We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

By SUNDY LOCUS and ABBY ESPIRITU

December 30, 2022

Ara had always been fascinated by the high-end life. Walking into the fanciest clubs in her pricey heels, with a pricier bag in hand.

It felt like a faraway dream for Ara, who had grown up steeped in the hustle culture. An honest day’s pay for an honest day’s work. Climb her way to the top. For her, that was how life was supposed to happen.

Things changed during sophomore year in college.

“In my freshman year, I was the only one in college so I was the only one who needed money for tuition. When I started my second year, a sibling started college too. My allowance got smaller. I needed to find a way to pay for half my tuition, plus daily expenses,” Ara said.

That was when she met her first sugar daddy in 2016. Though she wasn’t naive, she leaned on what turned out to be a bustling community of sugar babies to figure out how to do things: communicating with her clients, attending to their needs, negotiating her terms, ensuring her safety, and doing her job.

While other young women leaned on sugar daddy dating sites, Ara had most of her clients referred to her by a close friend living in Japan. “Mom,” as she called her, introduced her to several sugar daddies — foreigners, company executives, and wealthy businessmen.

“Her rich friends are in Japan — Chinese, Singaporeans, who are looking for sugar babies,” Ara said.

“Mom” would figure out how much the clients were willing to pay, what they expected from their sugar babies, and even their weird fetishes. “I was lucky to have her,” Ara said.

She had always felt the least seen and least pampered in her family, so sugar dating changed Ara’s world. While her parents could only afford to buy her one pair of shoes every year, her sugar daddy could take her on a shopping spree “at a snap of a finger.”

“At that time, I was overjoyed. I was overwhelmed. Of course, I didn’t have to think about mony because every month something would come,” Ara said.

Dating Ara came with a price tag. Her services cost an average of P10,000 to P20,000 per week — nearly twice the monthly minimum wage for workers in Metro Manila — but the overall rates still depended on a written agreement she signed with a prospect. The highest payment she received was P60,000 per month. This was apart from allowances she spent mostly on shopping. There were also gifts lavished upon her in the form of luxury clothes, bags, trips, and mobile phones.

“It got to a point where a client would give me TV sets, a refrigerator, home appliances. I didn’t know how to explain it to my parents. I told them I won a raffle at our Christmas party, even though I didn’t work at a company,” she said.

With the money came the lifestyle she grew to love. She made enough that she would even regularly treat her friends at school to buffet dinners and hotel parties. Some would wonder how she could afford her glamorous lifestyle, but Ara never admitted to being a sugar baby.

“It’s still embarrassing because it’s still sex work. You do sex work, at the same time it’s still not legal here,” Ara said.

But while she won’t open up about it to friends, she is defiant about her right to go into the trade. “It’s my body, my choice. I’m good at it so why not monetize it?”

While sex is part of the sugar baby game, Ara is quick to note that it’s not the only part of the trade. One of her previous clients confessed to being lonely despite his success. Through her community with other sugar babies, she figured out that it was her job to help ease away her sugar daddy’s melancholy — cooking meals, giving massages, and just listening to their problems.

Still, sex remains a big part of the agreement.

“The worst I’ve done is a ‘golden shower.’ It’s kinda gross: he’d pee on me. He just can’t do it on my face, just on my body,” she said.

Of course, it all comes with strings attached. Allowing a golden shower, Ara is quick to add, “that’s a higher rate.”

Sociologist Michael Pastor said sugar daddy dating has long been a phenomenon in the country yet it remains to be an “under-explored” social issue.

“Most of the time people would just treat the situation in stride. They would look at it as if it doesn’t happen, or as if it were just for fun. Sometimes popularized in pop culture, stereotypes and all of that. But the sugar daddy phenomenon exists,” he said.

According to Pastor, sugar dating happens “on multiple levels or within a spectrum.” And while money may be the main driving force behind sugar dating, there are psychological and cultural facets too.

“One of the persons I talked to, who had a relationship with a Filipina, would say that some foreigners would prefer having a Filipina partner because they know how to care,” the sociologist said. “It’s something they see in the cultural values of Filipinos. We care a lot for our families.”

But Pastor noted that these supposed “admirable traits” are also present in women engaged in various sex work channels, like “guest relations officers” that work in clubs and beerhouses.

The nature of sex work has been a long-standing discussion in the Philippines. Under Article 202 of the Revised Penal Code, the industry is deemed illegal, and “women who, for money or profit, habitually indulge in sexual intercourse or lascivious conduct” are considered prostitutes.

