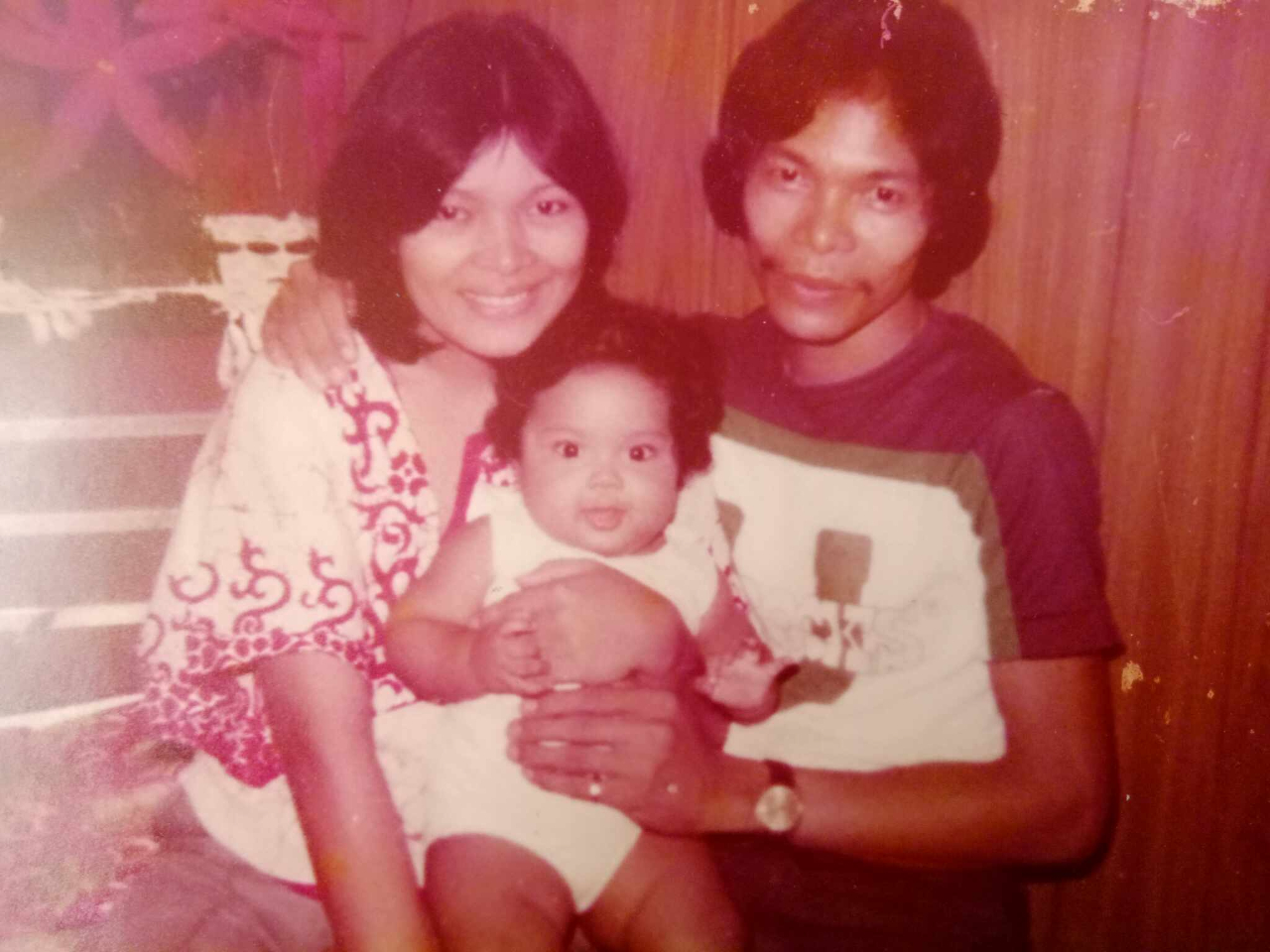

Len, a social worker helping poor families fight forced displacement for the supposed rehabilitation of the slum area, met Gani after his release in 1975. They got married in 1976. Six years later, Gani was again arrested with three other community organizers in 1982 during a crackdown on the growing burgeoning mass movement.

