We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

Names have been changed to protect the identities of the survivors. Details in this story may trigger survivors of domestic abuse.

There was a riddle attached to loving a man like him.

Like a little girl plucking petals off a dead flower, she would murmur: He loves me. He loves me not. He loves me. He loves me not.

Some nights were filled with contagious laughter and others with horrified screams. Georgina always had to guess.

There was not quite as much guessing, of course, at the very beginning. When Georgina met Lucas, she knew he was The One. “He was the most romantic, loving, and caring man I’ve ever seen,” Georgina said.

Their relationship started out rocky — Lucas was still finalizing his divorce with his second wife. But Georgina fell head over heels in love. How could she not? He told her that he loved her, that he was choosing her, that he’d do everything to win her trust and love. She loved how he pursued her.

Lucas, who Georgina met while she was working abroad, even converted to her religion just to prove how devoted he was to her.

“I thought he was the one for me. I really thought he was a gift from God because he did everything just to make me happy during the relationship,” the Filipina said. “He loved flaunting me to his friends, he’d tell me that I am perfect, that I have the characteristics that he was looking for in a woman.”

She added, “He’d tell me he wasn’t even in love. Love is a simple word. He said that he was besotted, like it’s more than love, like he would think that I am his woman. There’s this feeling in his heart that hurt and yet felt good, the feeling that he loved me so much. Those were the words he’d tell me during the relationship and I believed him.”

They were together for three years before Lucas and Georgina decided to get married. But the beginning of their happily-ever-after gave a glimpse of an incoming hell that would last for seven years.

On the eve of their wedding, Lucas and Georgina got into a big fight. There was a photo shoot and a church rehearsal waiting for them but Lucas did not want to be a part of any of it. He wanted to spend time with his friends and drink the night away, Georgina said.

“I noticed that his attitude suddenly changed. He wanted to enjoy the night with his friends, he was banging stuff. He was so grumpy,” Georgina said.

In the middle of the fight, Lucas opened his mouth to say words that will forever be etched in her memories.

“He told me I am a fuck Filipino shit from the third world country. Who was I to control him? He won the war. That’s what he would tell me,” Georgina said.

After tasting verbal abuse for the first time, Georgina couldn’t bear to marry Lucas anymore. But a friend convinced her to push through, anyway. After all, fights before tying the knot were just “wedding glitches,” the friend said. It happened to everyone. Georgina and Lucas exchanged their “I do’s.”

But things just got worse after their promises of forever.

He was drunk when he drove her to the hospital as she was about to give birth to their only child. He left her alone with her newborn son after a 16-hour labor, as Lucas went out drinking again with his friends. When his drinking ended up affecting his career, he found himself in and out of jobs.

Whenever he’d get drunk and they’d fight, Lucas would tell Georgina the different ways he’d kill her.

“He’d tell me that he would do 15 years in jail just so he could cut my throat. He’d tell me that I’m a disgrace to society, that I am the worst fuck and he fucked better. He’d tell me that all I did was open my legs and I had a happy life,” she said, tearfully.

“He’d say his verbal threats again and again. How he’d burn my car, how he’d burn our house. He’d be the last to hammer a nail in my coffin, he’d cut my throat one day, he can see it coming.”

But Lucas would strike a different tone when he sobered up. “When he’s OK, I ask him, ‘Why’d you call me these things?’ And he wouldn’t remember, or he would deny saying those things.”

As if the verbal abuse weren’t enough, Georgina also lost so much of her life: her freedom, her security, and her own peace.

“There were so many cases when I’d leave, even if it’s work-related, and he’d accuse me of having another man. He even tried to put a GPS on my car. He even told our common friends that I had another guy, even if I just went out for only two hours. It was not acceptable to him,” Georgina said.

Worse, Lucas even approached Georgina’s boss and her company’s HR department to ask why she had to work on her days off.

During company events where Georgina would bring her husband, Lucas would get furious if he ever saw her talking to somebody else. She remembers a company party where Lucas got angry at her while they were just still at the parking lot. “He kept telling me that he’d sue me for adultery, that I’d go to jail and he would take my son. If it wasn’t for him, my job wouldn’t be as great, but he had no contribution there,” she said.

And the act of simply spending time with friends became a problem. Once, Georgina was invited by her colleagues to a house party, and Lucas “allowed” her only to take it out on her at the end of the night.

“I asked his permission if I could go,” Georgina said. “He said OK but he walked me to the taxi, he took the taxi driver’s name, contact number, he took a picture of the taxi. He told me that he would know where I would be going.

“I haven’t been at the house [party] for longer than 30 minutes when he already left 18 missed calls. He told me that when I got home, my car would be burning because I was having an affair. In one of his messages he told me to go outside the house because he was outside. I did go out but he wasn’t there. I just went home after that.”

Despite Lucas’ paranoia about Georgina having an affair, he was the one who was caught cheating, multiple times, through seven years of living together.

Georgina would find photos and conversations with other women in Lucas’ phone. She would even learn of one particular woman that her husband would bring to the same salons she went to, have the woman’s nails painted the same way Georgina did. He would even gift her the same shoes Georgina owned.

