We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

Part 1

A part-time teacher and full-time mother. A writer. A community organizer.

These are the stories of wives who shared their husbands with the country and dream of a better life not only for their families but for the people. They also share the common fate of losing their spouses to the cause, either going missing or detained, or getting killed and being declared as martyrs.

Beyond the immeasurable pain of dealing with the loss and the ambiguity of the future of their loved ones, they soldiered on – raised the family, carved their own niche, looked after one another, carried on with the advocacy.

The words of Cuban leader Che Guevarra could not have been farther from the truth, “A true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love.”

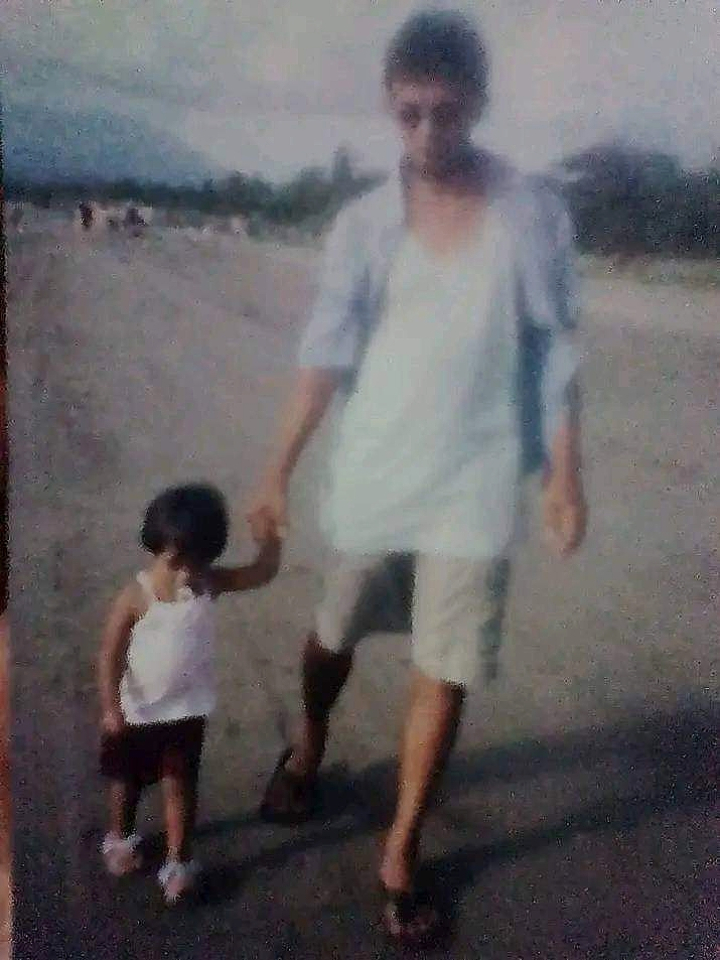

Mary Ann fell in love with a fellow activist and farmer Jonas Burgos while working for a non-government organization. Soon after, they were married and had a daughter. Three years into the marriage, Jonas, or Jay as she fondly calls him, one day left for the mall. This was on April 28, 2007. Witnesses said he was abducted by unidentified men. Mary Ann would never see him again.

“’Pag umuwi na si daddy,” Mary Ann recalled promising her then two-year-old daughter, Yumi, whenever the latter would look for her missing husband. “’Pag umuwi.”

Almost two decades have passed, but Jonas Burgos has yet to return home.

The couple has been married for three years before Jonas, then 37, disappeared after what was supposed to be a short trip to a Quezon City mall on April 28, 2007.

Night fell and Mary Ann had yet to receive word from Jonas. “I knew then, that night, that something was really wrong.”

She reached out to friends and other relatives over his possible whereabouts, but received no response.

Witnesses later claimed that armed men seized Jonas and dragged him into a parked van.

Jonas was the son of the late press freedom icon and staunch anti-dictatorship fighter Jose Burgos and Edita Burgos, a member of the secular order of the Carmelites. Mary Ann believed that his activities as a peasants’ rights advocate led to his abduction.

