We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

Names have been changed to protect the identities of the survivors. Details in this story may trigger survivors of sexual abuse.

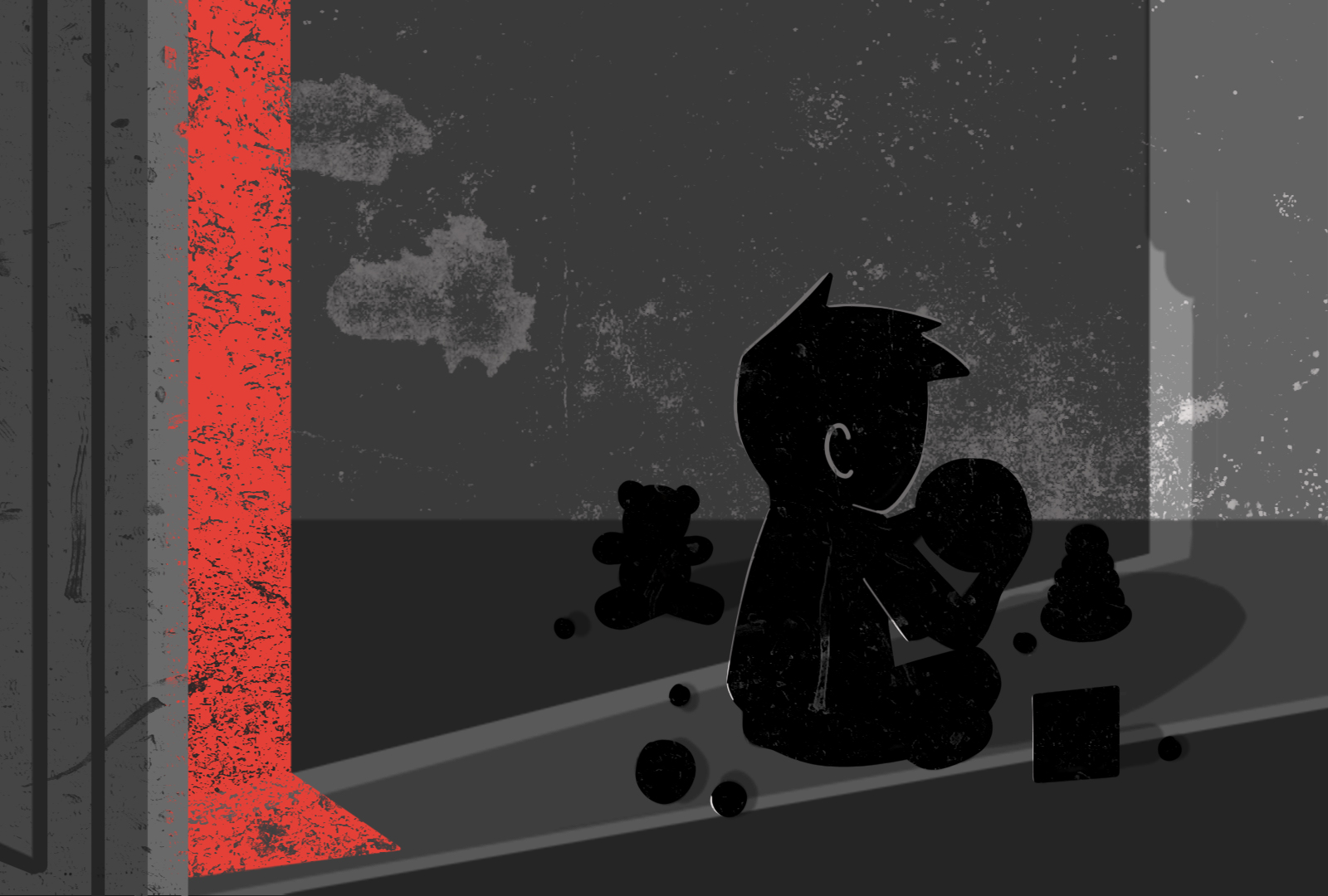

There was a secret in the family that only little Jonah knew.

