Because of the aches that come with age, Mang Elmer, 76, plies the jeepney route between Manila Central University and the Pasay Rotonda only twice a week—on Tuesdays and Fridays, from 5 a.m. to 11 a.m. and again from 5 p.m. to 10 p.m.

After paying the jeepney operator his share or the “boundary”, Mang Elmer takes home P500 to P1,000 a day to his wife. With a relative living with them, he said his income and his wife’s sari-sari store profits are just enough to get by.

While many people his age have retired, Mang Elmer still has to get behind the wheel daily to put food on the table. After the deadline for consolidation of public utility jeeps took effect on May 1, 2024, plying the route has become more precarious.

76-year-old driver Elmer Cordero, PISTON 6

Mang Elmer’s jeepney is one of the over 36,000 PUVs that did not consolidate under the government’s modernization program. With the ban on unconsolidated jeeps, he risked getting fined steeply and the vehicle impounded.

“Wala pa naman. Hindi pa sila handa. Anong sasakyan ng mga tao, estudyante, teachers, manggagawa?” an adamant Mang Elmer said, stressing the lack of modern jeeps and the continued need for the traditional units.

(There are not enough modern jeeps. They are unprepared. Without us, what will happen to commuters, students, teachers, employees?)

Seven years after the modernization program was introduced, jeepney drivers like Mang Elmer continue to face the high cost of modern jeepneys, the lack of route plans, and inadequate safety nets while thousands of commuters have to deal with fewer PUVs on the road.

Introduced in 2017, the PUV Modernization Program (PUVMP) required PUVs to have Euro 4 diesel engines to ensure roadworthiness and improved air quality.

The program required drivers and operators to consolidate under cooperatives or corporations, which will be given fresh seven-year franchises after they buy at least 10 modern jeepneys, mostly mini-buses.

As of May 20, DOTr records showed that 81% or 155,513 of 191,730 PUV units have been consolidated. As for routes, only 74.32% or 7,077 of 9,522 have completed the process.

Some 36,217 PUVs and 2,445 routes remained unconsolidated after the April 30 deadline.

In an April 30 Board Resolution No. 53 Series of 2024, but which was made public only in July, the LTFRB said unconsolidated jeepneys and UV Express units were allowed to operate in over 2,500 routes with a low number of consolidations.

However, the unconsolidated PUVs in low-consolidation routes are still subject to the approval of the Local Public Transport Route Plans (LPTRP).

The resolution added that authority to operate was given to PUJ and UV on low-consolidation routes, “provided that their units are currently registered with the LTFRB and have a valid personal passenger accident insurance coverage.”

Even with this relief, the public transportation sector continues to face issues that keep many operators and drivers from embracing the plan.

PUV Modernization Program, anti-poor nga ba? | The Mangahas Interviews

Based on available data from the Land Transportation, Regulatory and Franchising Board (LTFRB), a modern jeepney now costs P2.4 million to 2.6 million from as low as P1.4 million in 2017.

State-run banks Landbank of the Philippines (LBP) and Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP) have been designated as fund sources for acquiring loans payable in seven years with a 6% interest per year.

At a public hearing at the House of Representatives last year, an executive of LBP said that based on its initial study, the operations of transport entities would be viable if the cost of the jeepney is within P1.6 million to P1.8 million.

Pagkakaisa ng mga Samahan ng Tsuper at Operator Nationwide (PISTON) national president Mody Floranda believed the government was forcing them to buy expensive units when the sector could not afford them.

“Bakit kailangan namin bumili ng ubod ng kamamahal ng mga sasakyan? Noong 2017, P1.7 million lang ‘yan. Ngayon, P2.6 million na, P3.3 million iyong Class 4 na pinakamalaki. Lalong hindi kakayanin,” Floranda said.

“And nakikita namin, ang layunin ay hindi para ayusin ang ating public transport, kundi maging isang malaking business,” he added.

(Why do we need to buy these expensive jeepneys? The price has gone up from P1.7 million to as much as P2.6 million to P3.3 million for the Class 4 unit which has the biggest capacity. From what we are seeing, the goal is for big businesses to thrive and not to fix our public transport system.)

Floranda cited the case of a transport cooperative in Quezon City which consolidated in 2018 but managed to buy just one modern jeepney.

He said the cooperative did not have enough earnings to buy more modern units. The cooperative’s route was short and meant its drivers getting paid the minimum fare.

