Photos by Danny Pata | Additional photos, visuals, and design for web by Jessica Bartolome

June 28, 2024

Hundreds of inmates or persons deprived of liberty are released frequently, now more than ever with the Marcos administration’s plan to decongest the country’s prison and penal farms. But after spending some time of their lives in detention, how do these individuals pick up where they left off?

WHEN 'MARIA' WAS ARRESTED and subsequently released from her 10-month imprisonment over illegal drugs, she all but disappeared in the eyes of her loved ones.

“My family thinks I’m a bad person,” she explained, teary-eyed.

The 48-year-old recalled that before her apprehension, she would be the first of her siblings and cousins to show up at the first sign of trouble, always ready to give a helping hand.

“I feel upset with them. Because when they were in trouble, I was the first to be there,” said Maria (not her real name). “My husband knows that. If anyone is in trouble, whether it be friends, if someone’s in the hospital or if they died, if something needs to be processed, I’m there.”

Her detention, however, led her family to distrust her, so much that they did not reach out to her when her sister was hospitalized due to cancer in February 2023.

“They treat me like I shouldn’t be trusted even if they know that I can help. Even when my sister was in the hospital for breast cancer, they didn’t trust me. Especially with money,” she lamented.

Maria added, “It was as if I didn’t exist.”

Dozens of persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) attend a culminating program at the New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa City on April 20, 2023, before their release. DANNY PATA

Prof. Raymund Narag speaks to GMA News Online

According to international criminal justice expert and Southern Illinois University Professor Raymund Narag, some persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) have difficulty returning to society due to stigma and public perception despite their good behavior while in detention.

“Once they are released, they already have an identity as an ex-con and they can’t be understood by the public. They have difficulty finding livelihood, sometimes they are ostracized, and people can’t see the sacrifices they made inside,” Narag said. “What people see is their status as an ex-convict.”

Narag said it would be difficult to get rid of the stigma, and referred to this as a “continuing punishment.”

“Sometimes there are the so-called continuing punishments like questions such as have you ever been accused of a crime, have you ever been arrested for a crime, have you ever been charged and convicted of crime when you apply for work,” he said.

He urged former PDLs to understand the public’s perception, saying such was natural.

“How do you overcome that is the better question. So work hard and study if you can still study,” advised Narag. “Return to the families that you lost and become a good parent to them because eventually, that will transform the reputation that you have, not only in the family but in the community as well.”

And Maria tried. When her sister passed away, Maria chose to contribute in secret. She made arrangements and rented a van, allowing her sister’s friends and other relatives who live in Quezon City to be able to attend the wake in Bulacan.

But instead of gratitude, Maria was greeted with wariness, and she felt as if her family was indirectly pushing her away.

“Oh, why are you here? It was like they were asking that. Because they didn’t expect me to be there. I told them I was there as their sibling,” she said.

For Maria, the attitude of her siblings and relatives stemmed from their belief that she committed the crime she had been charged with instead of believing that she didn’t.

In front of her children and neighbors, authorities arrested Maria in September 2021 for drug trafficking. Though she admitted to using illegal drugs, she denied participating in the drug trade, saying she only pleaded guilty to the charge in order to get a shorter sentence upon the advice of her friends.

Only two of Maria’s siblings visited her while she was in jail, but they never returned.

“My family tried to contact my siblings but they never reached out,” said Maria. “At first, they said they would help us, but it seems as if they just left my husband hanging.”

Despite the lack of support from their other relatives, her spouse and children struck by her side. Though her family visited daily, they were unable to meet and talk to each other because of the COVID-19 protocols being implemented at the time.

Instead, they wrote each other letters. In one of these letters, Maria apologized to her children for her detention, saying she understood if they were ashamed of her.

The reply she received bolstered her spirit in the coming months.

“They told me, mama we are not ashamed of you. Some people asked us, your mother is imprisoned? But we didn’t have any thoughts of being ashamed of you,” she said.

Her children did not remain unaffected by the situation and Maria found that they had grown protective of her after her release.

“They would be very worried if I would return home somewhat late. Because they don’t want me to be arrested again. They don’t want me to end up in the same situation,” said Maria. “Because they also don’t want to return to that kind of situation. If I had a hard time in detention, they also had a hard time outside.”

