Text and Photos by ATOM ARAULLO

August 5, 2022

The Chinese Port in Bongao, Tawi-Tawi buzzed with a singular energy, at once familiar and exotic, on an overcast Sunday morning. Along the pier, massive wooden passenger ferries nodded silently over the water. People scuttled along narrow streets next to tricycles and heavily tinted vehicles, their movements carefully synchronized, bodies and machines moving here and there in steady inefficiency. Three stories above the bustle, colorful laundry fluttered on a roof deck, briefly animated by a soft breeze. Farther away, the vertiginous Bud Bongao peak dominated the skyline, a limestone monolith jutting out like a jagged tooth over the landscape.

Blue backpack slung over her shoulder, Cansida Arances navigated the port expertly, slipping between men carrying baggage, sacks of rice, and plastic jerrycans filled with fuel. Arances was making her way back to her hometown of Barangay Buan in Panglima Sugala, where she also works as a volunteer teacher. Teacher Sidang, as she is called by her students, had high cheekbones, even, brown complexion and wide-set eyes behind a pair of rectangular glasses. Dressed for comfort, she wore a light blue hijab, a checkered long-sleeved shirt, jeans, and off-white trainers. She climbed a narrow gangplank to board the ferry, pushed past a gaggle of men, and ducked under a low ceiling to enter the lower deck, which was already filling up with passengers.

These boats, or lantsas, are a backbone of transportation in Tawi-Tawi, moving people around the different islands of the province. They are also an anachronism, a holdout from the rest of the country where wooden ferries have mostly been phased out.

Inside, seats were limited. Early birds spread blankets on the floor and stretched out beside their belongings. A young mother secured a hook on a low beam and fashioned a cradle out of a malong, a length of colorful fabric ubiquitous in this region. An enterprising man knocked together a small bed out of two sacks of rice and curled into position. Hammocks draped from the rafters. A pair of hens cowered in a corner while travelers squeezed between baskets of vegetables and crates of eggs and soft drinks lining the passageways. Up a steep stairway, the cramped upper deck, barely high enough to sit in, was also packed with people and possessions. A tiny, dimly-lit bridge with squinting windows crowned this claustrophobic wonderworld. The captain’s infant son was propped on the console in front of him, like a life-sized ornament.

Teacher Sidang settled on a bench and rested her head against a panel. She was a picture of calm and patience. Sidang made this trip regularly over the weekend to visit her two eldest daughters who live in Bongao.

When I asked her what time the boat would leave, as we were now an hour behind the announced schedule, she gave me a knowing smile. “When it’s ready,” she said.

Now it was time to go. The massive diesel engine roared to life, engulfing the ship in a cocoon of noise and vibration. The hulking boat slid over emerald waters, which was unwrinkled on this gray, windless morning. Salty air wafted through the deck, providing some relief from the stifling humidity. A youngster sitting on a pile of bags smoked his second cigarette. He didn’t lift his eyes from his cellphone, which he held sideways with two thumbs over the screen, intently focused on a game. The baby in the makeshift cradle, gently bobbing, was blissfully asleep. Distant hills and verdant coastlines cast dark reflections over the flat water, a slow procession of green on green. There was something prehistoric, even primeval about the seascape, like it poured out from an archaeology book.

Tawi-Tawi is frontier land in more ways than one. The farthest province from the seat of power in Manila, the capital of Bongao sits just 50 kilometers away from Malaysia-administered Sabah.

The historical connection between the two territories runs deep, with blood ties spanning both sides of the border.

Tawi-Tawi was once part of the Sultanate of Sulu, a territory predating Spanish colonization that encompassed the Sulu Archipelago, parts of modern-day Mindanao and Palawan, and portions of northeastern Borneo. During its peak, the Sultanate is said to have had the most advanced culture and socio-political system in the entire archipelago.

However, the prosperous maritime power fell into decline in the early 20th century after struggling against successive colonial powers. Since then, development in this part of the Philippines has been slow.

In the past decades, government neglect, social inequality, a porous frontier, and pockets of lawlessness have given rise to separatists and freedom fighters as well as pirates, smugglers, and extremist groups.

Even today, despite years of relative peace, its image as a place of instability has been hard to shake off.

Sidang wants to see change in the place she calls home, and believes she can help achieve it one student at a time.