Her son became a witness to all this abuse, and would even receive some of it.

“Sometimes he’d say, ‘Mommy, Daddy is sleeping in the bathroom naked. Mommy, Daddy is sleeping in the corridor,’” Georgina said. “He’s been calling him ‘little cunt,’ ‘fuck off,’ ‘fuck you,’ ‘little dickhead.’”

Her son would be so scared of his own father that whenever he’d find out that Lucas wasn’t home, he would visibly show excitement.

One scary moment happened when she was trying to convince her son to take a bath.

“My husband got mad and dragged my son. He grabbed him by the shirt going up the second floor. I was trying to stop him because he was drunk and he was pushing my son to the corner of the bathroom to shower. I saw my son was so scared,” she said.

Georgina didn’t have many friends in the country where they lived, and she didn’t have much of a life outside of Lucas, her son and her work.

“There was a pattern to his behavior,” Georgina said. “And when we made up, he’ll go back to the romantic guy but it wouldn’t last. His good side wouldn’t last. His bad side would always come back.”

Abuse, according to the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), happens in an identifiable cycle. First comes the abuse: the anger, the threats, the intimidation.

After the incident comes the “reconciliation” stage, when the abuser apologizes, gives excuses, denies the abuse occurred, blames the victim, or even says the incident wasn’t as bad as the victim claims.

Then comes the “calm” when the incident is forgotten, no abuse takes place and it’s the “honeymoon phase” once again. But then the tension would build and the abuse takes place once more, and so it goes.

Even women who come from well-off backgrounds, are smart, or have a good career, can still go back to abusive relationships. “As long as the victims feel like there’s a little bit of remorse, they go back to the relationship,” said EnGendeRights Executive Director Clara Padilla, a women’s rights lawyer.

Through her hell, Georgina found a reason to endure. “The abuse that I had, the threats he’d tell me, I had to deal with them, not for me but for my son.”

On several occasions, Georgina asked for a separation because she just couldn’t take it anymore.

“What he’d do when we’d reach that point is he’d empty our joint bank account. He was threatening to cancel my son’s visa. He even cancelled my mom’s visa one time... I didn’t have any choice but to stay and he’d always remind me that in that country, the law is always favorable to the men, to those who have the money to sustain the children. He’ll get our son.”

Although Georgina’s story feels like hell come to life, it’s a story experienced by many women behind closed doors in the Philippines.

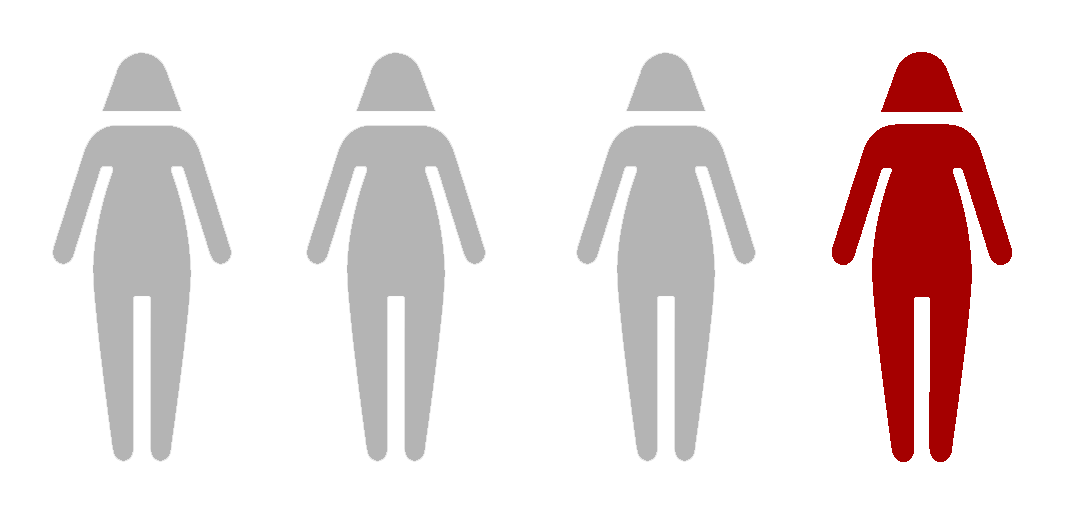

According to the 2017 National Demographic Health Survey, one in four Filipino women between ages 15 to 49 years old have experienced physical, emotional or sexual violence by their husband or partner.

A United Nations Population Fund and University of the Philippines Population Institute study, meanwhile, reports that 12,100 women have experienced intimate partner violence every month from March to December 2020.

Violence against women appears in many forms: psychological, verbal, emotional, physical, sexual and even financial abuse.

“Power relations is the root of everything,” University of the Philippines sociologist Athena Presto said. “We socialize men and women differently. We socialize to defer the decision of the man. We socialize boys to be assertive, take everything you can take, and all of these things are carried into adulthood and being carried into more serious and more alarming offenses like rape and different kinds of gender-based abuse.”

“Why does a man think that he has a right over a woman's body? Because that was how he was socialized. That is what different powerful institutions are instilling in him. The audacity to take something that is not yours and the audacity to think that you can get away with it is something that we are socializing men into thinking,” she added.