In a matter of hours, Jonas joined the list of victims of enforced disappearance in the country.

Under Republic Act No. 10353 or the Anti-Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance Act of 2012, an enforced or involuntary disappearance “refers to the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty committed by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which places such person outside the protection of the law.”

In its May 2017 submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review, the Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances (AFAD) and the Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance said there have been 1,774 reported victims of enforced disappearance since the first documented case in 1971.

Data culled by the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) from its central database – excluding those directly received, taken cognizance or has yet to be inputted by its regional offices – showed the cases of enforced disappearances for the following administrations: Corazon Aquino (382 cases); Fidel Ramos (95 cases); Joseph Estrada (32 cases); Gloria Arroyo (276 cases with 523 victims); Benigno Aquino III (49 cases with 74 victims).

No data was provided yet for the Duterte and Marcos administrations.

Meanwhile, data from rights group Karapatan showed that there have been 206 cases of enforced disappearance under Arroyo administration from 2001 to 2010, including the case of Jonas.

Under Aquino III from 2010 to 2016, the group noted that there were 29 cases of enforced disappearance while 20 cases were recorded under the Duterte administration from 2016 to 2022.

Under the Marcos administration from July 2022 up until December 2023, there have been 13 victims of enforced disappearance, according to Karapatan.

An activist like her husband, Mary Ann, who was 33 at the time, feared that the same fate would befall her and Yumi. Her family decided mother and daughter should temporarily live apart for their protection. Mary Ann felt she lost both husband and child in a blink of an eye.

“It really felt maddening… to secure us both, they separated us. I got separated from my daughter. So they really secured my daughter well. And me too, in another place, because the threat is still present,” Mary Ann said.

While Yumi stayed with their relatives, Mary Ann sought shelter in a safehouse with her friends. Though she wasn’t alone, she felt anxious over her husband and daughter’s conditions, resulting in loss of appetite and sleep.

Breakdowns, Mary Ann found, were also unavoidable.

“I barely slept. I couldn’t eat,” said Mary Ann. “There were times when I couldn’t help but break down.”

The uncertainty she felt following the disappearance of her husband was far from the stability and security that Jonas’ presence brought into their lives.

Mary Ann said that with Jonas’ abduction, their dreams and plans also came to a sudden halt. Early into their marriage, the two had been planning to put up a business, and had starting saving what they can set aside from their allowance.

“I really had nothing to start with. It was very difficult. I had to do all sorts of things just to keep us afloat. But, of course, family and friends were there to help out somewhat. We received help,” she said.

To support her daughter, Mary Ann resold cheese which she obtained at factory price through a supplier. At times, she also sold clothing and other used personal belongings. However, when Yumi started going to school, she knew she had to get a more stable source of income.

By a stroke of luck, Mary Ann’s friend approached her for tutoring. Word spread, and Mary Ann later became a part-time teacher at the school where Yumi was enrolled.

“Enough to survive. But it’s not really that. It’s really not enough. There are times when we really fall short because it’s not stable. I earned more from my private tutoring, but it’s not really stable, especially once the child grows up,” she said.

Mary Ann felt the big shoes to fill when Jonas disappeared.

Only Jonas could deliver the punch lines that lighten up the household. He was a good provider. He was never too busy to spend time with Yumi, who calls him “Tati,” a portmanteau of tatay and daddy.

“She was very close kay daddy niya and pag wala si daddy niya sa bahay, she’d always make me text him or call him. Tapos whenever he comes home, silang dalawa talaga mag kalaro. Nag lalaro talaga ‘yung dalawa. Magkakampi ‘yung dalawang yun eh,” she said.

(She was very close to her daddy, and if her daddy wasn’t at home, she’d always make me text or call him. And whenever he comes home, they would play together. They would always play together. Those two were buddies.)

Mary Ann knew that soon, she had to tell Yumi the truth, no matter how painful it was.

“Hindi makaka tawag or makaka-text si daddy kasi kinuha ‘yung phone niya nung mga bad guys,” Mary Ann recalled. “Yung si Tatty mo kasi kinuha ng mga bad guys kaya hindi din siya makauwi agad. And we are trying to look for him.”