We arrived in her village four hours later. The island has no electricity, no cellular signal, not even a local police force. Instead, a detachment of the Philippine Marines provides a measure of security.

The village chief received us at the port, wearing a polo shirt and shorts. He was a heavy man with drooping eyelids and a stolid temperament. A few hundred meters away, at the edge of a mangrove forest, a roaring speedboat disappeared behind the curve of the island. The chief glanced in its direction, then back at me, his expression unchanged. He already knew what I was going to ask. “Fuel smugglers from Malaysia,” he said candidly.

It was a short walk to Sidang’s house. Their home stood over the shoreline, held up by dozens of wooden poles buried into the seabed. Weather-beaten planks, laid out side by side without nails or lashing, formed a walkway that flexed and wobbled under our feet. Sidang shared a single, bare room with her mother, three youngest children, and Parker, a gray, phlegmatic tabby cat. He gave the slightest acknowledgment of our presence before walking away, uninterested.

Sidang removed her backpack and exhaled sharply. It had been a long day. At the age of 50, she had many years of teaching experience, but was not yet a licensed teacher. Sidang graduated from the Mindanao State University with a degree in education, and although she had taken the teacher’s certification exam nine times, she had yet to make the grade. “It’s so hard to prepare for it when I have to juggle work and my responsibilities at home,” she said. “I don’t even know if my review books are up to date.”

In the meantime, Sidang has been working for various education-based non-government organizations. She was now employed by BRAC, an international non-profit whose projects in the Philippines center around the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao or BARMM. With a monthly budget of P15,000, Sidang teaches reading and writing to illiterate children: one house at a time. It’s a physically demanding and time consuming job, but one that Sidang has grown to love.

“I just adore the kids.” Sidang said. “I see my own children in all of them, so it breaks my heart to see that many don’t know how read and write,” Sidang said.

Access to education and literacy are longstanding problems in BARMM. A pre-pandemic survey by the Philippine Statistics Authority showed that the region had the lowest basic literacy rate in the country at 83 percent. Meanwhile, a 2015 study revealed that just 4 in 10 students enter elementary school in Tawi-Tawi, with only 2 graduating. The worst educational outcomes were observed in Muslim indigenous communities like the Sama Laut and Badjao, which are the dominant ethnolinguistic groups on the islands. On the average, only 1 in 3 of the seaborne people were literate. They make up the bulk of teacher Sidang’s students.

She was up early the following morning, preparing her teaching material in the milky half-light. Sidang assembled colorful cartolina, modules, picture books, black markers, extra pencils and erasers, and some sweets as pasalubong or gifts for the kids. The inert air of the pre-dawn laziness foreshadowed the effort of another hot day. Sidang rents a small boat to reach the pondohan —mid-sea stilt house communities that dot the region. She now sat balanced in the middle of the skiff, her books and a clear plastic envelope placed neatly on her lap. Soon, the sun peeked behind the dark silhouette of the island, illuminating the tops of the tallest coconut trees. The boat chop-chopped steadily over the water. From a distance, the stilt houses looked like tall, gangly creatures perched above the shimmering sea.

A family of four was already waiting for us as we approached the first house. Sidang clambered up a ladder onto a wide platform and made a beeline for a 5 year-old girl wearing an oversized t-shirt and a striped skirt. The teacher knelt down, giving the girl a hug and a tender kiss on the cheek. “This is Geralyn, my most well-behaved student!” Sidang gushed. She became animated with a sudden burst of energy.