“Bakit hindi sila makakuha ng unit? Kasi hindi nila alam kung paano babayaran doon sa iksi ng ruta. Paano nila babayaran, ‘yung pamasahe nila minimum? Gawin mo nang P15, saan mo kukunin ‘yung almost P37,000 per month?”

(Why can't they get a unit? They have no idea how to pay their units given their short route. How could they pay through the minimum fare? Let’s say it’s at P15, but where will you get the almost P37,000 per month?)

Under the government guidelines, a transport cooperative is required to get at least 10 modern jeepneys in 27 months from its consolidation date and have a terminal on both ends of the route to be granted a seven-year franchise to operate.

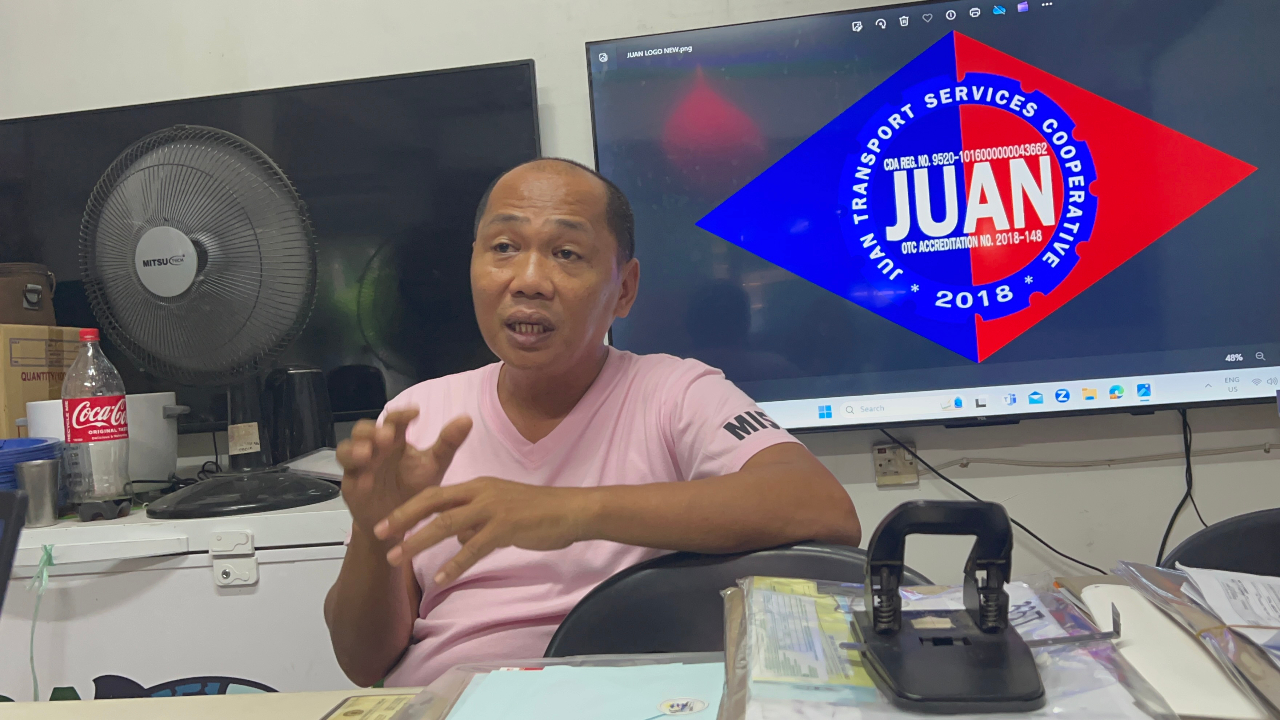

Misael Melinas, chairperson of JUAN Transport cooperative, which was formed in 2019, narrated how difficult it was to buy the pricey modern units. It took the cooperative four years before their 10 modern jeep units were delivered.

Melinas said that while their group was able to secure a loan approval from the state-run Development Bank of the Philippines for 10 units of modern jeeps in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic forcing a worldwide lockdown in March 2020 derailed their path to what was supposed to be a better life under the modernization program.

Aside from the pandemic, Melinas said that another obstacle they encountered was the government banks’ policy of requiring transport cooperatives to submit a Local Public Transport Route Plan from the local government units.

“Wala pa naman. Hindi pa sila handa. Anong sasakyan ng mga tao, estudyante, teachers, manggagawa?” —Mang Elmer, PISTON 6

Without loans to buy new units and banned from plying the routes amid community quarantine, Melinas said many PUV drivers and operators had to sell their traditional jeepneys to survive.