This isn’t surprising, according to Presto, since many institutions support and say that men own their children and their wives. Domestic abuse then becomes a man’s way of expressing control over women to retain power, especially since societal norms tell men to take on “dominant roles in society” while women are dictated to merely be “men’s companions and supporters,” and take on subordinate roles.

With the never-ending numbers, the Philippine Commission on Women considers violence against women one of the country’s pervasive social problems.

Just before the lockdown, Georgina, Lucas, and their son came back to the Philippines after Lucas got a job in the country. Leaving a good career abroad behind, Georgina agreed to settle back here after Lucas promised her that they can work on their family together.

“Our relationship was OK. Then, when we came here, just a few weeks before we got our own house, COVID-19 came,” Georgina said.

They were still planning to try for a second baby when Lucas turned distant and abusive once again. She soon found out that he’d been visiting motels with another woman.

“He admitted that he made a mistake again, but this is not his mistake alone. I have a big contribution to it, he said, because I made him unhappy. He comes home and I’m not well-dressed,” Georgina said.

When a big storm hit the country, Georgina had to leave home with her son temporarily. When she returned, Lucas had changed the locks.

“I just found out he bought another house because he paid for it through our bank,” Georgina said. “He took everything. He closed our joint bank account, he took all the things inside our home, he changed the keys to our house. He took our furniture that came from other countries.”

She added, “He took everything and moved it to his house with his mistress.”

One in four Filipino women between ages 15 to 49 years old have experienced physical, emotional, or sexual violence by their husband or partner, according to the 2017 National Demographic Health Survey. The Philippine Commission on Women considers domestic abuse one of the most prevalent social problems in the country.

“I thought he would change,” Mae said.

Through 28 years of marriage with Rodrigo, she always held out hope that one day, he would stop.

Mae met him when she was just 20. He was a part-time student who worked as a security guard near her home. Mae thought that the man she met was kind and flawless. He even made an effort to be close to her family. It took a year in the relationship for him to show his true colors.

“He was very jealous and very controlling,” Mae said.

Mae couldn’t get a haircut without Rodrigo getting mad because she “didn’t ask for his permission.” She couldn’t wear mini skirts and she couldn’t go out alone. She always had to ask for his permission for even the smallest things. There even came a point when he would get jealous of his own uncle and brothers.

“I was young, and I was glad because, ‘Ay, he really loves me’ because he’s getting jealous. But that was wrong. He was getting possessive. It wasn’t just jealousy anymore.”

Then she got pregnant. She had to get married because Mae’s job at a big company didn’t allow unwed mothers on its staff. Rodrigo only got worse.

“In the beginning, when he’d get jealous, he’d slap me. At first, I’d fight back, but if you fight back, he’s really going to kill you. That’s why I decided to keep quiet most of the time,” Mae said, adding she couldn’t remember all the incidents; there were just too many.

“At first, it was just slaps, until he began to punch me in different parts of my body. Since I had work, he’d punch me in places where bruises were hidden, like my arms and legs.”

He even beat her when she was four months pregnant. Out of fear for her life, Mae jumped into a river just to escape, never mind if she did not know how to properly swim. Even then, he ran after her.

Life at home was hell. When he came home and there was no dinner, Rodrigo would throw pots at Mae. If he didn’t like how she answered a question, he’d throw the glass he was drinking from at her. If she cut the bangus wrong, he would flip over the table. If she served pork and beans and he did not like it, he would push the can against her face.

If he was not laying his hand on her, she would still get verbal lashings that would make her feel like the smallest person.

“He would curse at me, in a terrible way. He would tell me I could only become a secretary and nothing more. He’d insult me by telling me I wasn’t a virgin anymore as if virginity was the only basis of my personhood. He’d accuse me of cheating and tell me I had a rotten organ because of the affairs I’ve allegedly been in. It’s all very humiliating.”

The abuse did not stay private.

“He’d humiliate me in public. For example at the cashier in the department store, he’d tell me, ‘Who told you to get that? You’re spending so much. Put that back!’ He’d turn you into a kid,” Mae said. “When we’re in the car and he’s driving, if you just glance at the window and there’s a man standing there, he’d slap me and tell me that I liked the man outside.”

The jealousy only got worse. “He’d always say that our neighbor was my boyfriend. He would accuse me of having a relationship with his brother, his friend, any man he saw,” Mae said.

It turned out that Rodrigo was guilty of the very thing he kept accusing Mae of doing.

“I had officemates that he pursued. He was a womanizer. My officemates would tell me because they were so shocked. ‘I saw your husband in the bus. He touched my leg.’ He was a pervert,” Mae said.

She worked hard but Rodrigo was in charge money. In fact, he controlled every centavo, even the amount she can spend for their household.

All five of their children bore witness to their own father’s abuse.

“I wish the kids didn’t see, but he’d show it. He’d even hurt the children,” Mae said. “He’d slap them, punch them in the stomach.”

She added, “He liked being massaged by my kids. He wanted his legs to be pressed on and if the massage wasn’t good, he’d punch them.”

Sometimes, Mae would end up wondering what she did to deserve such a cruel fate.