After everyone else in the family would leave him alone at home to work, their front doorwould open and a man would sneak in. Jonah would hear the footsteps approaching and see the face of his father entering his sight.

“He comes back and he does it to me. He tells me I shouldn’t report it, that I shouldn’t tell it to anyone,” said Jonah, who was only eight years old when it all started.

At the beginning, Jonah thought it was normal for a father to do that to his son, but he always felt uneasy keeping his father’s secret.

“He’d tell me to not tell anyone. And I’d ask, ‘Why can’t I say it? Is this wrong?’ I was just a child and I didn’t know. But even then, there is still a feeling of discomfort and confusion because it didn’t feel normal. Why did he do it when there was no one around?” he said.

It wasn’t until second grade, during a class about the reproductive system in school, when he figured out the truth about the secret he and his father shared. But he was powerless to stop his dad, and the abuse would go on for six long years.

For Jonah, it wasn’t for lack of trying. As he grew older, he found himself trying to find ways to avoid his father at home. “When I was in high school, I didn’t stay at home anymore. I’d stay in school. I’d go home late just so I can avoid him, avoid the family. I’d leave in the morning, and I won’t be home until night.”

One day, the weight grew to be too much. Looking for anyone who could help, Jonah turned to his eldest brother, revealing the secret.

But instead of offering support, his brother lashed out at Jonah, saying the revelation could destroy the family.

“He told me not to report it, because if I did report what was happening at home, he’d kill me,” Jonah said. “That’s what my brother told me because it turned out our father did it to him too.”

It was a shock for Jonah to find out that the secret wasn’t his alone.

According to the 2016 National Baseline Study on Violence Against Children in the Philippines, many more young boys share the same plight.

The study found that more male children have experienced sexual violence compared to female children.

According to the study, 3.2 percent of children and youth experienced forced consummated sex during childhood, with a higher prevalence for boys (4.1 percent) compared to girls (2.3 percent). In the school setting, the prevalence among boys (2.1 percent) was nearly double that of girls (1.1 percent).

While more girls reported more forced consummated sex at home, more boys reported having experienced unwanted touching, and sex videos and photos taken without their consent.

Despite this, much fewer male sexual abuse survivors sought help from children protection units. In a 2018 study by the Child Protection Network, 6,569 girl survivors asked for help, compared to just 289 boys.

Male child sexual abuse in the country has become a highly underreported issue. “[W]hile sexual victimization in general is underreported, the sexual violence among boys are even more underreported,” the study said.

“There is this notion that boys cannot be raped. It’s like people make fun of you if you cry rape,” said Zeny Rosales, executive director of the Center for the Prevention & Treatment of Child Sexual Abuse (CPTCSA).

“Our stereotype and expectation is that men are strong, men are macho, men can’t just be abused because they’re men. That’s why there’s a big difference in how we raise them.”

have reported experiencing forced consummated sex

have reported forced consummated sex, compared to 2.3 percent of girls

have reported forced consummated sex in school, compared to 1.1 percent of girls

This became clear for Jonah when he tried to seek help outside home.

“I explained to the guidance counselor, but they didn’t do anything. They just counseled me. I even felt humiliated because after I shared my story with the guidance counselor, I became the talk of the school,” Jonah said.

The comments led to even more confusion for Jonah. “They’d tell me that since I was able to know what sex tasted like, I was a real man,” he said.

Being stoic, being strong, controlling your feelings — all these come with being a man in the Philippine society. Boys are also expected to “enjoy” any form of sexual encounter even if it was forced.

“And if you tell your friends, they’d tease you,” Rosales said. “‘What’s wrong with you? At least you were able to experience it since we haven’t.’ It’s those information and reactions that give these survivors confusion. Some would even tell him that he’s complaining when he already had free sex education.”