“Their arrest was on the news but the military denied apprehending them. They were considered victims of enforced disappearance for two to three weeks because the authorities didn’t want to acknowledge it,” Len said.

“By accident, we received information they may be detained at a secret place where four people were reportedly seen being placed in individual sacks,” she added.

A vigil lasted for days in front of the clandestine facility. Their legal counsel filed a writ of habeas corpus before the Supreme Court (SC) for their surfacing and when presented, Gani was skin and bones. His skin turned yellowish and his body full of cigarette burns. The victims said they were tortured inside the facility and were chained to their beds while continuously interrogated for days and nights.

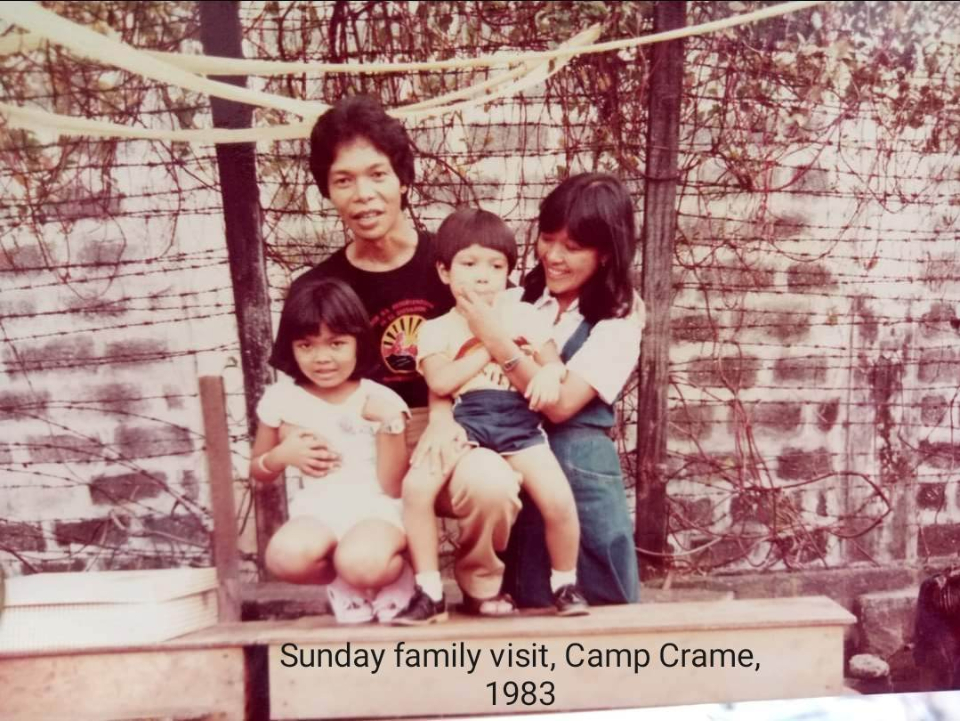

The SC ordered their transfer to Camp Crame in Quezon City, where they were imprisoned for nearly four years.

“The SC ruled for their transfer to a regular detention center. They were brought to Camp Crame but the visiting hall and detention center there was separated by layers of wires. We cannot even hear them or see their faces whenever we visit,” she said.

Love in a time of political turmoil is never easy. The same was true for Len and Gani who had to flee for their safety even before his imprisonment. With community organizers being targeted then, the couple lived in different places, moved from one house to another and assumed different identities to avoid raids and other forms of harassment — all while tending to their two children.

At one point, she said they only had one bag each, so they would be ready to flee anytime they would sense danger. They stayed in some houses for a month, longer in more secure shelters, before moving to a new place, and starting anew. It was grueling, but for Len, any place with them is a home.