Curiously, under Philippine law, prostitution is a crime only women can commit.

Those who fall victim to human trafficking, however, may be given social protection under Republic Act 9208 or the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act (ATIP).

But is sugar dating sex work? Dr. Sharmila Parmanand, a gender diversity expert, said the answer is not quite so simple.

“I think broadly, yes. In some cases there’s a provision of sexual services, but the term ‘sex work’ is a personal term. I think the important thing is to ask the person if they identify as a sex worker,” she said. “But technically, the definition of sex work is ‘Engaging in a range of sexual services as income generation.’ But I don’t want to label them unless they label themselves.”

Women’s group Gabriela takes a different stance, however, as it described sugar dating as a “glamorous” form of prostitution.

“Why are we saying it’s glamorous? Because this is different from the form of prostitution in dens, casas, and beerhouses. This happens online,” said Gabriela Deputy Secretary General for Visayas KJ Catequista.

Still, she believes that despite the luxurious lifestyles flaunted by those in the industry, sugar dating “is another form of commodification” of women. “Some enter the industry for luxury but they are only a small percentage. Most of the people engaged in sex work turn to it because of the lack of employment opportunities and because of poverty,” Catequista said.

The unequal power relationship between the sugar daddy and the sugar baby, she said, is largely influenced by his quality of life and her vulnerability. “We can say for a woman who doesn’t have work, this can be a source of finances. They really have that right, but if we ask, is sex work empowering? There’s nothing empowering with unequal power relations,” she said.

Parmanand, who has done substantial work studying sex workers in the Philippines, says the subject deserves a more nuanced view, which includes listening to the stories of the sex workers themselves.

“We and they understand why sex work is not OK. But as long as we cannot offer a better alternative, maybe it would be better not to ban it. That’s where they are coming from,” she said.

While sugar dating existed before the pandemic, it made noise in 2020 after Malaysia-based Sugar Book released data that its membership in the Philippines grew to 80,000 amid the COVID-19 outbreak.

