Plastic has become an important part of our daily lives. From housing our personal care products to ensuring food doesn’t go to waste. It’s even present in the clothes we wear, and sometimes, in our skincare. The material is so durable that years after it is discarded, it remains ever present in our lives, accumulating in our environments. How do we manage?

Every morning for more than two decades, Mang Danny goes out to fish in the waters of Manila Bay. He starts his day early in the hopes of filling his bucket with fish before the midday sun gets too hot.

His three-year-old non-motorized boat takes Mang Danny to his usual fishing spot in about 30 minutes, and when he comes up with nothing, he moves to another spot.

Among his gear are an oar, a net that’s seen better days, and these days, an empty sack as well.

The sack isn’t so much for the fish as for the growing amount of plastic waste that’s become part of his daily catch.

When Manila Bay is generous, it gifts him a variety of harvest: Bangus (milk fish), Tilapia (cichlids), Banak (sea mullet), hipon (shrimp), dilis (anchovies), and so much more.

But since 2004, the sea has been more surprising than it is generous. The fisherman, who has been living in Baseco for 40 years, has also been catching plastic waste. In fact, there are days when all he could catch is plastic.

PHOTO: Jessica Bartolome

It would be a real problem if Mang Danny wasn’t smart enough — or agile enough to pivot from fisherman to garbage collector and back again, depending on what the sea gives him.

“'Pag walang isda, nangangalakal ako,” he tells the Digidokyu team one December morning, as he caught a piece of plastic waste. “Dinadampot ko ‘to kung walang isda. Ito ang kinukuha ko.”

[When there is no fish, I trade plastic garbage. I pick them up when there is no fish.]

He’s made good with the change, he says, because he can trade these pieces of plastic for a few pesos, enough to buy rice for the day.

When the sea coughs out more waste than fish, Mang Danny heads back to his Baseco home, cleans his ware, and sells them. When the sea gifts Mang Danny fish, his next steps will depend on the quantity of his catch; when there’s a lot, he goes to the market to sell them. When the sea is not that generous, he goes home with what will be his family’s dinner.

According to Mang Danny, Manila Bay was a lot more generous in the ‘90s, when he would catch so much fish, it could easily fill up his entire boat.

At present, a good day means catching two kilos of fish. He considers himself lucky with even just a bucket of fish.

And as for plastic, “talaga hindi na mawawala yan dito. Talaga may plastic eh,” he said, resigned. “Talagang hindi mawawala 'yan.”

Says Nazario Briguera, spokesperson of the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DA-BFAR), “pollutants like plastics undermine the integrity of our marine environment, the very source of livelihood of our fisherfolk.”

“The BFAR urges the public to observe proper waste disposal,” he added.

Plastic pollution doesn’t just occur on the surface of the ocean. In 2021, Doctor Deo Onda became the first Filipino to reach Emden Deep, the 3rd deepest part of Planet Earth. At a depth of 34,100 feet, he famously mistook a floating piece of plastic for a jellyfish. His finding echoes the alarming discovery of plastic waste at Marianas Trench just a few years before.

"That's one thing that really shocked me," Onda said in Filipino back then. "The plastics we saw aren't broken down. That's how resistant and durable they are."