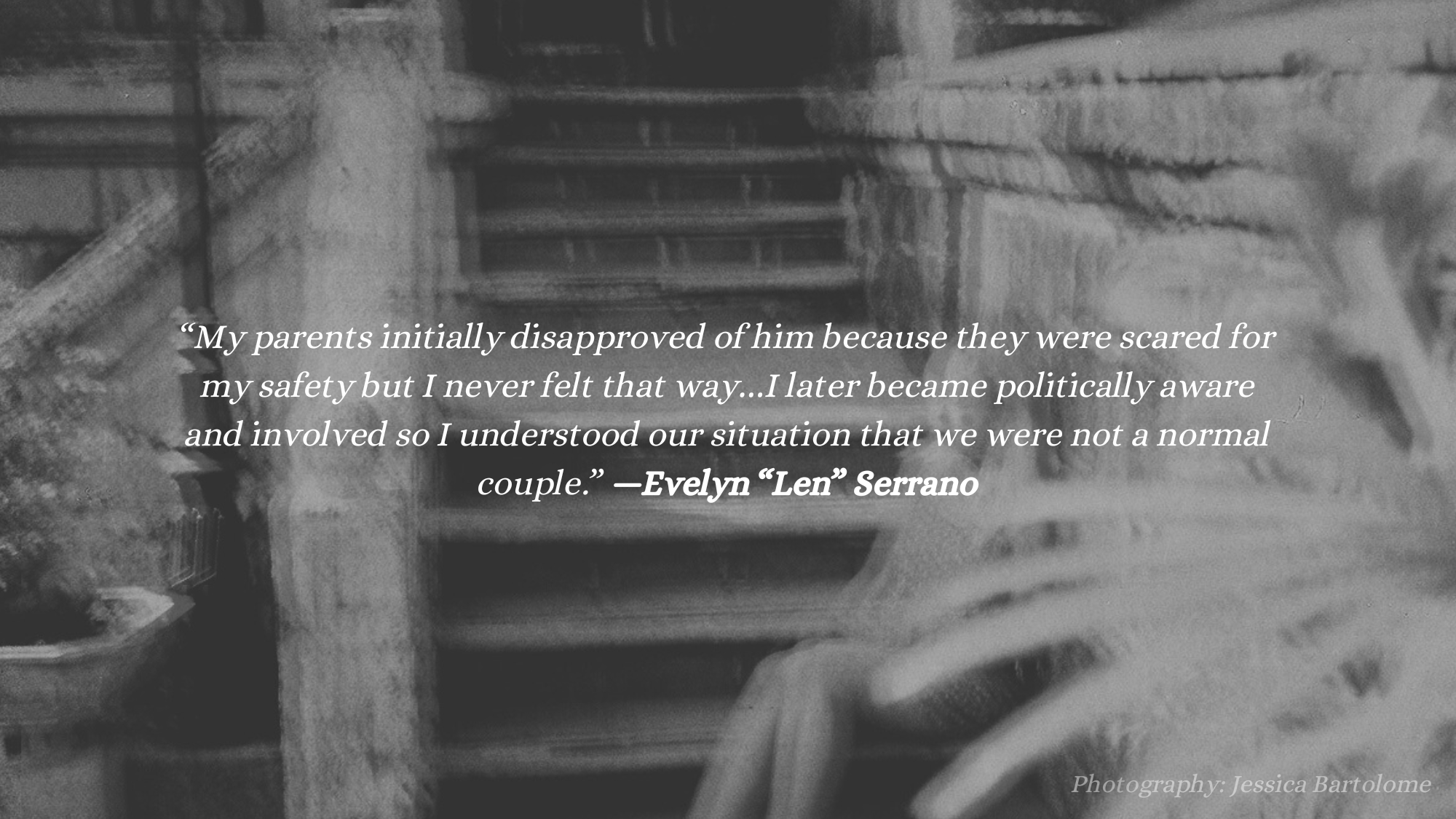

“My parents initially disapproved of him because they were scared for my safety but I never felt that way…I later became politically aware and involved so I understood our situation that we were not a normal couple. I also understood that his priority is to fight for the rights and organize farmers and sugar workers,” Len said.

“It was difficult, but we make up by decorating each house we occupied. We used mats as chairs and brought plants just to have a semblance of a living room,” she added.

Amid Gani’s detention, Len had to assume multiple roles. She was a wife, a mother, a community leader, and a breadwinner. Her new routine consisted of waking up early to prepare the food she would bring to Gani and other detainees before going to her office in Diliman, Quezon City. She would then meet and coordinate with the families of other political prisoners after working hours.

Inside the jail, the detainees suffered from lack of basic human rights while being separated from their kin. Len and the other families helped them by publicizing and lobbying for improved prison conditions, which the political prisoners fought for through a series of hunger strikes.

The jail management later allowed multiple visitors, and food to be brought inside, but not without security measures including strict body searches which Len described as degrading.

