We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

MARCH 31, 2022

Dr. Jacquiline Romero’s love for numbers was a result of an accident–one that, thousands of steps later, resulted in her becoming one of the most prominent rising talents in the field of science globally.

At seven years old, Jacquiline already liked mathematics, but it was only when her uncle, an engineering student then, brought home an algebra book that her world further expanded.

“One day, mayroon siyang dalang books, sabi niya mali raw ‘yung nabili niya. Tapos ‘yung book na ‘yun was problem solving in algebra. Noong binasa ko ‘yung book, I really got into it kasi natuwa ako na from english sentences, you could write mathematical equations and then from there solve the problem,” Jacquiline shared.

[One day, he had brought books with him, but he said he had bought the wrong books. And the book happened to be on problem-solving in algebra. When I read it, I really got into it because I was fascinated by how from English sentences, you could write mathematical equations and then from there solve the problem.]

She was fascinated at how if you could translate something mathematically, you could find a solution because there was already a recipe.

By the time she entered high school and encountered physics, “the language we describe the natural world with,” she was immediately drawn to it. She eventually decided to take up quantum physics because of a teacher of hers in high school who kept complaining that the field was “weird and hard.”

Out of curiosity, Jacquiline decided to research quantum physics and when she read article after article on what the science was about, she found her place under the sun.

By Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries’ definition, quantum physics is simply described as the branch of science that investigates the principles of quantum theory to understand the behavior of particles at the atomic and subatomic level, but Jacquiline sees more than that.

“Ang beauty kasi ng quantum physics is at the bottom of everything. You could think of chemistry, you can think of biology pero at the end, kapag ibe-breakdown mo siya sa pinaka basic na component niya, quantum physics ‘yung nandoon. And to me, that’s really beautiful,” Jacquiline said.

[The beauty of quantum physics is at the bottom of everything. You could think of chemistry, you can think of biology but in the end, if you break it down to its most basic component, you will find quantum physics. And to me, that’s really beautiful.]

Quantum physics, Jacquiline explained, is the “physics of information” and has helped give birth to technologies such as the photocopying machine and the MRI.

“Information as we know it right now, puwede nating isipin na napaka-abstract niya. You hear my voice because there are particles in the air that carry the waves that are coming from my vocal cords. So ‘yung information as we know it kahit na abstract ‘yung tingin natin sa kanya, ang basis talaga niya is some physical system. So lahat ng information natin embedded siya on a physical system,” she said.

[If I were to describe what quantum physics is, quantum physics is the physics of information. Information as we know it right now, we can think of it as really abstract, right? You hear my voice because there are particles in the air that carry the waves that are coming from my vocal cords. So that information as we know it, even if we think it’s abstract, there is a physical system there as its basis. That can be a carrier of information so all of our information is embedded in a physical system.]

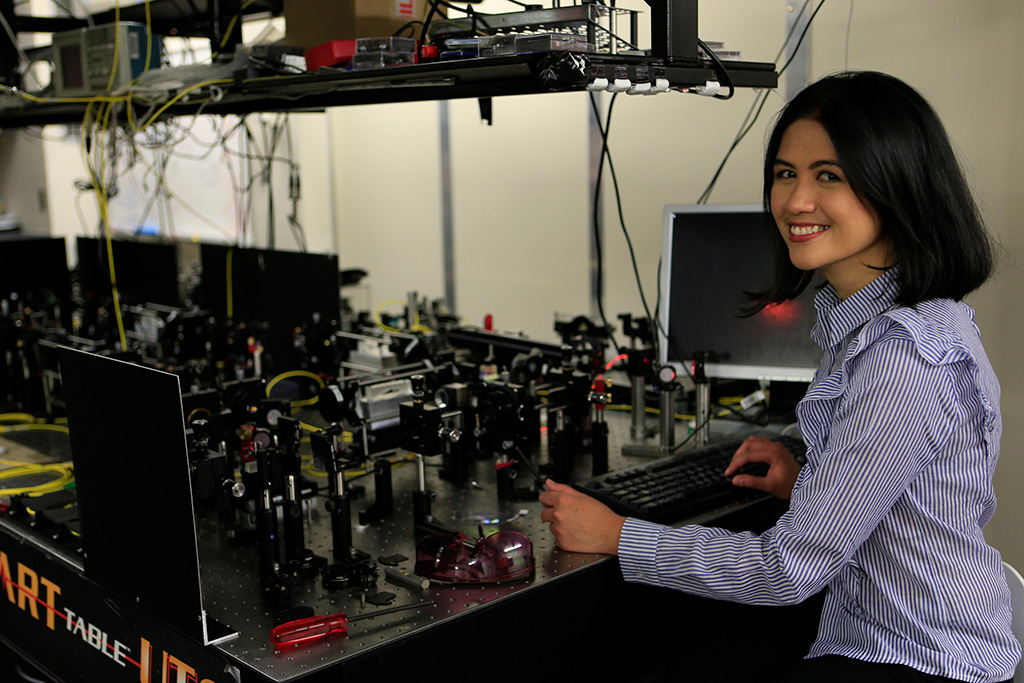

Around seven years ago, when Jacquiline studied at the University of Glasgow, she and her colleagues discovered that light can be slowed down in a near-vacuum even without touching it.

