By Jaileen F. Jimeno

As a child, Junice Demeterio-Melgar loathed the barking of dogs at night, for it meant unpleasant events were about to unfold. Her mother, Dr. Josefa Demeterio, was a private doctor and the late-night rousings in the 1960s meant medical emergencies; the household would spend hours waiting and worrying until she was home safe.

But Dr. Josefa’s patients in Batan, Aklan, didn’t always have cash.

“Sometimes she was paid in eggs and chicken,” recalls Junice, now a doctor herself.

That early, Junice says, she decided not to follow her path.

“I didn’t view her life in the clinic as a happy one,” she recalls.

But there was her pride for her mother’s passion, too: “She either walked, rode motorcycles, or boats to get to her patients, to serve.”

Junice idolized her father Jose, who was a chemist at the Philippine Sugar Institute. From him, she learned to be adventurous. He taught her sports. He took her on amazing road trips that went on and on, even long after the roads have ended.

Her father tried to shield her from student activism, and she swore off medicine. But things were not to be; her life became steeped in both.

Junice’s father yanked her out of the University of the Philippines Rural High School in Los Baños, Laguna when she was a freshman. It was 1970; student activism was growing rapidly. She was transferred to Silliman University, a long bus ride away from Aklan. It was a gross miscalculation on her father’s part, though: student activism was also strong in the university town of Dumaguete City. Junice joined fellow teenagers in sneaking out of their dorm at night to listen to discussion groups.

When it was time for college, she decided on psychology and sociology. Her Manila-based sister filled up her form for the UP College Admission Test (UPCAT).

“When I saw the acceptance letter, it said ‘Congratulations, you have been admitted to UP’s Pre-Medicine course,” recalls Junice, laughing. “My sister reasoned that it’s easy to opt out if I disliked medicine, but it would be impossible to be taken in if, later, I decided I want to be a doctor.”