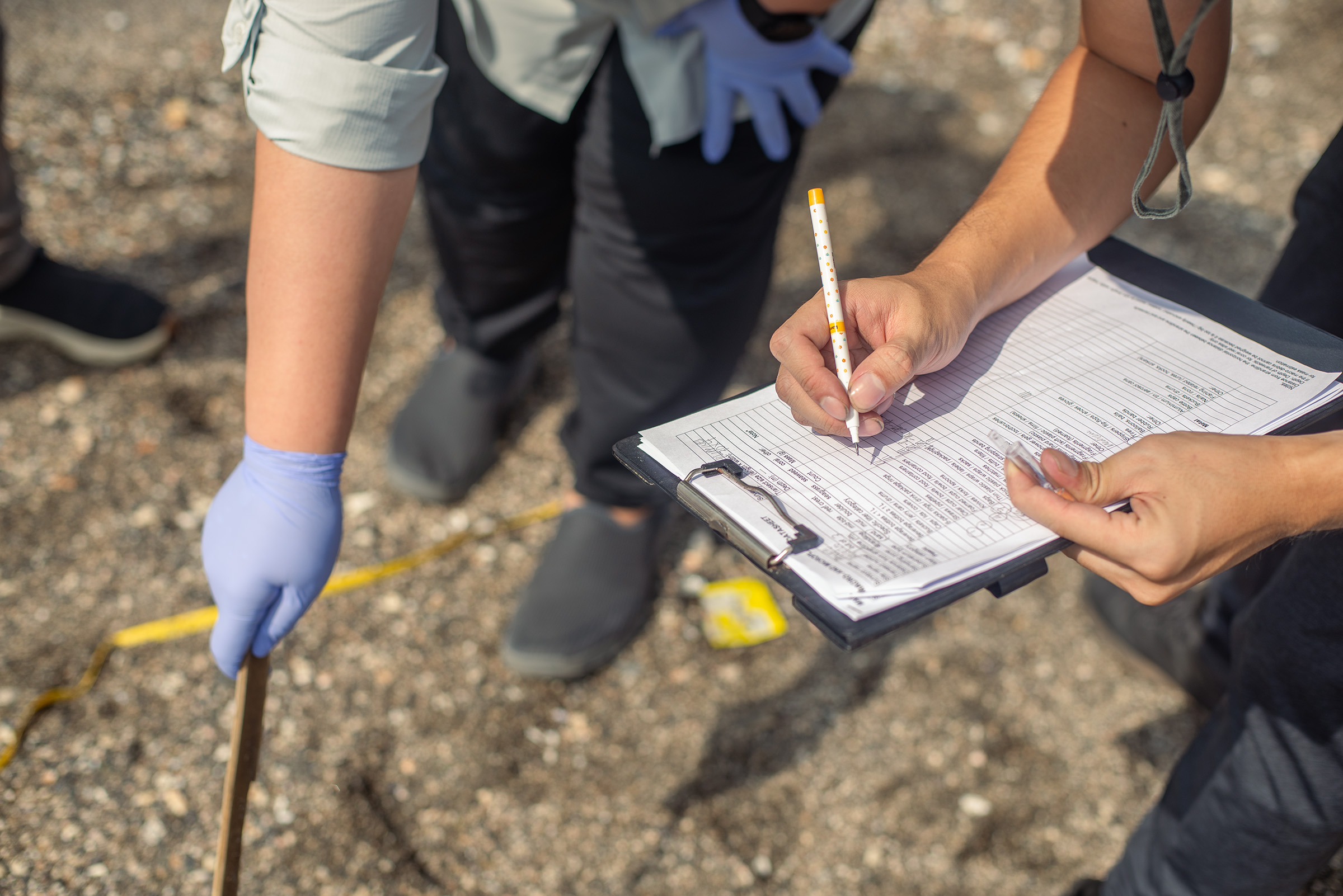

The following year, Onda became the Project Leader of PlastiCount Pilipinas, a DOST-funded project under the University of the Philippines Marine Science Institute (UP-MSI) that not only aims to count and track plastic pollution across the country but to also put it in a database and have it available online for better plastic research and to guide policymakers as well.

PlastiCount Pilipinas’ online portal features the Philippine's first interactive plastic pollution tracker that tells you how much plastic pollution is observed in a particular area in the country.

“The goal is really to have that data translated into policy,” Onda tells DigiDokyu.

GMA's Lilian Tiburco with PlastiCount Pilipinas' Deo Onda. PHOTO: Jessica Bartolome

In the two years PlastiCount has been around, Onda and his team of scientists from MSI have observed three crucial things about plastic pollution. The first echoes what he saw at Emden Deep: Plastic is everywhere.

“Sa pinakamalayong lugar, pinaka-isolated na mga lugar na wala nakatira, kahit mismo sa pinakamalalayong isla ng Kalayaan sa Pag-asa, lahat ng lugar na napuntahan namin, may plastic,” Onda said.

[In the farthest and in most isolated places, even in the farthest island of Kalayaan in Pag-asa, all the places we’ve been to has plastic.]