“Of course, I’d think to myself, ‘Why did I end up with this person? Why is he telling me these things?’ He met me when I was just a student graduating from college. I come from a good family. My family doesn’t fight, that’s why it’s shocking I had this relationship.”

Once, she woke up at two in the morning to find Rodrigo standing over her. His feet were planted on each side of her resting body. He held a long blade to her neck.

“There it was, only two inches away from me. I was so scared. I kept crying. I couldn’t move because he might kill me. That’s what I can’t forget because I really shook in fear,” Mae said.

But every time he’d hurt her, Mae knew an apology would come soon after.

“He’d say sorry the next day. He didn’t mean it. He’d even go down on his knees. He’d hug you and kiss you and say it won’t happen again. I’d escape so many times but he’d still find me again. They call it the cycle of abuse,” Mae said.

Through all the hell he put her through, Mae recalls just loving him.

“I guess I loved him so much even when he had other women. I don’t know, I guess I was blind in love,” she added. “I just thought to myself that he’d change and this is where I already was. I thought to myself that he’d change and I’d just tolerate it until then,” Mae said. “It was like I just hoped this person, this man will change.”

“I bore it all because he was providing for my children’s education, their allowance, their tuition. I stayed in the relationship for my children. I stayed because I wanted a complete family. But nothing happened because that was who he was,” she added.

Studies show that some Filipino women have also been able to justify the abuse they take to themselves, an effect of the cycle of violence they’ve experienced.

“Some will say that it’s OK to get beaten up if they accidentally burn what they’re cooking, if they accidentally fail to look out for their children for a bit, if they went out without telling their husband,” said Clara Padilla, the women’s rights lawyer.. “They think that what men say is always right. That’s patriarchy and sexism at work. At the same time, the cycle of violence is there.”

Others, meanwhile, would find excuses for their husbands and partners.

“Alcohol and drug use are also blamed. Before, the patriarchal power over women would just say, ‘Ay, he was drunk,’ as if he wouldn’t be beating his partner if he wasn’t drunk or on drugs,” said Nathalie Africa-Verceles, the director of the University of the Philippines Center for Women’s and Gender Studies.

In fact, the blame ought to lay solely on the abusers, who are likely to have undiagnosed psychiatric disorders and narcissistic personalities.

“Whenever they commit crimes, batter, rape people, these types, it’s already a disorder and apart from the fact that they’re sexist, patriarchal, if they were abused in the past, it becomes a learned behavior,” Padilla said. “They never get counseling because more often than not, because they are narcissistic, they do not admit that they are at fault.”

In any case, the blame should never be on the women.

“Nobody deserves violence. They never wanted that,” said Mae Jardiniano of Women’s Care Center, Inc., an organization that provides assistance to survivors of gender-based violence. “They’ll say they love the man but if they go through counselling, they’ll realize that what they’re saying is wrong.”

Abuse affects not just women’s physical health, it also affects them emotionally and mentally. They cause women to feel ashamed and lose their self-esteem, and threatens survivors’ own personal security.

“The cycle of abuse can be so intense, it can be so prolonged that even with marital rape happening, women still bear it. Some bear it for their children. Some, I’ve noticed, last up to 20 years, 15 years. They’re just waiting for their children to grow up. Once their children are adults, that’s the only time they leave,” Padilla said.

Another common reason women leave is when they discover an extramarital affair, when they’re sure that they’ve been replaced, Padilla added.

“The third reason,” she said, “is if it already becomes really extreme.”

For almost a decade, Mae didn’t tell anyone about the abuse she’s suffered at the hands of Rodrigo.

“I didn’t have anyone to go to,” she began. Mae hid it from her parents for a very long time. When they would visit and saw she had a black eye, they turned suspicious. “I told them that I accidentally hit myself but they didn’t believe me.”

Her whole family, even her children, pushed her to leave. “My children, my eldest and my daughter would tell me to get away from him because he ‘might kill you.’”

It did not help that when she went to the police, the whole thing just backfired on her.

“They just told me it was ‘away-pamilya,’ a family quarrel,” Mae said.

This is a common refrain, according to Athena Presto, the University of the Philippines sociologist. “If you look at the data, it’s the norm here in the Philippines to abuse your wife and abuse your girlfriend or to abuse even your children. It’s normal for us that your partner pushes you to have sex at night and it’s normal to hear people say that you should just give in, ‘he’s your partner anyway,’” she said.

Mae finally found the courage in 2004, when Republic Act 9262, also known as the Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Law, was enacted. By then, Mae had been suffering for 28 long years.

R.A. 9262 seeks to address the prevalence of violence against women and their children by their intimate partners no matter the gender, be it their former husbands, live-in partners, boyfriend or girlfriends. The law doesn’t just protect married women, but any woman with whom the offender had a sexual, dating, or intimate relationship with. Children, legitimate and illegitimate, of the woman arealso protected by the law.

Under R.A. 9262, the survivor may file a criminal action against the abuser or apply for a protection order that safeguards the survivor from further harm. It’s not just the survivor who can file a complaint, but any citizen having personal knowledge of the circumstances involving the crime may file a complaint since “violence against women and their children is considered a public crime.”