Although the speed of light is a cosmological constant, particularly made famous by Einstein’s theory of relativity, Jacquiline proved that light can become slower.

“When you look at your physics textbook and you look at what is the speed of light, usually it would tell you it’s 300,000 kilometers per second and that’s the end of the story,” she said. “In the work that we did, we were able to show that actually if you put some shape in that light, kunwari babaguhin mo imbes na ‘yung laser pointer mo dark spot lang siya, gagawin mo siyang kunwari mukhang donut ‘yung shape niya, puwede siyang bumagal.”

[When you look at your physics textbook and you look at what is the speed of light, usually it would tell you it’s 300,000 kilometers per second and that’s the end of the story. In the work that we did, we were able to show that actually if you put some shape in that light, instead of making your laser pointer into a dark spot, you turn it into a donut shape, it can slow down.]

“We were able to show that it slows down as much as I think 3,000 kilometers per second,” she added. “Fun experiment ‘yun kasi it was actually hard to do, really challenging. I think we spent more than two years doing that experiment.”

[We were able to show that it slows down as much as I think 3,000 kilometers per second. It was a fun experiment because it was actually hard to do, really challenging. I think we spent more than two years doing that experiment.]

Dr. Romero in her younger days

Before going to the University of Glasgow as a postdoctoral fellow and later becoming an associate professor at the University of Queensland, Jacquiline studied physics at the University of the Philippines for both her undergraduate and master’s degree.

Leaving the country, she soon realized, meant overcoming numerous struggles, not only because she was a woman but also because she was a Filipino.

“I think as a Filipino with a bad history of colonization, hindi mo namamalayan pero mayroon kang dalang baggage kapag lumabas ka. Noong umpisa hindi ako sure na 'Ah, alam ko naman magaling ako sa Pilipinas pero magaling din ba ako dito?' Kasi paglaki sa Pilipinas parang mayroon tayong implicit assumption na kapag foreign o kapag galing sa ibang bansa, magaling ‘yun,” she said.

[As a Filipino with a bad history of colonization, you don’t realize it but you carry baggage with you when you leave. In the beginning, I wasn’t sure. I thought, ‘I know I’m good in the Philippines, but am I good here?’ Because when we’re raised in the Philippines, we have this implicit assumption that if it’s a foreigner or they come from a different country, they’re good.]

She also experienced a cultural barrier, especially since she felt that as Filipinos, we were raised to be polite. But being too polite, she learned, often worked against us at different times.

“When you’re in a scientific discussion like that, what often could happen is if you’re very polite, you don’t get to say what you want to say… So dapat i-prioritize mo kung ano ‘yung gusto mong sabihin. Even if it means na you let go of that politeness na sanay ka sa sarili mong kultura,” she added.

[When you’re in a scientific discussion like that, what often could happen is if you’re very polite, you don’t get to say what you want to say. You have to prioritize what you want to say, even if it means you have to let go of that politeness that we’re used to in our culture.]

Dr. Romero at work

Back in the Philippines, when she was still studying physics, Jacquiline shared that she didn’t feel the divide between men and women in the field of science and didn’t feel any discrimination when she was studying in the country. Things changed when she moved abroad.

“Ang maganda sa Pilipinas nasa kultura natin na pahalagahan ang pag-aaral… At saka ‘yung hindi tinitingnan kung ano ‘yung kasarian mo. Hindi ko talaga na experience ‘yung iba ako dahil babae ako noong sa Pilipinas ako. Kahit tingnan mo ‘yung batch namin, talagang marami ring babae, marami ring lalaki, pero hindi namin ramdam ‘yung pagkakaiba na ‘yun,” she said.

[The beauty of the Philippines is it’s in our culture to value education…and we don’t look at gender. I really didn’t experience that I was different because I was a woman when I was in the Philippines. Looking at our batch, there were also a lot of girls and boys and we didn’t feel the difference.]

In the past years, Jacquiline has experienced mansplaining from male colleagues, even if she was already fully and wholly well-versed in the topics they would condescendingly explain to her.

“Ine-explain nila pero naaalala ko ‘yung feeling na ‘Nye, bakit mo ‘yan ine-explain sakin?’” she revealed. “Sabihin mo lang, ‘Ah okay. I already know that. So tell me about this one.’...I usually just let it go.”

[They explain it to me and I remember feeling, ‘Nye, why do you think you have to explain that to me.’]

She would also experience sitting through talks presented by a man and a woman and hearing the audience comment that the male speaker was better than the female speaker even though both were equally good.

“Pareho lang naman. ‘Yung may ganun na may expectation ka, ‘Ay, babae siya. Less ‘yung technical knowledge niya,’” she said.

[It’s the same. There are expectations like, ‘Ay, she’s a woman. She has less technical knowledge.’]

Dr. Romero as one of L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science (FWIS) International Rising Talents

Currently, Jacquiline shared that she was part of the Center of Excellence for Engineered Quantum Physics in Australia and they recently opened up women-only scholarships because they are aware that the field is male-dominated. In her department alone, Jacquiline shared that there were four times more men than women.