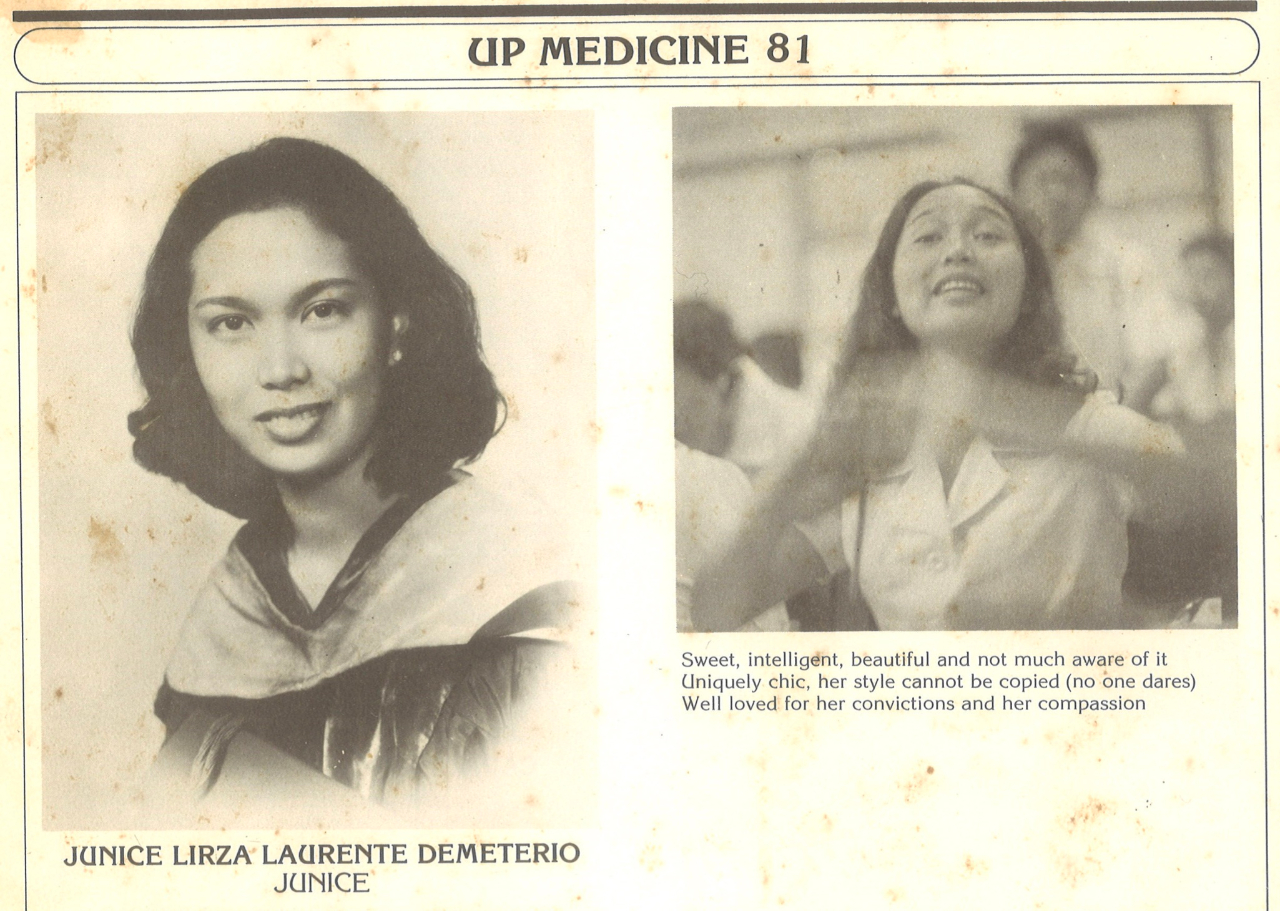

The UP College of Medicine was miserly in admissions. There were only a hundred slots equally divided between men and women. Junice’s sister was right: she came to like medicine because she saw it as a tool to serve the poor. In med school, she no longer resented the idea of being woken up late at night for medical emergencies. She saw it as an adventure, as a way to serve.

Serving the poor

Junice became a doctor in 1981, joining a generation of graduates steeped in activism and bent on being useful in the barrios, like those who mentored them in and out of school. The reluctant doctor and activist has now spent almost all her life serving in the country’s poorest communities.

