June 27, 2021

The house occupied by the Aquino family during their exile in Massachusetts. Photo: Jun Veneracion

Before Noynoy, there was his father Ninoy, the man with the limp who opened the door to let in a callow college sophomore into his sparse university office in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

I was then 19 years old, working on a research paper on the United States military bases in the Philippines. I knew no one else in the Boston area who had any first-hand knowledge of the topic. A former senator, Ninoy Aquino then was a little-known exile in America, permitted to leave political prison in the Philippines for heart surgery and recently arrived in Boston to take up a fellowship at Harvard. It was 1981.

I had seen him give a talk in a school auditorium a few weeks earlier in the dead of winter. There were only about two dozen people in the audience, including a few homeless who were there only because the space was heated, but he sounded like he was addressing a miting de avance. His passion filled the room.

Desperate to finish my paper, I gave his office a call. He picked up the phone himself and instead of just answering my queries, he told me to come to his office. He even called me, “Pare.”

He occupied a small office he shared with an African scholar who wasn’t there. There was nothing on the walls and not even family pictures on his desk; he had apparently just moved in.

I stayed much longer than I expected, listening to him not only talk about the US bases (he was a bit careful not to offend his hosts) but share gossip about Filipino politicians and their children, and his prognosis for the country’s near future. He talked about what he knew of then-President Marcos’s illness, and the “bloody merry-go-round” of power if Marcos were to suddenly die. As for the limp, he told me he had a fall during a speaking trip to another state.

The wide-eyed student just trying to write a paper left his office more than a bit overwhelmed. It wasn’t just the knowledge or insight that I got, but the time and attention. He spoke to me like a peer and looked at me in the eyes. I was still too young to realize that it was an aptitude shared by many skilled politicians.

As different as we were, I came away with the feeling that we were alike in at least one way – we were both homesick Filipinos who loved the company of other Filipinos, especially in a place where there were so few of us.

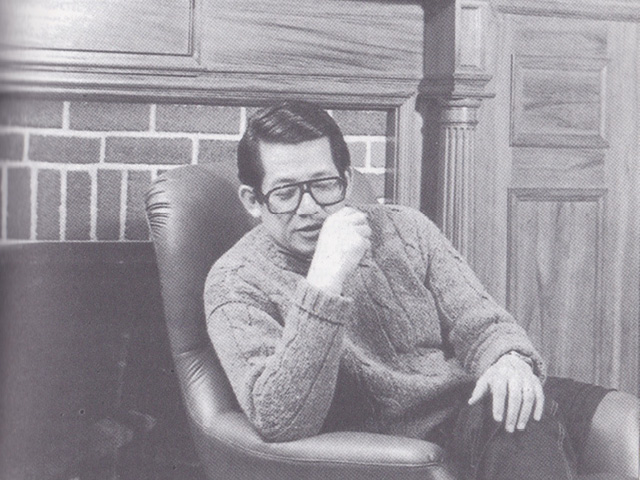

Late senator Benigno Aquino Jr. in Massachusetts. Photo: Benigno S. Aquino Jr. Foundation

I would seek out his company again, this time in a small academic seminar where we were the only Filipinos in the room. He made the Americans gasp when he mentioned that the influential Cardinal Sin had to be more like Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, whose followers had just taken over the US Embassy in Tehran and taken everyone in the embassy hostage. But what he meant was the church leader needed to be more active in opposing the dictatorship.

Soon after, he would return home and become a martyr. He was also the first person I knew as an adult who died.

Like other overseas Filipinos during this time, I went home to join the ferment that would eventually lead to people power and political change in 1986.

Thirty years after the death of Ninoy, and accompanied by my documentary team, I would return to the city where we met and visit his former office in a squat colonial building where he welcomed a young Filipino stranger like a friend. A portrait of a smiling Ninoy now hangs in a conference room in the building.

This time, in 2013, his son Noynoy was already president.

In 2013, Howie Severino produced an I-Witness documentary on the Aquino years in Boston.

I was surprised to recall then that I had never asked Ninoy about his family.