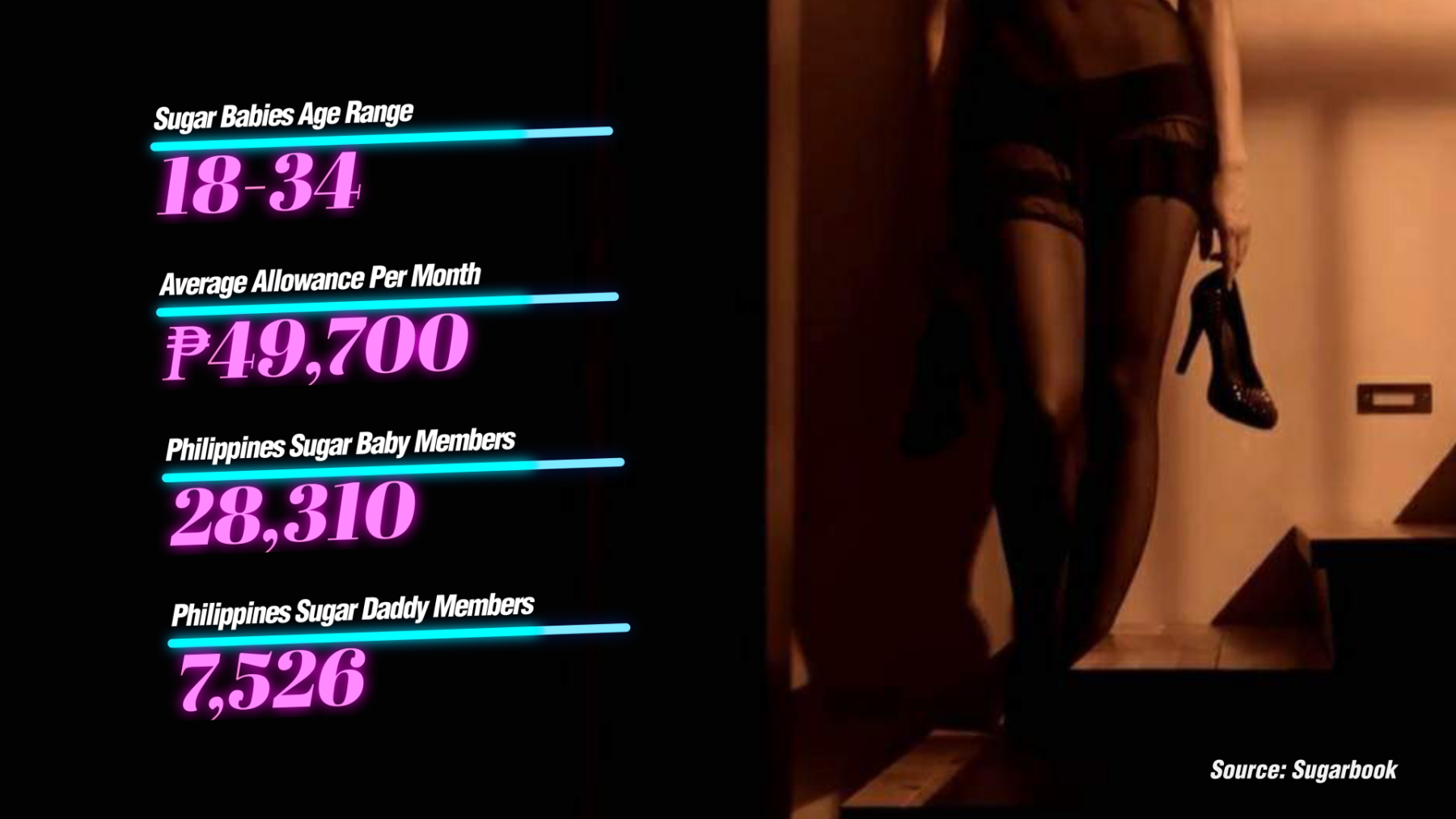

A year later, the “luxury dating” site reported that the Philippines is among the top three countries with the highest numbers of users in 2021 — with more sugar babies than sugar daddies or mommies registered. The app listed at least 126,985 sugar babies in the country and 33,156 sugar daddies or mommies. Most sugar babies on their site are students aged 18 to 34 years old who receive an average monthly allowance of P49,700.

It was this same opportunity that drew Amber into the sugar dating pool.

Her family was among the thousands hard-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic that saw her finances dwindle and her goal of finishing a college degree in limbo.

It wasn’t quite a desperate situation, but when a friend explained the perks of sugar dating, she decided to give it a try.

“I tried to look for something that was quick cash. Minimal effort but quick cash,” she said.

The man who was referred to her became her first client. They only dated for weeks but it lasted long enough for her to learn how to land another sugar daddy.

Most of her clients were from sugar daddy dating sites but unlike the “typical” setup where a client steadily provides for a sugar baby in a staggering time, Amber said her relationships usually only run for weeks, with her longest one lasting for only one to two months.

“I had a lot of sugar daddies. They just disappear. I don’t know why but ‘ghosting’ also happens in sugaring,” she said.

After slowly learning the ins and outs of the trade, Amber knew she had to be smarter about it. She began entertaining two to three sugar daddies at a time to make sure she would never be behind her bills in case a client decided to “ghost” her again.

Her rates ranged from P10,000 to P12,000 per week depending on the consensus between her and her sugar daddy. Some gave her P15,000 to P18,000 per month, others P12,000 to P15,000 every two months, while several clients liked the so-called PPM or “pay per meet” set up where they hand her allowances after each meeting.

Amber understood that she had to be wise in earning but wiser in handling her finances. She divided her money into tuition, family expenses, and self-investment while the rest went to her savings.

“I told myself long ago that I should not spend my money just because I have it. I should not be a one-day millionaire. So I made sure that I know my priorities when the money comes,” she said.

Two years after starting out as a sugar baby, she graduated from college.

And while money may have been at the center of her relationships, she took note of other lessons along the way.

“It’s not just about the money involved but it’s more of the experience and knowledge that I can gain from these kinds of people. Sugar daddies are real,” she said. “Aside from having money, they’re educated, they’re businessmen who talk to a lot of people. They’re willing to share if the sugar baby is willing to learn.”

With romance comes finance, some would say, but Amber said the trade also has its dark side.

“It’s a lavish experience if you caught the so-called biggest fish in the sea. If you are with someone who is very rich and will take care of you. But in my experience, it is not. It is a case-to-case basis,” she said.

The lifestyle only looks lavish because some sugar babies are too quick to flaunt their newest iPhones and designer handbags on social media.

And while most sugar daddies are simply looking for companionship, there are those who look for young women they could control.

But the worst she experienced was being called names and being blackmailed by a previous client.

“Truth be told, I had an experience wherein I sent pictures without a timer and it was used against me. I got blackmailed but luckily, it didn’t reach my family or anyone I know,” she said.