The criminal complaint can be filed within 20 years from the occurrence of the crime that resulted in either physical, sexual, psychological, or economic abuse including acts of cheating, violent threats, financial support withdrawal, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty.

“These ‘just give in, it’s your partner anyway,’ these seemingly normal things are what the law corrects,” Presto said.

The law carries a penalty of imprisonment ranging from one month and a day to 20 years. They will also be penalized with payment of P100,000 to P300,000 in damages.

Under the law, barangay officials, police or social workers are not allowed to mediate or influence the women to give up her legal action. But this isn’t always followed, said Presto. Women from impoverished municipalities have told her that, in fact, the law complicates matters for them.

“The law says that they should have all these seminars and these seminars will make them aware of the different kinds of abuse that are being done to them,” Presto said. “But when they actually tried to get in touch with municipal social workers or development officers, family members of both the wife and the husband would come together and tell the woman to stand down. They’d tell her, ‘Aren’t you ashamed? Everyone will know that this is what’s happening in your family. Don’t you take pity on your children? They won’t be able to live because your partner is the only one working.’”

She added, “So it’s like it’s their fault. They think it’s a double burden because it’s such a torture to be able to know all of these things but also to feel helpless amid all these knowledge that you are beign abused.”

Some are even told, like Mae, that their reports are mere family quarrels. But with the large number of violence being committed against women, Presto said things should no longer be treated as a private matter.

“It is something that is being experienced by a lot of people, something that endangers a lot of women, if not all women, so it shouldn’t be seen as simply a fight between couples,” she said.

Out of 42,045 barangays in the country, 38,824 or 92.34% barangays have Violence Against Women desks.

Out of the 38,824 barangays with VAW desks, only 7,553 or 19.34% have reached the highest level of functionality.

Barangay Violence Against Women (VAW) desks are the first responders in protecting survivors since they are the closest when there is danger.

Republic Act No. 9710 or the Magna Carta of Women mandates that every barangay must establish a VAW desk. But while almost all barangays have established VAW desks, they are still yet to be fully functional and gender-sensitive.

“The data from the Department of Interior Local Government shows that 92% of barangays nationwide all have existing VAW desks but the assessment reveals that only 19% of the 38,924 barangays have reached the highest level of a functionality,” said PCW Information Officer Nevi Calma.

“We are trying to coordinate with all the agency involved and DILG has been continuously guiding our barangay VAW desks and capacitating them so they may be able to respond correctly, and with the gender lens they will be able to respond correctly to the different VAW cases.”

Although there has been “efforts” to establish VAW desks correctly, Africa-Verceles continues to hear of cases wherein barangay captains have attempted to mediate between the partners and reconcile the pair instead of issuing a barangay protection order.

Padilla added that there is already a circular from the PCW, DILG, and Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) recommending barangay officials be trained, but this is far from reality on the ground. “If you don’t have a good sexuality education, you don’t teach gender, gender violence against women, even the legal remedies, if these aren’t talked about, there will still be problems at the barangay level,” Padilla said.

Mae’s children were already grown up by the time she mustered enough courage to leave Rodrigo.

She was reading the newspaper when she saw an ad about an organization that helps survivors of violence. Mae dialed the contact number.

“There was no R.A. 9262 back then,” Mae said. But “they told me if I wanted to leave, I should fix my things because the abuse will just repeat especially if they have other women.”

Mae took a chance when Rodrigo wasn’t at home and paid the center a visit. When she came back, Rodrigo was waiting for her.

“When I entered through the door, he grabbed my hair. He was a big man. He pulled my hair and threw me on the sofa. I rolled over and he grabbed my hair again and pulled me up to the second floor. There he made me remove my clothes,” Mae said.

After R.A. 9262 was implemented, Mae decided to get a barangay protection order against him. With the order, Rodrigo was forbidden by law to lay a finger on Mae. But Rodrigo beat Mae again with a telephone when he found her talking to his aunt.

Her daughter called the cops after that incident.

“The police came and he started crying. He was throwing a fit on the street in front of our house. It was drizzling then. He said, ‘Go, arrest me! Just kill me!’ He was like a child lying down on the street in the rain. Is that something a sane person would do?” Mae said.

They went to the municipal hall, where he continued to beg their children to drop the charges.

But Mae was initially adamant to send him to jail. “What a waste it didn’t push through.”

But when they reached the women’s desk, she simply told him, “Get out of the house. Send us money, but don’t ever come back again.”

He walked away free, but despite their agreement, he rarely sent money. Mae had to work hard to make ends meet, but after 28 years of living in fear, it was a worthy price to pay to finally be free.

According to data from the Department of Social Welfare and Development said 7,833 cases of violence against women were reported from March 15 to October 31, 2019. In the same period in 2020, during the lockdown amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of reports dropped all the way down to 3,593.

The Public Attorney’s Office handled 7,353 cases of violence against women and children in 2019, but only 5,175 in 2020. In Metro Manila, PAO handled 1,811 in 2019 but only 983 in 2020. Region III and CALABARZON had the highest number of cases in the past two years, while PAO in BARMM handled absolutely zero cases of violence against women.