Second, plastic knows no boundaries. “Kahit isang lugar lang ang nagpapakawala ng plastic, yung mga plastics na yun ay pwedeng dalahin ng agos, ng tubig, ng hangin, papunta sa ibang lugar,” Onda continued.

[Even if there is only one place that releases plastic, that plastic can turn up elsewhere or everywhere thanks to the water and to the air.]

And finally, the places with the most plastics are in the mangroves, which could mean mangroves are doing a good job at preventing plastics from entering the ocean. But for Onda, it speaks volumes about the effects of plastics on environments like mangroves. “Mataas yung risks, mataas yung vulnerability, mataas yung posibilidad na sila yung pinakamaapektohan dahil sa kanila nag-iipon."

[The risks, the vulnerability, and the possibility are high that mangrove environments will be affected because they trap and collect plastics.]”

Effects of plastic pollution on the environment has become a constant fixture in the media, with plenty reports about dead marine life necropsied to find plastic in its stomach. In 2019, the DA-BFAR conducted a necropsy on a dead Cuvier's beaked whale in Compostela Valley and found 40 kilograms of plastic garbage inside its stomach.

The previous year, it was a 14-foot butanding that washed ashore Tagum City, dead from plastic ingestion.

"Ang plastic, pag pinakawalan mo sa karagatan, marami siyang pwedeng makasalubong. At sa bawat nakakasalubong niya, pwede din siyang magkaroon ng negatibong epekto,” Onda said.

[When you release plastic into the ocean, it can encounter a lot of things. And for every encounter, it can have a negative effect.]

“Pwede siyang pagkamalan na pagkain,” he continued, explaining organisms like sea weed can attach itself to plastic, and deceive fish that naturally eats sea weed. “Kapag nakain ito ng isda, maraming pag-aaral na nagsasabi na pwede siyang mag-cause [ng pagkamatay] ng isda. Pwede din silang [mag-cause ng] indigestion,” Onda continued.

[Marine life can mistake plastic as food. When a fish ingests plastic, there are many studies that now say plastics can cause its death. It can cause indigestion.]

It could be that bacteria attaches itself to the floating piece of plastic and once eaten, can cause illnesses to the fish that eats them. “Pwede ito maka-apekto sa kanilang kalusugan. At yung isda mismo ay pwedeng mamatay (It can affect its health and the fish can die),” he said.

“At the end of the day, bumabalik din sa atin 'yung mga tinapon natin.” —Doctor Deo Onda, Project Leader, PlastiCount Pilipinas

The problem extends to humans, because we eat fish and other seafood. A study done by UP MSI confirms the presence of microplastics in oysters caught across the Philippines.

“Nag-test ng mga 200 to 300 na talaba galing sa iba't ibang parte ng Pilipinas at 100% o lahat doon ay positive merong microplastic,” Onda says in a DigiDokyu video. “So, ganun na kalawak 'yung polusyon. At na-intake na din natin, 'di ba? At 'yun 'yung nakakabahala. At the end of the day, bumabalik din sa atin 'yung mga tinapon natin.”

[We tested 200-300 oysters from different parts of the Philippines and 100% of them tested positive for micro plastic. That’s how far-reaching the pollution is. We intake these oysters, that’s the disturbing party. At the end of the day, the garbage we throw out comes back to us.]

Besides, microplastics is already present in Metro Manila air, which can easily be inhaled.

In a Need To Know video, Dr. Hernando Bacosa of the MSI - Iligan Institute of Technology, who with his team of students discovered microplastics in Metro Manila air, warned, “ang ating katawan ay walang kakayahang tumunaw o mag-digest ng microplastic. Puwede siyang maging vehicle ng bacteria, virus, heavy metals na pwedeng mag-cause ng cancer.”

(Our bodies don’t have the capacity to digest microplastics. Plastics can be a vehicle for bacteria, virus, heavy metals that can cause cancer.)

While exposure to plastic — whether through ingestion, inhalation, or skin contact — presents a host of health risks, Malcolm Hudson, an associate professor in environmental science at the University of Southampton, told The Guardian we shouldn’t panic too much about our exposure to microplastics because “we’ve evolved enough to deal with inhalation and ingestion of impurities.”