But he did have a family life in Boston, the private and happy flip side of the public, intense Ninoy. Those were the three years in the early 80s when all five kids and the two parents lived together for the first time since the youngest, Kris, was a baby. Noynoy was the only son and the middle child.

They lived in a modest brick house across from the campus of Boston College and along the route of the famed Boston Marathon. When I paid the house a visit, the unmarried elderly sisters who now own the house and lived there showed me Ninoy’s sunlit study on the ground floor where he’d do his writing and every year watch the marathoners run past his window. That was his simple man cave where he could have made the fateful decision to return home.

There was no marker or any other sign in the house that two future Philippine presidents had once lived there.

Ninoy wasn’t the handyman in the house, according to his eldest child Ballsy Aquino Cruz whom I interviewed, partly because he had had recent heart surgery. It was their mom Cory who took charge of minor repairs and household emergencies like a flooded basement from a water leak.

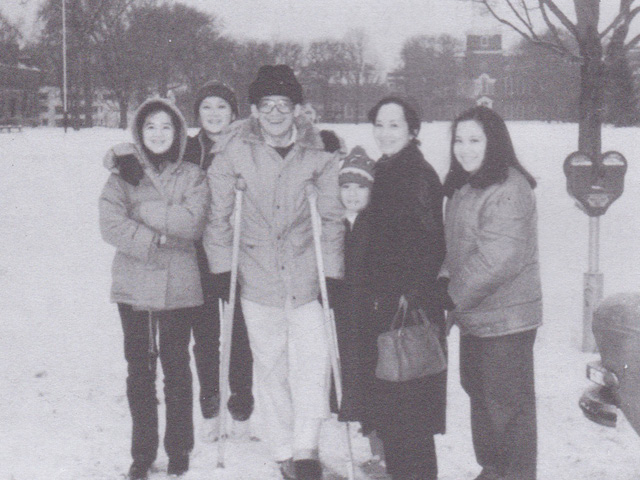

The Aquino family in Massachusetts. Conspicuously missing is Noynoy Aquino, who remained in the Philippines to finish his studies at Ateneo de Manila University. Photo: Ninoy and Cory Aquino Foundation

Noynoy himself declined our request for an interview about those years, but Kris eagerly obliged and described the joy of being the constant object of her father’s attention, recalling that he never missed a school event or play even if Kris had only a minor role.

She also said those years were financially tight for the family. “Alam na alam ko what it’s like na magtipid sa kuryente,” Kris recalled. “Like now super conscious ako na ‘hoy magpatay kayo ng ilaw’ or pag walang tao, ‘patayin n’yo yung aircon,’ because of those years.” (“I know what it’s like to conserve electricity… Now I’m super conscious and tell others, ‘hey, turn off the lights,’ or if no one’s in the room, ‘turn off the aircon,’ because of those years.”)

His sisters told me that while the rest of the family became comfortable in America, there was one member who felt out of place during their exile, and that was Noynoy.

After his father’s heart surgery in Dallas in 1980 when the entire family was together, the 20-year-old Noynoy went back to Manila alone to finish his last year as an economics major at Ateneo de Manila University.

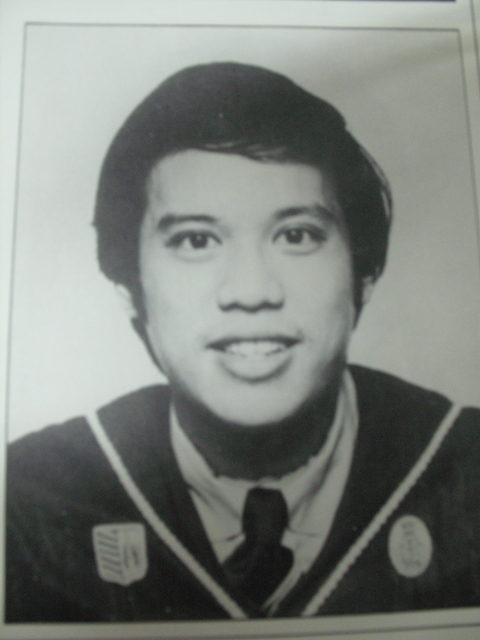

Noynoy Aquino graduated from Ateneo de Manila University in 1981. Photo: The Aegis