Sexual arousal during the encounter is also common, which could lead to even more confusion for young male survivors, according to Dr. Ronald del Castillo, a former associate professor at the University of the Philippines Manila College of Public Health

“It plays into the fear, the same, the embarrassment and guilt because if I liked it that must mean I must have participated or I allowed it to happen,” he said.

Because of the different standards, communities are failing to identify boys as victims of sexual violence. Aside from these expectations, boy survivors also have to face the fear of retaliation from their perpetrators.

According to the 2016 study, the most commonly cited perpetrators of sexual violence among boys were cousins, fathers, and brothers, just like Jonah’s.

More often than not, Rosales said, perpetrators of male child sexual abuse are men. CPTCSA, which has handled cases of boy survivors as young as five years old, said that away from home, someone in authority could perpetrate the sexual violence.

“I think there's a very real fear for some survivors, fear of retaliation,” Del Castillo said. “So there's a fear of retaliation that if I disclose to someone else that they will hurt me and that’s very real and an understandable reason why one would not disclose that experience of abuse.”

There is also the fear for the survivor of being doubted or worse being ostracized for reporting his experience. And then there is the matter of what would happen next.

“If I did ask for help, who would pay for it? Like these kinds of things that I think are real concerns even if I was ready and willing to disclose something so secretive and vulnerable,” Del Castillo said.

“Our stereotype and expectation is that men are strong, men are macho, men can’t just be abused because they’re men. That’s why there’s a big difference in how we raise them.”

At the age of 14, Jonah ran away and lived on the streets.

“I thought I was going to be free,” he said.

But he only found himself jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire. He was taken in by a drug syndicate, who forced him to go into prostitution.

“Sometimes, there were couples,” he said. “They were different types. Straight man, straight woman, gay, husband and wife, it really varies, but most were gay.”

Jonah remembers his best friend, another street youth, who was tortured and had his eyeball cut out to scare the other kids against trying to escape.

Through it all, Jonah held on to a dream.

“When the other street children and I would talk, I’d tell them that I still wanted to study, but they’d laugh at me and tell me that we didn’t have those chances. I didn’t believe that. I tried to find my way,” he said.

When one of the street youth would get sexually transmitted infections, Jonah would be the one to bring them to social hygiene clinics. Whenever he did, he’d find a way to visit different schools.

“They didn’t accept me. The last school I went to was West Visayas State University. I passed the exam and got an interview there,” he said.

His interview with the teacher was serendipitous. “She made me choose among a set of quotes and interpret it,” Jonah said, his voice breaking at the memory.

His chosen quote read: “Behind the clouds, the sun still shines.”

Jonah ended up telling the teacher about his life, and pretty soon, both of them were in tears.

Soon, he received word that he passed at the university. Although he felt paranoid about the possibility of syndicate leaders finding him, he finally felt safe and protected inside the school.

He changed his name, his looks, his lifestyle, his whole identity so the syndicate couldn’t find him. The university gave him refuge, offering him free lodging for seven years.

Although he felt paranoid about the possibility of syndicate leaders finding him, he felt safe and protected inside the school. Later, he would get scholarships and jobs, from fastfood chains to government agencies as a youth leader.

It took him six years to complete his course, originally a four-year curriculum, because of all his side jobs.

Jonah was able to make the most of his time in college, when he founded a non-profit organization dedicated to support male child sexual abuse survivors and stop the spread of HIV among street children and protect them against sexual exploitation.

Today, he has sessions with a psychiatrist, works for the DSWD, and is studying for his master’s degree in guidance and counseling.

At 11 years old, Noah was smaller and younger compared to the rest of his high school classmates. With his naturally effeminate nature, he was often picked on by the people around him.

But while he was used to being the butt of jokes, the prank he experienced that afternoon was different. He didn’t completely understand what was happe

“It was dismissal time... I was cleaning the classroom alone and fixing the chairs when my classmate humped against me,” Noah said. “It was like he was pushing his thing against me.”