The lack of involvement from her siblings in the ordeal, however, led bitterness to develop on the part of her spouse and children. When her father passed away in December 2023, Maria said her family only attended the last day of the wake and her husband only stayed for a short time.

“My family can’t accept how my siblings treat me. When my father was still in the hospital, they treated me as if I was a helper. That’s why they are mad,” she said.

Due to this, Maria also resolved to treat her children and spouse as the only family she has.

“I accept how they treat me… because I can’t force them to treat me well. I can’t do that to them. I can’t force myself onto them, that they should treat me well. Because I was detained,” she said.

As part of the administration’s efforts to decongest the country’s prison and penal farms, the Bureau of Corrections (BuCor) has released a total of 12,053 PDLs as of February 2024.

Meanwhile, 4,600 PDLs have been transferred out of the New Bilibid (NBP) Prison as of May, leaving 10,900 more to be transferred to other prisons and penal farms for 2024.

The BuCor supervises the NBP in Muntinlupa, the Correctional institution for Women (CIW) in Mandaluyong, the Sablayan Prison and Penal Farm in Occidental Mindoro, the Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm in Puerto Princesa City, the Leyte Regional Prison in Abuyog, the San Ramon Prison and Penal Farm in Zamboanga City, and the Davao Prison and Penal Farm in Davao del Norte.

For the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), around 80,000 PDLs have been released through its BJMP’s Paralegal Program as of December 2023.

PDLs who are sentenced and found guilty in court are sent to BuCor facilities while PDLs who are still undergoing trial or are sentenced for less than three years are detained at BJMP facilities.

Persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) are crammed inside a cell at the Muntinlupa City Jail in this photo taken on April 4, 2024. The city jail currently houses 922 PDLs, way above its original capacity of 41. MAKI PULIDO/GMA Integrated News

Narag, who is also a consultant of the Department of Justice, explained that PDLs would create new roles or identities inside facilities as a coping mechanism. He said some PDLs “adapt” while others are “prisonized.”

He said that PDLs who adapt will try to fit in with the culture of the facility to avoid becoming a target without compromising their values.

“There are many inmates like that who adapt once inside the facility, but once they are released, they can easily return to how they were. They can shed off the influence. They won’t boast about their tattoo, they won’t boast about their status inside,” he said.

However, other PDLs become prisonized where they fully integrate into the culture of the penal farm and forget their previous identity, according to Narag.

“The PDL stayed a long time inside and got a tattoo, his identity became a Sputnik gang member, and that became his mantra. I am Raymund Narag, a Sputnik gang member, and a drug addict who sells drugs. Once I am released, what will become of me?” Narag asked.

“I will look for my fellow Sputniks, I will look for what I learned, for my friends inside, and may even become part of the drug trade.”

This is why he advised the government to hold programs for PDLs two years before they are set to be released.

He said authorities must inform the families of PDLs of the latter’s return, find possible employment for the PDLs, and teach them how to refrain from caving to peer pressure.

“How to say no to friends who are offering drugs. How to say no to friends who are urging you to commit criminal activities. Because that is easy at first. In the first six months, the key is the family. Everyone is still excited,” Narag explained.

“But after six months, when you need employment and you want to go outside, you will go to your friends who know you have been released. They’ll urge you, ‘hey, you missed this. Let’s drink.’ If you are weak-willed, you will forget the difficulties you faced in prison and you will return.”

THIS WAS THE CASE OF 'JOHN,' who found it difficult to resist temptation after he was released.

Now living alone in a two-story house in Pangasinan and decades since his detention in the 1990s, the 50-year-old admitted that he had found it easier to be on his best behavior when he was still confined.

“You are safe in Iwahig because it’s up to you if you will be good. You’re monitored there by employees. Riots and chaos are forbidden,” said John (not his real name). “Here, you can do anything at any time. You can disturb others and you can be disturbed because it’s open.”

John was convicted of murder and spent around 11 years behind bars, seven of which was spent at the Quezon City Jail while his trial was ongoing and the other four at the NBP and Iwahig after he was sentenced.

He was released on parole after exhibiting good behavior, and John had to report to authorities for at least three years before he could obtain his certificate of Final Release and Discharge.