“The policies before were all subject to negotiation. Only one guest was allowed to visit prisoners before so we used to pay the guards to let us inside. Somehow, it felt like we were prostitutes paying them just so we could visit our relatives. It was degrading, especially with the body search, because some guards were groping us,” she said.

The Serrano family had to make the most of their borrowed time during their visits. After lobbying for its approval, the detention facility became an open house on Sundays and the families of the detainees were allowed to get together on weekends. They celebrated milestones and grieved tragedies together including their children’s birthdays, and the death of Gani’s close friend, fellow activist Edgar Jopson.

“If you’ll ask my children, they would say that one of the high moments for them is celebrating their birthdays and other kids’ birthdays in Camp Crame. We bring their cakes there and celebrate. We did that for four years,” Len said.

After the end of the Marcos regime, then-President Corazon Aquino ordered the release of hundreds of political prisoners in the country. After his release, Gani returned to developmental work and pushed for the implementation of a genuine agrarian reform. He also joined the Philippine Rural Reconstruction Movement and helped establish organizations such as the Social Watch Philippines and the Global Call to Action Against Poverty.

Len, meanwhile, continued to teach and with her involvement in human rights advocacy. She worked for the Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development, Task Force Detainees of the Philippines, Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates, and Amnesty International.

Their advocacies have progressed but not their marriage, which eventually ended.

“I had to decide to separate from him…That was the hardest decision I had to make because I thought our marriage would be for life but you really have to decide for your own sanity. We separated for so many reasons. But for me, it was difficult to watch someone you idolize slowly dying inside. It was so hard I felt like I was dying with him,” Len said.

“Our children cried after we told them we were separating but later they saw that it was indeed a better arrangement. Nevertheless, we remained a family,” she added.

In 2019, Gani passed away after battling lung cancer. At his wake, thousands came to pay tribute to his memory including farmer leaders, urban poor leaders, local officials, fellow development workers, members of the human rights community, social entrepreneurs, lawyers, bankers, journalists, technocrats, childhood friends, schoolmates, artists, and youth leaders.

“I never understood why he was always away when we were growing up. Sometimes I resented the fact that my playmates had their fathers with them at home and in school and we did not. After hearing your stories, now I understand. And I feel proud that he is my father,” his son said.

Their daughter, Toni, grew up to also become a human rights advocate. She worked at the Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances and had fought alongside the families of victims of enforced disappearances in the country including the Burgoses.

After Gani’s death, Len helped process the requirements for her husband’s inclusion in the honorees of the Bantayog ng Mga Bayani, a list of martyrs and heroes who fought Martial Law and the authoritarian regime. She contacted Gani’s friends and asked for testaments and endorsements for his inclusion.

He was honored at the Bantayog in 2023.

“We helped produce the documents and requirements for his inclusion to the Bantayog ng Mga Bayani list because their process is very thorough. We collated information about his family background and circumstances, to write the history of his activism,” Len said.

Even with the hardships, Len said she never regretted marrying Gani.

“A close friend told me that our lives do not end with the imprisonment or the loss of a husband or a partner. It was just the start of a new chapter of our lives,” Len said.

“For the wives, and families of political prisoners, let us take pride and be proud of them. They struggled and sacrificed for other people, for our fellow Filipinos, and for our country. We need to recognize that. Even if they were not part of the Bantayog, they are heroes in their own rights,” she added.

Maria Theresa “Miks” Padilla found an extended family with the imprisonment of her late husband, Sabino “Abe” Padilla, in 1982.

Abe was part of the “Vizcaya 13,” a group of activists illegally apprehended in Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya based on a search warrant and suspicions of subversion. It would later be known that the presidential commitment order issued for the case was signed six days after the arrest.

The group’s case would also become the landmark “Garcia-Padilla v. Enrile Case” after his mother, Josefina Garcia-Padilla, sought legal aid to oppose their apprehension. The Supreme Court (SC) sided with the administration on the controversial case and declared the arrest legal.

Miks said the SC decision became one of the cases that enlightened the legal world about the harrowing misdeeds occurring under Martial Law.

“I was continuing my studies at UP when Abe travelled to Nueva Vizcaya for a field trip. He was supposed to be gone for only two to three days but on the second day, one of his friends approached me and like a movie cliché, said that he was arrested with 12 others,” she said.