The incident was a blur, but Noah vividly remembers his classmate’s open-mouthed laughter.

“I froze. I could hear him laughing, but I couldn’t turn around to look at him,” he recalled. After what happened, Noah bolted for the door.

He tried to forget the incident, but another cruel prank would be even worse.

In class, a different classmate grabbed his hand and placed it on his penis.

“Ideally, in such situations, I should be able to scream, but I couldn’t do it. That time, I felt so small,” Noah said.

In his head, Noah thought the two incidents could not be unrelated. He suspected that both perpetrators talked to each other about what they did to him.

“You know, it was like they were aware of what they were doing. It seemed like I could see them laughing at me whenever my back was turned. As if they’re aware — you know, I think they told each other what they did to me,” he said.

It took several years for Noah to fully understand that what his classmates did to him wasn’t just a “bad joke.” It was sexual harassment.

“At that time, I thought maybe he was just bullying me. But that kind of thing, it’s really confusing to me because I don’t know why he did that,” he said. “But, you know, I realized later that I wasn’t just bullied, I was harassed.”

The realization came when he was in his sociology class, four years after the initial incident. His teacher was discussing sexuality and gender, and as the words “consent” floated in the air, Noah remembered shaking in his seat. “It was like it confirmed to me that, yes, it was like that.”

“If our parents are not used to [talking about sex] and they are not trained, who will teach the children when parents themselves feel discomfort?”

Because he was confused, Noah never thought of filing a case against his harassers. It took him years to open up to his friends. Until today, he has neither told his family nor any figure of authority.

“I know that’s what usually happens to victims at first, they think that it’s nothing. That’s how I reacted,” Noah said.

“Since I was in high school, I didn’t know much, so I really didn’t know who to turn to and how to address it. I just really shoved it.”

It is a natural reaction for many young male victims of sexual abuse, said Zeny Rosales, the CPTCSA executive director.

“Will they laugh at me? Second, sexual abuse against male child victims is really not normally discussed. Third, is this sex education? Some of these have no explanation. And these are the questions they usually ask,” she said.

Complicating efforts for schools is the opposition of groups, including the Church, against teaching proper sex education. Many parents are also unequipped to provide the proper guidance.

“If our parents are not used to [talking about sex] and they are not trained, who will teach the children when parents themselves feel discomfort?” Rosales said.

There is also a fear among parents and adults in authority that the subject is not a proper matter for children. “They feel like the children are going to be taught obscene things," Rosales said.

“What they don’t know is that children are already aware and that’s why they’re asking the adults,” she added.

Many male abuse victims also become confused about their sexual orientation and identity, especially if the perpetrator is male.

“If my sexual partner is male, who between us is homosexual? Is one of us homosexual? Is it him or me? And if I’m not homosexual and he is, would it affect me?” Rosales said, talking about the questions that go through the minds of victims. “That’s why one of the issues is they question their identity. They ask is being gay contagious, is being gay a sin?”

These are some of the questions, she said, that could be answered with clear sex education.

Because we live in a predominantly heterosexual world, of which many parts still frown upon same-sex activities, male victims of child abuse may feel “shame, guilt, embarrassment” for participating in an activity, even if it was forced.

Dr. Ronald del Castillo, the public health expert, said the sexual orientation of victims is not linked to the orientations of their abusers. “So whether the perpetrator is male, female, is not linked to our sexual orientations as individuals,” he said.

For Noah, the effects of the sexual abuse he experienced as a child have been far-reaching. For one, the harassment took a toll on his relationship with his brother and his father. They were never close to begin with but after the incident, he never showed affection through touch with his father again.

“Ever since then I was never touchy with my father. I was never touchy with my brother but as much as possible, I didn’t go near them anymore after the harassment.”