“Ibinalik yung folder namin from DBP. Then during the pandemic, siyempre, struggle lahat. Ang daming nawala. Sa amin na lang eh. Isipin mo, from 81 naging 60 na lang kami. Talagang hopeless kami talaga noon, hindi namin alam kung makakabiyahe pa kami,” Melinas, who was even arrested in 2017 for protesting the jeepney modernization program.

“Saka syempre, alam mo na yung, nasa bahay ka lang, wala kang pera. So, 'yun lang ang meron pang ari-arian, iyong jeep. So, let go mo to survive. Survival [mode] ‘Yung iba nga, hindi na nag-rehistro, pinakilo na lang,” he added.

(Our loan application was returned and the pandemic happened. A lot of us gave up on our jeepneys. In our case, from 81 franchises, we were reduced to 60. We were hopeless back then, we didn’t know if we could still ply the routes. Stuck at home, we had no money. The jeeps were the only property we had left. We had to let them go to survive. Others didn't bother to have the jeeps registered. They were just sold as junk.)

Melinas and his fellow members in JUAN Transport got a break when a well-financed cooperative based in Ilocos Sur offered affordable loans after the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns.

The private entity did not require a route plan for a loan. This enabled the Melinas’cooperative to finally secure the funding they needed.

Melinas said the cooperative bought 10 modern jeepneys which were delivered in February 2023.

He said that the experience of JUAN Transport, whose franchise route includes SM Fairview to Lagro Loop and Lagro to Novaliches in Quezon City, should convince their fellow drivers and operators to embrace the modernization program.

“We consolidated in 2019 but our modern units were only released last year. Hindi kami pinwersa ng gobyerno na, 'O, palit na kayo'," Melinas said.

“Ang pakay ng consolidation talaga, para lang parang malaman natin ilan ba talaga yung tumatakbo sa bawat ruta,” Melinas added.

(We consolidated in 2019 but our modern units were only released last year. We weren't forced by the government to replace our units. The consolidation is really needed so we would know for sure how many franchise holders are plying certain routes.)

JUAN Transport Cooperative Chairman Misael Melinas

Melinas then said that if not for the consolidation requirements, they would not have known that over 500 franchises previously granted by LTFRB to individual jeepney drivers and operators were already inactive.

“During the pandemic, marami nang nawalang jeep. Kaya ngayon, kung titignan mo yung datos [kung ilan ang may prangkisa], iba na siya. Pagkukulang rin ‘yan ng LTFRB” Melinas said.

(A lot of us gave up our jeepneys during the pandemic, so if you would look at the franchise holders right now, it is entirely different. That is on LTFRB.)

“Pagkukulang ng LTFRB na hindi niya in-update, pero ito na iyong way eh, iyong consolidation. Hindi naman ito katapusan ng prangkisa mo eh,” Melinas added.

(The LTFRB is accountable for failing to update the list, but consolidation is the way here. Your franchise won’t end with consolidation.)

Looking back, Melinas said that they were able to endure the birth pains and eventually thrive in the modernization program with a little help from their fellow transport cooperatives and an apparent induced change of behavior of commuters who now prefer to ride the air-conditioned modern jeeps.

“Dati, parang takot din kami kasi P2.8 million o P2.6 million Parang ang hirap. Ang laki [ng babayaran]. One year pa lang kami may modern...kami ‘yung baby ng grupo, pero, pasalamat naman kami kasi very supportive naman yung ibang mga coops, ‘yung mga nandito. Sila iyong umaalalay sa amin. Iyong mga mali nila na nagawa noon, naitatama namin sa co-op namin,” Melinas said.

(We used to be scared, too. Imagine shelling out P2.6 million to P2.8 million. That’s a lot to pay. We are only a year into this, and we thank the cooperatives before us who are helping us out so we can improve.)

Hya Bendaña – driver’s daughter, Ateneo valedictorian | The Howie Severino Podcast

PISTON’s Floranda conceded that it was possible to thrive with the modernization program, provided that the route you secured a franchise to operate is profitable.

He said the government did not know which routes were profitable, if not viable. It was already mandating modernization without finishing the route plan.

In addition, the PISTON leader said a franchise already secured to ply certain routes was no guarantee that all existing drivers would be accommodated with an unfinished route plan.

Based on LTFRB records, only 1,094 out of 1,574 local government units (LGUs) were able to submit a local public transport route plan. Of the 1,094 submitted route plans, the LTFRB approved 173 routes or 15.81%.

