We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

By ROSEM MORTON

April 19, 2021

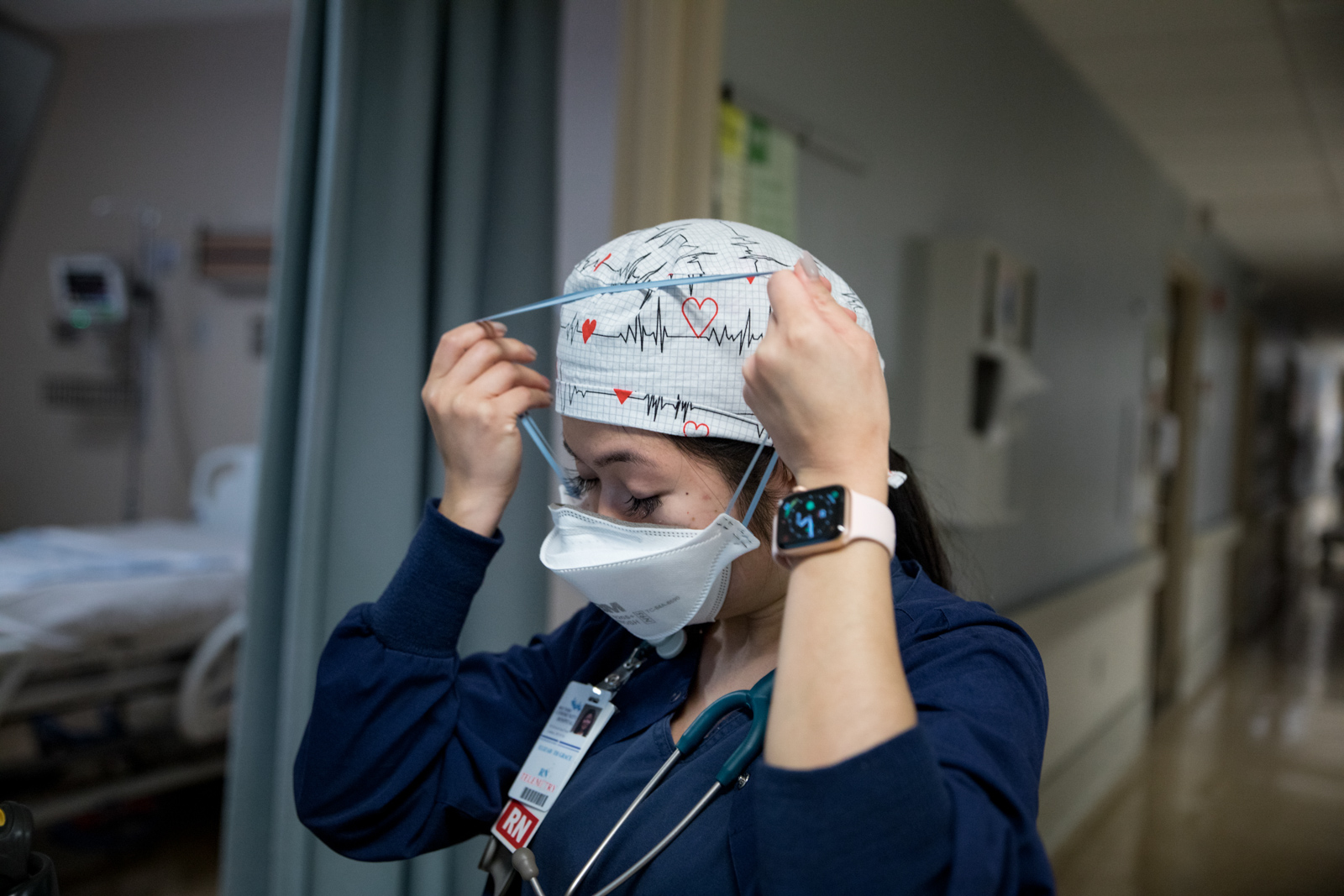

The author coming in for a 12-hour duty at a Maryland hospital where she worked in the COVID-19 ward.