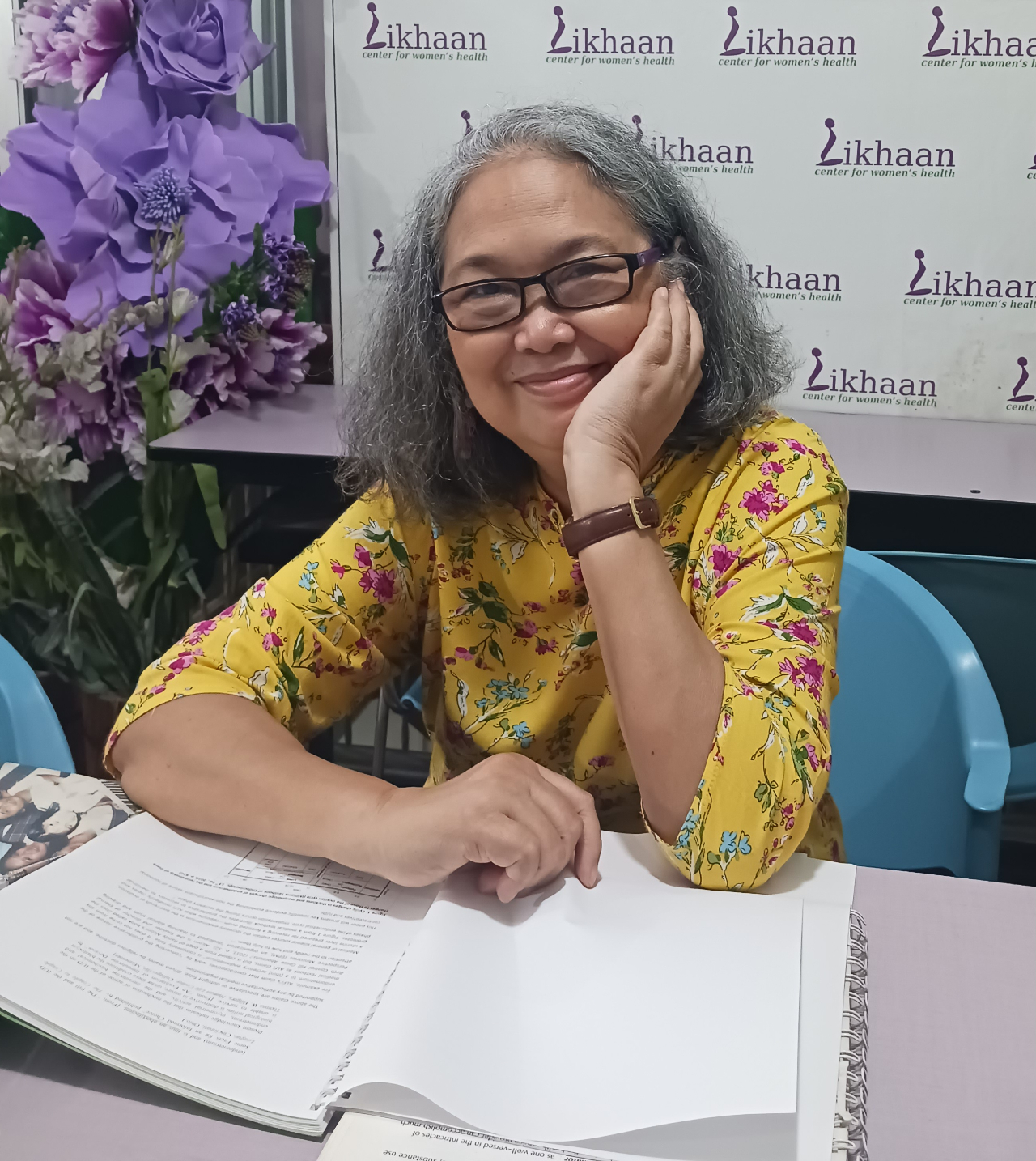

In 1995, after teaching and working in non-government organizations, Junice co-founded, led, and managed Likhaan Center for Women’s Health (Likhaan) and never left. She oversaw the organization from infancy, growing it from two to 10 clinics. Last year alone, Likhaan served over 46,000 women and men for their reproductive health needs and continues to do so despite funding problems, religious rigidity, and narrow-mindedness.

“It took me a long time to understand religious hardliners, those who have a very narrow-minded view of sexuality,” she says. “But I have learned to accept it and to not lose my focus.”

Sandwiched between the malls of Divisoria, the oily, diesel-perfumed streets of Port Area, and market stalls selling fruits and meat that may or may not have been smuggled from China, a Likhaan clinic stirs to life at six in the morning. It is a two-story apartment building with windows that open to spaghetti-ed cables for power and phones, like so many streets in Tondo. A neighbor beats a door mat against a railing, showering dust and dirt on almost a dozen women who have lined up to be seen early.

Among them is Malou, who is up for a birth control implant, her third. The device is good for three years and the 29-year-old swears by it. She was not even 20 when she first got pregnant. She wore an implant after giving birth and then shifted to pills.

“Nakalimutan ang pills, nagkaroon ng pangalawa (I skipped some pills and got pregnant with the second one),” says Malou, laughing.

She has since stuck to implants. Her firstborn is now nine years old, her second, four. She has been a Likhaan patient since her firstborn. While Malou can get checked and get implants in the public hospital where she gave birth, she and her fellow patients in the waiting line choose Likhaan.

“Mahaba na ang pila, susungitan ka pa (The line is long, and the staff can be unpleasant),” says Malou. “Dito, mababait sila at ipapaliwanag mabuti ang lahat sa iyo (Here, they are nice and explain everything well).” The other women in line chime in to agree.

Children are expensive, Malou says, and her husband’s income as a truck driver is barely enough to cover the cost of shelter and food. Another child and schooling expenses will make it impossible, so she gets the contraceptive implant, ignores the pain on her inner arm, and proceeds to buy items from Divisoria that she can sell from home.

An implant costs P3,000, but is free for those who cannot pay. Those who have PhilHealth can use their cards. Likhaan’s other resources are given free; the clinics also provide prenatal and postnatal care.

Maternal death

In the Philippines, up to seven women die daily due to childbirth, according to the 2021 data from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

Ironically, Junice herself almost became part of this statistic. She spent three days of her life in a coma, bleeding, after giving birth to her son.

It was 1989; she had decided to give birth at home. It was an option forced on her and her husband, a former student activist who had already been arrested twice. On standby was her doctor-mother.

“I did not have prenatal checkups,” says Junice. “I only sent letters to an obstetrician-gynecologist friend and gave her updates on my weight gain.”

After a 12-hour labor, with her baby’s head already elongated due to prolonged delivery, Junice bled heavily and lost consciousness. All she remembers of those three days were how comforting the sleep of the nearly dead was.

She was brought to the East Avenue Medical Center where, fortunately, a former schoolmate was on duty at the emergency ward. Junice was rushed to the operating table and in days received 11 bags of blood.

“When people say women die in childbirth, I know that,” says Junice. “My life didn’t flash before my eyes. I didn’t even know I had given birth, that I had a son. My husband went everywhere to find blood for me. It was a desperate situation.”

Lifeline

These days, the doctor oversees clinics for women in destitute locations, in desperate situations. Likhaan has clinics in Manila, Navotas, Pasay, Quezon City, Bulacan, Cavite, and Eastern Samar. The clinics are open from Tuesday to Saturday, from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Their patients are so poor that Likhaan sometimes sends a vehicle to fetch those due for a checkup. They are given money for fare for the trip home.