A 2017 study by Joana Correia Prata published on ScienceDirect shared various ways our bodies can naturally clear itself of microplastics. These include simple things like sneezing, or having mucus as a barrier that catches pathogens, irritants and other foreign particles; as well as complex processes like phagocytosis which is among body's defense mechanisms that features a certain type of white blood cell capturing, killing, and removing pathogens.

Meanwhile, a 2022 study also published on ScienceDirect says micro- and nano- polymers may be excreted through urine and feces, when they pass into small intestines through the bile.

Instead of worrying, Hudson recommends devoting that energy into helping stop the mounting plastic pollution. “If the environment continues to get more contaminated, I think you have got potentially a harmful issue,” he said.

PHOTO: Ian Christopher Cruz, Macky Caroro

Crispian Lao is the son of an owner of a plastic factory in Manila that used to manufacture toys. Sometime in the early 2000s, he attended a waste management training in Japan and “even before all this noise on plastic,” he and bunch of other guys from the local plastic industry saw the problem.

“As early as 2004, we were starting to look into that,” Lao tells GMA News Online over Zoom.

“Maybe we were visionaries at that time,” he considers. “We were seeing a potential issue on plastics and we wanted to address it.”

In 2010, he was elected the president of the Plastic Association and in 2014, he established the the Philippine Alliance for Recycling and Material Sustainability (PARMS). Lao would go on to become a commissioner and vice chairman of the National Solid Management Commission of the Philippines.

For Lao, the issue with plastic is waste management, how plastic is handled at the end of its life. For him, it’s a problem that could easily be solved by recycling,

“We have to admit, nakakalat kasi — ang mga straw, plastic cups, nakakalat. ‘Yon ‘yong nagiging problem (We have to admit, they’re thrown everywhere — straws, plastic cups, they’re littered. That’s the problem),” he says.

These problematic plastic products could’ve been diverted from the environment and away from landfills had they been collected and recycled. But because they’re they’re thrown mindlessly away, they become too contaminated and “it doesn’t make economic sense to recycle anymore.”

of household waste is plastic. —MMDA, 2021

of non-household wastes is plastic. —MMDA, 2021

Multiple studies have pegged plastic recycling rates at a mere 9% of total plastic ever produced with effective recycling at a lower 4%, but Lao remains unperturbed. He has his hopes pinned on recycling as a solution because he claims “the recycling rate for plastic in the Philippines is about 28%.” He cites official DENR data, which in turn references a World Bank study done sometime in “2019 or 2018 about the opportunities lost in plastic as a material.”

According to the World Bank Study, “the Philippines just recycled 28% of key plastic resins in 2019, with 78% value of the key plastic resins lost.”

Lao explains the 28% is “of total plastics combined [because] you have to understand, plastic application is so broad.”

He explains how the different types of recycling — mechanical, alternative, chemical — and how all of them have the capacity to address the different plastic wastes.

Mechanical Recycling. According to Crispian Lao, mechanical recycling is when “we take the product, whether its paper plastic or glass, and turn it again into paper, plastic. or glass, without changing the chemical composition. That is the basic principle. You change the form, restore it back for a functional use. You mechanically change its form.”

Alternative Recycling. Remember those eco-bricks? That’s alternative recycling. According to Lao, alternative recycling is what you do “when it’s not feasible to do mechanical recycling.” You use the plastic waste material, like sachets, candy wrappers, and the like and convert it into construction materials or arts and crafts.

But Von Hernandez warns of the safety of these products made with alternatively recycled plastic waste. “Halo-halong plastic 'yun,” he says. “If you have them tested for leaking chemicals and additives, you might be surprised what you find there.”

Chemical Recycling. Also known as advanced recycling, the 3rd type of recycling intends to “reverse the plastic and convert it back to virgin plastic form” through heat.

According to Circular Economy Asia, “Chemical recycling is any process that turns plastic polymers back into individual monomers (a molecule that can be bonded to other identical molecules to form a polymer).”

It is still not available in the Philippines.