So as his family was adjusting to a new life in Boston as a nuclear unit again, Noynoy was living by himself until his graduation a year later, which his exiled parents couldn’t attend. When he finally rejoined his family in the US in 1981, the rest of the family had already happily settled in, his dad Ninoy with a prestigious fellowship at Harvard, 10-year-old Kris enrolled in a private Catholic school within walking distance from their home, his sister Viel in college, the two eldest sisters Ballsy and Pinky working, and mom Cory the anchor at home who kept everything humming with Ninoy’s steady stream of visitors.

“Yung aming one year of setting up house and all that, kami-kami yun, he (Noynoy) wasn’t part of that,” Ballsy the eldest said. “Yung kanyang transition, I would say, walang transition ano. Parang masyadong biglaan… Dumating siya na parang hindi pa rin niya alam kung ano ba talaga. I think maybe it was also his age, you know soon after college and then you live in exile. i think it was the most difficult for him.”

(“When we spent the first year setting up house and all that, that was just us. Noynoy wasn’t part of that. His transition was really no transition. It happened so fast. He had no idea what to expect.”)

Kris was more direct: “Hindi siya happy talaga dun, unlike me na I could've lived there (the US) forever... And I think it was really hard to be an only boy when you're surrounded by four sisters.” (“He really wasn’t happy there.”)

“Siya yung type talaga na parang hate niyang bumyahe,” Kris continued. “It’s not his thing talaga. Love niya dito. Pwede sya sa Tarlac forever. Not like me nga na parang I kept telling my mom and dad, can't we become Americans? Tapos sabi ng dad ko, you'll never be American, you're Filipino. Ginaganun ako. Sabi ko, ok fine.”

(“He always hated travelling. He loves it here. He could stay in Tarlac forever. Unlike me, I kept telling my mom and dad, can't we become Americans? Then my dad would say, you’ll never be American, you’re Filipino. He would tell me that.”)

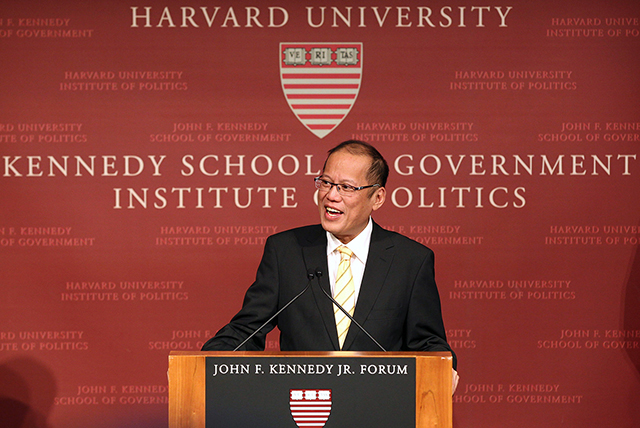

Noynoy Aquino returned to Boston in 2014... this time as President of the Philippines. Photo: Ryan Lim/Malacañang Photo Bureau

Prior to the US, Kris had no memory of her father living at home as she was a baby when he was imprisoned in 1972, released only in 1980 for surgery and exile in America. So it seemed Ninoy was making up for lost time by being a constant, doting presence. He and Kris would go to movies and bookstores, and he would show up even for PTA meetings at her school.

She doesn’t recall a similar bonding between her kuya Noynoy and her dad. When I asked if they ever did anything together, she laughed and said, “Shovel the snow. Nagsho-shovel sila. Kasi grabe mag-snow du'n.” (“They would shovel the snow. It snowed a lot there.”)

“I think Noy learned how to be on his own talaga. So I’m not saying naman that they were distant pero my dad was maybe like most dads nga talaga na may soft spot sa mga babaeng anak, dun sa girls talaga.”

(“I think Noy really learned how to be on his own. So I’m not saying that they were distant but my dad was maybe like most dads – he had a soft spot for his daughters.”)