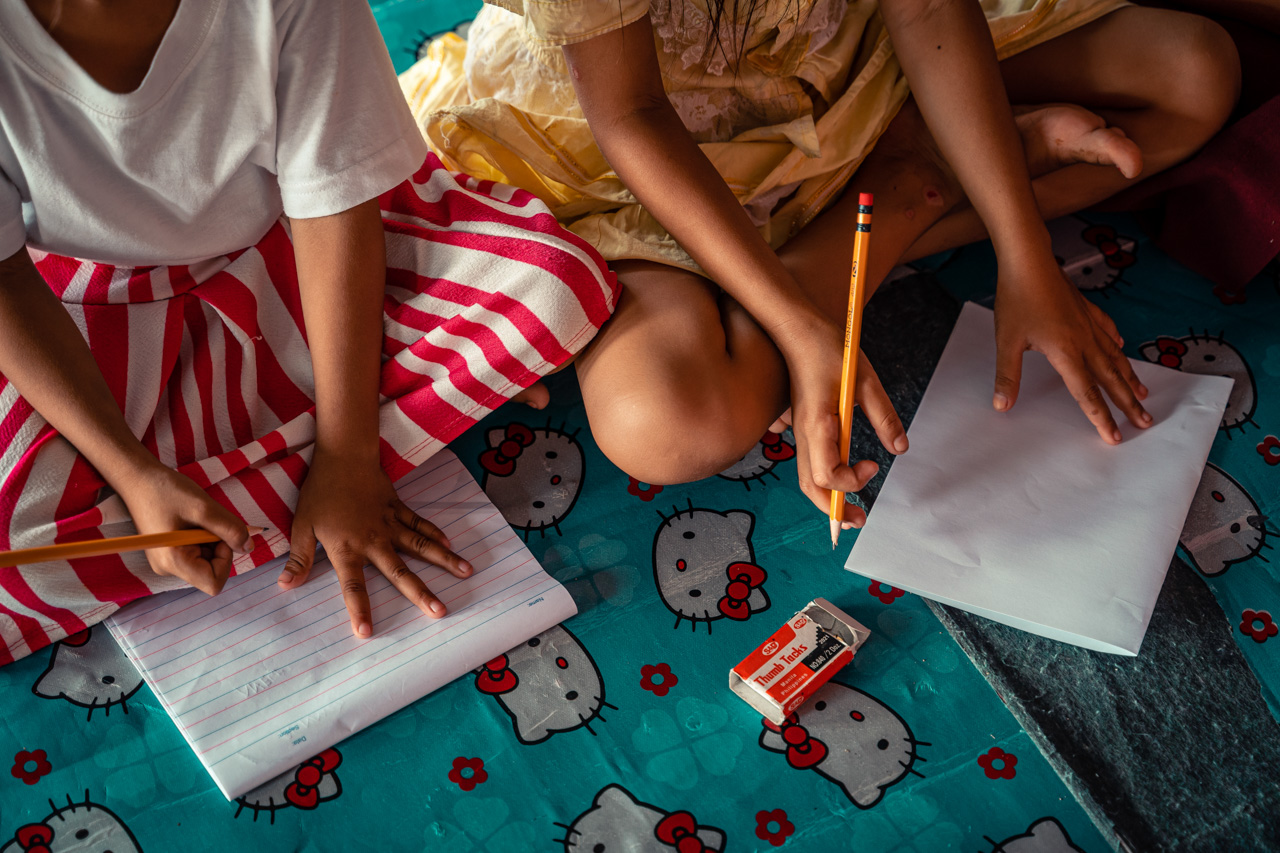

Teacher and student sat down in a shaded common area. It was immaculately clean and well-organized, with pillows, clothes, and blankets neatly folded and stacked at the far end of the room. On a small shelf, plastic shampoo bottles and other toiletries were arranged by height. There was no furniture. A section of linoleum printed with a Hello Kitty design covered the floor. As Sidang taped her visual aids to the wall, two more girls arrived on boats and joined the duo. The kids, sitting in a semicircle and gripping newly-sharpened pencils as long as their forearms, did not take their attention away from Sidang. There was an eagerness in the girls’ eyes as they recited the letters of the alphabet, as if they were unlocking the secrets of the universe with every syllable uttered in rote.

Many of the children in these off-shore communities have never gone to school. Even though there is a public elementary school in the nearby island, where Sidang herself lives, going there was not an option for families who can’t afford the fuel for daily trips on the same boats they used for livelihood. Indeed, most only venture beyond their homes out of absolute necessity, thereby growing accustomed to a life of seclusion. This physical and social isolation has a price, often cited as a major factor in the low level of education in these communities.

To address the problem, Teacher Sidang’s NGO originally made a floating school anchored near the stilt houses, a more accessible place where kids could gather for lessons. It was a smash hit, well-used and beloved by the community. But after a while, the school finally lost its battle with the elements.

“One day, strong winds and waves just took it away,” Sidang said after her lesson. “The people couldn’t do anything, they just watched it drift off into the distance.”