It has also affected him beyond the home. “I don’t make friends with any straight guys,” he said. “Whenever I go out, I have this feeling that they're out there to bully you or violate you.”

His reluctance to interact with straight men, in fact, led him to quit his job as a writer at an online publication. He said his editor reminded him of his harassers.

“I’m not saying that he did something. But the fact that he’s a straight guy reminds me of the people that harassed me before. I couldn’t handle it so I left my job,” Noah said. “Even though he was so kind, I couldn’t bring myself to work with him because he was a straight guy.”

For some victims, the effects of such sexual abuse doesn’t just affect a way of their life. Some end up losing a big part of themselves.

Everything was normal for 16-year-old Peter when he left his house, bid his mom goodbye, and went to his friend’s birthday party last year. When he came back, he was a different boy.

“We noticed that he was acting differently, as if he was going crazy,” Peter’s mom said.

There was drinking at the party, and once the kids had gotten drunk, the perpetrators stripped off their clothing and touched the victims’ private parts.

The memory of what happened to Peter in the aftermath of his abuse still remains vivid when his mother tells the story.

“Sometimes his eyes would roll into the back of his head, as if he was afraid of something. Sometimes he would cry, sing. Sometimes, he would suddenly be afraid,” she said.

Peter would end up being admitted to a mental hospital, where his mother — the only one allowed to go with him because of quarantine protocols — saw him against his binds while breaking down in tears.

“He was screaming, crying,” she said. “It was painful.”

But although his case is extreme, he is far from alone in carrying the effects of the abuse done to him.

According to Dr. Ronald del Castillo, trauma-related symptoms are “very common” after the abuse. “Anxiety, flashbacks, hyper-vigilance, tension in the body. To some people, they experience low mood, sadness, and loneliness. In worse cases, depression, self-harm, even suicide. And not just harm to self but also harm to others,” he said.

Some victims also experience physical manifestations like headaches, backaches, and tensions in the body. In the long term, survivors of abuse may even have difficulties with their own personal and intimate relationships and friendships.

“It can be difficult to have longterm relationships because longterm relationships require a great deal of trust and vulnerability,” Del Castillo said. “And so for people who have a history of abuse, especially chronic abuse, the trust is difficult to establish to begin with, with anyone, because that trust was broken or the idea of that trust was broken.”

“It’s hard when it’s a male who says that he’s also vulnerable, that he also needs help, intervention.”

Complicating matters is the lack of a support system for male victims. Organizations dedicated to the prevention and treatment of child sexual abuse like the CPTCSA have a difficult time for adult men who still suffer the effects of trauma they experienced as children.

“If a male person called us and said they are depressed and asked us where they could go, what would I refer to him? He’s not VAWC [Violence Against Women and Children] because he doesn’t meet the category, right?” said Zeny Rosales, the CPTCSA executive director. “It’s hard when it’s a male who says that he’s also vulnerable, that he also needs help, intervention.”

There is also a lack of research related to abuse experienced by boys. “We don’t have data. This is why this campaign is difficult, because it’s not backed up by reported cases,” Rosales said.

Five years after 2016 National Baseline Study, there has yet to be another nationwide effort to show the data on male child sexual abuse.

Currently, survivors referred to the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) for temporary protective custody are brought to 32 centers across the country depending on their age. However, the agency acknowledged that referral systems need to be improved.

“There is little help-seeking behavior from the victims, low awareness and low utilization of existing and available child protection services from their community, LGU (local government units), and national government agencies,” the department said.

The DSWD said referral systems still need to be improved to include gender-sensitive barangay authorities to receive reports on sexual abuse among boys. Currently, the Committee on the Special Protection of Children (CSPC) Protocol designates women in the VAWC Desks. “There is also the need to install the same mechanism in schools where sexual exploitation and abuse among boys usually happen.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has also taken a toll on these efforts, with both boy and girl victims encountering difficulties in reporting because of the mobility restriction brought by the quarantine. The pandemic, the agency said, has increased the risk of children suffering from abuse and exploitation while in their homes.