Of the 1,094 route plans, 205 are still under evaluation by the LTFRB, while 664 are still under revision.

“Depende sa ruta rin eh. Marahil iyong kila Misael (JUAN Transport), walang ibang 'andun rin sa ruta,” Floranda said.

(It depends on the route. It works if you don’t have a lot of competition in the route.)

This led Senator Grace Poe, the former chairperson of the Senate Committee on Public Services, to point out in one of the public hearings the folly of a transport modernization program without a route plan.

“Anong klaseng road transport modernization ang hindi tapos ang ruta," Poe said.

(What kind of road transport modernization is this which does not have a complete route plan)?

PISTON National President Mody Floranda

Floranda said that under the PUVMP guidelines, the number of modern jeepneys allowed to ply in one route was limited to 15 units at most, a scheme that would also displace a lot of drivers given that as much as 100 traditional jeepneys are deployed per route under the existing system.

“Ang tanong nga namin sa kanila eh. Paano kung ang isang ruta, meron kang 100 units of traditional jeepney? Saan mo ilalagay 85 [na drivers]? Anong gagawin mo doon sa 85 [drivers] na umaasa? Kasi labinlima lang eh,” he said.

(Our question is, where do you deploy the 85 drivers then?)

“Paano pag lumabas iyong public transport route plan tapos hindi na puede sa iyo iyong ruta? Sabi ng LTFRB, madali naman po maglipat eh. Pinag-practicean iyong kabuhayan ng tao. Gumawa ka ng programa na walang matinong pag-aaral,” he added.

(What happens when the public transport route plan is finalized and you cannot ply the route you used to ply? LTFRB said it is easy to transfer [franchise holders] to another route? So, our source of livelihood just served as a practice route for them since they did not think the program through.)

Floranda said the situation of the cooperative plying Pasig-Taguig route, which served as a pilot area for the public transport modernization program with 105 units, was a cause for concern since the said cooperative’s modern jeepney units is now down to 20 units due to a lack of earnings.

He is worried that such a case could result in a corporate takeover or the abolition of the cooperative.

“Kapag hindi nila mabayaran ‘yun, madugo eh,” Floranda said.(If they are not able to pay it, it will be brutal)

Floranda said the cooperative plying the Jordan-Quezon City Hall route had to use the funds earned by the 180 traditional jeepneys on its fleet to pay for the amortization of their 10 modern jeepney units. This means a monthly expense worth P2.8 million.

If the government wanted to modernize public transport for the common good, Floranda said it should have prioritized assistance to local jeepney manufacturers so they could produce sturdy but cheaper units costing just a little above P500,000 or the price of the traditional jeepney.

Many modern jeepneys are made by Chinese and Japanese companies.

“Hindi iyong ating ekonomiya ang pinapaunlad. Ang pinapaunlad rito, iyong mga dayuhan at mga negosyante, iyong nagsusupply ng mga mini-bus rito sa ating bansa, katulad ng Japan saka China,” he said.

(They are helping the foreigners manufacturing minibuses instead of helping our economy and local industries.)

“Ang dami-daming mga lokal na may kapasidad na gumawa… Nandiyan ‘yung Francisco [Motors], nandiyan ‘yung Sarao. Halos lahat ng rehiyon sa Pilipinas ay gumagawa ng public transport. Mas dapat ito ang suportahan. Siyempre, ‘pag marami nang gumagawa niyan, malaki ang posibilidad na bumaba ‘yung kaniyang price,” he added.

(There are a lot of local manufacturers. Francisco Motors, Sarao...there are local manufacturers in almost all regions in the Philippines. The government should support them. If they make a lot of modern jeeps, the unit price will go down.)

“Bakit hindi sila makakuha ng unit? Kasi hindi nila alam kung paano babayaran doon sa iksi ng ruta. Paano nila babayaran, ‘yung pamasahe nila minimum? Gawin mo nang P15, saan mo kukunin ‘yung almost P37,000 per month?” —Mody Floranda, PISTON National President

Floranda said that the public transport modernization’s policy of granting the franchise and the subsequent ownership of modern jeepney units to the transport cooperative or corporation was a bitter pill to swallow.

It meant those who paid for the purchase of modern jeeps won’t own the franchise.

Under the old system, the franchise to operate is granted to individual jeepney operators, and these operators own the traditional jeepney under their name.