Some 154 persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) received their certificate of discharge from the New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa City on January 23, 2023, as part of the government's jail decongestion program. DANNY PATA

To his own disappointment, his good behavior did not last and he found himself again involved in a bad group and vices, such as excessive drinking.

“My stubbornness returned and I became involved again,” he said. “I became involved in vices, and of course, I also thought about doing bad things.”

John attributed his downward spiral to a “barkada” or a group of friends.

“I became involved again. A group. There’s really temptation in groups. You can’t avoid it,” John said. “You’re the only one who would be able to control yourself. That’s what I was thinking. I would force myself to avoid temptation.”

This isn’t the first time that John had friends who he said led him to a bad path. According to John, the incident that led to his incarceration started with his friends when he was in his teens.

“I went down a bad path,” said John, restless and uneasy as he recalled the circumstances that changed his life. “I killed— there was an accident involving somebody."

It happened during a Christmas party when he was 19 years old, though he could not remember the exact year. He and his friends had been drinking when a fight erupted.

“It became chaotic. I was only supposed to prevent the fight but I became involved too. I couldn’t help but try to pull my friend back. And then the security did something, and so did I,” said John.

Once detained at the Quezon City Jail, John felt as if the lack of visits from his group was a wake-up call. What he thought was a deep and life-long friendship turned to ashes when all his friends went into hiding, leaving him to shoulder all the blame.

He was later transferred to the NBP, a change he initially feared but later welcomed.

“It was easier in Muntinlupa,” he said. “It was still scary but it’s up to you if you will do something. It’s not like in jails where it was really difficult. You will die of sickness there.”

In contrast to the jail where food was scarce, John said food was more available at the NBP. He was also able to cook for himself in his “kubol” or booth.

After serving years in the NBP, he was transferred to the Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm in Palawan, where he stayed for three to four months before he was released.

According to John, the first thing he did was to go home to his family in Manila. There, he said he worked in the fields of construction and electrical work.

When he again found himself involved in vices, it was his sister, Anne, who suggested he move to Pangasinan to watch over her house. He said Anne “sacrificed a lot for him” and it was her who would often send him money and food while he was imprisoned.

Anne and his siblings later become his inspiration to change his life.

Now, John watches over the house, which he and his family would often rent out to tourists. He is currently unemployed due to old age. He said he receives allowance and support from his family.

“I want to be able to help my siblings.”