Shock enveloped her body but with the dangers of activism under Martial Law, Miks said she was not surprised. She was then advised to refrain from visiting her husband in prison amid threats to her physical safety.

“I think I was calm when I heard the news. The only time I cried was when I was told not to visit him because I might be wrongfully involved in the case and might also be arrested,” she said.

Abe Padilla. Photo from Bantayog ng mga Bayani Foundation

For five months, Miks communicated with her husband through notes and letters being passed by friends and relatives visiting Abe. Words brought comfort but the mental distress over the situation was inevitable.

“I think there’s always anxiety. I think relatives and friends of detainees always go through this process…and that’s normal. At the end of the day, you just hope that he is alive and his companions are alive,” she said.

Abe remained in detention for three years. Miks would visit him on days without security concerns, bringing him food and books. Inside the prison, Abe finished reading classical books on Anthropology and continued making artwork, which she sold in Manila for additional income.

Amid the struggles, the couple worked hard to make life normal for their son, May-i. He was one of the three boys who would visit and stay at the detention center, growing close to all the political detainees who treated them like their own nephews.

“We try to make it as normal for him as possible. Whenever they were in the detention center, they would stay in a big room with three-decked bunk beds. He thought he just had a lot of uncles who were taking care of him…Some volunteers visit the detainees so when my son is there, they would take him out to play,” she said.

“He was still a baby when his father was arrested so he became used to travelling to Bayombong…I think he adjusted very well. It wasn’t a trauma as such because by the time he became conscious, the detainees were under much better living conditions,” she added.

Miks worked two to three jobs to support their family with Abe in detention. She was a student assistant, academic researcher, and part-time researcher and documenter for the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines.

Their family traditions also shifted, with May-i celebrating his birthdays in Bayombong, and then visiting Abe in the detention facility for Christmas and New Year’s Eve.

“We try to make every occasion special. What we’re celebrating is being together,” she said.

Looking back, Miks considers her family among the “lucky ones” with her husband and his companions having relatively better prison conditions and getting spared from torture. They also had a strong support system and were able to maintain their relationship with the families of other political detainees in Bayombong even after their release.

“I think they were among the lucky ones because they had that kind of space. I think it was not a normal atmosphere for detention centers. And since he came from Manila, some of his co-detainees were teachers and one was a doctor…It’s unfair but I think they were given a kinder treatment,” she said.

“The provincial commander was also trying to show there was a human face to the military under his command which was not perceived in general by the public,” she added.

The Padilla family slowly moved forward following Abe’s release in 1985. However, the scars of the incident persisted in small details such as Abe stopping to eat bangus (milkfish), the food often served in prison.

He also tends to flare up easily when questioned by authorities. He developed a renewed eagerness for travelling, with their family continuing to visit places including Mt. Maculot in Batangas where they first experienced mountain trekking together.

“I also told my children growing up that for whatever reason, if you would be late coming home or if there is a delay — even if it is for a reason I don’t like — tell me. I would rather know than not because that sense of not knowing whether someone is in danger or not, that’s the heaviest part,” Miks said. “I asked them to always inform me of their whereabouts. It’s not a matter of control but just to make me feel better.”

Abe continued his studies and earned a doctoral degree in Anthropology in 1991. He also became a professor in a state university and pursued various projects including the development of a geo-mapping system to better understand the health concerns of indigenous peoples (IPs).

Miks pursued developmental work, specifically on the plight of IPs. She is currently a development anthropologist working with IPs in the women’s health movement.

In 2013, Abe succumbed to cancer. Miks recalled the atmosphere during his wake was never gloomy but festive, making it feel like a “celebration of his life.”

Eleven years after he passed away, she said she always cherishes their good memories.

“You are just happy with what you had together. Of what you have in your life and what he had in his life. You don’t want that to be overridden by the fact that you were separated,” she said.

“And any death, especially of someone close to you, is saddening. But it’s also knowing that they never really left. Even when he was detained, we were physically apart but he had always been there as my partner. The same goes for death, the good things that have arisen from our relationship are still there. That cannot be taken away by any circumstances,” she added.