The Philippines has a unique recycling trade, with rigid plastics having the highest recycling rate, Lao says.

He echoes Mang Danny in saying there is value to plastics.

On the day DigiDokyu accompanied the fisherman to Manila Bay, Mang Danny was able to catch a total of six fish and recovered plastic waste — mostly PET bottles — that he was able to trade at P9 per kilo. On that day, his total take home pay was P54, enough money for rice.

If he had remained only a fisherman, he would’ve gone home with just six pieces of fish.

From the looks of it, recycling sounds like a solution to the plastic problem — it provides alternative livelihood for fishermen like Mang Danny, while providing them opportunities to care for Planet Earth, too.

According to Lao, recycling can work even better if we all segregated our garbage at source “whether it’s at the household level or commercial level.”

“Second, is to separately collect it. The frustration of many is that they segregate it at home but somebody comes and collects and puts it in the same garbage truck. That needs to be improved,” Lao said.

But the fisherman from Baseco makes an important distinction: “Kukunin ko lang yung mga bagay na makapakinabang, katulad ng mga plastic na yan, yung mga plastic bottle (I will only retrieve what still has value, like plastic bottles).”

The rest, like discarded sachets and cellophane, are left floating in the waters of Manila Bay.

While those could be used in alternative recycling, a more important concern makes itself known: There is growing number of new products — packaging that looks like paper and cardboard but lined with plastic — that don’t quite fit the current definitions of what’s recyclable, what’s biodegradable, what’s compostable; what’s nabubulok, what’s hindi nabubulok.

“There is a question of definition, how do you qualify something as recyclable,” Lao acknowledges. “But don’t worry, this isn’t just a Philippine problem. This is a global problem. And it’s not just the definition of recyclable. Even the definition of circular economy, sustainability have different interpretations.”

Besides, he counters, “there are now definitions adopted by Philippine National Standards on recycling, recovery for recycling, [what’s] biodegradable.”

“It is already in place, or under discussion,” Lao says, adding he is also part of a technical committee for plastics under the Bureau of Philippine Standards.

“Talagang hindi na mawawala yan dito. Talagang may plastic.” —Mang Danny, fisherman

Interestingly however, he admits “the standards are not yet mandatory in the Philippines.”

“The manufacturing industry of the Philippines, including plastic manufacturing, is comprised of micro- small-, and medium- industries. “Maliliit na companies yan. A lot are small and they would not be able to go through the stringent requirements of conforming to standards,” he admits.

As an assurance, Lao says “we police our own ranks.”

Besides, “while conformance to biodegradable standards is not mandatory, labeling is mandatory under the DTI. Kung ni-label as biodegradable, anyone has the right to report it. And we do. Usually, what we do, we call the attention of the manufacturer and [ask to] show proof. Internal yan. Sumusunod naman, kung hindi sumunod, i-re-report namin,” he said.

Lao shares it was actually the local plastic industry itself that willingly banned products that contained the harmful BPA chemical.

But all that is moot for Von Hernandez, the global coordinator of Break Free from Plastic, a global movement of more than 3,500 organizations, who says recycling won’t solve plastic pollution because “magiging waste din naman yan (it will also become waste).”

“PET bottles are the most recyclable plastic,” Hernandez considers, “but you can only recycle it in a limited number of times before we need to keep adding virgin materials to maintain its quality.”

Says Hernandez, recycling does have a role in solving the plastic problem. “I don’t want to dismiss recycling altogether. There is a role for recycling. But let us not over-inflate the role of recycling. What happens, industries are using recycling to justify continued production. ‘We can keep producing more, kaya naman I-recycle’.”

PHOTOS: Jessica Bartolome

On a February morning, Hernandez began his Zoom interview with GMA News Online by pointing out that “plastic pollution is now recognized as a global crisis to the point that governments around the world are negotiating an international agreement to stop plastic pollution.”

“We are producing more and more plastics and recycling and the infrastructure to handle the materials after their use is totally inadequate. It’s missing in many places,” he says.