That was four years ago. We hopped on our boat and made our way to another group of homes situated in a thick mangrove forest. Up a small hill on a finger of land, we arrived at another modest house on stilts. A dark-skinned man received us with a broad show of affection. He had friendly eyes and deep lines along both sides of his mouth, like a pair of parentheses. “Go right inside,” he said in Tausug. “She’s been waiting for you.”

Sidang loved all of her young students, but there was a special place in her heart for this one. Marsila was wearing light blue printed pajamas, her long black hair neatly gathered in a ponytail. She had slightly impish features, a wide smile, and an unreserved demeanor.

Sitting in one corner of the house, Marsila and Sidang began their lessons. The young girl recited with confidence and enthusiasm. Sidang brought out her picture book of letter associations and leafed through the pages. A is for apple. B is for ball. C is for cat. “Kuting!” Marsila exclaimed. Their own cat gave birth to four kittens recently, she shared. D is for drum. “Tambol!” Marsila said, pretend playing on a set of invisible drums. E is for elephant. Marsila paused, marveling at the picture.

“What is that?” she asked. “A carabao?”

Sidang laughed. “It’s not a carabao,” she explained. “It’s a very big animal with a long nose.” Marsila stared on in wonder.

Marsila’s father Mansul, the man with kind eyes, earns a living by farming agar-agar, a kind of seaweed used for food, cosmetics, and bioplastic. It is the main livelihood in many impoverished communities in Tawi-Tawi. Rows of seaweed growing just under the sea surface cover hectares of coastline, thriving in places with a gentle current and generous sunlight. Agar-agar is easy to cultivate and grows year round. But even as local and international demand for the raw material continues to rise, small-time farmers here earn a pittance.

Mansul only brings home around 6,000 pesos (114 USD) on a good month, not nearly enough for the needs of his family. They scrape by. Options were limited for the man who only finished two years of basic education.

But it wasn’t just poverty that sealed his fate early on. It was also poverty’s terrible inward twin: despair. Mansul’s father, grandfather, uncles, and neighbors all eked out a meager existence from the sea. And so, at a young age, too young in fact, Mansul surrendered to a gnawing sense of the inevitable.

“I thought it would be more useful to start earning early instead of going to school,” Mansul explained. “Why study if I would end up a fisherman too?”

But for his children, the fisherman, his face pitted and pockmarked with regret, now permits himself to dream. “I want Marsila to be good, like the other kids who go to school.” Mansul said. “She’s very bright. I can see that she understands the lessons right away, without the need for repetition.”

After class, Marsila practiced her writing under the watchful guidance of Teacher Sidang. Hers was a tiny world, radiating from their house to the edges of the mangrove forest, a tangled no man’s land where large crocodiles still lurked. For Marsila, each day with Teacher Sidang was a special occasion, a break from a daily life of planting cassava, playing with their cats, and being a dutiful daughter.

It wasn’t just Marsila’s vivacity that endeared her to Sidang. She had a kindness and concern that seemed preternatural for her age. These lessons meant so much to the young girl because she wasn’t just learning for herself.

She was passing on her precious knowledge to her illiterate parents too.

Marsila and her parents presently sat near the door of their single, shared room. It was fastidiously clean and well-ordered, an emerging theme in this community, as if it were a last defiance against the indignity of being poor. Marsila read her modules out aloud, pausing to allow her mother and father to follow along.

Ang mga sumusunod na larawan ay halimbawa ng kulay ng itim.

Madilim ang langit sa panahon ng bagyo.

Ilan pang halimbawa ng mga bagay na may kulay itim.

And what were these lessons for? In their advanced years, Marsila’s parents did not think this education would be useful for further employment. Bu it could prove handy in case they needed to sign documents, which, to the illiterate, can be a terrifying affair. And there was another reason why Marsila played the role of teacher in their household. It was late February, and while this remote community had not yet been gripped by the frenzy of catch phrases, campaign rallies, and colors of the fast approaching national elections, it was, nonetheless, a much anticipated affair.

Marsila, all of eight years old, was determined to teach her mama and papa how to vote on their own.

While overtly virtuous, her goal may seem trivial to an outsider. After all, there are laws in place to ensure that those who can neither read nor write would still be able to vote. Under the Omnibus Election Code of the Philippines, the illiterate or disabled may be “assisted by a relative, any person of his confidence in the same household, or certain members of the board of election inspectors” on the day of the polls.