(Your daddy can’t call or text us because his phone was taken by bad guys. Your tatty was also taken by bad guys so he can’t come home yet. And we’re trying to look for him.)

Until now, Mary Ann said she was still haunted by the look of fright and denial on Yumi’s face.

For the first two months, Yumi would repeatedly ask her to call or text Jonas. Mary Ann would repeat her explanation about the bad guys. These, she said, were the hardest moments to deal with.

Until one day, Yumi nonchalantly approached her mother and said, “We will look for him.”

“I replied, ‘of course’,” Mary Ann said. Hope springs eternal in heart of a child.

“Sana nakikita ako ni Tatay.” This, Mary Ann said Yumi would often utter.

She would record on video and take photos her every school performance and the important events in the family, and assure her daughter, “we will show this to your Tatay when he comes home.”

“Those moment are one of the hardest to face because you know they will keep on repeating, she will continue hoping for her Tatay’s return,” she said.

“It has to be like that. We still look for him. Because if we don’t do that, we may lose our hope. So we tried to remember everything and tried to celebrate every occasion as if he was still with us,” she added.

For around five years since Jonas’ disappearance, Mary Ann said she would still see her husband in her vision.

“‘Yung first years— four to five years nung incident, halos parang nakikita ko pa sa vision ko. Yung naglalakad talaga, ‘yung dadating siya doon at bubuksan niya yung gate. O kaya yung doon sa park, nakikita namin na nag lalakad siya sa pathway,” she said.

(For the first years— four to five years after the incident, it’s like I would see him in my vision. As if he was walking, as if he just arrived and would open the gate. Or at the park, and I would see him walking on the pathway.)

Like a fresh wound, Mary Ann said the pain of losing Jonas in such a circumstance never goes away. It only teaches one to live with it, she said.

“Hindi lang ‘yung mismong victim ang tino-torture mentally, emotionally, economically, spiritually. Lahat na. Hindi lang ‘yung victim mismo ang tino-torture ng ganon kung hindi lahat kami tino-torture ng ganon, continuously since then. Hanggang ngayon,” she added.

(It’s not only the victim who is being tortured mentally, emotionally, economically, spiritually. Everything. It’s not only the victim who is being tortured but everybody, continuously.)

After Jonas’ abduction, Mary Ann would remain inconspicuous for several years for her safety.

