By LOU ALBANO

Photos by DANNY PATA

Layout by JANNIELYN ANN BIGTAS

December 30, 2021

As Metro Manila contended with the world’s longest COVID-19 lockdown, Anton Umali knew he had to escape.

“The city was beginning to feel claustrophobic,” the 31-year-old writer told GMA News Online.

As the restrictions began to ease, Anton and his wife Marla began to look for a place outside the city. They soon settled in Laguna: it was still close enough to Manila where they worked, but far removed from the heavy gray reality of the city.

But the couple was far from alone, says urban planner and landscape architect Paulo Alcazaren.

“It’s still all anecdotal, but the sales of properties at the edges of Metro Manila and beyond — past Muntinlupa and Bulacan — appear to have gone up,” he told GMA News Online.

“Those who can afford have moved out and stayed out of the metro.”

For Anton, it was simply a chance to take a deep breath.

“There aren’t any green places in Metro Manila, and spots for fresh air weren’t easily accessible. We had to go out of our way to access the natural, which is more important and feels like a basic right given the times,” he said.

There’s more to green open spaces than simply keeping people’s mental well-being in check. Parks, as it turns out, can also help in improving people’s physical health. Even just exposure to green and natural environments, studies say, can help reduce incidents of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity. Proximity to nature also encourages healthier behavior and exercise.

Green open spaces are so important to people’s health that the World Health Organization has set a target of nine square meters of green per person. In fact, having parks within a 10 minute walking distance is said to be the most ideal.

An aerial photo shows the severe lack of green spaces in a large swath of metro manila. paulo alcazaren

Unfortunately, this is far from the case for the 13 million residents of Metro Manila.

With only Rizal Park and Paco Park in Manila, Quezon City’s University of the Philippines Diliman Campus greenery, the Ninoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife, the Quezon Memorial Circle, and La Mesa Ecopark, which hardly counts because that’s more a watershed than a green open space, residents of the National Capital Region would need to travel far to access a park.

And there is not nearly enough of them, with Metro Manila “at 1 square meter per person, and that’s being generous,” Alcazaren said.

It’s a startling realization, especially when the bleak reality is made visual. On his Facebook page, Alcazaren posted an aerial shot of a portion of Metro Manila, choking with so much concrete.

“We need over a thousand hectares of park and open space for our current population,” he said.

The photo showed four large green open spaces: two golf courses, the National Center for Mental Health, and the American Cemetery. It was far from sufficient. The photo quickly went viral.

More green spaces, such as Paco Park in Manila, has numerous benefits for residents.

Since moving to Laguna, Anton has started running outdoors again. “It was something I could do in Manila, but always with the risk of getting side-swiped by cars,” he said. The greenery around him has also made the activity a lot more enjoyable. “There’s no pollution here.”

Indeed, the air situation in Metro Manila is quite dire. In parts of NCR, in fact, residents should have been wearing a mask even before the pandemic because of poor air quality. In Valenzuela City, the air quality index (AQI) had already reached a dangerous 176 in 2019. The United States Environmental Protection agency pegs healthy AQI value at less than 100.

Enough green spaces can help solve a city’s air pollution problem two ways. First, trees are natural air filters. In its lifetime, a single tree can absorb carbon from 42,000 vehicles.

Foliage also encourages active transport, which means that, to some extent, green spaces could help lower carbon emission in a city. While green open spaces alone won’t convince motorists to swap their cars for bikes, having ample natural factors in the city can most certainly help promote it.

According to Alcazaren, “wide sidewalks and streetscapes with trees are green in terms of the physical umbrella they provide, as well as in terms of encouraging biking and walking as an alternative to our problematic transport system.”

Iloilo, for instance, with its protected bike lanes, interconnected networks, and the famous 9km Esplanade — incidentally designed by Alcazaren’s firm PGAA Creative Design — boasts of a strong cycling culture among its residents. It was most recently named the Most Bikeable City in the Visayas region, as well as the entire country in the recent Mobility Awards.

In a 2018 documentary, Howie Severino highlighted the importance of arroceros forest park, Manila's last lung.