But Marsila’s ambition reflects a larger aspiration for indigenous peoples in this region, a community that has had a wretched experience with elections and their right to suffrage.

“They are used for cheating operations, because they don’t understand what’s written on the ballot.” Arlene Sevilla, Tawi-Tawi civil society leader and a local college professor explained.

Sevilla said that in past elections, boatloads of Sama Laut, Badjao, and even Tausug would be brought to precincts all over the province to vote en masse. Corrupt assisters, who were mandated to help, would fill up the ballots for political benefactors instead. Coercion and bribes weren’t even required. The warm bodies were enough. And because many indigenous peoples here still did not have identification, lacking even a record of birth, they were also tricked into voting repeatedly, abused again and again. “Sometimes they are made to vote four or five times,” Sevilla said.

Sevilla, who coordinates various NGO education projects in BARMM, hopes that by improving literacy, these communities would have some level of protection against the treachery. “Little by little, we are trying to teach them to read and write so that they can identify the names and choose who they want to vote for,” she said.

Sidang continues to do her part, one house at a time. We made our way to another stilt house community, our boat puttering under a relentless, unslanted sun. Sidang shielded her eyes from the glare, her pink hijab fluttering softly in the breeze. “I’m a little tired,” she confessed. She took a sip from an almost empty water bottle.

We arrived at a cluster of homes linked by narrow wooden gangways. Eight children were already gathered in an open area, eager but well-behaved. Their parents, sitting in a loose huddle, were here for the lessons too. Presently, a middle-aged man moved closer to the children, settling behind one of the boys. This was father and son, learning to read and write together.

Two of Jusali Salapuddin’s children were also part of the class. The 37-year old fisherman was wearing his best shirt for the occasion, a white button-up with blue patterns, its wide, pointy collars a vestige from a bygone era of fashion. He had a sparse mustache and short, wavy hair that was overgrown at the sides. Sali, as he was known here, only finished two years of basic education. But unlike most members of his community, he knew how to read and write, albeit slowly and with a bit of effort. Now, he wanted to gift that knowledge to his kids too.

Sali was also one of the few in this group who could converse in Filipino, the national lingua franca. I sat beside him to chat, delighted by the fact that we didn’t need translators. “I’m sorry for my poor Filipino,” he said right away. “I’m sorry for my non-existent Tausug,” I replied. He smiled.

Sali spoke carefully and thoughtfully, as if measuring every word. I learned that his reading, writing, and especially his language skills were mostly self-taught. Instead of becoming discouraged after dropping out of school, Sali’s appetite for knowledge grew even sharper. He continued to practice reading and writing with the limited material they had at home. He could even read some English now, he said, although he didn’t know the meaning of the words.

When he started earning a bit of money for himself, Sali bought a transistor radio in a rare trip to Bongao. By listening to the programs, he learned to converse in Filipino. “I liked programs about work and livelihood,” he said. “But I especially liked listening to the news.”

But his prized transistor eventually broke, and with the growing needs of his family, he had not been able to save enough to buy a new one. Nowadays, whenever he had the chance, Sali would instead visit the only house in their cluster with a television set. The device was so rare that a small satellite dish on the roof of one’s house was a status symbol of sorts around here. If there were enough adults around, they would prevail on the children to switch the channel from cartoons, Sali said. He missed hearing the news.

“Why do you like watching the news?” I asked.

“Because I want to understand the world outside,” he said.

As it happens, the world Sali wants to understand is constantly changing. Sometimes it seems, at breakneck speeds. The global information landscape is no longer defined by transistor radios or televisions but by the internet, mobile phones, and social media.

The Philippines in particular is a social media madhouse, with tech behemoth Facebook in particular reporting almost complete usage penetration among Filipino internet users. Sali was not oblivious to these changes. Even here, despite poor coverage, some are still able to go online in miraculous pockets of reception at the highest points of the scattered islands.

But as wealth is created, roads are choked with cars, and bespoke drinks are ordered in cafes, Sali’s corner of the world, or rather, their circumstances, remains the same. The fisherman said this plainly, without a hint of bitterness or rancor. “People here say our country is poor, is that right?” Sali asked, as if he wasn’t sure that poverty was a widespread experience. “Well, I want our country to be prosperous.”