When I was in Boston to research the Aquinos in 2013, I sought out their family friends, mostly Filipino doctors who were also Ninoy’s mahjong buddies. They had little memory of Noynoy socializing or chatting with them.

“He was the quietest person,” recalled Dr. Cherry Agular, the Aquinos’ family dentist in Boston and still a close family friend. “Every time we see him, he would just kiss, hi tita, hi tito. Tapos mawawala na.” (“Then he would disappear.”)

When Noynoy became PNoy and made a sentimental visit to Boston in 2014, he recalled the frigid winters and having to take a bath without hot water. But he also hinted at deeper personal struggles.

"I acquired the ability to adapt to a changing environment, which, as you can imagine, is very valuable when handling crises. I learned to cope with uncertainty, having had to constantly wonder when and if we could go back to our beloved homeland," he said in a speech to the Filipino community in Boston.

While Ninoy Aquino was incarcerated during Martial Law, he passed upon his son "the great responsibility" for the Aquino family.

Photo: Ninoy and Cory Aquino Foundation

Quiet, even introverted, that’s how Noynoy was described by loved ones in his youth. But even then, the brooding Noynoy, unhappy in exile, harbored a mission, assigned to him when he was just 13 by his father, then in solitary confinement in a military prison and already sensing an early death.

“You are my only son. You carry my name and the name of my father,” Ninoy wrote in a letter nearing midnight on August 25, 1973. “Forgive me for passing unto your young shoulders the great responsibility for our family. I trust you will love your mother and your sisters, and lavish them with the care and protection I would have given them… Stand by your mother as she stood beside me… There is no greater nation on earth than our Motherland, no greater people than our own. Serve them with all your heart, with all your might and with all your strength. Son, the ball is now in your hands.”

It was a letter publicly shared only after Ninoy’s death in 1983, but the words must have weighed heavily on the mind of a young man who grew up in the shadow of a political prodigy, and who was constantly underestimated from the time of his youth and even after he became president.

Noynoy must have known he was no prodigy and would forever be compared to his namesake. But his sister Ballsy believes her brother stood out in at least one way. She told me in 2013, when he was only halfway through his presidency, “I think of the five of us I would say he's the most idealistic, and especially now I can see that. You know this love of country I think comes with age and with parents like our parents kung hindi pa namin mahalin ang bayan e there is something wrong with us. Pero kay Noy, ang tindi talaga e.”

(“…With parents like our parents, if we didn’t love our country, there must be something wrong with us. But with Noy, it was really intense.”)

She thought that’s what gnawed at him in the US, even as his sisters were relishing their family life.

“Siguro lahat yun umiikot sa ulo nya – ganito na lang, dito na lang ba tayo? Hanggang kelan tayo rito? We have to go back. The struggle is there.” (“That probably didn’t leave his mind – is this it, we’re just going to live here? How long? We have to go back. The struggle is there.”)

The family did go back, the father first, only to be assassinated. That began a historic struggle that no one could have imagined.

Like millions of other Filipinos at the time, I was deeply shaken by the spectacular brazenness of his killing, frozen in time by images of a bloody tarmac tableau.

I soon found myself back in Manila a fresh college graduate, shaming myself into abandoning a careerist ambition overseas to become a teacher, writer, and protest photographer at home.

Former president Corazon Aquino (center, holding megaphone) is accompanied by her son Noynoy at an event in February 1986, days before the People Power Revolution that toppled the Marcos dictatorship. Photo: Howie Severino / Colorized by Jeric Benitez

Five years after I nervously entered Ninoy’s office with a list of research questions, I saw his son for the first time. In the tense days after the snap election in February 1986, I was taking pictures of volunteers guarding ballots in the old Makati City Hall when the presidential candidate and eventual winner Cory Aquino arrived and appeared on a balcony to boost the morale of the crowd.

Handing her a megaphone to speak to the throng was someone who looked like Ninoy, the 26-year-old only son Noynoy with a full head of hair. He was standing beside his mother, just as his father told him to do 13 years earlier.

In-depth special reports and features showcasing the best multimedia storytelling from GMA Integrated News.