Aside from air quality, green open spaces can also help mitigate heat, especially during summer. During the strictest lockdowns, with people having no access to malls and their air-conditioning, many NCR residents were forced to feel the summer heat in its full unforgiving glory.

In the city, it becomes even more punishing thanks to the Urban Heat Island Effect, which leads to elevated temperature as the urban landscape trades in natural elements like trees and soil for cement, asphalt, and concrete.

Unlike soil that allows heat to escape, pavements, roads, and buildings absorb and retain heat, which then lead to more uncomfortable temperatures. More incidents of heat strokes and dehydration can be expected.

Apart from the soil’s ability to release heat and the relief that tree shades provide, plants also have a natural cooling effect, a result of what experts call the evaporative cooling process.

In a documentary about Arroceros Forest Park, the last lung of Manila, journalist Howie Severino demonstrated this cooling effect by placing a thermometer inside the forest park, and another thermometer just outside.

Inside the forest park, the temperature was two degrees cooler than outside the forest park.

The cooling relief provided by green open spaces are not just welcome, it’s almost necessary given rapid urbanization and infrastructure agenda like this administration’s robust Build Build Build program that nearly assures urban heat island.

Roads, pavement, buildings absorb heat, leading to an Urban Heat Island effect.

Parks don’t just address extreme summer heat. During rainy season, green open spaces can also address flooding, thanks to soil that can absorb rainfall.

“So long as cities have green open spaces, they can act as a sponge and absorb and delay the runoff before flushing it out,” Alcazaren said.

In recent years, and even from just short bursts of rain, motorists and commuters have experienced flooding in portions of Metro Manila.

Pools of stormwater runoff emerge at overpass landings, sporadic splashes of water from flyovers surprise motorists at ground level, and even pedestrians are not spared from flooded walkways even when elevated.

According to Dr. Marla Redillas, Division Head of Hydraulics and Water Resources of the Department of Civil Engineering of De La Salle University, Metro Manila is so developed, it’s become too impervious: no more infiltration happens.