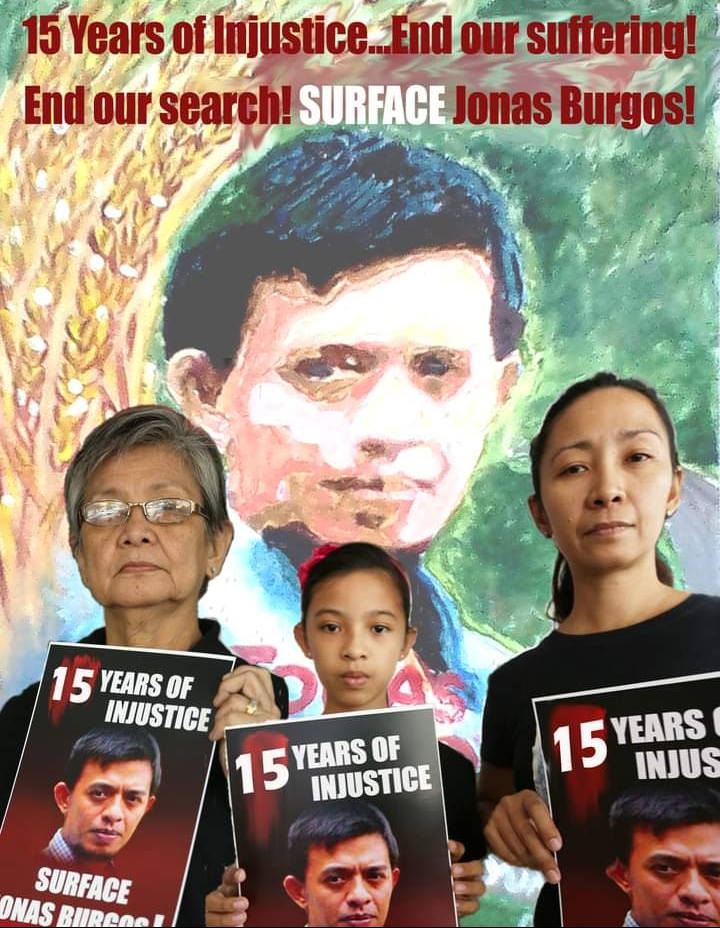

Jonas’ mother, Edita, took the front lines and sparked a national search for her son that brought her to various local and international fora, different courts, and communities of families similarly suffering from the cruel inhumanity of enforced disappearance.

A devout Catholic, Edita had said in an earlier interview that she relies on her faith to help her deal with what has happened.

“Ang mga mukha ni Jonas ay nagpapakita na marami pang nawawala. Si Jonas lang ang nasa pahayagan ngunit marami pa ang biktima. Hanggang nagpapatuloy ang pagdukot, hindi titigil ang Burgos family,” she had said.

Remembering Jonas on his 16th year of disappearance last April 27, 2023, Edita said in a social media post showing his photograph, “16 years ….we will search and love forever.”

It was only six years after the abduction when Mary Ann surfaced in the public with a video message for her husband that they will never stop looking for him.

A year before, she recalled she dreamt of Jonas while she was feverish and lying in bed.

“That one time when I was gravely ill, between being awake and asleep, he walked in the bedroom and sat by my side. We hugged each other. I laid my head on his lap. After a while, he said, ‘I have to say goodbye now’,” Mary Ann said.

“I knew in my heart what it meant. I told him, ‘just a few more minutes.’ He did give me a few more minutes. Then, he stood up, walked towards the door, smiled, and disappeared,” she added.

After this, Mary Ann said that she no longer dreamt of him as a captive. Instead, she said she would hear his voice offering her solace and companionship during moments of solitude.

“What brought me peace is the thought that no matter the distance between us, no matter the state we're in, our love and our vows to one another are what hold us as a whole and not as separate individuals. Thus, we are eternally together,” she said.

“It has to be like that. We still look for him. Because if we don’t do that, we may lose our hope. So we tried to remember everything and tried to celebrate every occasion as if he was still with us.”

The legal battle continues as Jonas’ 17th year of disappearance nears.

In 2011, a complaint was filed before the Department of Justice (DOJ) against state forces who were allegedly involved in his abduction.

In September 2013, the DOJ recommended the filing of criminal charges of arbitrary detention against then Major Harry A. Baliaga Jr. Baliaga belongs to the Bulacan-based 56th Infantry Battalion. The other respondents in the complaint were cleared by the agency.

In 2017, a Quezon City court acquitted Baliaga of the charges filed against him. Currently, Mary Ann said their motion for reconsideration on the acquittal of Baliaga is still ongoing.

Mary Ann confirmed that a documentary about Jonas Burgos will be released in December 2024. The documentary is made by his brother, JL Burgos.

“In Jonas’ case, not all of the evidence was made public, the evidence that would defy the statements of the military,” said Mary Ann. “Maybe through this (documentary) they would see more clearly who Jay is –as a person, son, brother, nephew, uncle, husband, and comrade.”

Mary Ann said that she and Yumi are also considering launching a YouTube channel to extend support to families who are in similar situations. She said doing so would somehow help relieve the pain.

“You have to think that you are not alone, because the truth is you’re not,” she said, adding that a community of wives, daughters and families is there to make the burden lighter.

Now 50, Mary Ann said, “We have to hold hands together to get through this. Think that if something so tragic and so cruel happened, that this is not the end.”

“Your loved ones who were taken from you, they are always with you. They would only be gone if you stop remembering. Never forget, so they will always be with you,” Mary Ann said. —with photography and web design by Jessica Bartolome, LDF/NB, GMA Integrated News