Between pangs of fear about the experience that lies ahead with her clients, Amber said women like her are sometimes left without a choice.

“It’s clutching at the knife’s edge. We’d sell ourselves without knowing if the client is serious about us. Because if you’re a person who’s really in need, you’ll bite the bullet. You’ll give in to their demands uncertain what you will get in return,” she said.

These days, Amber is active in an anonymous forum website where she gives pieces of advice and shares her insights with those interested in becoming sugar babies.

She is also looking for other employment opportunities, with her college degree serving as a weapon in charting her new future.

“My realizations in being in the lifestyle for a year or two is that — it’s a glamorous lifestyle if you look at it from the outside but once you’re inside, the anxiety will eat at you,” she said.

The “growing trend” in sugar daddy dating in the Philippines amid the pandemic prompted then Senator Leila de Lima to file a resolution seeking a legislative inquiry on the alternative source of income in 2021. De Lima said there was a “need to examine the underlying conditions in our population that render them [young women] vulnerable to exploitation by these kinds of websites that prey on women, even minors, who are in desperate need of financial assistance.”

She also said the alleged cases of abuse and exploitation under the dating scene should be investigated to gather more concrete data on the industry to further protect women’s and children’s rights amid the pandemic.

According to Dr. Joan Mae Perez-Rifareal, who specializes in adult psychiatry, there are plenty of reasons why women may go into sugar dating. "They think they cannot trust anyone, or that everything should be based on give-and-take. They have to give something to earn what they want from other people," she said.

"Others do it due to peer pressure or to conform, especially when they see that it became the basis for likes and comments on social media — when someone is rich. There are many reasons for it and may manifest simultaneously."

But during a pandemic, monetary benefits often entice sugar babies into agreeing to a transactional relationship. Citing Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Rifareal said some people find themselves in a “survival mode” that forces them to turn to sugar daddies as a way out.

“When someone is in survival mode, she needs to address her necessities. When before, she was buying things out of want, now it’s different because the situation has transitioned into survival mode, especially during the pandemic,” Rifareal said.

For Catequista, the Gabriela official, the government should shut down sugar daddy dating sites operating in the Philippines, with its business owners and their rich clientele penalized for actions that violate the Anti-Trafficking in Persons (ATIP) Act.

“All sites that encourage violence or that perpetuate prostitution among women,” she said.

Parmanand, however, said there needs to be a distinction between those who are victims of trafficking and exploitation, and those who had chosen to do sex work.

“Those who do not want to do sex work, they need to be rescued, that is important. But those who do not want to be rescued should not be rescued. That’s where they’re coming from. They’re saying, ‘We want to be heard instead,’” she said.

“All our laws about sex work, they never consulted sex workers. They would consult victims of trafficking, victims of sexual exploitation. That’s important, but it’s not enough.”

Ara is now 24 years old. She stopped sugaring in 2019, after a series of traumatic encounters with sugar daddies who were controlling and even dangerous.

“For about six months, I had a driver, I had a car, I had a condo unit but all of those were under his control. He knew where I’d go, and who I was with. It’s lavish but worrying.”

An encounter with a different client, meanwhile, almost turned to violence. He had come home drunk from a bar and was carrying a knife.

“When I came out of the bathroom, he was holding the knife. I had no idea what he was going to do, but I had a rush of adrenaline. I went straight out. Thank God I had left the door unlocked. I forgot my heels, I only had my bag. I went out of the hotel without shoes on,” she said.

Ara lied low following the incident, but the pandemic pushed her to go back into sugar daddy dating. It was supposed to be a one-time thing but as the lockdowns went longer than expected, she began losing more and more gigs as a full-time make-up artist, prompting her to spend her emergency funds.

Alarmed by how her savings were slowly draining, she also began selling her sensitive photos and videos online.

As the restrictions eased and the world began functioning under the so-called “new normal”, Ara said she logged off from sugar daddy dating and decided to leave it now for good.

Asked if she will recommend such work to others, Ara said no. There’s too much stigma surrounding sex work because it is illegal in the country. However, similar to the friends she gained in their community, she is open to advising girls who decide to get into it.

It was a rollercoaster ride but Ara remains defiant about her experience.

“Now I can support myself. I can buy everything I want. I have work. I regret nothing at all. I am really happy I did that,” she said, pausing before tweaking her answer.

“The only thing I regret is that I didn’t charge a higher rate.”