BuCor Director General Gregorio Catapang Jr. speaks to GMA News Online

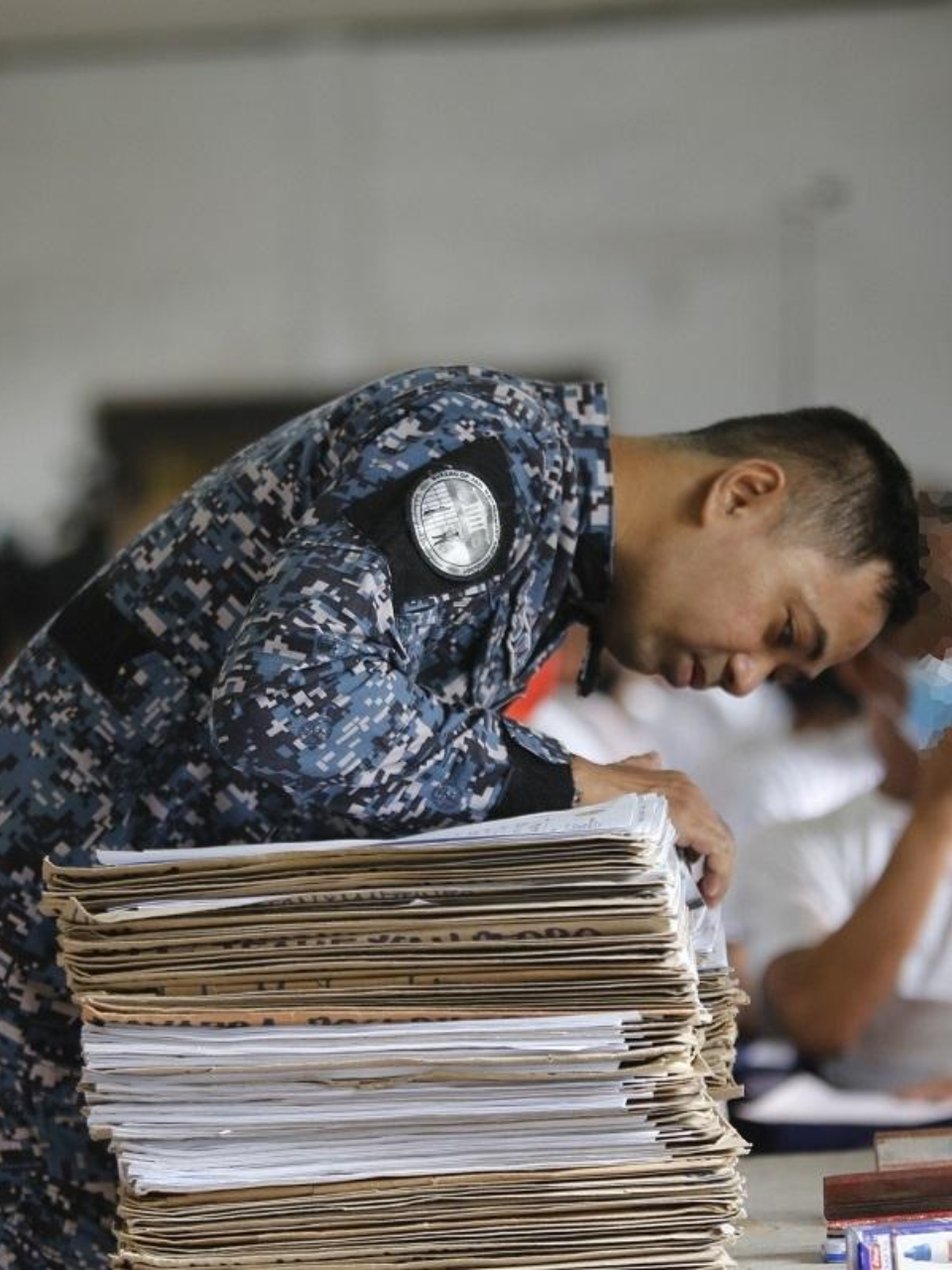

BJMP personnel arranges the records of persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) who were freed after completing their sentences during a ceremony at the Manila City Jail on December 8, 2023. DANNY PATA

BuCor Director General Gregorio Catapang Jr. said they are seeking to implement programs that would give PDLs livelihood and employment once they are released.

One such program is the establishment of BuCor’s eco-zones. The agency signed a memorandum of agreement with the Philippine Economic Zone Authorities in January to identify possible zones within the penal farms of BuCor.

The zones may be used for food security and climate change adaptation.

“Those who are no longer accepted by their families or are not yet ready to be accepted can be absorbed into our workforce,” Catapang said.

Meanwhile, as part of their reformation and rehabilitation, PDLs are given opportunities to learn skills that may help them once they are released.

“They want to develop skills so they can learn how to sew, how to make decorations,” Catapang said. “In the same manner with the males, they want to learn skills on how to be farmers, how to be laborers, or how to make hollow blocks, and how to be welders.”

PDLs can also choose to get an education while those who were involved in drugs will undergo rehabilitation.

Jail Chief Inspector Jayrex Bustinera speaks with GMA News Online

For his part, BJMP spokesperson Jail Chief Inspector Jayrex Bustinera said the BJMP has an education program and drug rehabilitation program, among others.

Bustinera said that 70% of those detained at BJMP are drug cases, most of which will be released back to the community through plea bargaining. For continuity of their rehabilitation, former PDLs are referred to community-based rehabilitation in the barangays that they will be released to.

According to Bustinera, the BJMP has also signed a memorandum of agreement on a unified aftercare program, where all agencies of government as well as local government units agreed to accept former PDLs who are looking for employment.

Both Catapang and Bustinera said they conduct classification and risk assessment for PDLs who are about to be released. Under the assessment, authorities will identify what a PDL needs once they are back in society.

“There will be a pre-release assessment where we find out what they should be referred to. For example, should it be education so they can finish their studies, livelihood, employment, or drug rehabilitation,” Bustinera said.

"THAT'S WHAT WE LEARNED INSIDE. THERE ARE MANY WAYS TO LIVE."