“Wala kaming problema sa modernisasyon. Ang nilalabanan lang namin rito, eh huwag kaming tanggalan ng pag-aari. Hindi kami laban sa modernisasyon. Laban kami roon sa pamamaraan,” Floranda said.

(We are not against modernization. What we are against is the move to deprive us of the ownership of our unit. We are in favor of modernization, but we are against how it is being implemented.)

PISTON’s Floranda said that with so many uncertainties, drivers felt that the government was using them as guinea pigs to determine whether or not the program would work.

“Mahirap na paglaruan mo ‘yung kabuhayan eh, na parang pinagpa-praktisan mo. Eh ano pa ang gagawin mo kung wala ka nang unit? Paano kapag nakitang mali pala ‘yung programa? Ano pa ang babalikan mong kabuhayan? Eh ‘di wala na. ‘Yun ang kinatatakot ng mga operators,” Floranda said.

(It is as if they are playing with our livelihood...our source of livelihood is used as a practice run. What else will a driver do if he loses his unit? What if the program turned out to be a failure? What kind of livelihood will the drivers return to? We won’t have anything. That's what we fear.)

Regional director and lawyer Zona Tamayo of the LTFRB-National Capital Region (NCR) recognized the high cost of modern jeepneys but said that the government has already implemented significant steps to address this concern.

Regional Director and lawyer Zona Tamayo of the LTFRB-National Capital Region (NCR)

Since the program was implemented in 2017, Tamayo said the government subsidy for each unit of modern jeep has already increased from P80,000, to P120,000. The subsidy has reached as much as P280,000 if the bank loan will be financed by state-run banks and P360,000 if by private banks.

“When it comes to the price, we understand. But of course, we have to consider that this is a market-dictated price. Even the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), during Congress hearings, said we are not here to dictate the market price of the units. It's up to the market,” Tamayo said.

“We're also trying to talk to the manufacturers to bring down the price, and the number of manufacturers who are seeking accreditation is increasing. The Department of Transportation (DOTr) will grant them accreditation as long as they meet the Philippine National Standards as set by the DTI,” she added.

Based on DOTr records, there are at least 20 accredited manufacturers for modern jeepneys but not one sells a unit less than P1.4 million.

“On the manufacturer’s side, even for electric vehicles on public transport, we are already in touch with interested manufacturers. So we are looking at once they consolidate [under one transport entity], the demand for modern jeepneys will be established and the prices will be brought down,” Tamayo said.

The LTFRB official said that the modernization of public transport, especially jeepneys was long overdue.

“When they go to work, to school, to the market... public transport is the most widely used form of transportation and yet, this sector has been left behind in terms of upgrades, coming up with standards. The modernization’s foremost goal is really to upgrade. We have to start somewhere to elevate the experience...for the day-to-day commute to be orderly, smooth sailing and convenient,” Tamayo said.

“We want our public transport to be so efficient that even private car owners will think twice about using their cars and use public transport instead,” she added.

Aside from enhanced commuter experience, the PUVMP will professionalize the ranks of the drivers because they will only work for eight hours as provided under the Labor Code and will be receiving a fixed salary, among other government benefits and cooperative incentives, she also said.

“We looked at the routes, and there are drivers who are still on the road until midnight because there are still passengers. One shift should only last eight hours, so consolidated transport entities would need drivers for this to work. Drivers can apply for a job in these consolidated entities,” Tamayo said.

Under the current system, drivers have to compete for passengers even during off-peak hours, which translates to additional gasoline expenses.

According to the LTFRB official, the deployment of the fleet is monitored via GPS and dispatching system, ensuring that the number of modern jeeps corresponds to the number of available passengers on the road.

“There's efficiency. We will be able to maximize the capacity of the modern jeepney on a per-unit basis if we work together,” Tamayo said.

Another advantage of the modernization program is the proper maintenance of the fleet which will now be shouldered by the manufacturer of the modern jeepneys instead of the individual drivers or operators.

“Jeepneys ply the routes on a daily basis 10, 12 hours in a day. Under a consolidated transport entity, these Euro 4 powered vehicles are monitored when these units are due for change oil,” Tamayo added.

“Dati, parang takot din kami kasi P2.8 million o P2.6 million Parang ang hirap. Ang laki [ng babayaran]. One year pa lang kami may modern...kami ‘yung baby ng grupo, pero, pasalamat naman kami kasi very supportive naman yung ibang mga coops, ‘yung mga nandito. Sila iyong umaalalay sa amin. Iyong mga mali nila na nagawa noon, naitatama namin sa co-op namin.” —Misael Melinas, JUAN Transport Cooperative Chairman

Tamayo suggested that the PUVMP should be institutionalized as a law for it to be stable and sufficiently funded.