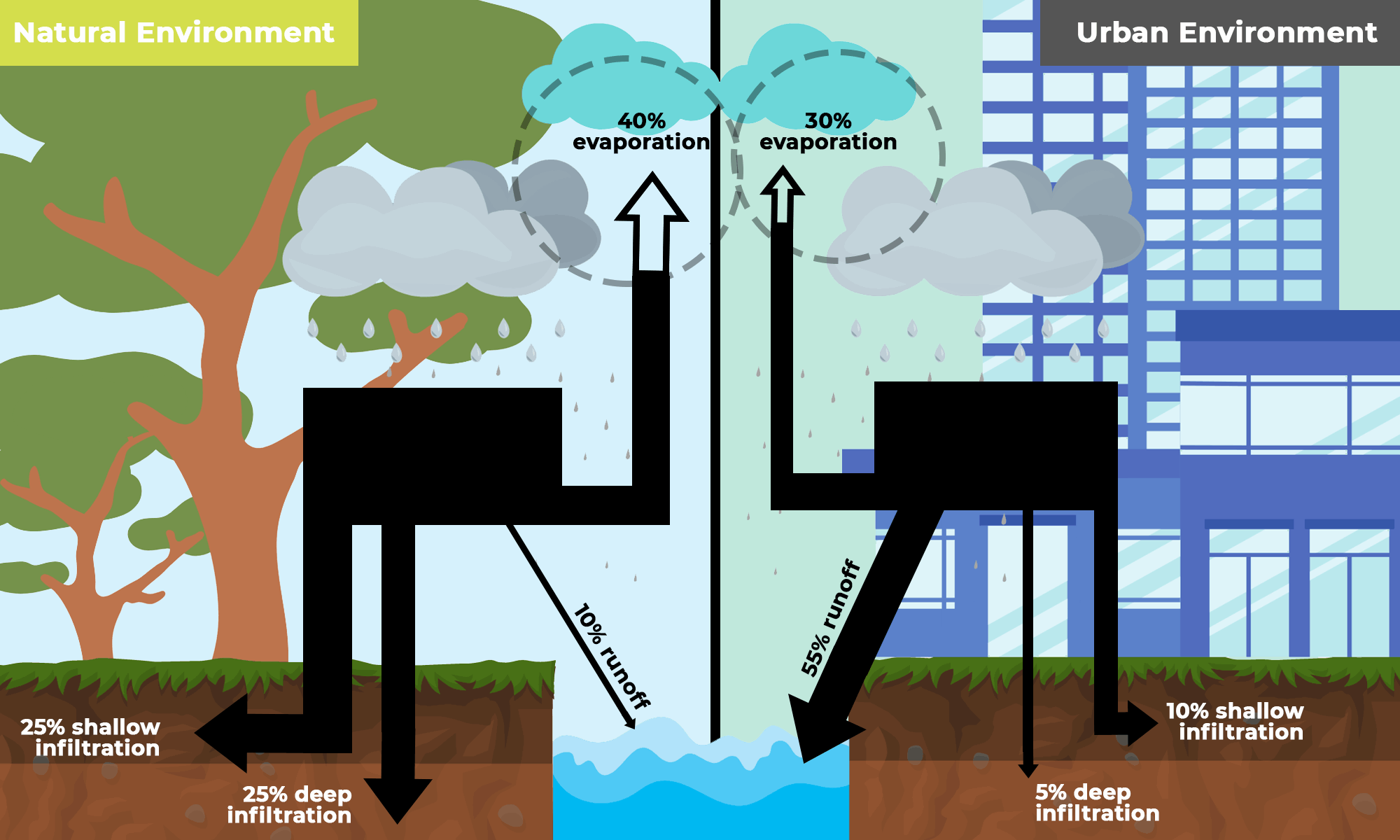

The Urban environment disrupts the natural water cycle, leading to more water runoff, which leads to flooding.

Infiltration is when stormwater runoff is absorbed by soil. It is part of the natural water cycle: When it rains, storm water runoff gets absorbed by the soil and infiltrates the ground, either to percolate and recharge the aquifers beneath it, or to travel laterally toward rivers in a motion that’s called interflow.

But in the city, where there is hardly any soil, the natural water cycle is disrupted.

When rain touches any kind of surface, it is called storm water runoff. Storm water runoff that does not go through infiltration — that isn’t absorbed by soil — is called surface runoff, otherwise known as baha. When everything is covered with concrete, the surface runoff increases.

In the natural water cycle, surface runoff only makes up 10% of the total rain, with 50% going into infiltration, and 40% into evaporation.

But because of urban development, the figures have changed. “Instead of the normal 10%, surface runoff has become 50%,” Redillas said.

What this disruption has done is short-circuit the natural water cycle. And short-circuiting the natural cycle can lead to many more and graver problems — among them contributing to sea level rise and a worsening flood situation.

Redillas says going back to the natural way of things is next to impossible, especially in the city, where concrete has all but replaced soil. Fortunately, something can still be done.

The BGC Greenway is an example of unused spaces turned into a park.

Alcazaren said repurposing old infrastructure is a possible solution to meet the rising need of green spaces in Metro Manila. “The cemeteries can be reconfigured as parks if we can improve infrastructure, to allow people to use them, and not just informal settlers living between the tombs,” Alcazaren said.

There are also old unused spaces that can be turned into parks, not unlike New York City’s High Line, an old abandoned rail trail that already had vegetation growing. “We’re already doing that,” Alcazaren said, pointing to the BGC Greenway. “It’s the old Meralco easement, between Manila Golf and the condos, that was unused. We turned it into a 2km green jogging path, although the masterplan was closer to 4km,” he said.

Alcazaren added it was possible to still make it better, but alas, “it wasn’t a priority.”

Lining the streets with trees is also possible, but that takes more work than it looks. “It’s not as simple as digging a hole, planting a tree, and hoping for it to grow,” Alcazaren said, as he recalled how his firm greenified the Makati Central Business in the last 20 years.

“I had to explain that all the trees, we had to dig the tree pit and replace soil. We chose native trees and it’s now doing very well,” he said proudly.

Redillas agrees. “When you plant a tree, it still has needs, for instance you’ll need to water it,” she starts, saying a program of street trees will fare much better and be more efficient if we lean on low impact development (LID) and nature-based solutions.