According to Hernandez, there is so much plastic waste that even the most developed countries don’t know what to do with them. “That is why we are seeing more and more cases of waste shipments being sent to the global south — SEA, Turkey, Mexico,” where they end up being burned openly, polluting the environments, and creating more pollution.

“Plastics have practically overwhelmed traditional systems,” he says, including recycling infrastructure.

“What we need to do is address the over production. Because if you keep producing more and more, recycling will not be able to keep up.”

According to Lao, there is just so much plastic because there is also so much demand, but Hernandez argues the demand is false.

“It’s supply driven,” he says.

Hernandez has spent the last 30 years in environmental work. He’s seen the rise of the plastic problem since his days as a Greenpeace campaigner against toxic waste and pollution issues. “I’ve seen how the public approaches it and how the governments approach it and how it’s evolved through the years,” he says.

He explains the steep upward curve of plastics demand as the industry wanting to “triple, quadruple plastic production” because “plastics are unfortunately being seen as the saving grace for the fossil fuel industry. That’s their Plan B, that’s why they’re projecting plastics to increase.”

“What we need to do is address the over production. Because if you keep producing more and more, recycling will not be able to keep up.” —Von Hernandez, Break Free From Plastic Global Coordinator

How are plastics and fossil fuel connected? Fossil fuels are burned to produce plastic. While Lao uses terms like “fossil fuel-based plastics” — which perhaps indicates there are non-fossil fuel-based plastics — Hernandez is blunt in saying 99% of all plastics are made from fossil fuels, which is bad news for Planet Earth.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), plastic production in 2019 "generated 1.8 billion metric tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions," with the Organization for Economic and Cooperation Development (OECD) saying plastics account for 3.4% of global total GHG emission.

Meanwhile, a study published in the Nature Journal in 2019 said plastics account for more than double that of aviation sector.

“So it’s not just a waste issue but a climate issue,” Hernandez said.

“Plastics contribute to climate change and not insignificantly because if plastics were a country, they say it would be the 5th largest emitter of the world,” he continued.

While Lao argues “you save a lot of GHG emissions at the transport stage of plastic because it is light” the figures pointed out in these studies are hard to deny.

Burning of fossil fuel, which generates greenhouse gas emissions, is the number one cause of climate change. Experts have repeatedly been saying the world needs to cut its GHG emissions to keep with 1.5C limit of warming set in the Paris Agreement of 2015.

According to a May 2023 report by Pacific Environment, reducing plastic by at least 75% by 2050 and phasing out single-use plastic by 2040 are needed “to align the plastic industry to meet the 1.5C climate target.”

Of course there are various ways to keep with the 1.5C limit. Apart from lowering the emissions there’s also the planting of trees, the lessening food waste, there’s the taking care of things that remove carbon from the atmosphere, like forests and oceans.

But here’s the thing: A 2022 article by Grist say the presence of plastic in the ocean lessens its capacity to sequester carbon.

When carbon dioxide dissolves into the ocean, some algae absorb it and passes it on to organisms that eat it, like zooplanktons. When the zooplankton shits, its carbon-containing poop sinks into the ocean floor, where the carbon is mineralized. This is the natural cycle of life.

Trouble happens when zooplanktons ingest the microplastics floating in the ocean: Because of plastics’ buoyancy, their fecal pellets sink much, much slower than if it hadn’t ingested plastic.

This presents more opportunities for the poop to be intercepted, instead of it sinking straight down to the ocean floor for the carbon to be remineralized.

PHOTO: Jessica Bartolome

Much like floating plastic that could be intercepted by marine life, the possibility of plastic-containing poop being intercepted presents a hosts of problems for the environment and marine life, chief of which is the danger of ingesting it. With microplastics occupying stomach space, zooplanktons — and other marine life — are able to eat less food, resulting in slower species growth.

Onda calls this pseudo-satiation. “Kasi ang kinakain mo ngayon ay plastic, feeling mo busog ka, pero wala ka naman nakukuhang nutrisyon. (You are not eating plastic, so you feel full but you aren’t getting enough nutrition.)”

“Kahit naman tao, 'di ‘ba? Pag tayo gutom na gutom o kaya malnourished na tayo, hindi na tayo makapag-function nang maayos,” he continues.