“Bakit walang babae sa physics, ‘di ba? And it really boils down to expectations. When you look at the list of really good physicists, you’d think of Heisenberg, Schrödinger, you’d think of men. Wala kang role model except for a few. Very few ‘yung babae sa physics. So we’re really trying hard to work para mas dumami ‘yung babae sa physics,” Jacquiline explained.

[Why are there no women in physics, right? And it really boils down to the expectations. When you look at the list of really good physicists, you’d think of Heisenberg, Schrödinger, you’d think of men. You don’t have role models except for a few. There are few women in physics. So we’re really trying hard to work so there would be more women in physics.]

Having this unconscious bias, Jacquiline shared, is a complex problem that one person alone could not change, but there are small collective steps we could take as a society to become more inclusive, such as conducting unconscious bias training and comparing individuals’ records relative to the opportunities given to them.

Dr. Romero has won numerous awards for her work

After being named one of L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science (FWIS) International Rising Talents and all of her remarkable achievements and discoveries in the field of quantum physics, Jacquiline still considers being a role model as her greatest work.

The quantum physicist said, “I am most proud of being a role model for aspiring young Filipina scientists kasi naaalala ko noong nagde-decide ako ano ba ‘yung gusto ko na gawin, na gusto kong maging quantum physicist, wala akong makita na Filipino na masasabi kong, ‘Ah siya, gagayahin ko siya.’ So, I’m most proud that now I could be that role model for younger people na pwede nila sabihin na ‘Pwede ko siyang gayahin.’”

[I am most proud of being a role model for aspiring young Filipina scientists because I remember when I was deciding what I wanted to do, that I wanted to be a quantum physicist, I couldn’t think of a Filipino where I’d say, ‘Ah her. I want to be her.’ So, I’m most proud that now I could be that role model for younger people that they can say, ‘I can become like her.’]

At first, Chezka Carandang didn’t want to become a pilot. She wanted to become an actress.

“Noong bata ako gusto ko talagang maging artista so nag-try din ako mag-modeling and sumali din ako sa mga beauty pageants before para to gain more experience, more exposure and then na-realize ko na, it’s not for me,” Chezka, now a first officer at one of the largest airlines in the Philippines, said.

[When I was a kid, I wanted to become an actress so I tried out modeling and joining beauty pageants to gain more experience and exposure, but I realized that it really wasn’t for me.]

After graduating from college with a degree in Communication Arts, it slowly dawned on Chezka what she truly wanted to do and where her true vocation lay–traveling.

At first, her parents suggested she become a pilot although they were still hesitant since there weren’t a lot of female pilots in the country. Everything changed, however, when Chezka finally entered a plane’s cockpit. As she saw the switches and controls light up with the skies horizon in front of her, she immediately knew what and who she wanted to be.

“I still remember,” Chezka shared, “na sobrang sabi ko, ‘Wow. Ito na talaga ‘yung gusto ko.”

[I still remember saying to myself, ‘Wow. This is what I really want to do.] Despite the uncertainties and the doubts, Chezka carved her path in the field of aviation, hoping someday, she would find her permanent place in the cockpit, wheel at hand, and travel the world.

To learn more about working in the airline industry and ask pilots about their journey, Chezka’s parents suggested she train first as a flight attendant.

She said, “Before parang limited lang ‘yung information natin sa internet so I think that’s the only place and time na best for me to ask questions about flying and ‘yung mga firsthand experience nu’ng female pilots.”

[Before information about it on the internet was limited so I think that’s the best place and time for me to ask questions about flying and the firsthand experience of female pilots.]

Chezka Carandang during flight training

It was hard, Chezka recalled, training to become a flight attendant, but after six months of working as a flight attendant, Chezka felt that she was ready to learn to become a pilot already.

Although she was the only girl in her class of around 10 pilot students, Chezka’s purpose didn’t waver.

Her classmates were supportive, Chezka shared, and were all passionate about aviation that they helped each other out in reaching their full potential.

Chezka revealed that what challenged her during her pilot training was overcoming her self-doubt and having stronger faith in herself. Despite the doubts, by 2016, Chezka was officially a pilot.

“Sobrang proud ako ‘yung ‘pag pursue ko on being a pilot. It was a hard time in my life kasi I was still figuring out myself, what I wanted to do in life. So, good thing my family, especially my mom supported me all the way,” she said.

[I’m so proud I pursued being a pilot. It was a hard time in my life because I was still figuring out myself and what I wanted to do in my life. So the good thing is my family, especially my mom, supported me all the way.]

Chezka Carandang inside the cockpit

Chezka felt blessed to be a part of a generation that didn’t discriminate against her based on her gender, but she shared that she would still encounter rude and discriminatory remarks from clients from time to time.

“There was one time may nag-comment I cannot forget kasi he said, ‘‘Pag babae ‘yung pilot, hindi ako sasakay,’” Chezka said.

[I cannot forget, there was one time someone commented, “If the pilot is a woman, I won’t ride the plane.]

There was also another time, the pilot shared, when people mistakenly thought she was part of the crew while welcoming clients inside the aircraft.

Chezka Carandang at work

She admits she was offended, but she just lets it go. "Kahit saan namang company or profession people already have less expectations of women kaya I'm challenged to prove them wrong na we are equally capable."