LID brings together engineering practices and natural elements to make cities safer for people and friendlier to the environment. Instead of requiring massive space like parks, what LID needs is something that Metro Manila could still be able to provide: depth.

Low impact development and nature-based solutions could be a key in preventing many issues plaguing the urban environment.

“The good thing about nature-based solutions and LID, you don’t really need that much space,” said Redillas, who finished her doctorate studies on nature-based solutions, low impact development, and storm water management in Korea.

Instead of looking for space to build parks and bring back soil, Redillas suggests building nature-based solutions like rain gardens and bioswales: landscaped depressions that features plants and trees, design to hold surface runoff.

In cities, Redillas said, infiltration should be the top priority, with so much of the ground having been paved. For instance, in a parking lot, rainwater is usually directed straight into the pipes and down the drains. “If instead you build a bioswale there, that can hold surface runoff instead of it going straight to the pipes,” Redillas said.

That means the runoff would be held in the bioswale first, slowing down the flow of water. “We can provide detention, and then retention, tapos filtration. We can put filters there before infiltration takes place so that the water doesn’t just stay on the surface. That way, we could really reduce flooding,” Redillas said.

In planting street trees, meanwhile, LID will involve planting these on box filters with holes in the ground. Those holes will allow surface runoff to enter, which then can be used to water the tree, or even be treated before it’s led down to the pipes that are connected to the drainage system.

These tree box filters can not only help in managing flood during the rainy season, they can also help in managing what experts call the first flush phenomenon, the dark floodwaters which is the result of the first 30 minutes of rain bringing in all the pollution and sediments that have accumulated on the ground during dry days.

In Metro Manila, Redillas imagines building LID parkways by the highways, innocent-looking carpets of green punctuated by trees. These can mitigate heat island effect, help bring back infiltration in the city, treat runoff water from its first flush, and with filter strips by the side, help mitigate flood. This way, the city is able to get back some of the greens it’s lost. And while applying nature-based solutions and LID to Metro Manila isn’t enough, it’s a good start.

“These are micro efforts that we build where the problem is,” she said.

For Alcazaren, green remains key. “Government really needs to shift away from gray infrastructure that’s all concrete to green infrastructure that embeds urban design and landscape architecture into the picture,” he said.

The Stand For Truth documentary 'saving bees, saving cities' highlights the need for more green spaces in ncr.

There are some reasons for hope. Alcazaren reports a better “consciousness from developers about the importance of green spaces.”

“Previously, developers didn’t prioritize green open spaces because it’s lost income,” he said. “But now, there is more consciousness for these spaces and a number of developers are using this to push their properties. There are parks, proximity to these is given more weight than previously.”

But it still remains an uphill climb when talking to other stakeholders, in particular, those from the government.

Recalling his experience with the Iloilo Esplanade, the urban planner said people in government are still very car-oriented. It took a while for officials “to understand how to design for people rather than for cars.”

“Their metric is still car-oriented,” Alcazaren said. “It’s all road-widening projects. It’s not sidewalks, it’s not connectivity. It’s still car-centric. That’s the problem.”

And then of course, there’s the valid concern about money, “because it’s not free,” he said. Building parks has its costs, maintaining them brings with it another set of new ones. The common thinking, of course, is how to at least recover these costs.

But for Alcazaren, those in charge could not afford to think that way. “You can’t make a park a profit center. You don’t have any direct value capture or profit generation,” he said. “It’s the quality of life provided for the people — that’s the investment.”

The pandemic has already shown that green open spaces aren’t just nice things to have. And with the effects of climate change already knocking at our door, it is about time the government finally makes the investment and the commitment to not just raise the quality of life in the city but to protect it.

The hope, Alcazaren said, “is to knock some sense in government to convert the remaining spaces into parks for our survival. That means do not sell off any more properties like Camp Aguinaldo and Camp Crame. Do not sell off the National Center for Mental Health. Do not sell off the rest of BGC. Stop selling. Stop reclaiming.”

Only then can we start making these available spaces work to turn Metro Manila more humane and suitable for human life.

In-depth special reports and features showcasing the best multimedia storytelling from GMA Integrated News.