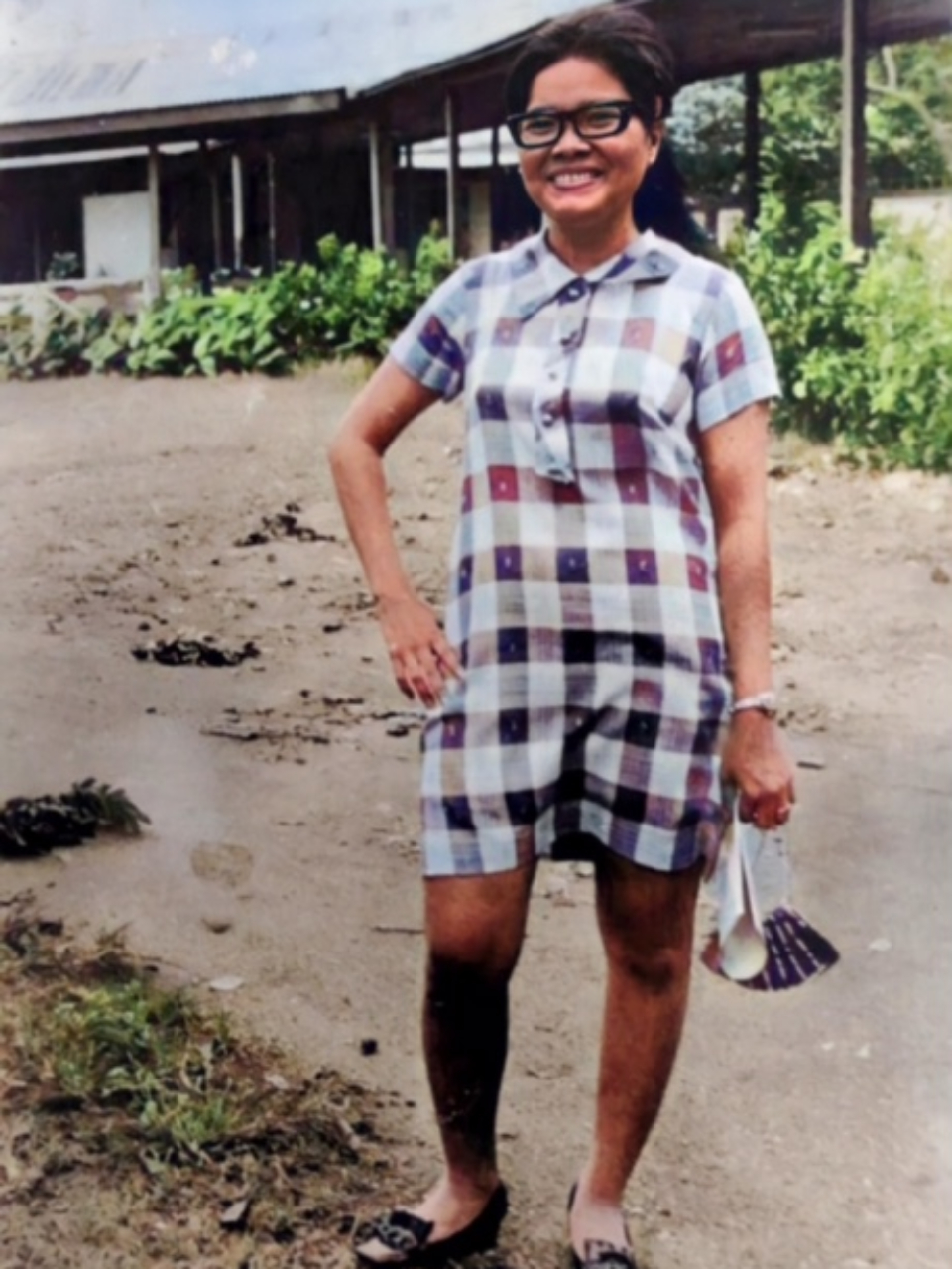

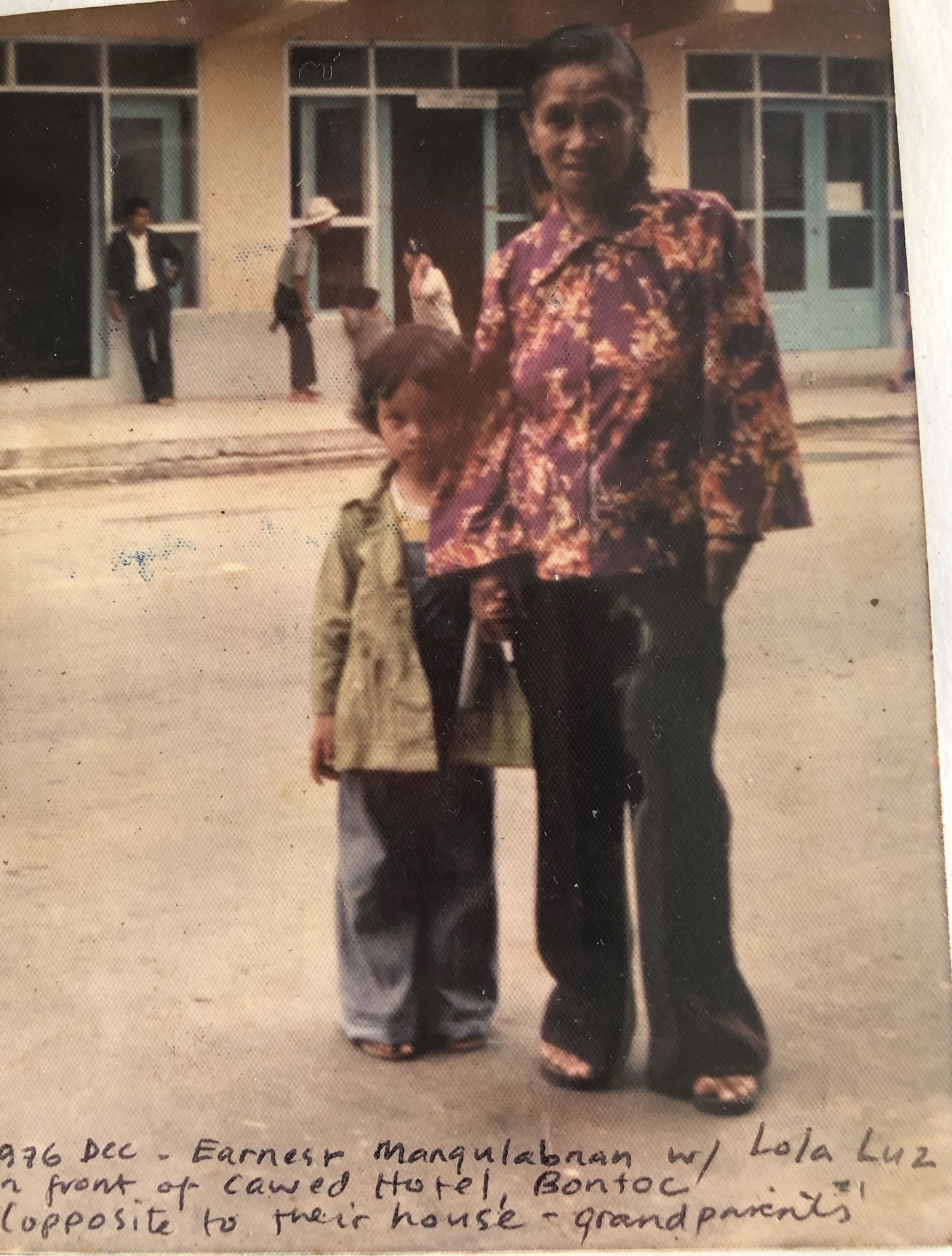

Earnest Zabala did not have personal memories of her parents.

Only a few months old, she was left to her relatives when her parents, known activists Evelyn and Ric, were forced to go underground shortly after the declaration of martial law in September 1972 to avoid arrest.

It was in September 1977, when she was five years old, that her family would receive news that the couple had been killed in Nueva Ecija.

Earnest was left in the care of her paternal grandfather and grandmother who worked as a barber and as a dressmaker respectively in Bontoc, Mountain Province. She described their situation as “poor,” saying that they wouldn’t have been able to eat if her grandparents didn’t work.

Earnest Zabala interviewed by GMA News Online.

Her aunt, meanwhile, made sure that she would finish her studies.