Perhaps the secret to Likhaan’s longevity is its creativity in solving problems like this. In the early 2000s, the organization dressed up a van, painted it pink, and deployed it to areas where its patients lived. Likhaan named it “Tarajing,” loaded it with medical staff and stuff, drove it to barangays, and held consultations and checkups inside it.

One Likhaan worker shares that this grassroots accessibility is a lifeline for women with abusive partners. This allows them to access contraceptives and counseling.

“May mga lalaki kasi na ayaw pa rin ng family planning (Some men do not like family planning methods,” says the worker. “Blessing daw ang bata (They say children are a blessing).”

Funding Likhaan

The concept of delivering service to the poorest of the poor may sound quixotic and romantic even, but the economics of it is not. To fund Likhaan, its managers and board members continuously look for agencies that will support its programs and its people. It has 74 staff with a funding requirement of P40 million a year.

“That’s why I am glad we have PhilHealth now,” says Junice.

She explains that PhilHealth reimburses Likhaan for some of the implants it provides, saving portions of the organization’s funds for other services.

Junice and her team also work with government in pushing for policies that will improve maternal health and gender equality.

Likhaan has received support from the government of Canada, the Netherlands, the European Union, the United Nations Population Fund, the Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund, Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), and the Canadian NGO Inter Pares. It has partnered with some local government units and local business groups in carrying out campaigns and projects.

But the funding support is far from providing Likhaan’s staff with a luxurious lifestyle. As executive director, Junice receives P40,000 a month. Not a hefty amount as chief of the team. Their janitor receives P15,000 a month.

“I have learned to live simply, walang amenities,” says the doctor. “I am used to simple living and hard struggle.”

The pay is low, yet Likhaan’s team members use their salaries to help out. Says Junice: “We also donate to our organization. My colleagues donate, too.”

This became crucial during the pandemic when the lockdown confined their patients to their barangays. Likhaan became the nearest birthing clinic for some women.

Likhaan clinics are helmed by midwives and nurses; it cannot afford a doctor. They have tried in the past, with the latest at a fee of P72,000 a month. It did not pan out.

“Walang gustong mag-stay sa community (No doctor wants to stay in the community),” Junice says. “Wala pang isang buwan, hindi na kaya (They don’t last a month).”

One doctor who organizes medical-dental missions laments that volunteerism in the medical sector has deteriorated over the years. Doctors and dentists not only demand payment for their services during missions, they are unwilling to stay until all patients are served. Worse, they ask to take home donated medicines to sell to their patients.

“Wala nang gustong mag-volunteer (No one wants to volunteer),” the doctor says.

To be sure, Junice grew up in a different era, when many doctors responded to calls to serve in the barrios. Among them were the late Juan Flavier in 1960, who served in Nueva Ecija and Cavite, and Jaime Galvez Tan, who served in Leyte and Samar. Both later served as health secretary of the country. Flavier was elected senator for two terms, 1995-2001 and 2001-2007. He died on October 30, 2014 at the age of 79.

Whenever he visited Manila, Dr. Galvez Tan spent his off days speaking to UP College of Medicine students. One of those who listened to his talk about serving in the countryside instead of working in a hospital was a student named Junice Demeterio.

“I always remember Junice as one of those who was most active in her class,” Galvez Tan says. “Her batch had one of the biggest number of graduates that went to the communities and in various ways, found how they could serve God, our country, and the poorest of the poor.”

Junice remembers Galvez Tan as their guru, wearing a white coat and stethoscope while mobilizing medical students to serve in flooded areas during typhoons.

Mentor and mentee stayed in touch over the years. Dr. Galvez Tan is a trustee of Likhaan.

“Junice is exceptional because she fights for the rights of the poor in an open space,” Galvez Tan says. “She brings it to the public. She formed an organization which is unique and up to now, not paralleled by any organization in the Philippines.”

He says that her work is now recognized globally as proven by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s visit to Likhaan’s Tondo clinic in 2017. Diplomats from European and other countries also make Likhaan clinics one of their stops.

Junice credits Likhaan’s prudent and honest use of funders’ money for the good relationship it has with its donors. Its financial statements are uploaded on its website.

But Likhaan needs more funds. It has campaigns centered on AIDS awareness, violence against women, and reproductive health among the young. Its clinics respond to rape victims, women needing post abortion care, and cervical cancer screening. Maintaining its clinics is Likhaan’s most expensive program.

These days, Junice is working on finding a more solid and sustainable funding stream for Likhaan. She has also begun to train the organization’s next leaders.

“I am grooming our second liners,” she says. “I hope I can retire soon; after all, I am 66 years old.”

That is a lifetime of being a community doctor for someone who had resented the barking of dogs because it meant a medical emergency and a sleepless night.

In-depth special reports and features showcasing the best multimedia storytelling from GMA Integrated News.