[When humans are hungry, or are malnourished, we cannot function well.]

As this affects the health, growth, and nutrition of marine life, Onda asks: “Habang dumudumi ang dagat, habang mas maraming organismong naapektuhan, ano yung pagkukunan natin ng pagkain?”

If only recycling was able to do its job of diverting plastic waste away from environments. If only people segregated plastics better.

Hernandez says it’s not the recycling industry’s fault because “plastics have practically overwhelmed traditional systems,” he said.

“There is so much plastics out there, it’s impossible [for recycling] to catch up. You need to address production first.”

While Lao points to “the individual or commercial level that don’t segregate their waste,” resulting in lower recycling rates and a host of problems connected to plastics, Onda takes on a wider lens and says the plastic problem "is a complex issue.”

“Ilang dekada, ilang henerasyon ‘yung tinakbo kaya tayo nakakakita ng gantong problema ngayon. Kailangan ‘yung mga plano natin, ‘yung mga solusyon, dapat malayo din yung pagtingin,” he said.

(The problem has run for decades, for generations. We need a plan, we need solutions that are also far-reaching.)

Onda believes the solution to plastic pollution begins in measuring the problem, because “sa pag-intindi sa kwento ng plastics, nagkukwento din siya sa atin kung paano natin pwedeng matulungan ‘yung gobyerno, ‘yung mga tao na mapababa ‘yung paggamit, mapababa 'yung mismanagement at mapababa din ‘yung plastics na nakikita natin sa environment o sa kalikasan,” Onda said.

[In understanding plastics, we can also begin to understand how we can help the government, and the population to bring down its usage. We can understand how we can decrease mismanagement, as well as plastic pollution in the environment.]

In counting plastic waste in coastlines across the country, PlastiCount is seeing a variety of waste from different locales.

Onda shares how Manila Bay yields the most trash from industry like commercial and food. In Palawan meanwhile, it’s fishing-related garbage.

"Sinasabi kasi sa atin ito na, baka ‘yung approach natin sa Manila, hindi mag-a-apply sa Palawan. So, yun talaga yung goal natin. We are trying to help in crafting policies from the national to the local level."

Meanwhile, Hernandez is certain the plastic problem requires a systems change.

”The main intervention is to reduce and then institute systems that do not require us to be more dependent on plastics production,” Hernandez said, because “plastics mean more climate emission.”

A 2023 study by Plymouth University commissioned by Break Free from Plastic put forward reuse as a solution to the problem of plastic. And while Lao agrees reuse can be a solution, he asks a valid question: “Can you do reusable for everything?”

“You reuse whatever you can, and go rigid whenever you can,” he suggests. “Hindi lahat, masu-substitute ang plastic. Studies have shown that yes, there can be a reduced consumption where a viable alternative exists.”

Interestingly however, the study says reuse should be thought of not as a material — i.e. reusable bags — but as a system.

Says the study: “Reuse should be considered as a system in which reusability is a deliberate objective and in which the packaging item is used multiple times for its originally intended purpose. Within a reuse system, all packaging is owned and managed by the reuse system provider, not the consumer.”

Acknowledging the different needs of each sector, the study argues reuse cannot have a one-size fits all approach.

“The transition to reuse systems should reflect the differing needs of diverse sectors through sector specific systems,” it added. Concerts will require a different approach from e-commerce, food halls from home care, and so it goes.

According to Hernandez, “If we do this correctly, it can address 40% of the problem which is mainly attributed to packaging.”

While Lao says “there is a limitation to what we can shift away from plastic packaging,” for Hernandez, a reuse system doesn’t even remove plastic 100% off the table.

“We are material agnostic because of course, it will depend on the application,” Hernandez says. “It can even be made with plastic so long as you can ensure that plastics, when they are collected and after they have been used so many times, are safely and mechanically recycled,” he continues.

The study recognizes all materials have an impact in the environment, which is why it is putting forward a sustainability breakeven point, which is “the number of uses that a reusable item must undergo before its ‘impact per use’ is less than the equivalent single-use item.”

Besides, “it’s not really about the material,” Hernandez said. “It’s about the system. What system would be better.”