According to experts, however, the drop in number is far from good news, because the pandemic may simply be preventing victims from reporting on their abusers.

“It goes down because they’re scared to report. They’re scared to report because of COVID-19,” said EnGendeRights Executive Director Clara Padilla, a women’s rights lawyer.

With restricted movement in communities and suspension of public transport, it becomes harder for survivors to leave their homes to report their abusers.

Being locked down with the perpetrators also make it harder for women to call for help, with the lack of privacy in their homes.

Aside from being isolated and being unable to escape, victims also have to worry about their own physical security and emotional distress as they continue to live with violence.

The pandemic, experts said, not only affected the chances of victims reporting the abuses they endure, but also their vulnerability to abuse.

“Incidents of domestic violence increase especially when there’s a humanitarian crisis like COVID-19,” Padilla said.

Nevi Calma, an information officer for the Philippine Commission on Women, calls it “a perfect storm for violence against women in their homes.”

“Because there is a lot of pressure, a lot of tension inside the house, because some family members may have lost their jobs, some family members may have been put into health risks,” Calma said.

Women’s Care Center, Inc., an organization that helps women who have been victims of abuse, had a hard time referring survivors and their children to shelters since they still needed to test negative for COVID-19.

“They don’t have money. I try to talk to the shelters but they are also scared,” said Mae Jardiniano, the officer-in-charge for the organization.

Meanwhile, government resources meant to protect women were instead directed to pandemic-related concerns.

“Some of the [Violence Against Women] desks were deployed as barangay health emergency response team,” said Helen Peclarin of the Women’s Legal and Human Rights Bureau.

Groups like those of Jardiniano have begun to adapt, shifting their counselling sessions online to safely help the survivors.

According to Calma, government agencies have also tried to adapt to the new challenges amid the pandemic. “We started adjusting to the new normal so we strengthened our referral services, we opened our lines, mobile, email and even Facebook account for VAW reports,” Calma said. “This is how we adjusted so that we can receive more increase and refer more VAW cases to specific service providers.”

Calma said they’ve been receiving more reports through their Facebook page and hotline compared to the past year.

Miramel Laxa of the Department of Social Welfare and Development’s Program Management Bureau said they’ve assigned a hotline specifically for online psychosocial services and counselling.

“Our partners like the United Registered Social Workers, we were really able to partner with them during the lockdown. So what happens is whaever calls or reports they receive they course through the DSWD Central Office hotline on psychosocial services and counselling. So throught that, if the person gave their contact number, we’ll really call them,” Laxa said.

The Department of Justice has also launched e-inquest proceedings to continue hearings regarding cases of abuse amid the pandemic. The Supreme Court has also launched an e-filling system for criminal complaints.

Having come from a broken home, Cecille always wanted to have a complete family. She wanted to give her children a roof over their heads, a comfortable life, and a place to call home.

Her father was out of the picture from an early age, so it was only her mother who raised her and her sister. At 17, Cecille met an 18-year old boy who gave her flowers, showed affection, and a glimpse into what could be her own family.

“Our relationship was a secret because I didn’t want to marry young but then I had a problem with my sibling. I always fought with my sister,” Cecille said. “It was like an escape from my family. I thought that it would be better to get married. I didn’t know this would happen to me.”

Cecille thought Derek was a good man. When they started living together, the abuse started.

“I wanted to go with him to town because I was getting bored at home. He got mad at me and strangled me,” Cecille recalled. “We were fighting. I didn’t know that experience was already violence.”

Cecille first became pregnant at the age of 18. She gave birth once more three years later. She finally had a family of her own, but it was far from happy, as the abuse from Derek continued.

“He’d say all these things to torture me: about my family, about myself, how I only finished high school. I couldn’t recall the things he said to me without crying,” Cecille said.

“Once I had a fever fever and he came home late that night and slapped me four times. He was so angry at how I was taking care of the kids. He slapped me so hard, his hand left its print on my face.”

Despite everything she went through, Cecille always worried about her children and how she would raise them especially since Derek had control of their finances.

“We would always fight about money. Every time I’d ask for money for our household, he always had something to say, that I should be the one to work instead,” Cecille said.

“I didn’t realize how difficult it is to be a woman without a job, to be relying on your husband. He’d come home and start a fight about the food I prepared. You don’t have the freedom. You don’t have the money. You look so stupid running after him because here you have a sick child and you don’t have the money to get medicine. Your heart will just break for your children. You’ll always think of your children. You never think about yourself.”

Derek would be stingy with money, but Cecille would find out that he took out a loan for appliances he had bought for his mistress.

“I only found out when it was too late, when it was all paid for. I didn’t have the strength to fight for my rights,” Cecille said. “I didn’t know how to fight for my rights as a woman.”

After a huge fight, Cecille found a morsel of strength and left Derek with her kids. But tragedy struck when the home they were living was demolished.

“I had to call him because my children and I had no place to go,” Cecille said. “So we started renting a place with him.”

A housing project opened up in their area for those whose homes had to be demolished. Cecille was more than eager to take part, but the project was only open to married couples.

“I didn’t want to get married to him, but then I didn’t want to lose the housing. We got married for the housing project,” Cecille said.