[In whatever company or profession, people already have less expectations of women that's why I'm challenged to prove them wrong and prove that we are equally capable."

"We undergo competency checks and we undergo the same proficiency checks. Flight trainings are also the same so that proves that we can be just as competent as our male counterparts," Chezka said.

Chezka Carandang with colleagues

To share her knowledge and inspire other women who also wish to become pilots, Chezka decided to create her own YouTube channel and TikTok account.

“So iniisip ko, ‘Why not be educational, why not share my experiences?’ Kasi before kaya lang naman ako nag-flight attendant kasi to gain information, data, and experience and kailangan ko matanong sila [female pilots] firsthand,” Chezka said. “Why not ako ‘yung puntahan nila if may mga questions sila for being a pilot here in the Philippines? Kasi ako no’n before nahirapan eh.”

[So I thought, ‘Why not be educational, why not share my experiences?’ Because before, the only reason why I became a flight attendant was to gain information, data, and experience and I had to ask them [female pilots] firsthand. Why not put myself out there so I can answer women if they have questions about being a pilot here in the Philippines? Because I had a hard time before.]

The pilot inside her aircraft

Surprisingly, Chezka said that there were more and more people who showed interest in becoming a pilot. After almost two years of creating content about her journey to becoming a pilot, Chezka has garnered more than 252,000 subscribers on YouTube and even 1.8 million followers on TikTok.

As she continues to fly to her heart's desire and bring along as many women as she can through 15-second and 5-minute videos, she proves that the sky's the limit for women in aviation.

The road to becoming a registered electrical engineer was not smooth, Lynne Gonzales shared.

Lynne, a 26-year old Ivatan, was born in Batanes and was raised by a single mother. Even though she was just a child, she was already aware of the discrimination she was made to feel all because she was illegitimate.

“May mga times noon na sinasabihan akong salot dahil anak ako sa labas,” Lynne shared. “’Yung nagsabi sakin ng salot, masakit siya kasi malapit pa siya sa pamilya.”

[There were times when people said I was a plague to society because I was an illegitimate child. What that person said to me hurt because they were also close to my family.]

Her childhood was also not free from financial struggles, especially since her mother didn’t have a permanent job and they had to live with Lynne’s grandparents to get by.

“‘Yun ‘yung pinaghugutan ko ng lakas para sabi ko sa sarili ko, ‘Someday, papatunayan ko sa kanila na may mararating ako sa buhay. And then someday, ibibili ko ng lote at igagawa ko ng bahay ang aking pamilya,’” Lynne said.

[That’s where I draw my strength and I tell myself, ‘Someday, I’ll prove to them that I’ll be successful. Someday, I’ll be able to buy and build a home for my family.]

“Gusto ko bigyan ng pride si mama na hindi lang puro pambabatikos ’yung maririnig niya. Someday, igagalang nila siya at ibabato naman sa kanya yung congratulations,” she added. “Kahit na single mom siya, nakapagpalaki siya ng anak na may narating sa buhay.”

[I want my mom to be proud and it won’t just be insults she’ll hear. Someday, people will respect her and it’ll be congratulations she’ll hear next. Even though she’s a single mom, she was able to raise a child who got to places.]