And then there is refill, another possible solution to the plastic problem where an individual brings and uses his own container, doing away with packaging all together, and thereby avoiding pollution.

“There is a question of definition, how do you qualify something as recyclable. But don’t worry, this isn’t just a Philippine problem. This is a global problem." —Crispian Lao, Founding President, Philippines Alliance for Recycling and Materials Sustainability

In 2022, Greenpeace Philippines piloted the Kuha sa Tingi refilling initiative, first in San Juan where 10 sari-sari stores participated in an initial five-month run, successfully avoiding an estimated 8,453 single-use sachets.

Quezon City followed in July 2023 with 30 sari-sari stores. In its initial eight-week run, it was was able to divert 47,601 sachets or a total of 1,428,030 ml of plastics in volume.

QC Mayor Joy Belmonte has expanded the program to 1000 stores, which Greenpeace projects will help avoid the disposal of more than 530,000 sachets.

“Should each store refill once a month, the Quezon City stores would collectively avoid 1,066,666 pieces of sachet waste per month,” Greenpeace said in its Kuha sa Tingi (KST) report, released in March 2024.

“That’s still tiny by QC standards but if you start measuring its impact in terms of saving and avoided cost of disposal and environmental damage, it will add up in favor of the alternative,” Hernandez said.

Pasig City just started its refill pilot with 20 stores, while the rest of Metro Manila LGUs, through the Metro Manila Mayors Spouses Foundation, will soon follow. The foundation has committed one sari-sari store per LGU, and according to Greenpeace, it will match the number of stores committed to further the proposed solution of plastic pollution in the country.

PHOTOS: Jessica Bartolome

In its KST report, Greenpeace pointed to a 2019 World Economic Forum report that said "shifting 40-70% of plastic packaging to reuse systems can potentially eliminate all ocean plastic waste and cut down landfill plastic waste by 50-85%.”

Says Hernandez, such solutions address the root cause of the problem. “Plastic pollution is really the crisis of this linear society — take, make, and waste is the linear society, ‘di 'ba?”

Hernandez says we need to move away from the single-use mentality if we are to solve the plastic problem.

Meanwhile, Onda believes measuring the problem will allow for data-driven solutions that will come from all sectors of society — government, science, businesses, individuals — instead of band-aid solutions, like the swift banning of single-use plastics, that don’t really address the problem.

“Maganda sana siyang idea, pero kailangan natin tanggapin na may isang parte ng lipunan na nakadepende duon sa single-use. Kasi ‘yun ‘yung kaya nilang bilihin,” he said.

[It’s a good idea, but we need to accept that there are members of our society dependent on single-use because that’s what they can afford.]

“Kailangan natin isipin na yung mga pinapatupad nating pulisiya, equitable siya. Ano ‘yung mas magiging akma, ano yung mas makakatulong at equitable. ‘Yung just and fair dun sa ibang parte o sa ibang membro ng lipunang Pilipino,” Onda said, saying we don’t need band-aid solutions.

[We need to think go our policies. Are they equitable? What would be most apt, most helpful, and most equitable? We want solutions that are just and fair.]

He shares a hope in how to deal with plastic pollution: “Sana hindi lang dun sa management na part ‘yung solusyon. Sana nandun din sa production.” (I hope solutions don’t just focus on waste management. I hope solutions also address plastic production.)

Meanwhile, the intergovernmental negotiating committee of the UN Environment Assembly is convening in Canada this April for the fourth round of negotiations for a legally binding global plastics treaty, that aims to address the full life cycle of plastic, including its production, design, and disposal.

The Philippines is among the countries that has been sending a delegation since the negotiations started in 2022. The committee hopes to finally complete a draft by the fifth and final round of negations by the end of 2024.

Amid all these, Hernandez looks to back to Planet Earth as inspiration for solution to this gargantuan problem. “We want to move away from [this linear society] and be more circular, following the patterns of nature,” he said.

Nature makes no waste, he reminds.

This work was produced with support from the International Media Support in partnership with UNESCO.

In-depth special reports and features showcasing the best multimedia storytelling from GMA Integrated News.