After they married, Cecille gave birth to their third child. Things hardly changed with Derek, who often came home drunk and abusive.

Cecille remembers vividly when he started hitting the light bulbs with a machete. She and her children could only scream and run away.

“My child also experienced his father dousing his school items with water,” Cecille added. “There were times he’d slap me. He would beat me in places the bruises won’t be seen on my body.”

She began to work to make extra money for her youngest child, who had kidney stones and asthma. She began helping out her mother, before starting out as a masseuse.

In response, Derek would belittle Cecille’s new job.

“It’s so hard to wait for him to take pity and hand us some money. It’s hard not having money... it’s like you need to follow him around because he’s the breadwinner. If you have a job, you won’t have to rely on him. You won’t have to chase him for anything,” Cecille said.

Many women in abusive relationships hesitate to leave their partners when they don’t have income of their own.

It’s only through a strong support system that includes family, financial aid, legal assistance, barangay social workers, among others, that victims gain the courage to leave.

“When they’ve talked to the barangay several times, the police, social worker, lawyers, that’s when they get the courage,” said said EnGendeRights Executive Director Clara Padilla, a women’s rights lawyer.

When Cecille went to the city hall to get a copy of her marriage certificate, she found out that Derek was married to two other women.

Adding to the torment, Derek would come home wearing clothes with another woman’s name stitched on it. Cecille admitted to removing it and changing it to hers, and it resulted in a silent war between her and the other woman.

The abuses and the insults where already adding up, but what pushed her to break free was when Derek slapped their child, leaving her mouth bleeding. Cecille filed for a protection order and sued him for bigamy.

But his family discouraged Cecille from suing because Derek was “the father of her children.” That argument resonated with her.

“They told me to have pity on the children. And I started thinking if he does go to jail, what will that prove? Can I raise my children and give them a good life?” Cecille said.

Aside from financial reasons, many women hesitate to leave abusive relationships because of pressure from people closest to them.

“People will tell her that marriage isn’t just rice that you can spit out. To leave an abusive relationship would mean ‘wrecking’ the family — and that’s our problem,” UP Center for Women’s and Gender Studies Director Africa-Verceles said. “We’re not very open to women leaving their partners.”

Experts note how Philippine society continues to put the blame on women for failures of their relationships.

“When you become a mother, you are expected to take in all sacrifices,” sociologist Athena Presto said. “Even if a woman is too tired from work — her partner is tired from work as well — but she’s expected to cook the rice, do the laundry, teach the kids math... This is how powerful the socialization process can be.”

From a young age, Filipino women are socialized to shrink themselves so others can take space.

“We expect her to be the one to adjust. ‘You already knew he was a womanizer, why did you marry him still? You knew he beat you up before, you still married him and you still haven’t left him,’” Presto said. “So it appears that women have to adjust because boys will be boys. So because that’s just how they are, there’s nothing we can do about it, it should be up to us, so if you can’t escape the relationship it’s your fault.”

These societal norms, said Africa-Verceles, discourage women from reporting abuse.

In the end, Cecille decided to withdraw her case against Derek. “I just want a peaceful life. I thought to myself that he’s still the father of my children. The case progressed and I got scared.”

But at least, she was finally free of him. “He was also afraid. He couldn’t harass me, he couldn’t hurt me, he couldn’t abuse me, and say abusive words, curse me and insult me anymore.”

Gender equality is one of the Social Development Goals of the United Nations. But while the Philippines has made headway in terms of equality, violence against women remains a big challenge.

Cecille continues to work day in and day out to sustain her family. She’s now into papercraft not only as a hobby but as a source of income.

“I’m finding ways because he’s not giving the proper support. In terms of financial, I really had a hard time because I have a lot of kids,” Cecille said.

After leaving her husband of 28 years, Mae is now living life to the fullest. She has attended numerous livelihood trainings and has even gone abroad for a year to take on a new job. She’s also learned self-defense and is giving lessons to other survivors.

“When I was able to be free of him, I went back to my hobby... of mountaineering. I’d climb mountains, I’d go mountaineering, a certified mountaineer. I told myself I wanted to experience all the things I wasn’t able to when I married him,” Mae said.

Things aren’t quite settled for Georgina. After her separation from her husband, she reached out to Women’s Care Center, Inc., which assists survivors of gender-based violence. The organization advised her to report to the police, get a lawyer, and undergo psychological evaluation.

She was able to get a temporary protection order and file a criminal complaint against Lucas. she is yet to be granted a permanent protection order. Since they were married in the Philippines, the abuses she experienced even if they happened abroad remained grounds for her case.

“I will live with financial debt because we still have to pay for something as husband and wife. We have loans right now, and I am financially struggling and it is also considered economic abuse so hopefully the court will order this permanent protection order,” Georgina said. “I was not familiar that VAWC [R.A. 9262] is existing to be honest because I was living in another country for years.”

But although Georgina’s case remains unresolved, she is now finding ways to explore her life like she hasn’t before. “I’ve come to the point where I have my acceptance already,” she said. “It’s time for me to love myself, to focus on my child.”

She continues to worry about her son’s mental health and the effect of her husband’s abuse on him, so she’s been trying to find ways to guide him so he won’t turn up to be like his father.