The DSWD said that they’ve opened helplines, adopted an “enhanced referral mechanism” where barangay authorities are given the primary task of taking in child abuse reports and immediately reporting these to the Local Social Welfare Development Office (LSWDO) in their area for appropriate intervention as may be necessary.

“If we have anger in our hearts and it will be what governs us, there’s a high chance that we will repeat this same violence to the next generation.”

For Jonah, the child sexual abuse survivor who now counsels other victims, interventions currently given by government and NGOs are often superficial.

“It doesn’t really address the deep wounds, the worth, self-worth. Because this is what was taken from them. If you are a child and you are a victim of sexual abuse and exploitation, this is what was taken from you, your dignity. So we have to return that, the dignity that was robbed from us,” he said.

Without guidance, victims of abuse may develop internal or external aggression, hurting themselves or the people around them. Many of those who experienced exploitation become aggressive: they harm their perpetrators, and even other people.

Jonah said it was important to break the “generational cycle” so victims would not end up becoming abusers themselves.

“What’s important is for victims to become survivors, to become peacemakers. Because if we have anger in our hearts and it will be what governs us, there’s a high chance that we will repeat this same violence to the next generation,” Jonah said.

Meanwhile, boys who have suffered abuse are left to deal with the pain. Peter, who suffered the breakdown after experiencing abuse at the party, has been getting better, taking his medicine everyday.

But the damage has not been limited to just him, or his mother who had to witness him struggle at the mental hospital. The whole family also suffered, after the perpetrators of the abuse shifted the blame to them on social media, after news of the incident became public.

Aside from her son’s recovery, Peter’s mother is also hoping that justice would find his abusers one day.

“You know, I really want them to pay for what they did,” she said.

Peter was not the only boy who was invited to the birthday party that left him haunted. Jason was there too, but the nightmare he experienced started long before the night of the party.

It only became clear to his parents after a sudden visit from Peter’s family.

“My son was only 14 years old at the time and he was not yet aware of what he was doing,” Jason’s mother said.

The abuser would give Jason an allowance every week, making sure the boy knew just how much nicer he was compared to others.

“It was like they groomed my son,” Jason’s mother said.

The shocking realization came: the person who had been abusing Jason was someone close to her.

“Us mothers, we take care of our children, love them to the point that we won’t even allow a single fly to touch our children, or a sweat to drop from our children. And that’s what they would do to my child?” she cried.

His family has filed charges against the perpetrators, but the wheels of justice turn slowly.

Child protection expert Cristina Sevilla said that families of male child sexual abuse victims had a more difficult time because of the way laws were made.

She cited as an example Article 337 of the Revised Penal Code.

Qualified seduction. — The seduction of a virgin over twelve years and under eighteen years of age, committed by any person in public authority, priest, home-servant, domestic, guardian, teacher, or any person who, in any capacity, shall be entrusted with the education or custody of the woman seduced, shall be punished by prision correccional in its minimum and medium periods.

“Now what’s the problem with that? It assumes that during childhood, only females can be groomed,” Sevilla said. “So aside from that law only protecting girls or women, and disregarding the fact that there are boys that are subjected or groomed for sexual activity, this law also really perpetuates the idea that when we talk of innocence especially childhood innocence or purity, we're just talking about girls.

“We're just protective of girls, in effect, disregarding the plight of boys.”

For Sevilla, this also has the effect of normalizing discrimination against sexually abused boys, and perpetuates the thinking that boys do not need protection.

“Rape should be rape whether you are a man or woman, whether you are a boy or a girl and that there should be no distinction with respect to the penalty. There should be equal treatment,” Sevilla said.

Another example is Republic Act 8353, also known as the Anti-Rape Law of 1997.