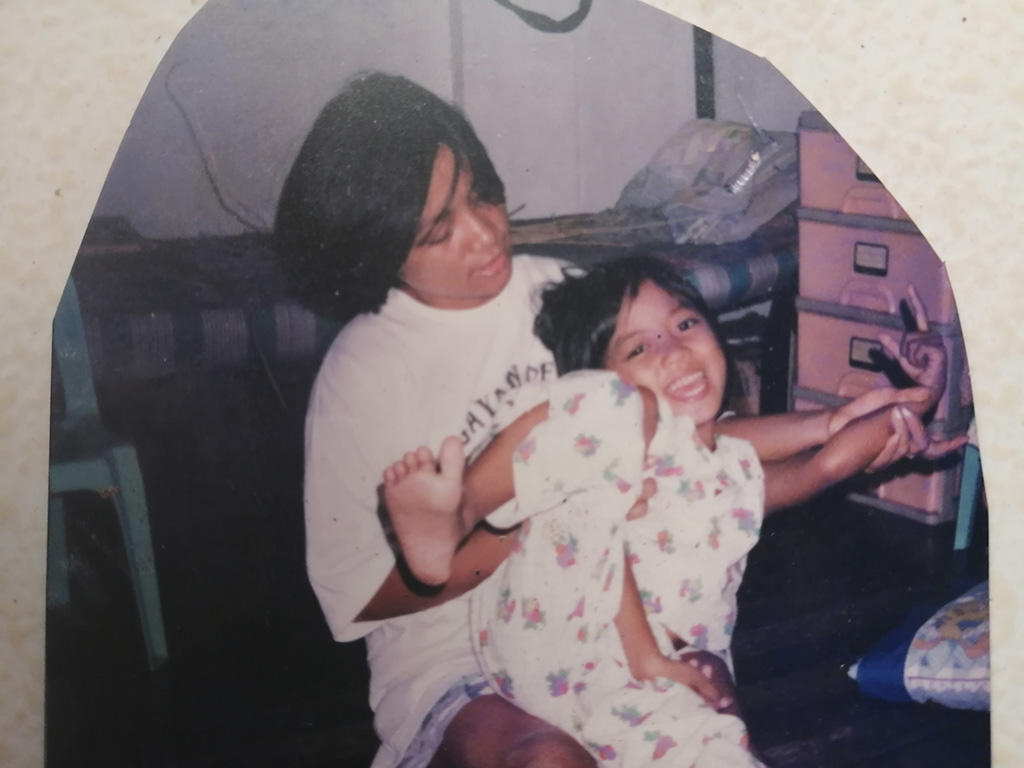

Young Lynne Gonzales with her mother

Lynne had originally wanted to become a civil engineer but the scholarship she received only allowed her to enter a Commission on Higher Education-priority course. Soon, she found herself enrolled as an electrical engineering student.

“Wala akong ka ide-ideya noon kung ano ‘yung electrical engineering pero nag-go na lang ako basta engineering siya,” Lynne revealed.

[I didn’t have a clue what electrical engineering was back then but I just went with it as long as it was still in the field of engineering.]

Finishing her college degree was an entirely different challenge since her mom couldn’t fully support her financially. She had to ask for help from different people.

“A lot of Ivatan makaka-relate po sa kwento ko. ‘Yung iba po siguro mas matindi pa ‘yung mga pinagdaanan. Given na limited ‘yung courses namin sa Batanes, kailangan po talaga namin lumuwas para makapag-aral,” Lynne said.

[A lot of Ivatan can relate to my story. Others might have had it worse. Since we only had limited courses in Batanes, we really had to get out just to study.]

“Kasi walang permanenteng trabaho ‘yung nanay ko so may mga times na nakikikain ako sa boardmates ko. Buti mababait ‘yung boardmates ko,” she added.

[Because my mom didn’t have a permanent job, there were times it was my boardmates who fed me. It’s a good thing they were kind.]

Lynne Gonzales with a fellow Ivatan during her college days

During her college days, Lynne remembered eating one can of sardines in a day just to get by.

“Pinagkakasya ko na ‘yun na ulam sa isang araw so may madalas once or twice lang po ako nakakain nun sa isang araw,” she said. “Minsan sakto ‘yung budget. Madalas kulang kaya I have to implement belt-tightening measures para maka-survive ako sa pang araw-araw ko sa Maynila.”

[That’s what I’d eat in a day so most of the time I’d only eat once or twice a day. Sometimes, my money was just right on track with my budget. Most of the time, I didn’t have enough. That’s why I had to implement belt-tightening measures so I could survive in my everyday life in Manila.]

She almost had to stop her education entirely when she was in her 5th year in college because she could feel that her mom could no longer provide any more funds.

Fortunately, Lynne’s fellow Ivatan friend, who was also pursuing an engineering degree, offered to give her shelter and help her out.

“In-offeran niya ako na tumira sa kanila ng libre dahil alam niya yung sitwasyon namin noon. ‘Yung 5th year ko hanggang sa nag-review ako at hanggang sa pumasa na ako ng board exam pinatira nila ako sa kanila ng libre,” she said.

[She offered to stay with her because she knew of my situation then. From my 5th year in college to the time I had to review and later on passed the board, she let me stay there.]

Lynne Gonzales at work

When she finally became a registered electrical engineer, she knew she wanted to go back to Batanes and help her people.

Lynne then started working at Batanelco in 2017 where she was in charge of overseeing its operations and maintenance. As an electrical engineer, Lynne worked on making sure the people had seamless access to something very essential to our lives but often overlooked–electricity.

“Ang duty namin aside from the regular office hours ay on-call po ako,” Lynne shared. “Feeling ko noon, ‘yung katawan ko konektado na siya sa distribution system kasi ‘pag nag-brownout kahit madaling araw, himbing na himbing tulog mo, ‘yung katawan mo na mismong gumigising tapos babangon ka na tapos kailangan tumulong ka sa restoration.”

[Aside from the regular office hours, it’s our duty to be on-call. Back then, I felt like my body was connected to our very distribution system because every time there was a brownout, even if it’s late in the evening when you’re fast asleep, my body wakes up on its own and I’ll just get up and help with the restoration.]

She added, “Sa panahon ngayon, napakahalaga ng electricity. Masasabi na nating essential siya, essential sa pang-araw araw na pamumuhay and at the same time sa development ng isang community.”

[Nowadays, electricity is so important. It’s essential, essential in our everyday life and in community development.]

Lynne Gonzales after the Itbayat earthquake in 2019

Aftermath of super typhoon Kiko

There were days, Lynne shared, that her job became more challenging, especially during disasters.

During the aftermath of the Itbayat earthquake in 2019, Lynne had to lead the task force on power restoration and damage assessment. It was extremely crucial, she shared, since the cables in Itbayat are installed underground to protect from the frequent typhoons that hit Batanes.

It didn’t help that they could feel the clock running. Since water and telecommunications were heavily dependent on electricity, they had to rush the restoration. Lynne said that fortunately, they were able to restore the power in time and provided lighting and outlets to the people who evacuated in their plaza.

Super typhoon Kiko in 2021 was an entirely different story, said Lynne.