Years ago, 'Lyra' (also not her real name) and her aunt turned to drug trafficking in order to provide for their family. Lyra was a single mother of a two-year-old and the parental figure of her cousins, nieces, and nephews, all of whom were without jobs.

She knew that they were treading the wrong path, and it was this that led them to accept their arrest in 2009.

“I was afraid because I had a child. What would happen to her? That was what I initially felt. But what can I do?” said Lyra. “I didn’t have a choice. I couldn’t change my decisions. We were already there. Even if I regret everything, I can't do anything anymore. And my child would suffer because she would be left with someone else.”

Months later, while detained at Camp Karingal, she was visited for the first time by her daughter and her friend, who became her daughter’s guardian.

Unbeknownst to Lyra, that would be the last time she would personally see her child.

“It had been a few months already at the station, Camp Karingal, before I saw my daughter again, before I hugged her again. And that was also the last time,” she said, adding that her daughter’s guardian took her to the province without telling her.

Lyra, however, clarified that she didn’t resent her friend for it.

“She was the one who took care of my daughter. As a mother, do I have any right to be mad at her for it? My daughter was able to study. Even if I didn’t know this while I was detained. I found out after I was released,” she said. “I’m already happy with that. I couldn’t contribute anything.”

Some persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) walked out of the New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa City on December 19, 2022, as part of the 118 released amid the government's jail decongestion program. DANNY PATA

Some 154 persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) received their certificate of discharge from the New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa City on January 23, 2023, as part of the government's jail decongestion program. DANNY PATA

According to Lyra, it took her years to adjust to life in Camp Karingal. At first, she said was happy with whatever she had been given and wouldn’t make an effort of her own.

Lyra and her aunt spent six years in Karingal before they were moved to the CIW, where they spent four years.

There she learned bead-making and it became her source of income.

She said she and her aunt would sometimes dream of life outside the prison.

“My aunt and I would tell each other that once we are freed, we would change things. Because she also left behind her child. So we needed to make sure that once we were released, we wouldn’t return to the drug trade. We made plans on what we could do so we wouldn’t return to that,” she said.

However, when their appeal was granted in 2019 and the chance to leave came, Lyra didn’t want to.

She was afraid of returning and finding that there was nothing for her. She said she had no news of her daughter, no idea where to go, and no idea what to do. She felt as if she wasn’t ready.

According to Narag, this is a common reaction as there was already a “set way of life” within the facility and the release would be a “disruption.”

“It’s very common that you already have a set way of life and you will readjust once you are released. And the readjustment creates a sort of thinking that maybe you want to stay,” Narag said. “But they are only saying that because they are about to go free. In reality, they really want to go.”

For Lyra, she felt numb throughout the process of leaving. But she later found herself “very happy” once outside.

“I told myself I could see my daughter again. And that’s the first thing I did. I looked for her on social media.”

Despite finding out where her daughter went, Lyra chose to make a living for herself first. She applied as a helper but was unable to return due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lyra then made use of the skills she learned during detention and started selling items made from beads. She also has a sideline as a traffic surveyor.

When she felt that she had earned enough, Lyra reached out to her daughter on Facebook. The first thing her daughter asked was if Lyra was her mother.

“I cried because she changed so much. She was already a teenager, and I didn’t see it happen,” she said. “I couldn’t stop talking with her, until it reached a point where she started getting annoyed. I would call her all the time.”

126 persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) were released on the Philippines' Independence Day this 2024. BUREAU OF CORRECTIONS

Circumstances, however, prevented them from meeting again.

“I couldn’t go through with my visit because of the pandemic… and then after the pandemic, I formed my own family,” sair Lyra. “She told me, don’t worry mama, I will go to you. Even if you can’t go here yet. I’ll go to you.”

Lyra, meanwhile, said she was no longer afraid. When she previously could not look into people’s eyes due to shame, she now felt that she had proven she has changed.

“They know the reason why I did what I did. But at least they know that since I was released, I turned my back on that. I changed,” she said. “That’s why I’m no longer afraid. Because they can’t say anything about me anymore. I can look at them now. I can walk straight now.”

She added, “Just because you were detained doesn’t mean you will be shunned forever... Just hold on. Hold on until all the hurt has passed.” —RSJ, GMA Integrated News

In-depth special reports and features showcasing the best multimedia storytelling from GMA Integrated News.