And now, another elections was looming. Sali and the others, despite decades of unfulfilled promises and neglect, were still keen to cast their vote. With lives that seemed perpetually adrift, twisting on fitful waters and helpless against the cold indifference of fate, this was one of the few things that seemed within their control. Making a choice. It was an anchor in rough seas, a proof of existence, a validation. Their voice could shape the nation’s destiny too. They mattered. This thing that comes around every three years had to matter, right? It was indefatigable hope, one they jealously protected.

“I want someone who can run this country well. I want to choose well,” Sali said. “But how can I do that if I know so little?”

Not everyone shared Sali’s ideals, not even in this small community. Elections in many parts of the country have been historically transactional, providing a crushing advantage to those with the most money, power, and influence.

NGO coordinator Sevilla believes in the transformative power of education in pursuing election reforms too. We met at the Buan Elementary School, situated at the highest point of the island barangay. It was their foundation day and a short program was organized to showcase the dancing talents of teachers and students alike. Small plastic bottles of soda and rice cakes were passed around, the sugary treats boosting the friendly atmosphere.

Beyond literacy and a grasp of current events, Sevilla believes that election education should be institutionalized and taught as early as elementary school. As a former poll clerk and member of the Board of Election Inspectors, she witnessed, first hand, the small-time corruption that distorts people’s attitudes toward politics. Elections, Sevilla noted, were known locally as harvest season or anihan, a time to collect money from politicians in exchange for votes, before they were forgotten once more until the next election cycle.

“I tell them, three years [before the next polls] is a long time. Will the 1000 pesos (20 USD) you received for your vote make up for all those years under a bad leader?” Sevilla said. “We should explain to people, especially kids, that votes that are given freely, to sincere and deserving candidates, will give them more prosperity in the long run.”

Sevilla acknowledged that such well-entrenched practices as vote buying will not go away quickly. Talk is cheap, especially for people with needs. But election education makes for better citizens in other ways, too. After all, what good is voting without proper discernment?

“When people know what their rights are, what basic social services they’re entitled to, they will learn to ask for it. Because if they don’t know their rights, they will not demand it,” Sevilla said. “They would just accept life as it is.”

But who will provide that education? Would those who benefit from the status quo lift a finger?

On May 9, 2022, Bongbong Marcos won the presidency in a landslide. It was the culmination of a bitter and combative campaign that saw supporters of Marcos and his closest rival, Vice President Leni Robredo, clashing passionately on social media.

On election day, not a few waited long hours in polling places after a more than usual number of Vote Counting Machines malfunctioned. Instead of entrusting their filled-up ballots to election officers who would feed them to the machines at a later time, many chose to wait and do it themselves, fearing fraud. Thousands of kilometers from the stilt house communities Sidang frequented, people were protective of their votes too.

Marcos won Tawi-Tawi by an overwhelming margin, getting over 82 percent of votes. In Barangay Buan, voter turnout was an astonishing 97 percent.

Robredo did not contest the election results, asking her supporters to “respect the decision of the majority.” Critics and observers however have raised concerns over possible election fraud, the alleged non-transparent Automated Election System, as well as the climate of disinformation that attended the polls. It was a campaign marked by the unmistakable rise of vloggers, influencers, aggressive memes, and emotionally-charged videos short on facts and long on hyperbole.

And so, while Sali lamented the scarcity of information in their small community, in other parts of the nation, people are drowning in it. Perhaps the two worlds are entangled. Perhaps the dearth and deluge of information are just two sides of the same, worrisome coin. Because a world where truth seemed optional, subject to clicks and likes, competing for our limited attention spans, is also same world in which profound inequalities still exist, giving rise to venomous dissatisfaction.

Marsila is spared the agony of self-reflection for now. Her father, Mansul, was able to vote in the last elections unassisted, a small victory for the family, and also Teacher Sidang. Before parting ways during our brief visit in February, I asked Marsila what she wanted to have in their home.

“A solar lamp!” she exclaimed. “I’m going to be a teacher, so I’ll need to read at night.”

“And also to keep away the scary monsters in the dark.”

In-depth special reports and features showcasing the best multimedia storytelling from GMA Integrated News.