During her site inspection after the disaster, the first case of COVID-19 community transmission was reported. Then, a surge followed.

“Nagka-COVID-19 din ako tapos ang nakakalungkot doon, nasa quarantine facility ako after ng bagyo so walang tubig, walang kuryente, wala o mahina yung signal,” Lynne shared.

[I also had COVID-19 and the sad part was I was in a quarantine facility after the typhoon so there was no water, no electricity, and barely-there signal.]

Thinking of the different ways she could help out despite her condition, Lynne decided to take charge of handling power restoration updates and other reportorial requirements for the area’s rehabilitation.

Despite the hardships, Lynne knew it was all worth it, especially when she could serve the people of her province.

Lynne said, “‘Yung goal ko nga po ay bumalik ng Batanes. Sino pa ba dapat ‘yung unang babalik at tutulong sa development ng aming probinsya kundi kami rin na mga Ivatana?”

[My goal was to go back to Batanes. Who else should first come back and help the development of our province but us, Ivatans, as well?]

It was always her dream, Lynne shared, to give back to the people who helped her get to where she was now. From the different individuals who offered a hand to her and her mom when she was just in high school, to the people who gave financial aid when she was struggling in college.

Lynne said. “‘Yun ‘yung dinadala ko in every aspect of my life na kahit na gaano kataas ‘yung tagumpay mo, hinding-hindi ka dapat nakakalimot sa lahat ng tao behind your success kasi wala ka naman doon sa level na ‘yun kung hindi dahil sa kahit konting tulong nila.”

[That’s what I bring with me in every aspect of my life that no matter how far I’ve come, I should never forget the people behind my success because I would have never reached that level if it weren’t for those people who helped me.]

Lynne Gonzales in Batanes

In Batanes, Lynne shared that they don’t necessarily discriminate based on gender and that people even express their amazement when they see a woman in a male-dominated field.

Even when she was studying, when there were only eight women and more than 40 men in their class, Lynne said that she didn’t feel any difference.

However, it was a whole different case whenever Lynne would go to site inspections and interact with clients.

“Minsan noong pumunta kami sa site inspection, siguro hindi nila intention na iparinig sa akin, sabi niya, ‘Ah, ‘yan ‘yung engineer niyo? Babae pala. Kaya niya ‘yan? Alam ba niya yung ginagawa niya?’”

[Once when we went to a site inspection, I guess it wasn’t their intention to let me hear it, the person said, ‘Ah, that’s your engineer? I didn’t know she was a woman. Can she do it? Does she know what she’s doing?]

Lynne Gonzales in college

“Tapos may mga times din na they question ‘yung judgement ko. Hindi sila maniniwala hangga’t hindi sinasabi ng kasama kong lineman,” she added.

[There were also times they’d question my judgment. They won’t believe me unless it’s the lineman I’m with who says it.]

There was also a time, Lynne shared, when kids would see her during site inspection and they would assume that she was only wearing a hard hat on because she was just copying the others.

“Kahit sa mga bata,” Lynne realized, “may trabahong identified na parang panlalaki lang.”

[Even among the kids, there are already jobs perceived as for males only.]

The engineer at work

Now working on becoming a professional electrical engineer, Lynne plans on building a house for her mom and helping fellow Ivatan reach their goals, especially those facing financial struggles.

Becoming an Ivatan woman in STEM, Lynne revealed, continues to be her greatest pride.

“Showing what I can do ay nagpapatunay na malayo ‘yung mararating ng pagiging resilient namin and napapatunayan na kayang kaya na kahit sinong kababaihang Ivatan,” Lynne said.

[Showing what I can do proves that our resilience can go a long way and it proves that any Ivatan woman can do the same.]

She added, “Hindi ko kailangan patunayan na ako ‘yung pinakamagaling. By just being here, unti-unti nating nabre-break ‘yung stigma and unti-unti nating nae-establish ‘yung kakayahan ng kababaihan.”

[I don’t have to prove I’m the best. Just by being here, we’re already slowly breaking the stigma and we’re slowly establishing what women are capable of.]

According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2020, the Philippines is the most gender-equal country in Asia, although it dropped eight notches and only placed 16th among 153 countries.

However, this may not be the reality for women in the field of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics in the country, especially since the profession has been known to be male-dominated around the world.

“There is a gender gap in the field of STEM in the Philippines,” sociologist Athena Presto shared.

According to the sociologist, women have low labor force participation in masculinized occupations such as engineering and technology.

These occupations, Athena explained, are only made to be masculine in terms of the privileges, the rewards, the hiring, and promotion process, and the lack of checks and balances for gender equality, not because they are inherently masculine.

In 2021, the World of Intellectual Property Organization indicated that the Philippines is the second leading country with the most number of female inventors, which, from a first look, could be a good indicator for Filipino female inventors, but the reality on the ground may still be different, Athena said.

“Imagine mo ‘yun ah, ang ganda nung sinasabi noon eh, kasi patent application, right? So, you want to have ownership of your own invention. Napakatagal na niyang sinasabi na ang baba ng leadership at managerial position na ino-occupy ng mga babae… So wala silang say kasi wala sila doon sa decision-making positions. It says a lot that now we have women actually applying for patent scholarships na gusto nilang angkinin ‘yung sarili nilang imbensyon,” Athena said.