As it stands, the PUVMP is a department order issued by the DOTr in 2017.

“We want this program to have regular funding, and we will be able to establish this through a law. Modernization needs to be continuous because by 2028, the first batch of modern jeepneys will be 10 years old,” Tamayo said.

“What is modern now will not be modern by then,” she added.

Tamayo also pointed to Eleksyon 2028 when a change in the national leadership could change the public transportation police.

“But if we're able to institutionalize this through a law, it will be included as a regular budget item …We want the program to be continuous, not dependent on who is the sitting President,” Tamayo said.

“That is why we are calling on Congress to institutionalize this through the promulgation or enactment of a law that would really recognize the need to continuously improve, continuously modernize our public land transportation,” she added.

JUAN Transport’s leader Melinas agreed with the LTFRB, saying that funding for the program will always be insufficient, if not uncertain, without a law.

“Papabor sa amin [kung batas] kasi makakaroon siya ng ngipin. Iyong service contracting cost, kasama na sa national budget. Hindi kami iyong namamalimos, susulat pa kami sa Kongreso, na please, include this,” Melinas said.

(A law is favorable to us because the policy will have teeth, and the budget needed for it will be included in the national budget instead of us begging, asking the Congress, please include this.)

“Sa batas, mare-regulate mo rin iyong presyo ng mga modern unit. Ngayon, hindi po puede i-mandato [ang presyo],” Melinas added.

(And under a law, you will be able to regulate the unit price of modern jeepneys. As it is, you cannot mandate the price.

Bakit hindi makaabante ang PUV Modernization Program? | Need To Know

In the absence of such a law and lack of government funding, PISTON’s Floranda believes the traditional jeepneys are here to stay and will continue to be of use since there are not enough modern jeepneys available to ply all the routes.

Floranda also invoked Article 12, Section 11 of the Philippine Constitution which states that a franchise, certificate, or any other form of authorization for the operation of a public utility “is subject to amendment, alteration, or repeal by the Congress when the common good so requires.”

“Kaya kung sa usapin ng legal, bibiyahe ba ang mga operator [ng traditional jeepneys]? Karapatan niya bumiyahe,” Floranda said.

(In terms of legality, can operators still operate their units? He has the right to be on the road.)

Mang Elmer, a member of PISTON, said government will have no choice but to allow the old jeepneys to ply the road amid a loophole-filled modernization program.

“Ang pinaglalaban namin, hindi lang naman ito para sa driver, operator lang. Para ito sa kapakanan ng lahat. Minsan nag-uusap kami ng asawa ko. Wala naman tayong jeep, wala naman tayong pinapasukan na pabrika, bakit ka sasama [sa laban]? Pero siyempre, nakikita ko ang kalagayan ng mga naghihirap sa kalsada,” Mang Elmer said.

(What we are fighting for is not just for ourselves. It is for the benefit of all. Sometimes, my wife tells me, we don’t own a jeep, and you are not employed in a company. Why join these protests? But for me, I see the plight of the people.)

“76 years old na ako. Marami ng karamdaman sa baywang ko. Pero pagdating sa mga laban, parang sumisigla ako. Hindi kami titigil kasi maraming mawawalan ng trabaho. Hindi bale sana kung dito sa Pilipinas magpapagawa ng bagong jeep. Hindi kami tumututol sa modernisasyon na ‘yan. Ang problema, mahal,” Cordero said.

(I am 76 years old and I already feel a lot of pain around my waist. But when it comes for fighting for this cause, I get energized. We are holding the line because this modernization will mean job losses. It would have been fine if the new jeepneys were made by Filipinos. We are not against modernization, but the problem is it is too costly.)

GMA News Online interviewed Mang Elmer at a rally at Padre Faura in Manila where operators and drivers asked the Supreme Court to rule in favor of their petition seeking a temporary restraining order on the modernization program.

He said he would driver and ply his route after the protest program, which was also around the time workers and students started to go home in the afternoon rush.

Mang Elmer said he was far from giving up the fight with lots of livelihood on the line. With hundreds like him, it appears the Philippines’ King of the Road—the traditional jeepney—is not yet dead. —with design by Jessica Bartolome, LDF/NB, GMA Integrated News

In-depth special reports and features showcasing the best multimedia storytelling from GMA Integrated News.