Over a year ago, I found myself in a unique position: I was both a nurse and a photojournalist on the frontlines of a global pandemic.

At the hospital where I worked, we were forced to balance patient care with supply shortages, rationing of personal protective equipment, and constantly evolving policies and procedures. As a freelance photojournalist, I recognized I was one of the few people with the proper training and access to important stories unfolding around me. I began photographing COVID-19 stories, not aware that this duality of COVID-19 nursing and photojournalism would become my normal for the next 13 months.

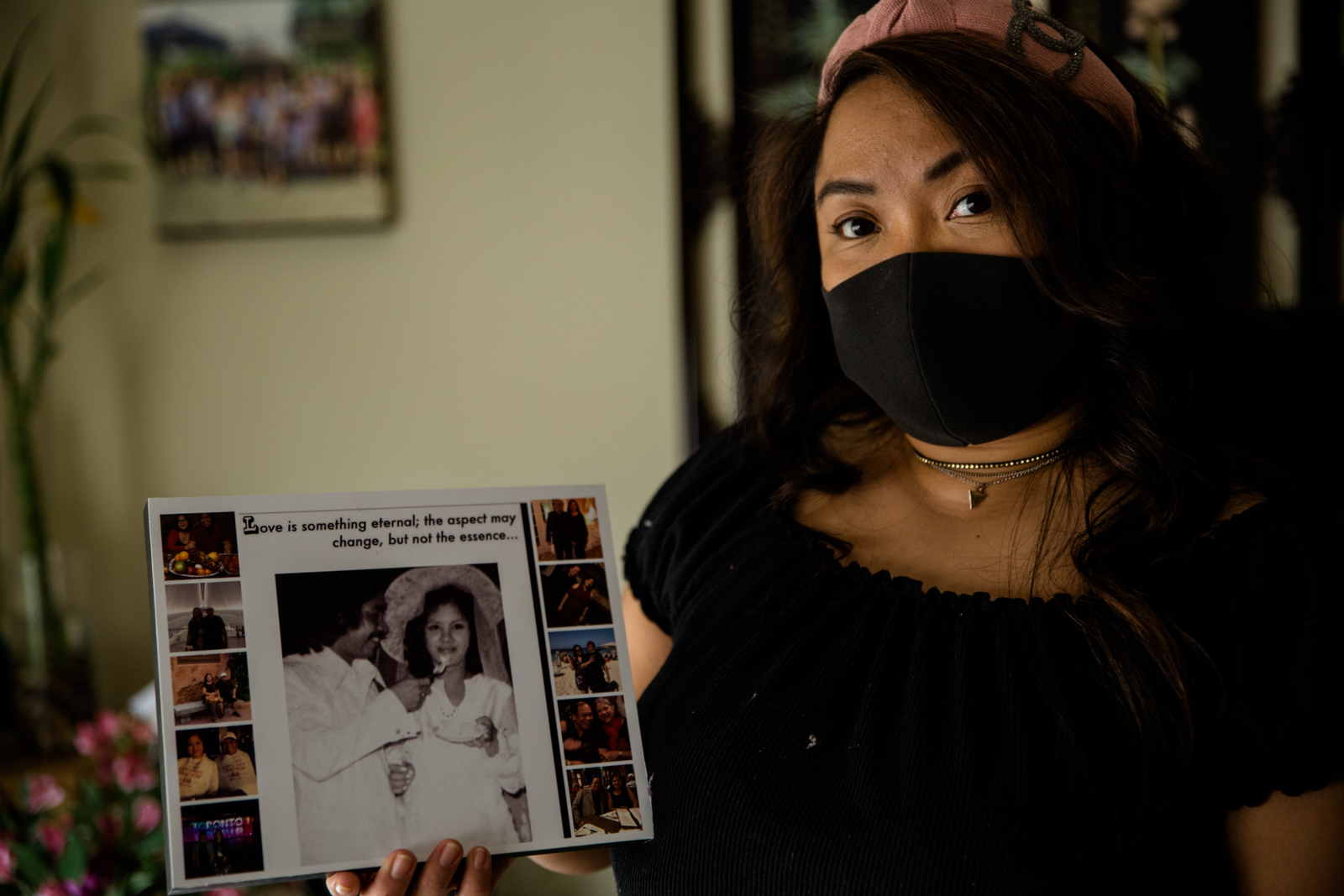

Sheryl Pabatao remembers her parents, Alfredo and Susana, who she lost to COVID-19. "It's like losing a part of your body and having to learn how to live without it," she said.