[Imagine that, it said something really beautiful because it’s about patent application, right? So you want to have ownership of your own invention. It’s been said for so long. There is a low amount of leadership and managerial positions occupied by women… So they don’t have a say in decision-making positions. It says a lot that now we have women actually applying for patent scholarships, that they want to own their inventions.]

According to the sociologist, the gender gap in the field of STEM is a consequence of many factors, including our own culture and laws which are “inherently connected to one another.”

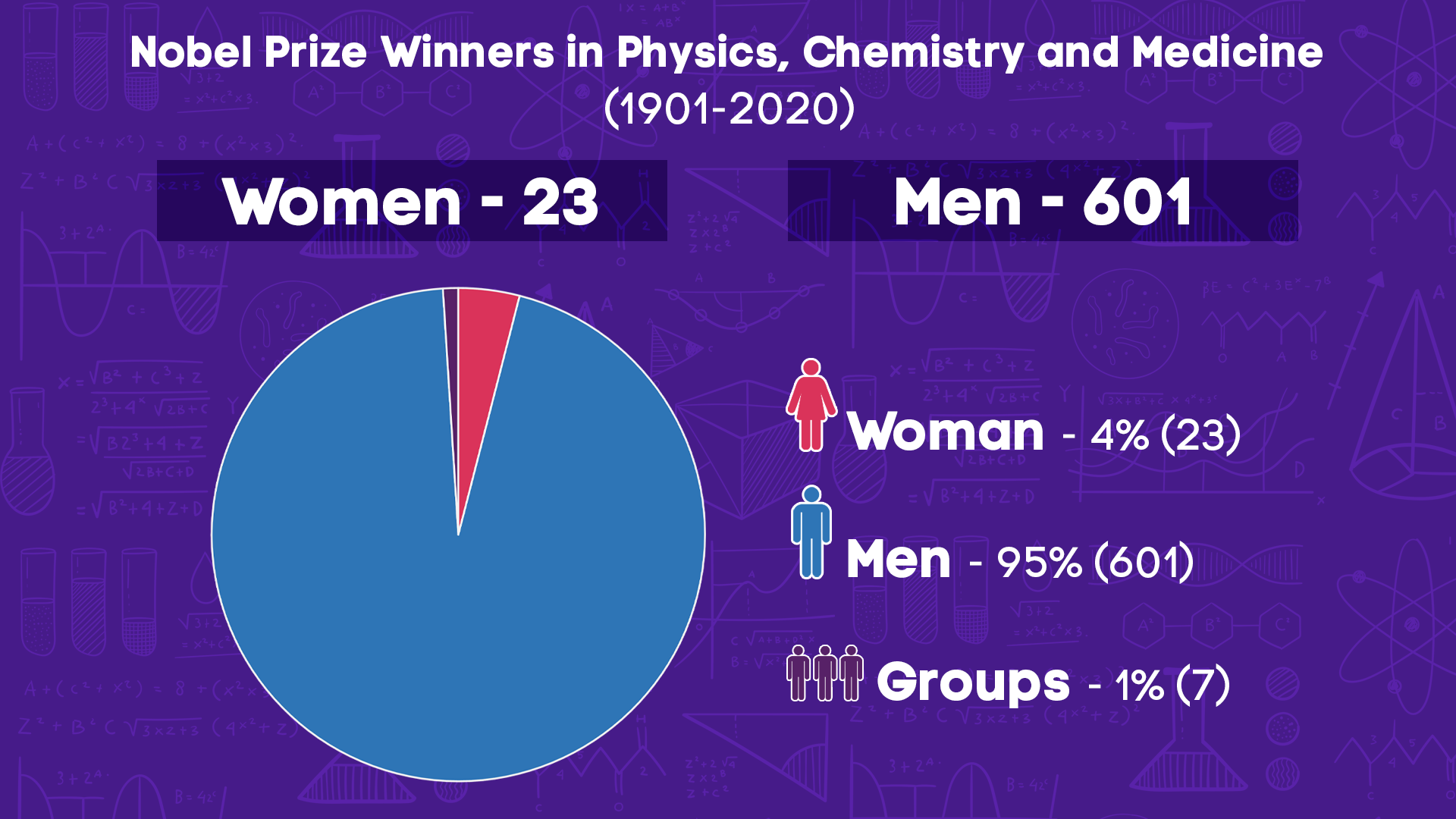

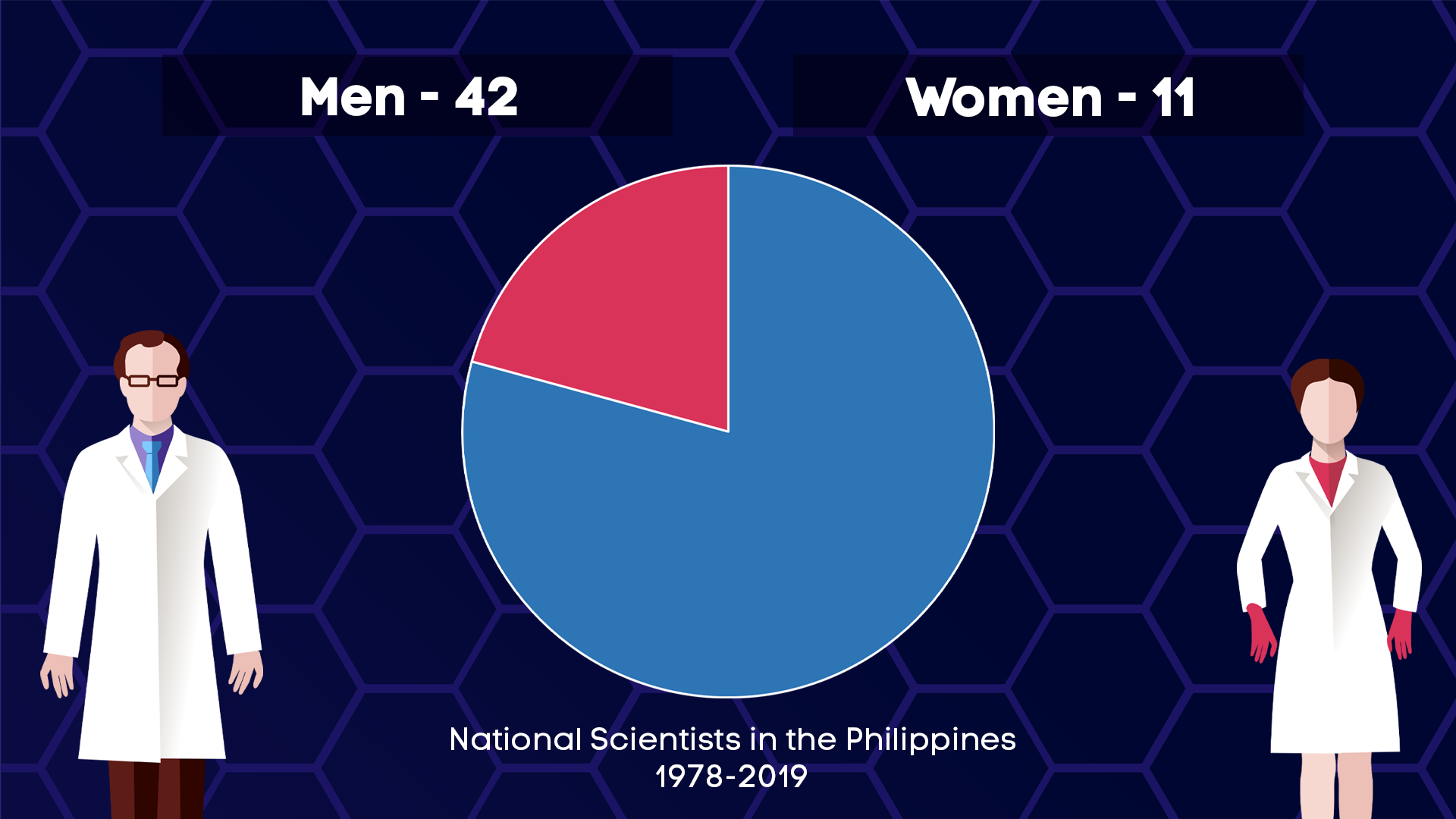

Source: Statistica

Linartes Viloria, the national project coordinator of the International Labour Organization’s Women in STEM Workforce Readiness and Development Program, said that women don’t see STEM as their first choice simply because of the social norms that indicate that it’s not the usual career path women take.

“The number of men in college courses in STEM really comes from the gender stereotypes, because if you already had those gender stereotypes about STEM, that carries over with the selection of your college course.”

In the school year 2016-2017, only 29.3% of students enrolled in engineering and technology courses were women, according to the Commission on Higher Education.

The laws we have at present, said Athena, also enforce these biases. Although we have laws that protect and uphold women in the workplace like implementing maternal benefits, we don’t have laws that “actually promote the participation of women in traditionally male-dominated cases.”

She added that in the field of STEM, our laws simply ensure that women can perform their traditional work at home while still being able to be paid for their work in professional settings.

Only 11 women have been named national scientists

“I think napaka importante din i-connect ‘yung mga babaeng nasa STEM field ngayon doon sa mga younger generations kasi sila ‘yung magsisilbing role model na ‘pag nakita ng mga kabataan na may mga ganito, ‘Kaya ko pala, kaya pala ng babae. Magiging successful din naman pala ako sa ganyan field.’ Mas maraming mae-encourage na kabataan,” Athena said.

[I think it’s also important that we connect women in the STEM field now to our younger generation because they will serve as their role models, and when these young girls see, they’ll say, ‘I can also do it. Women can actually do it. I can also be successful in that field.’ More young women will be encouraged.]

By celebrating women in STEM, Linartes shared that we can begin normalizing the space women occupy in the field.

“The more women in STEM we celebrate, the more we show women out there that being a woman in STEM is normal rather than exceptional,” Linartes said “You realize how numerous the different options are. Of course, there are still challenges they face along the way but hearing from these women makes it more relatable.

“So I think it’s also the role to highlight these milestones that women are making in STEM so that other women will also pick up from there and also make their own milestones as well,” she added.