Under Article 266-A, rape is classified into two forms: one is “by a man who shall have carnal knowledge of a woman” through force, threat, and intimidation, while the second is “by any person who, under any of the circumstances mentioned in paragraph 1 hereof, shall commit an act of sexual assault by inserting his penis into another person’s mouth or anal orifice, or any instrument or object, into the genital or anal orifice of another person.”

The two crimes have different punishments.

“If it’s vaginal rape through vaginal penetration, that’s reclusion perpetua, which means it’s not bailable, [it’s] 20 years and only to 40 years, but the rape by sexual assault, that’s only six years and one day to 12 years,” she said.

“These laws,” she added, “set the standard on how we view boys vis-a-vis girls, and how we protect girls vis-a-vis the boys.”

If the law discriminated against boys, it may lead to more victims due to less protection because they are more vulnerable. Because of this, Sevilla urged the administration and the authorities to fix the current legislation on sexual violence, especially against boys.

For its part, the DSWD acknowledged that “there are laws that did not recognize male children” who are victims of sexual abuse, but noted that there are pending pieces of legislation, including a bill to increase the age of statutory rape, that specifically addressed the issue.

For male victims of child sexual abuse, a long fight looms to end their silence.

For Zeny Rosales, the CPTCSA executive director, it begins with how we raise young boys.

“You have to allow men to express their emotions,” she said. “It’s very ingrained in our culture. We don’t teach it to our children... but they absorb it immediately because it’s what they’ve been used to. When they are born, it’s what they hear from us.”

There needs to be changes too with how society views boys, which is key to being able to protect them. Child protection expert Cristina Sevilla said there needs to be public discussions about how boys can also go through victimization.

“We have to get rid of these stereotypes on how boys should act, how they should be perceived, and that we should remove this idea that victimization is associated to the victim being weak or having done something,” she said.

Dr. Ronald del Castillo added that it’s important for survivors to know that help is available, whether in the form of therapy, a trusted friend or trusted adult to begin conversations with.

“For many people who’ve experienced sexual abuse, especially in childhood, it’s there, holding it in for so long that that secret, in a way, sort of eats at you, like it gnaws at you,” he said. “And so to be able to share that, I think to someone you trust, even just one person to start with, I think it’s an important road to recovery.”

It takes a lot of work, but support systems help survivors “carry the weight” and feel less alone.

“I think the feelings of shame and guilt and anger and loneliness are common. They’re very common. But they don’t have to be forever,” De Castillo said.

For Jonah, who suffered abuse at home at the hands of his own father, it took years of work to reveal his secret. But secrets like his don’t have to be kept in the dark forever. And finally finding his voice has allowed him to help others find theirs.

The organization he founded, Kabataang Gabay Sa Positibong Pamumuhay, has served over 8,000 youths and was recognized twice by the Ten Accomplished Youth Organizations (TAYO) Awards in 2003 and 2006.

His project River of Life Initiative (ROLi), an HIV risk reduction program that uses self-assessment toolkits, workshops, and peer group work to help young men who have sex with men assess and reduce their risk behaviours, was recognized as a case study of good practice by the World Health Organization in 2017.

He has hardly looked back. After he ran away from home, he has only gone back once to the house he left: when his perpetrator was on his deathbed.

“My dad in 2016 wouldn’t sign his last will and testament if I didn’t go back and visit him. He was bedridden. I said that I didn’t want to go, let them all die there. But my aunt called me and said that I should at least show myself because he was going to die within a week,” Jonah said.

“So I went back. I saw the machine that was keeping him alive... he couldn’t speak but he was crying.”

Jonah never returned after that. Although he’s detached himself from his siblings and mother; he says they are toxic for him. Still, he hopes someday they could be reunited.

“That’s my last goal in life,” Jonah said.

Jonah said he has learned to forgive himself after believing, for so many years, the abuse was his fault.

“There are so many little boys who are sexually abused and exploited and are being blamed for their own victimization,” he said.

“It’s not your fault.”