The white marble urn holding the remains of Alfredo and Susana Pabatao. Their funeral was put on hold, as the COVID-19 pandemic surged in the US.

One of the earliest stories I was asked to photograph was on the disproportionate death rates of Filipino health workers in New York and in New Jersey.

I met Sheryl and Sybil Pabatao, who lost both of their parents, Alfredo and Susana, to COVID-19. On a table in their living room was a white marble urn, containing Alfredo and Susana’s combined ashes. Alfredo and Susana’s funeral had been long on hold as the onslaught of the pandemic continued.

My heart broke as I sat with Sheryl. She recalled fond memories over the years and the days leading up to her tragic loss. “It's like losing a part of your body and having to learn how to live without it. I am learning to live without my right arm and my right leg. It is really tough,” said Sheryl as she lit candles on her parents’ altar.

Seeing Sheryl navigate through grief and use her experience to educate on pandemic safety was powerful. I came home raw and utterly changed. As I connected the Pabatao’s experiences with the early data on COVID-19 deaths in the Filipino community, I realized we had yet to see the full effects of this pandemic.

Affectionate and tender, nurse Lovella "Love" Eugenio rests on the shoulders of her husband, Ronald, with her dog, Mei mei, in her arms. She was among the great number of Filipino nurses who tested positive for COVID-19 in 2020, and one of the few lucky ones who recovered. It took her three weeks before she could return to work. Where before work meant juggling three nursing job, Love is now working two full-time nursing jobs.

Two months later, the first of my co-workers tested positive for COVID-19. One of them was Lovella “Love” Eugenio, a Filipina who at the time was working three nursing jobs for her intergenerational family.

Love, like her namesake, is full of tenderness and warmth. She told me as she was getting ready for work after recovering for three weeks, “I am not a 100% yet. I still have to catch my breath sometimes.” This encounter really moved me. I wondered, how many Filipinos are yet to be 100%, but are going back to the COVID-19 frontlines to provide for their families? What are the stories behind these sacrifices? This became the groundwork for my project documenting the Filipino nursing diaspora.

By June 2020, the Los Angeles Times reported that Filipino Americans were dying at an alarming rate in California. Three months later, the National Nurses United Union reported that nearly 32 percent of the registered nurses who have died of COVID-19 and related complications are of Filipino descent. I was saddened, alarmed and enraged.

At the operating room of a Maryland hospital, nurses need to balance patient care, supply shortages, and the constantly evolving policies and procedures.

I started reading about the history of Filipino nurses, which shamefully I did not know. I was stunned to learn that Americans established the nursing profession as it currently exists in the Philippines during its 48-year occupation from 1898 to 1946.

In the book A History of Nursing (1912), Mary Adelaide Nutting describes how Filipino nurses were asked to speak in English, to move away from their traditional clothing, and ultimately to favor American bodies, standards, language, and culture. In the book Empire of Care (2003), Catherine Ceniza Choy explores how these Americanized ideals were further enforced with the rise of study-abroad and socioeconomic opportunities when nursing careers were further pursued in the United States.

I learned that the first large wave of Filipino immigrants began after World War II when the U.S. created the Exchange Visitor Program (EVP), which facilitated the entry of foreign nationals to help ease labor shortages. In 1948, the Philippines and the U.S. entered into an agreement for the financing of bi-national centers to coordinate educational exchange programs in various fields, including healthcare. By the 1960s, the demand for nurses increased dramatically following the passage of Medicare and Medicaid and the 1980s AIDS epidemic.

Mark Bontogon making sure his PPE is secured, before attending to patients at the Doctors Community Hospital in Maryland.