“I’m lucky that even if I didn’t grow up with my parents, I was cared for. My aunt made sure that I don’t feel so deprived and she was able to make me graduate college on time. As much as she could, she really provided for me in all the aspects of growing up,” she said.

Earnest, however, said there were times that she felt that something was missing.

“The fact that you didn’t have someone to call mother or father. The fact that you didn’t have someone to talk to. Of course, everyone’s also busy. They also have struggles. Sometimes, I’m just left to my own devices,” she said.

Now at 52, Earnest said she would sometimes get pangs of jealousy whenever her friends would talk about going home to their parents for birthday celebrations, something their family did not celebrate for her parents due to grief.

“It’s like my heart hurts. It’s like a realization that it’s not yet over. Until now,” she lamented. “There are just some things that maybe you can’t move on from. So when it arrives, you just get on with it. It’s just part of your life. There’s no closure.”

Earnest also recalled how she also used to lie to her friends about the circumstances of her parent’s deaths to stave off questions when she was young. It was only a few years later that she was able to tell the truth.

“It’s about fitting in. It’s hard to explain. It’s like I knew that if they asked me questions, I wouldn’t be able to answer a lot of them,” she said. “It’s like the path of least resistance.”

It took a long time for her to come to terms with the thought that she was somewhat competing with the country, according to Earnest.

“Growing up din medyo may ano din ako, the sense of self ko, kasi yung— hindi ako— hindi ko kayang magalit sa mga magulang ko for leaving me behind. And unang tanong eh, bakit ba wala sila? And then ang next na tanong, kasi pinaglalaban nila yung bayan,” said Earnest. “And then yung next na realization ko doon would be: how can I compete with that? Mas importante naman yung bayan sa akin.”

(Growing up, I had a thing with my sense of self because I couldn’t get angry with my parents for leaving me behind. The first question I would be asked is why are they not here? And the [answer] would be, because they’re fighting for the country. And my next realization would be: how can I compete with that? The nation is more important than me.)

Earnest said this was part of the reason she started going to therapy.

Seeing them not as parents but as heroes of the country was a big obstacle for her to overcome, so much so that the decision to call them “nanay” or “tatay” only came to her three years ago.

“For the longest time, I didn’t know if it should be mommy, mama, papa, nay, tay,” she said.

In her 30s, Earnest said she became involved in non-governmental organizations, trying to find in the group the feeling of being a daughter that she said she missed.

She revealed that she had tried to locate Evelyn and Vic’s remains but found nothing. This gave her a glimmer of hope that her parents could still be alive.

“We did everything. We went to Nueva Ecija and looked for the bodies… we didn’t find any remains, at all. We held out hope that it wasn’t true,” she said.

“Until 1986 we were waiting… I remember that there was a conversation like that, that they’re really gone because they would have surfaced by then if they were still alive,” she said.

Until now, they had not found her parents’ bodies.

In 2022, her mother Evelyn was included in the Bantayog ng mga Bayani’s Wall of Remembrance, joining other names of individuals who fought against the dictatorship.

As of 2023, there are 332 martyrs and heroes on the list of the Bantayog ng mga Bayani.

“I’m really proud of her being part of Bantayog ng mga Bayani. To be recognized for her heroic deeds fighting the dictatorship. May her life, and that of Tatay Ric Mangulabnan, inspire and encourage us to continue standing up for our country,” Earnest said.

Bantayog ng Mga Bayani Foundation executive director May Rodriguez said the foundation was established immediately in 1986 in hopes that it will help future generations remember what happened.

Rodriguez, however, stressed that Bantayog was only there to augment what should be done by the government.

She cited Republic Act 10368 or the Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013 which states that the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission must “coordinate and collaborate with the Department of Education and the Commission on Higher Education to ensure that the teaching of Martial Law atrocities, the lives and sacrifices of human rights violations victims in our history are included in the basic, secondary and tertiary education curricula.”

“That needs to be taught to the children. So they would not immediately be in awe of those who speak well, of those who know how to flatter. Because if they are taught well, then they can be more critical of our leaders,” she said.

The stories of Mary Ann, Len, Miks, and Earnest could be another person’s narrative.

Their resilience, grit, hope, and defiance have kept them going at a time when it was safer to stay silent and just move on. —with photography and web design by Jessica Bartolome, LDF/NB, GMA Integrated News