“I am thinking to be honest that this is happening to me because God has a better plan, that I think I would be better without him, that my life, my sanity, my career, my freedom, all of these I can achieve now that he’s not around,” Georgina said.

Georgina sees hope in the law. “The VAWC [R.A. 9262] covers your psychological, covers the verbal abuse you’ve been through, covers his threats of not giving support, those things that we thought we didn’t have a chance with, that we’d have a hard time with.”

But while the law is helpful, there are a lot of challenges when it comes to implementation. Filing for permanent protection orders and criminal complaints can be a lengthy and expensive process.

“If it’s a criminal case it can last a minimum of three years,” said Clara Padilla, the womens right’s lawyer. A protection order may come faster, with permanent protection usually taking longer than a temporary one. “You’re lucky if you can get the permanent order in eight months,” Padilla added.

Delays happen when respondents won’t appear in court, or when issues of custody, support, and control over property come into the discussion.

“Our problem is when there’s a delay in justice. If the marriage isn’t nullified immediately, the survivor and the kids will be at risk,” Padilla said. “While the case is still hanging, the perpetrator can abuse other women because abusers are usually the ones who get into relationships. I have a lot cases like that.”

For this reason, Padilla says, there needs to be a serious discussion of divorce in the country. The process of divorce is much shorter and much cheaper, compared to getting a marriage annulled, which requires evidence-gathering and other expenses.

There is also the question of support. “It’s not only child support, it’s alimony. In ours, when you get [your marriage] nullified, the wife doesn’t get support but in divorce, you can get alimony even if it’s limited.”

She shuts down the arguments that allowing divorce would lead to broken homes.

“For those with happy relationships, we don’t have a problem, they don’t need to file for divorce but for those in abusive relationships, divorce is very important... the custody, visitation, alimony, support will be in order,” Padilla said.

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority, only one out of three Filipino women who experienced abuse have sought help.

Experts say that all elements of the system need to step up, from social workers, prosecutors, police, barangay officials, lawyers and judges.

“There has to be sensitivity in terms of recognizing the abuse. Sometimes, it’s not apparent to the social worker because they think, oh, the child bathes, we can talk to the child properly, the child speaks in English, but if they dig deeper, if they interview the mother and perhaps the people around or make a surprise visit, it’s very important,” Padilla said added.

Although groups encourage victims to seek help, it’s something that cannot be forced because there are multiple factors at work.

“There are women who are not ready to report, there are women who are fearful to report and they are taking the time,” UP Center for Women’s and Gender Studies Director Africa-Verceles said.

This is why mainstreaming gender equality and sensitivity is important.

“Different women have different forms of coping and it is not up to them define and change the way they cope but up to us to understand and to pick up certain signs of them telling us, that ‘Hey, I’m being oppressed, would you like to help me?’” sociologist Athena Presto said.

Cecille, Mae, and Georgina may now be free of abuse, but many other women continue to experience domestic violence behind closed doors.

Having gone through hell in her marriage, Mae encourages women to leave their partners at the first sign of controlling behavior — be it turning angry for something as innocent as being late, becoming so jealous of your friends, or simply deciding what you should wear.

“Don’t continue it because he’s going to be like that. He won’t change,” Mae said. “Think about yourself because you still have hope. Don’t lose hope in life.”

Georgina, meanwhile, urges other women to find their courage.

“I’m not the only one who experienced this situation and the good thing, we women have a way to fight it,” Georgina said. “Don’t be afraid to leave abusive relationships just because we think we don’t stand a chance.”

If you or someone you know is a victim of domestic violence, please do not hesitate to contact the following for assistance:

Inter-Agency Council on Violence Against Women and their Children

Mobile numbers: 09178671907 | 09178748961

Email address: iacvawc@pcw.gov.ph

Public Attorney’s Office

(02) 8929-9436 local 106, 107 or 159 (Local “0” for operator)

Mobile: 0939-3233665

DOJ Action Center: (02) 8521-2930 / 8523-8481 loc. 403

Email address: pao_executive@yahoo.com

Philippine National Police

Hotline: 177

Aleng Pulis Hotline: 0919 777 7377

PNP Women and Children Protection Center

24/7 AVAWCD Office: (02) 8532-6690

Email address: wcpc_pnp@yahoo.com / wcpc_vawcd@yahoo.com / avawcd.wcpc@pnp.gov.ph

National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) Anti-Violence Against Women and Children Desk (VAWCD)

Taft Avenue, Manila

Hotline: 117 / 911

Women Children Protection Center

Main Office: (02) 8532-6690 / 7410-3213 / 7723-0401 local 5260, 5360, 5361

Visayas: 0917-7085157 / (032) 410-8483

Mindanao: 0917-1806037

Aleng Pulis: 0919-7777377 / 09667255961

UP-PGH Women’s Desk

Tel. nos.: (02) 8524-2990 / 8353-0667 / 8542-1512 / 8554-8400 local 2536

Women's Care Center Inc.

Vito Cruz, Manila

Mobile: 0920-9677852 / 0917-8250320

Email: wcc.inc.ph@gmail.com