Mark enjoying the massage chair he gave himself as a means to relax after a long strenuous duty as a night shift telemetry nurse.

Ella Bontogon, a new nursing graduate, has taken up painting to rest, relax, and cope.

Looking at this history, I am learning that Filipino nurses have been on the frontlines of many health crises over the years, and it is not by accident.

I met Marc Bontogon, Ella Bontogon, Ernest Capadngan and Elizabeth Grace Capadngan in college. We were all first-generation immigrants who moved right before college and were encouraged to become nurses.

Marc told me that becoming a nurse felt natural. “I knew that nursing would be a stepping stone to fulfilling the American dream.” Marc often volunteers to care for COVID-19 patients during his 60 hour weeks as a night shift telemetry nurse.

After his shift, I watched him drift off to sleep in a massage chair he gifted himself as a means to relax. His sister, Ella, sat quietly painting in their living room. Ella is a new graduate nurse trying to find her footing in the middle of the pandemic. Painting has provided her a means to relax and cope.

In a home a few streets over, I met with Ernest and Elizabeth Grace. Ernest has been working as an intensive care nurse in the biocontainment unit since the start of the pandemic. He has seen COVID-19 patients die daily. He shares with me humorous memes which have helped him cope with the constant grief at work.

His wife, Elizabeth Grace, works opposite shifts as a night telemetry nurse. Despite the hardships, nursing has provided a sturdy lifeline for the couple as they settle in their new home with their newborn, Eliana Grace.

Elizabeth Grace Capadngan works as a night telemetry nurse at Doctors Community Hospital in Maryland.

Elizabeth Grace after a night shift, with her husband Ernest, who is an intensive care nurse stationed in the biocontainment unit.

Elizabeth and Ernest, who work opposite shifts, share a meal before Ernest goes to work.

In my research, I learned that more than 150,000 Filipino nurses have migrated to the United States since the 1960s, making us the largest group of immigrant nurses in the country. We are part of the estimated 10 million Filipinos working overseas that send back more than $30 billion per year in remittances, about 10 percent of the Philippines’ gross domestic product.

Mark Abordo, a trauma orthopedic nurse, has been sending money to the Philippines every month for the past 11 years. He shares with me that before the pandemic, he worked an additional 12-hour shift every week to send extra money home. He helped a cousin get through school and pays for his mother’s expenses, such as food and utilities.

Mark shares a home with Brian Chavez and their two dogs. Brian is balancing life as an emergency room nurse and a doctorate student.

Brian Chaves and Mark Abordo after their nursing shift. Brian is an emergency room nurse and a doctorate student, while Mark is a trauma orthopaedic nurse, who works an additional 12-hour shifts every week to send extra money home.

I realized that many of the nurses I spent time with have already lived through much of the growing pains of migration.

I was able to connect with Jennifer Bulaong, a nurse who is completing her three-year commitment with a recruiting agency. Similar to my mother’s immigration story, I knew that there would be heavy trade-offs. For Jennifer, a large part her salary is taken by the agency until she completes her work commitment.

Still, Jennifer carries on. “It has been difficult to be away from my family,” she told me.

Jennifer’s mom Leane is also a nurse. She left the Philippines 12 years ago. When Leane eventually settled in the U.S., she was able to bring her mother, husband, and a younger daughter, leaving Jennifer behind. They all realized that the only way they could all be reunited is for Jennifer to become a nurse in America.

The Bulaong family in the US after Leane (Center), a nurse, left the Philippines 12 years ago and eventually settled in the US. She was able to bring her husband, mother, a younger daughter but not Jennifer, who was left behind because of visa restrictions.

Leane Bulaong hugging both her daughters before Jennifer (L) leaves to complete a three-year commitment with a recruiting agency.

Throughout this experience, I have been able to more deeply connect with the Filipino nursing community. Despite our backgrounds, we are united through a shared history that shaped us to be here, and a shared present as we fight the pandemic.

Although COVID-19 is far from over, I take comfort and pride in being part of this diaspora on the frontlines, contributing to the overall wellness of the world.

This work was supported by the National Geographic Society's COVID-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists.