We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

Written By: Kaela Malig | Social Media Producer: Julia Medina | Digital Media Producer: Shai Lagarde |

Production Assistants: Pauline Castillo, Nicole Antonio | March 11, 2021

Since they were born, they could hear the words: Women cannot do this, nor could they be that. All their lives, they have been placed in boxes nobody really saw but everyone expected.

Many Filipino women from different fields have pushed against these four walls and broken the limit as to who and what they could be. Despite facing numerous challenges, they’ve fought long and hard to get to the farthest places they could imagine and create better worlds for other women.

Challenging norms and defying expectations, these women have written: We are women. Watch us take space.

Because at the end of the day, Bakit Hindi?

Kara David wasn’t always the household name Filipinos have come to trust. Proudly starting at the bottom, her career was a string of fortunate events, held up by her own integrity and honed by the very lives she touched.

In 1995, right after college, Kara applied as a reporter for different networks and didn’t pass any.

“I applied in GMA as a reporter/writer but I wasn’t accepted. I didn’t pass the audition because back then, the English language was used in the newscast and I wasn’t very good in the English language,” the veteran journalist said.

Her parents raised her to speak in straight Filipino. Her father, Professor Randy David, had a Filipino talk show called “Truth Forum” which eventually became “Public Forum” and he needed to practice his vocabulary at home.

Laughing as she recalled, Kara knew she didn’t pass her audition at GMA the moment it ended.

“I remember seeing Ma’am Marissa Flores and Addy Pareno. They were the ones who held the audition and after the audition, I knew I didn’t pass even if they didn’t say anything. Afterwards, Ma’am Marissa talked to me and she said, ‘You want to be a PA?’" Kara said, laughing.

She was hired as a production assistant and researcher, a position she didn’t seek in the beginning, but one that in hindsight, was the right way for her to start.

“I’d like to think that I’m so blessed, I’m so grateful for that day that I was hired as a PA for GMA because I wouldn’t have it any other way. I found out I would rather start as a production assistant/researcher. I realized the reason why I write this way, why I deal this way, why I work this way is because I started to what they call at the very bottom,” Kara said.

Working as a PA, Kara learned the ropes and honed her skills in production. In a way, that’s one of the reasons she’s now considered a strict and “terror” mentor to researchers placed under her shows. She knows the ins and outs of research work.

“From there on everything was… by luck,” Kara said.

Soon, she became the PA for the 1995 election coverage and was placed under the supervision of John Manalastas.

Boss John, as she calls him, was the writer for “Brigada Siete.” He took her under his wing, when Kara told him she wanted to learn how to write.

“What he would do was, we’d write at the same time,” Kara recalls. “I’d sit at the side of his desk and he would say, ‘O, this is the topic. I’m going to write a script, and you’re going to write your own script and I’ll check.’"

Soon enough, Kara found out Boss John was already using her script in the actual show.

Kara David shares how she broke into the news industry.

Later that year, Kara would get her big break as a journalist, when Jessica Soho called the newdesk and nobody was around but her.

The ship MV Kimelody Cristy had just sunk, it was late in the evening. “Ma’am Jessica Soho called on the radio. I was transcribing an interview of another reporter because I was a PA, right?” Kara said. “And she said, ‘Desk. Desk. Lady Blue.’ We were still using the radio back then. There was no cellphone. Ma’am Jessica asked, ‘Is there anyone there?’ And I replied, ‘I’m here.’ She said, ‘And who are you?’ ‘I’m Kara.’”

Ma’am Jess she asked if there was anybody else around. “‘It’s just me, Ma’am’,” she replied.

The next thing Kara knew, she was on her way to Batangas, about to take her first plunge into unchartered territory in what will soon be her baptism by fire.

“I was really nervous that time. When I got there in the hospital, as in, the case studies I got were just like magic, were really just spectacular,” she recalled.

Kara will never forget the three people she interviewed.

There was the couple who saved their newborn baby by putting the child on a piece of Styrofoam for fruits.

There was the bride on her way home to the province for her wedding, who was crying as she held her wedding gown. To save herself, the bride used her wedding gown as her own inflatable device, hanging on to it to keep her afloat. Her wedding gown, to everyone’s surprise, was what saved her. Although it was the only thing she was able to bring home with her, she thanked the heavens that she was still alive to marry her love.

The last person she interviewed was a weeping old woman who lost her husband as the ship sank. They were holding hands but in the tragedy of it all, they were ripped apart as the woman tried to save another child from drowning.

Teary-eyed, Kara couldn’t believe the stories she had just heard. As if they weren’t heart-piercing enough, a miracle happened before her eyes.

“After like an hour, all of a sudden, here comes an old man crying coming from a different place. He was the husband, and he was looking for his wife, the old lady. And they reunited right before my eyes. It was crazy. I had goosebumps,” Kara said.

As it would turn out, Kara was the only reporter in the hospital so small and minor, it was overlooked by other reporters. “And because I’m not a main reporter, I was assigned in a lesser known hospital. ‘My God!’ I said. The story was so beautiful.”

So moved by their stories, Kara decided to write the script herself. She thought it could be something of a guide to help Ma’am Jessica understand and get to know the people behind the stories.

But when Ma’am Jessica read it, she looked up with a stoic face and told Kara, “So you can write.”

Jessica Soho proceeded to read Kara’s script on air, albeit with minor changes. Impressed by Kara’s talent, Jessica called the higher ups to give Kara a promotion.

A week later, she became a segment producer.

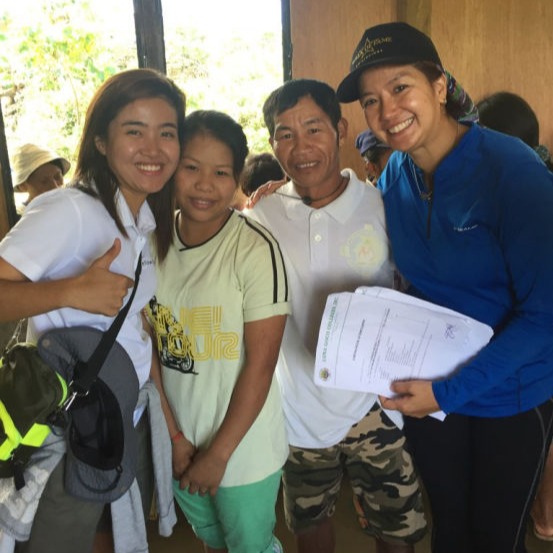

Kara David's work on I-Witness has led to all kinds of opportunities to help others.

Her first big break on television wasn’t planned either. With no reporter to interview people on the ground during the APEC Summit, Kara the writer, was sent to cover the story.

Not wanting to do a typical interview, she tried for something new.

“We went to a barangay and we looked for people playing bingo, doing their laundry. And I told the cameraman, ‘Let’s interview them while they’re doing something so it’s not the usual man on the street where they’re on the street and you just hand the camera, like you really get to feel that its natural.’”

But her cameramen Bojie Sonza and Greg Gonzales insisted she go on-camera. “They said, ‘Karing, come here. This is just for fun.’ That’s what they said,” Kara said. “‘Pretend you’re doing the report then you’ll just pass the microphone. Just for fun.’ I told them, ‘I don’t have clothes. It won’t look good.’ They answered, ‘We have clothes.’”

Soon, she was dressed in a GMA uniform and reporting right in front of the camera.

“It was just really for fun, between a cameraman and the segment producer,” Kara said. “I did a standupper then straight to the interview. Afterwards, I wrote the script.”

When veteran editor and GMA journalist Steve Serna saw her clip, they decided to use it and air it on national television.

But that’s not all her cameramen did for Kara. They went out of their way to speak to Marissa Flores, now the GMA Senior Vice President for News and Public Affairs, and lobbied for her.

“They said, “Did you see our kid? She can be our reporter, right?’” the veteran journalist said. “The cameraman said, ‘This kid has potential.’ That’s what he said. He really fought for me and Ma’am Marissa told him that she also saw my potential. So I became a reporter. I became a reporter after that incident, and everything else followed.”

She soon became a host for I-Witness after people discovered she could write documentaries and gave her a chance. When her first documentary “Gamu-gamo sa Dilim” came out, it earned high ratings and won her an award.

“It was like an accident,” Kara said. “And then I prove to them that I can do it. For a long time, I always thought that everything is just an accident and I just really, really did well,” Kara said. “But now that I think about it, there are no accidents with the Lord, right? I guess the Lord had a purpose why those accidents happened—to put me where I am right now.”

She added, “I never really aspired to become an on-cam person. I didn’t aspire to appear on camera, see myself in billboard, become a host. What I really wanted before was to write but because of the journey I had, the Lord placed me here. So there, every step is a blessing. That has been my mantra ever since.”

Although Kara David has won more awards than anyone can count — including the prestigious George Foster Peabody Award — she reveals still experiencing self-doubt “even until now.”

“I always have self-doubt. Every story that I make, I don’t make a story that’s like ‘Oh, this is so easy. We can easily do this,’” she said. “My group knows this. My team knows that after we shoot, I always ask the director, EP or cameramen or even Pauline, our PA in I-Witness, I’ll ask, ‘Do you think we have a story?’ Every time. Every episode, I always doubt if I was able to report a story.

“You can’t be too confident because as what Ma’am Marissa Flores says, ‘There is no one person that has the monopoly of all the talents and intelligence in the world. You’re only good as your last work,’” Kara said.

Even with all her accomplishments, Kara continues to be self-conscious too. “Until now I don’t watch any of my shows after 25 years. Until now. I don’t watch I-Witness. I don’t watch Pinas Sarap. I don’t watch Brigada. Anythign with my face on it, I won’t watch it because I’m afraid what I did was a failure.’”

She added, laughing, “I still have those moments so I don’t watch it on television. I only watch it if I see on Twitter and people are saying it’s good. Then I’d find it on Youtube.”

While Kara has always found inspiration in her case studies, the people behind her stories, they were also the reason she decided to resign in 2005.

She was reaping awards for the documentary “Buto’t Balat,” when Kara called it quits. “I felt unworthy because here I am, the team, the documentary that we made won an award, but I wasn’t able to help the children I interviewed,” Kara said.

The documentary entailed the journalist to interview three malnourished children, who ended up dying one after another. “Julie Ann, Angela and Jeremy, those children, they all died one after another. I tried to help. I I tried to help them but their malnutrition was so severe. And then that year we won a lot of awards.”

For Kara, it felt like she didn’t do her job as a journalist. Here she was, her team, being applauded for their documentary, when the children whose lives they featured died.

She was about to tender her resignation when her executive producer Lloyd Navera and assistant cameraman Aldrin Lacson talked to her and asked her to stay.

“They said, ‘if you stop from making documentaries, if you stop making for I-Witness, who else will tell the stories of other malnourished children?’” Kara recalled. “’And if you give up, who’s going to tell their stories?’”

“They opened my eyes when they said, ‘Get inspiration from those three children. You may not have helped them but there are still so many others who you can help’,” Kara said.

Kara withdrew her resignation, continued telling stories, and found her second wind.

On top of telling stories, she created Project Malasakit, a foundation that helps children finish their education.

Like everything else, she didn’t plan for it; rather, it was an outcome of a series of accidents.

In 2002, Kara made the documentary “Gamu-gamo sa Dilim” about an area in Mindoro Oriental with no electricity. There, she met a girl named Myra Demillo. Kara immediately fell in love with the little girl because she was full of smarts, hard work and wit.

Back in Manila, Kara received a call from Myra, who said she traveled to Manila “because I want to be just like you. I’m going to work my way in Manila.”

Afraid for Myra, Kara fetched her at the pier and told her that she needed to go home. “She said, ‘I can’t achieve any dreams if I stay in Mindoro.’ ‘That’s not true,’ I told her.”

Without knowing how she’ll do it, Kara promised to pay for Myra’s education and sent the girl back home. Without knowing how to fulfill her promise, Kara asked friends to chip in and fortunately, they were able to put Myra through college.

Soon, she took in more scholars “until our scholarship program kept on growing and growing.” To make it official, Kara soon decided to register her scholarship program, put up a website and social media accounts to spread the word. Project Malasakit, Kara’s proudest achievement, was born.

“I think the trust that was given to me in Project Malasakit comes from their trust in seeing my work in I-Witness and in other programs in GMA. And most of our scholars in Project Malasakit also come from I-Witness,” Kara said. “So if the children succeed in Project Malasakit, that’s the only time I’ll say that the documentary we did was successful.”

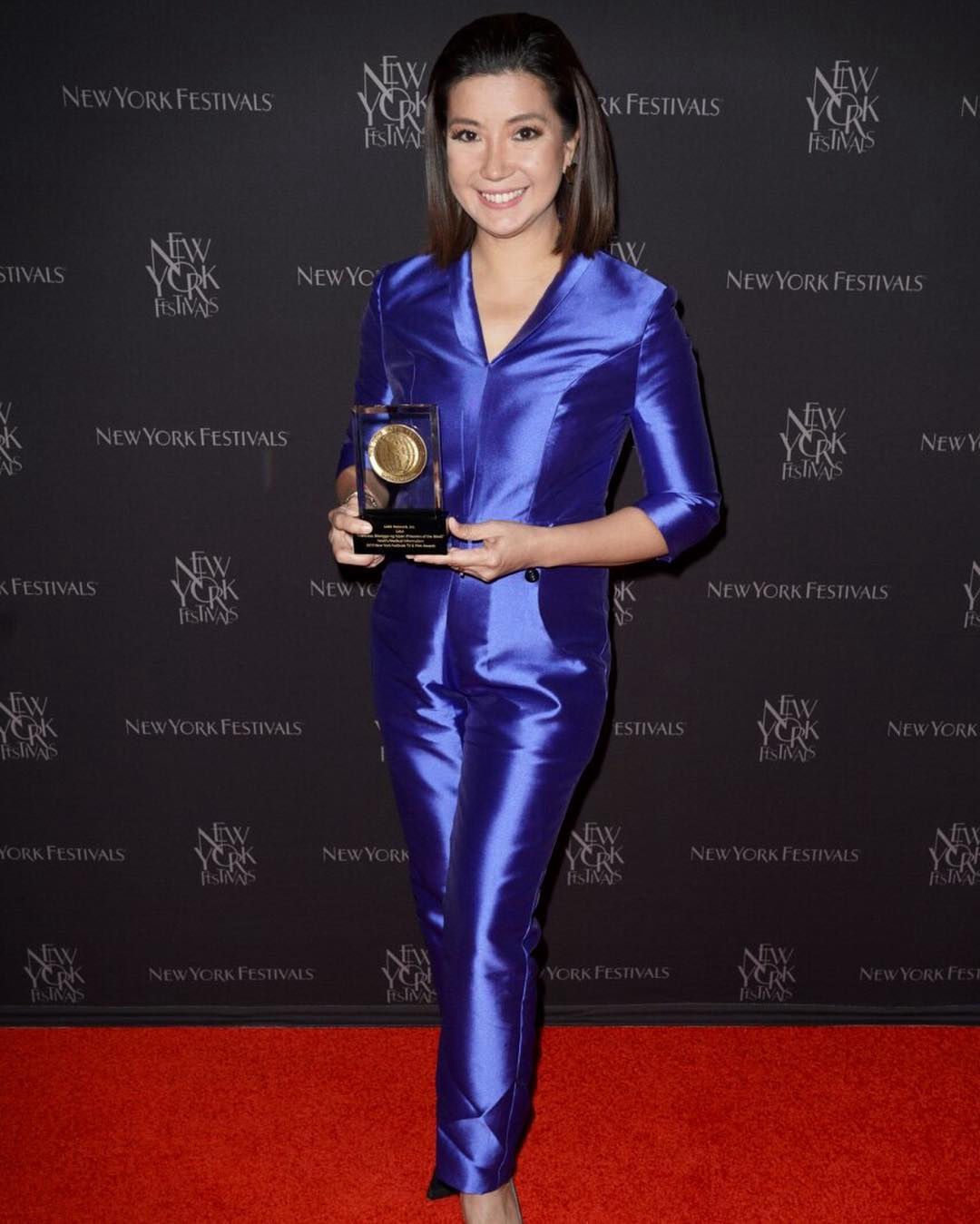

Kara David has won numerous international awards for her work on I-Witness.

Now, Kara’s foundation offers over 25 scholars education. They’ve helped generations of children who have set out to become teachers, accountants, seamen among many others.

Kara remembers two women who helped her understand how important the act of passing her blessings forward was. In the past, Mel Tiangco told her, “When you have more than enough, it’s time to give back,” and Kara’s mom, activist Karina Constantino David, would tell her, “If you want something to last, give it to others.”

Even in Project Malasakit, Kara’s eyes continue to be opened. “We have scholars in Mindanao who stopped their schooling because they had to be married off at a very young age. We have scholars whose education was stopped by their parents because they prioritized their sons,” Kara said.

“There are those who got pregnant too early, those who were married off early, there are those who are asked to take care of their siblings and they had to stop their schooling, and there are those who are abused. We have scholars that grew up with the abuses on the streets, who entered prostitution.”

She added, “And I saw that in many of our scholars, especially our female scholars, that once they were given the opportunity, once you offered help, once you invested in them, they won’t let you down.”

“Look at her strengths. And I’ve been so blessed because my family, my school, my workplace never looked at my gender. They looked at my capabilities. They didn’t say, ‘She’s a woman. She might not be capable.’ They say, ‘She can do it because she’s proven she can.’”

With everything Kara has accomplished, she continues to pay it forward with integrity and compassion. She has also set out to become a teacher not only for the University of the Philippines but also to anyone interested in journalism through her own Youtube channel.

Kara David said, “I guess if there’s any message I have for aspiring journalists, you can’t have it in just one take. You’ll go through so much before you get your dream but don’t be discouraged because the journey, the path to your dream, that’s what’s going to teach you so what you aspire for will be more beautiful.”

Tan Fajardo is a fighter — not because she wears a pristine white uniform as a jiu jitsu athlete who knows all the ways to take someone to the ground.

She is a fighter because she has been thrown flat on her back far more than she could count. And without fail, she pushes herself up, brushes the dust off her shoulders, and plants herself firmly on the ground, her resilience and determination her own body’s gravity.

Tan was 25 years old and had just started working as a nurse when she lost her leg in a series of events nobody saw coming.

It was 2009 and she had just started working as a nurse. At a wedding, she experienced leg cramps. “I was brought to the hospital where I was only treated for muscle strain. And then it progressed.”

After a while, she could barely stand or walk because of how much the pain grew. She was immediately brought to the hospital and was initially diagnosed with myofascial pain syndrome, a chronic pain disorder. Then doctors found blood clots in her body and soon afterwards, she was diagnosed with vasculitis, an inflammation of the blood vessels.

“It took a lot of diagnostic tests to get an actual diagnosis since it was uncommon to have a complicated blood-clotting problem for a young and active person such as myself,” Tan said. After her diagnosis, Tad had to transfer from her hospital in Baguio to one in Manila where she had to stay for three months and undergo over 10 operations.

At first, Tan was in complete denial. No, she told herself, she wasn’t going to lose her leg.

In the ICU for a week, her doctor would ask her to move her toes.

And then one day, she couldn’t move them.

“I couldn't control it anymore and it was turning black already. That's when I started getting the feeling that I'm really gonna lose my leg. And then, the doctors told me that they have to amputate already,” Tan recalled.

Even after receiving the news, Tan knew she wasn’t ready to lose her leg yet. She requested to have it removed after Valentine’s Day so she could at least celebrate the holiday.

“The night before, that's when I started crying and I was angry. I was really angry. ‘Why me, why my leg, why at this age?’ I was still 25,” Tan said. “After that, when the leg got amputated, it was weird but I was already okay because the pain I felt disappeared. And I had acceptance right after. Well, I thought I did.”

Tan Fajardo after her amputation in 2009.

After Tan’s leg was amputated, she jumped right back to living her life to the best she could: she started helping in her family business since she couldn’t work as a nurse anymore. She started going to prosthetic school so she could learn how to adjust her own prosthetics and help other people. She did charity works, and she even began swimming.

“I really thought I was doing okay,” Tan said. “But I was wrong.”

Shortly after, Tan found her way to the dangerous path of substance abuse and self-harm. She was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and anxiety soon afterwards.

“I actually felt like a prisoner held by my illness and my past mistakes. I really completely felt like a prisoner,” Tan added.

She was admitted back in the hospital for detox. “When I was in the hospital, I had so much frustration. I was really mad at the world, at myself. I was angry at everything. I thought to myself, ‘Why did this have to happen to me?’”

Along the way, Tan shared she experienced more losses. She and her partner broke up a few months after she lost her leg. Friends and loved ones kept her at a distance after she fell into the hole of substance abuse.

As though things couldn’t get worse, while she was recovering from her substance abuse, in 2014, Tan was also diagnosed with Lupus.

“I was complaining again of leg pains so they ran all the diagnostic tests. And then, that's when they found out I had Lupus,” she said.

She was attending prosthetics school, but she had to stop because it triggered her new-found diagnosis.

“It looked like there really was a different plan for me that I had to stop because the stress and load the school required per semester would definitely trigger my Lupus,” she said. “I lost another career path. I had to stop sports.”

Tan Fajardo shares how she has overcome all the challenges that have come her way.

She started going to an outpatient rehabilitation program for her substance abuse problem. After she finished, Tan enrolled in the Center of Family Ministries to become a counsellor “and help others who went through the same problems as I did.”

While she didn’t finish the course, Tan said “it helped me with myself. The journals the priests and counsellors made us do, helped bring out the things that I hid from my own self, things I felt inside.”

Add her rehab experience to the mix, and Tan realized that everything “was actually able to help my relationship with my family, my relationship with myself. It ended up being a good thing that happened.”

What really changed everything for her though was jiu jitsu. She came across it, and piqueing her interest, she decided to try it out on the mat.

Her first experience, however, could not have started out worse as it did.

“I was really scared — of the people, of judgement since I was the only amputee there, and the fact that I was a woman [in] a male dominated sport,” Tan said. “I was embarrassed because I was really still insecure about myself. And I’m an amputee, what would the employee and staff think?”

But the people in DEFTAC, Makati, a center for martial arts, were very accommodating that Tan easily adjusted. “They helped me learn how to move with my limitations. The coach there also really put his focus on me even if it’s one-on-one already which really helped me boost my self-esteem,” Tan said.

Jiu jitsu, she said, has helped her physically, emotionally and mentally.

“Whenever I have problems, when I'm stressed or I feel down, I go to jiu-jitsu. I go to class and then after a few rolls and after the lesson, I actually feel better about myself,” Tan said.

Apart from keeping her sane, rewiring her brain, and helping her get “my mind off the things that are stressing me out whether that would be work or other things,” jiu jitsu has also opened doors for Tan.

“I gained new friends, new love and then I was introduced to other sports,” she said, explaining she gained her confidence back not just to try new sports like wall climbing, swimming and shooting but form TheseAbledPH, an organization that aims to help amputees challenge their limitations through sports.

The name, Tan explains, is an onomatopoeic play on “disabled,” so that members are able to positively change the label they give themselves.

Tan Fajardo formed an organization called TheseAbledPh which aims to help amputees challenge their limitations through sports.

Although she’s at a better standpoint in life, Tan admits to still facing struggles as an amputee on a daily basis.

“Sometimes, I cannot deny the fact that I’m still limited. Now, with just walking I get tired on a day-to-day basis that I have to stop and then rest for a while, wait for the pain to go away and then start walking again,” she said.

“So instead of finishing so much like before, it’s lesser now. So I had to schedule everything...so I can maximize and I wouldn’t be frustrated with myself.”

She adds, “Being a PWD (Person With Disabilities) in the Philippines is quite difficult especially with access ramps, buildings with no elevators. It's difficult for us to adapt sometimes because we’re not given the same attention. Sometimes, they think that it’s okay, that we can do it or whatever but they don’t know the struggle of, like, as simple as walking.”

At 36 years old, Tan is an HR Manager at an international corporation. She is a PWD advocate, an athlete, and so much more.

“Before I lost my leg, I loved dressing up. I was always in heels, sandals, skirts. And then after I lost my leg, it took a while before I started regaining that confidence again. I would always hide my leg, I would always want to be wearing pants or long dresses just to be able to hide it. But then, one day, it just hit me ‘I can’t do anything about it at all,’” Tan said. “I just really have to accept it.”

Tan has gotten quite confident that of the two types of prosthetics she has -- one that looks like a real body part, and the other that looks like metal — she prefers using the latter more often. “I don't feel ashamed anymore even when people stare at me. It feels OK.”

According to Tan, the support from her family and her boyfriend has helped her so much.

“My nephews would always be curious about my leg. So whenever I'm home in Baguio, they would always call me, ‘Oh, my Tita Tan's a robot.’ It makes me feel...It's funny actually. It's funny and cute in a way. And it makes me feel accepted even if I'm different,” Tan said.

“I feel empowered when I show my vulnerability. Like now, sharing my stories of triumph and failures and in the hopes that somebody else would also learned from my mistakes or from the lesson that I've learned,” Tan said. “Never be afraid to be yourself, to do more and be more and never be afraid of the failure and change because that's how you will learn to do, adapt and grow.”

“For a long time, I wanted to pursue an academic path. I wanted to be a lawyer like my dad because that's what I saw growing up. But I think it was a matter of always just believing what people said I could do. Because I was the smart one, I was never the pretty one. At school there were those labels,” said Erianne Salazar, a commercial model and makeup artist.

“For some reason, people didn't believe that you could be both. For example, ‘Oh Er? she can be a lawyer, but not a model, makeup artist. Never, because she looks like this, she's heavy, she's kulot, she's morena, all of these things,’” Erianne said.

At home, Erianne never felt any kind of pressure to change the way she was, morena skin, curly hair, and all. It was always about acceptance and love.

“But as soon as I started school and I was there with other kids — there, they called me all the animals they could think of. They called me monkey because I was morena, pig, all these different things, they’ve already called me.”

She added, “Then, it just snowballed from my appearance to everything else. If I accidentally fell, they’d just laugh.”

As if that wasn’t enough, her own teachers would make fun of her acne, something she’s been living with for the past 15 years.

“At school, you’re not allowed to wear makeup so everything is seen and I was forced to cover it up because even my teachers made fun of me. They said I looked like pinipig, that it was shedding. I looked like a zombie, whatever,” Erianne said.

It was so hard for Erianne to hear and deal with criticisms on a daily basis that at just seven years old, Erianne had her hair straightened.

“No 7-year old should have to think about these things,” the model began. “Like, ‘Ay, I have curly hair. I have to straighten my hair because I’d be bullied when I’d get to school.’”

”I was always self-conscious that everytime I would be sitting down, I’d cover my stomach with my hand because they’d always say I was fat, I had a lot of flabs.”

It didn’t help that while growing up, skin care products were all catered to make people “whiter.”

“That was my experience,” Erianne said. “Aside from the perpetuation of that beauty standard, there were all these treatments everywhere to ‘help you solve the problem,’ because you are a problem. That was like its message.”

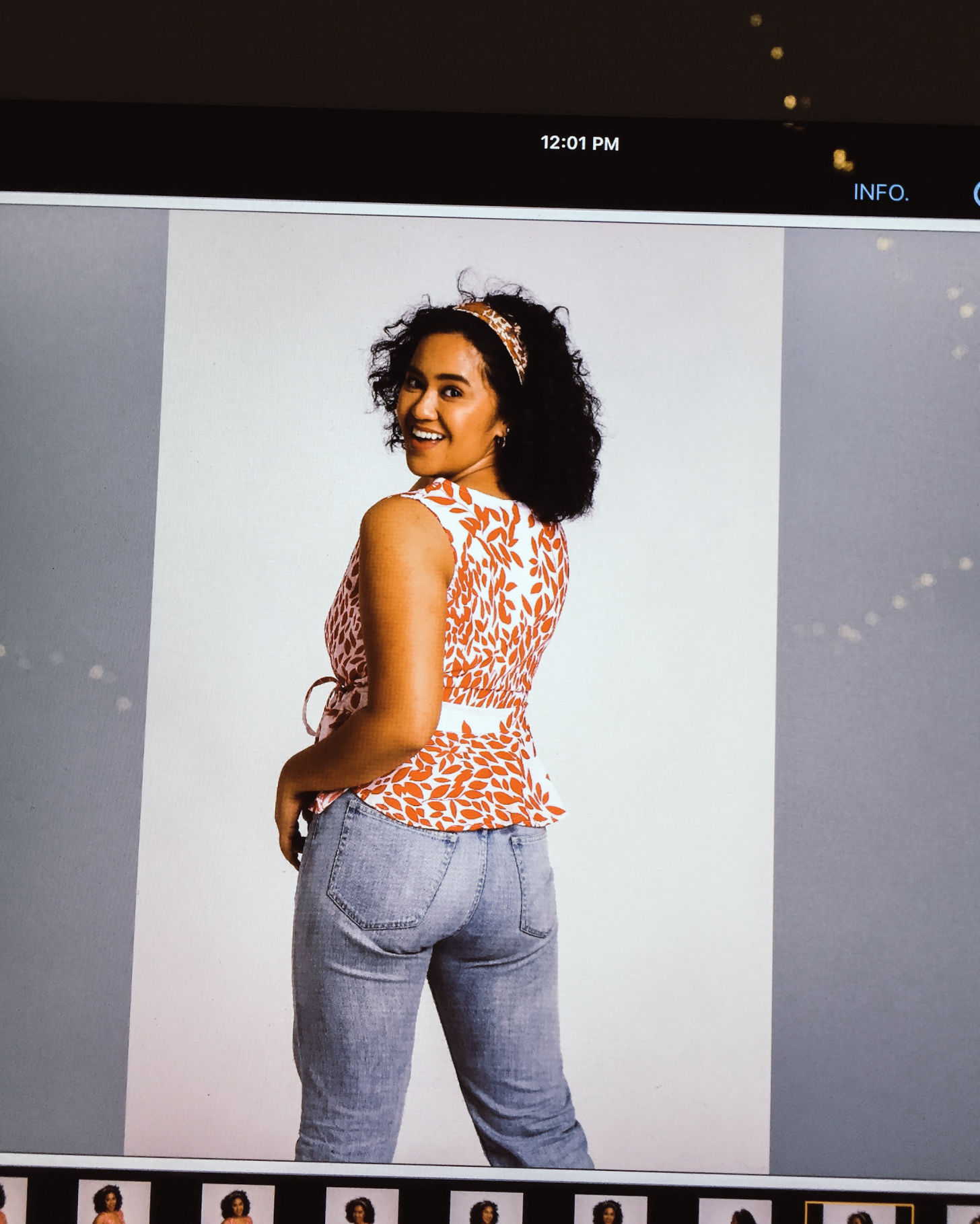

Growing up, Erianne Salazar was all too familiar with the harsh beauty standards in the Philippines.

All those years, Erianne said had no one she could talk to about the bullying she endured. Neither did she have anyone tell her that she was perfect just the way she is.

She kept a journal wher he wrote everything, but when “you’re a child and you don’t know how to verbalize all these things to other people because you’re scared,” she says.

Erianne ended up with a bad habit of picking her face to the point that she’d find herself in a trance-like behavior and wake up with a bloody face.

“I wouldn't notice it until it was over,” she recalled. “It was like a trance. It was like a hypnotic trance wherein I will start the ritual of it, I’ll get something to pick my face with. I didn’t care if it was dirty. I didn’t care if it was an odd thing like a needle or a hairpin or my nails or whatever it was.”

“I will scan my face. I’ll look for the bumps and I’d pop them one by one. I would spend hours, hunched over a mirror and I’d just do that to the spots,” Erianne added. “And then, I’d just snap out if it and wake up. My back would hurt since I’d been hunched over for so long, my face would be bloody and the spots would be sore, making it worse than what it looked like before. I used to also peel my cuticles until it bled.”

“A person can only take so much and all of these compounded experiences put together — it was heavy.”

It got to a point where Erianne slept for 20 hours a day and hardly took care of herself. “I only woke up to drink water or pee. I didn’t even want to shower anymore. I did not want to change my clothes,” she said.

“I did not care that I was growing acne on my body also because i already had it on my face and all of this sweat,” Erianne said. “Then, I realized to myself, ‘Who is this? This is not me. What am I doing to myself? I’m no longer taking care of myself.’

She was already finishing college then, on her last semester in the University of the Philippines “but I really couldn’t take it anymore.”

“I couldn’t force it anymore. It was there already. It was past breaking point. It was already at its limit. I couldn’t push it back anymore or else I’ll break. You bend and then you break, and it was already at its most bent point. And then, I really had to say, ‘Help. I’m drowning,” she said.

With her family in Baguio, Erianne called her parents to tell them something was wrong. “I need your help,” she narrated. That was the first time she ever told her family of her problems.

“I went home to Baguio with nothing but the clothes on my back. I left everything behind and came home. And that's when we started looking for doctors. We tried to call family friends who had experiences with mental health issues so we can get on this path of getting better.”

Erianne Salazar talks about how she battled through issues before finally forging a career in the beauty industry.

Erianne ended up getting delayed for four years in college, but she was also able to take her time to get better, something she couldn’t do before.

Throughout her journey of healing, Erianne revealed that makeup really was one of the things that gave her solace and comfort.

“I’ve always loved doing my nails, my hair, my makeup and all of these things,” Erianne said. “And my love for make up became deeper because I have something like an OCD and I pick on my face.”

That’s one of the reasons that Erianne now always has nail extensions or gel manicure to make her nails more blunt so she couldn’t scratch or pick on her face.

“Until now actually, it's still struggle that I continue to try to overcome pero it's really a lot better now than it was before, for sure,” Erianne said. What really helped her, she said, was her love for makeup.

“I needed to keep my hands busy so I don't hurt myself and that's where I started really playing with make up, spending hours and hours putting on make up, taking it off, putting it on again because it feels empowering to be able to do something with your hands that doesn't hurt you,” she said.

Despite the horrible things thrown in Erianne’s way, she did not stand back.

In 2017, Erianne joined the Nyx Face Awards, and took her first step at a modelling career.

“I just randomly entered on the last day of submission,” she said, looking for something to be excited about. “I was still having suicidal thoughts, [dealing with] low self-esteem, self perceptions. But for the sake of it, because I was looking for something to make me feel something even if it's nervousness or kaba or anything, whatever. I saw it and I joined.”

There, Erianne said that she met so many people in the beauty community who were beyond kind and inclusive. They’d tell her that they were connected with other known figures in the industry and that they’d be more than willing to introduce her to them.

Soon, Erianne was cast in a lot of roles because of what she looked like.

“I already have some roles and some jobs that cast me because of my features—curly hair, Pinay-looking, brown skin, all these things,” Erianne said.

Erianne Salazar is proud to represent women who looked just like her.

Though the beauty industry has gotten better and has become much more inclusive than before, Erianne said it still has a long way to go.

But for now, she feels proud for being able to represent women who look just like her: curly haired, brown skin, and all.

“I am able to put myself out there to represent women who look like me because growing up I didn't have that. It was always lighter skinned, thin straight haired women on the TVs and billboards, right? There was nobody who looked like me and that's why I was bullied because there was this stigma,” she said.

Erianne is fearless in telling her story. From making sure no woman is made to feel ugly for looking the way they do, to sharing her mental health struggles, the 25-year-old model and makeup artist considers boldly narrating her story, as among her greatest achievements.

“That's where I see that it was worth it and that I will keep doing it again for as long as it's necessary,” she said. “I consider it an achievement if I may say so. That sharing my story so far is helping others broaden their definitions of themselves more than being limited to what was defined for them. I think that's very important.”

If there was anything she could tell others, Erianne said, “Make it a priority to be kind to yourself because the world can only be get so cruel. So if we can be alone with ourselves and be at peace with what we tell ourselves at night, that would make all the difference. Really one of the biggest things that I advocate for is self-compassion more than self-care.”

Miss Trans Global 2020 Mela Hajiban knew her truth.

It resounded deep within her, no matter how many times people tried to bend it, change it, erase it, or deny it. She has held it dearly, because she has journeyed long and hard to confront it.

“Growing up, my generation didn't know about Sexual Orientation Gender Identity and Expression,” Mela said. “Growing up, we only knew girl, boy, gay and lesbian — that was the nature of gender and sexuality I grew up to know.”

Mela knew from an early age that she was different. After watching her first ever Miss Universe pageant, she immediately saw herself a queen.

“I was four when I first watched it and then I got fascinated with the idea of being on stage, more importantly being a queen,” Mela said.

Not knowing the full spectrum, Mela came out as a gay man when she was a teenager. “I thought I was just simply a flamboyant gay guy who's very feminine,” she said.

In 2013, Mela encountered the word “transgender” and was quickly amazed “that there was such a thing and there was that kind of sexuality.”

That’s when she started reflecting on who she really was, Mela said. “It was a journey of push and pull, push and pull. Because I know that there are prejudices and there are stereotypes when a person who was born male comes out as a woman.”

Well aware and scared of the abuses, violence, and discrimination that transwomen face everyday, Mela’s need to embrace that side of herself grew only stronger. “I needed to be strong enough to be able to showcase who I really am. So it was a long process,” she said.

Mela underwent a three-year long discernment period to get to know who she really was. “That was a tough journey to be in because I know that there was a woman inside of me but she was so afraid to come out because she didn't know if she'll be respected. What will happen to her career? Will she even have a career to go back to? Or what if her options to grow and live her life become limited?”

Above all, Mela said, she was afraid for her parents. “Will they accept me? They already accepted me as a gay guy. What if I came out as a woman? And that will be a different case.”

It was a long and gruelling process, but when a transsister told her she should come first and she should be at the center of her decision, it became clear and final. “In the end, it will always be you who will decide who you want to be, where you want to go and how you want to live your life regardless of what other people would tell you. You have to ask yourself, ‘What does your heart tell you?’”

Mela Habijan's parents were proud of her beauty pageant win.

Holding on to that dearly led Mela to begin her transition both socially and medically.

She admitted she felt scared since she was 30 years old already at that time.

“In the language of transwomen, the younger you have your gender affirmation, your hormone therapy or its most common name, HRT, the easier you are to become ‘softer.’ There’s a language of softness, of being feminine,” Mela said. But she realized that it didn’t really matter how soft or feminine she looked, because her womanhood went beyond the physical.

“I don't need to look like that patriarchal concept of what a woman is but rather I want to define my own womanhood,” Mela said. “Womanhood for me is a sense of character I live by. I should be a woman of power. Meaning to say, I take control over my life…A woman should just know how to live her life. A woman is in control and will always be decisive and will always navigate her life to where she wants to lead.”

She added, “So right now, I'm happy with how I look. If I can look ‘softer,’ happy. But it doesn't matter how soft or how feminine I look because what matters most is how I feel inside. And taking a hard look at myself right now, on the screen or in front of the mirror, I can tell the world, ‘I am a woman enough.’”

Through the years, Mela continued living her truth and representing her community. In 2016, she ran for city councillor in Marikina openly as a member of the LGBTQ+ community. In 2018, she took on an acting role for GMA Network’s drama series “Asawa Ko, Karibal Ko.” It soon led to appearances in other projects like “The Better Woman” and “Magpakailanman” — huge opportunities in helping people understand what being a trans woman meant.

“It's an opportunity for me to take on transgender roles to show people what trans really means, what a transgender person can really do, right?” Mela said. “Seeing yourself on TV, just seeing your talents and the definition of who you are as a person, that’s already a big deal.”

For Mela Habijan, her journey has been about the opportunity to represent and be visible.

By 2020, Mela became queen. She won the title of Miss Trans Global that year, with her family holding her hand and cheering her on. “It wasn't just me competing,” she said. “It was the Habijans along the way, in every single step of the competition.”

And when she was announced the winner, Mela was a brimful of happiness —not just because she won—but because her family was there celebrating her victory.

“That’s the ultimate gift that a transgender person or an LGBTQIA person could get - family's love and support,” Mela said. “It’s such a big deal that you are loved and accepted within your own home because even if the world treats you poorly, you will always have a place you can go back to, to freely laugh and cry at, and be who you really are. And they will embrace you whole-heartedly without any question.”

Although Mela and her family were able to fully accept and completely celebrate who she was inside and out, the world, on the other hand, still had a long way to go.

There are still micro-aggressions that continue to persist — “’You finally look like a woman. You look like a real woman.’ We also have those who say upfront, ‘You’re not a woman’” — and even within the community, Mela says there are different beliefs on softness and femininity.

Despite the discrimination she has endured, Mela is unafraid of telling her truth—something she has fought long and hard to have its rightful place under the sun. Mela looks in the mirror, she sees a strong, beautiful woman staring back unafraid to tell her truth to the world.

“I continue to write, I continue to speak, I continue to communicate so that people and women like me will be able to transcend boundaries that hinder us from being who we are,” Mela said.

She added, “I am willing to be a part of that venture in which they [youth] can have a Philippine society who will fully accept them. And where are we at this point in the fight? We’re still far but we’ll get there.”

Dr. Naheeda Mustofa has known Islam all of her life. Although at times feared, and misunderstood, it has led and guided her through all her nights and days.

Born and raised in Saudi Arabia to a Moro dad from Bangsamoro and a Batangueno mom, Naheeda was introduced to Islam on the day she was born.

“I grew up there for at least 9 to 10 years so I was able to appreciate Mecca, Medina, Hajj, the pilgrimage,” she said. “Every now and then, you can hear the prayer. Of course, the five times a day azan during the day.” In Saudi, Naheeda said, they practiced Islam religiously.

When they went home to Balayan, Batangas, however, “we really adjusted. We had to adjust to the environment.”

Other things soon preoccupied her, like medicine. “My mom really influenced me because my mom is a nurse. Day in, day out I’d see some of her patients coming into our house, and she would check them for free,” Naheeda said.

But as Naheeda pursued medicine, so too did Islam pursue her.

“There were gimmicks, outing with friends, they’d invite you. Later on, I got triggered to practice and wear my hijab because in one outing — I was able to join one outing —I realized, ‘Hey, it’s not happy.’”

She felt a shift within herself. “You can go to a place, there’s music, there’s drinking sessions, but I don’t drink. But the way I saw it, it’s so temporary, so fleeting.”

Naheeda shared that she started studying Islam more intently and finally decided to devote herself to it and practice its teachings.

It wasn’t always smooth sailing, though. When Naheeda began embracing her religion, she admitted to having a hard time leaving the house with her hijab on. “I was struggling that time especially going out of the house. I couldn’t do it. I said, I’d look at myself in the mirror, and I couldn’t stand looking at my face with a wrap around my head.”

It helped that she had a supportive environment. Her classmates in med school, for instance, were very supportive and understanding of her practice. “I had friends who have knowledge about the faith, who understood the faith.”

“It’s always between you and the Lord,” Naheeda said. “It’s how you want to serve or please your God. I said to myself, ‘Okay, I wanted to practice it during med school.’ And that was way back in 2000. So from 2000 I started wearing belo. This is my 21st year wearing a hijab.”

Faith has been part of the journey for Dr. Naheeda Mustofa.

In fact, being a Muslim, Naheeda said, has guided her during her own practice with medicine.

As a Muslim doctor and clinical nutrition physician, Naheeda’s calling to help other people has also become an act of serving God. Whenever she encounters a patient, it becomes important for her to bless the patient and the service she’ll do. She would even say prayers in her mind when attending her patients and say “In the name of God” or “Bismillah” when she’d insert an IV.

“We have this sense of responsibility also towards our community that it’s not just about finishing medicine, passing the board, doing your clinic, and earning. It’s not just about practicing your profession, getting rich or getting credit for what you do. It’s more on how we can collaborate to serve the community. Whether Muslim or non-Muslim it should also be the same,” Naheeda said.

She added, “And it’s how to please Allah. So if you’re doing it, you should make sure it’s supposed to be directed towards making the Maker happy.”

Not everyone, however, understands what Islam is, especially after the 9-11 attack and the Abu Sayaff conflict.

“I also had a time, like, ‘What do I do? Should I remove it [hijab] for awhile? Should I get rid of it for now? Because I might take a ride in a jeep and somebody could just suddenly push me,” Naheeda said.

“I can’t deny that I had those episodes where my fears and worries that I might have a hard time practicing my faith mixed. But Alhamdullilah, it’s like God said, ‘If you’re doing it for me, if you’re doing this to serve God, just one step and He’ll take all the steps for you.’”

Slowly, the tension dissipated. “Eventually, you just have to be yourself.”

For Dr. Naheeda Mustofa, her medical practice has been guided by faith.

Even until now, she would see hesitation and even confusion in her patients’ eyes whenever they see her in a hijab.

“I observe that there’s fear, it’s really more on fear. It’s like survival instinct, right? So you have to combat that fear within yourself and ask ourselves, ‘Wait, how is this person?’ Let’s ask the person we’re in front of how they are or the person beside us, before we worry about ourselves,” Naheeda said.

“It’s more on redirecting your energy towards how you can make someone happy or how you can make someone calm…They couldn’t find a reason why they should be afraid. So my worry was more on that they’d get scared.”

In Islam, Naheeda said that they also believe in Virgin Mary, in Jesus and that they were sent by a higher God named Allah. And Jesus, she shared, always taught about love and compassion.

“That’s why I really don’t believe in religions that would advocate for fear because Islam is peace,” she said. “You cannot advocate peace if you’re not peaceful yourself, right? As a physician, I think it helps a lot because you really put your love for your patient first.”

Amid the pandemic, Naheeda’s clinic continues its operations and Naheeda continues serving other people — beyond her profession. She has also opened a kitchen inside her clinic so as to serve her patients the proper healthy food incorporated in their medical plan.

Like a true woman for others, Naheeda has also found a way to use her being a Muslim to brighten the day of other people.

“I think we can say that the achievements I was able to achieve, whether it may be becoming a doctor, or specializing, or taking up masters, for example, is just part of the blessing from God,” Naheeda said. “So I think the greatest achievement that we should focus or that we should define in our lives is really achieving something towards service, serving God.”

When Rabiya Mateo emerged the winner of Miss Universe Philippines, she took her spot under the beaming sun, a place she fought for all her life.

She paved the way with her own blood, sweat and tears, motivated by her own determination to give her loved ones a better life.

Born to an Indian father who left the family when she was just little, the Iloilo beauty queen only had her mom and her brother growing up.

“I had my humble beginnings. You’ve hear stories that I used to just sleep on a banig. There were also moments that they’d cut off our electricity,” Rabiya said. “My doormates had foams for a bed, and I was proud to have a banig to sleep on. During those times they never made me feel like, ‘Oh, you’re so pitiful!’”

Growing up with a single mother, Rabiya promised herself that she would give herself and her family a better life.

“I really thought before that I didn’t have hope in life. I thought we’d be poor forever but my mom told me, ‘Study, anak, because that will be your ticket to rise up and help other people.’ And I believed her. And it really happened,” Rabiya said.

After getting a scholarship, Rabiya would work on the side to earn for her family.

“I experienced studying and working as a model at the same time. For example, I have an exam at 3 p.m. but I have a project at 5 p.m. I’d take the exam wearing makeup. I still continued studying because I don’t want to let myself get distracted by my work as a model,” she said. “I thought to myself that I could do them simultaneously because I need the money and at the same time I need to excel in my studies to maintain my scholarship.”

“I always got rejected because they’d tell me my qualifications don’t match with what they were looking for. I asked myself how I could save up to take my board exam,” Rabiya said. “I even applied as a model who’d give out flyers. I did everything.”

Her mother, said Rabiya, always inspired her to do well in her studies.

“I saw how hard Mama worked just to help me out. There were nights she’d wash my uniform because I only had two so it was wash and wear. I’d see her and I’d tell her, ‘Ma, let me wash those,’ but she’d say, ‘Let me, anak, just study there. Do your duty as a student. I’ll do my duty as your mother.’”

Rabiya Mateo was inspired growing up by her single mother.

The journey leading to Miss Universe Philippines happened in the most extraordinary of ways.

Rabiya was first inspired to join beauty pageants when Venus Raj won the Binibining Pilipinas title back in 2010. She found similarities with Venus: They both grew up without a father. They were both from the provinces. They were both morena, a quality that made her feel less than beautiful.

She would receive comments from people who said that she could’ve been beautiful if only she was fairer. “And for a moment, I believed them. I was obsessed with whitening my skin,” Rabiya said. “Everytime I looked in the mirror, I hated myself because I told myself that what I saw wasn’t deemed as beautiful by others. I want to be accepted by this society. I want people to love me. I want people to appreciate me even better.”

When Venus won, “I was inspired by her to actually do beauty pageants because the platform is different, the audience who listens to you is different but it took a lot of time and courage actually to put my feet forward and try pageantry because it was frightening,” she said.

She started joining school pageants at at the age of 15 but never won. “I told myself that maybe pageantry is not for me. Imagine this is just a school pageant, and I couldn’t even win at that, what more a local one, a national one,” the beauty queen said.

Rabiya represented the college of physical therapy for a sportsfest, and even there, she didn’t bring home the crown. She started to lay low in the pageantry scene since the losses she felt was still heartbreaking to say the least.

“I thought before it was a sign that it wasn’t meant for you but failure is part of success. It’s like a stepping stone for you to reach that point of victory,” Rabiya said.

She was afraid to try again but her mom reminded her that it was her dream and she should try it. At 23, just after college, she joined Miss Iloilo.

“Maybe it was beginner's luck, I won. And again, first national pageant I won maybe because I really prepared for it. It’s not just about destiny. It takes a lot of hardwork and determination to be there,” Rabiya said.

According to Rabiya, she only had a week’s worth of preparation for the Miss Universe Philippines after becoming Miss Iloilo.

“I was thinking, ‘Okay this is really it. This is my dream.’ I told myself before that just being able to join in a national beauty pageant was enough for me. I was okay with that already,” she added.

Rabiya also didn’t hide the fact that she was fangirling when she saw the other candidates for the Miss Universe Philippines pageant.

“They were all so beautiful! They were all good, and before I’d just be able to watch them on TV but now, I’m among them,” she said.

Rabiya added, “During that moment, I felt like I was so small because I didn’t have the experience...I don’t have my own core team during that time but I told myself that even if this is all I have, I’m going to make the best out of it and I’m really going to give it a fight.”

Rabiya Mateo's journey to the top has been long but fulfilling.

In October 2020, Rabiya became Miss Universe Philippines.

Rabiya couldn’t believe it when she won the crown during the watch party.

“The euphoria I felt--I felt so happy and I felt good because all of your sacrifices, all of the moments you doubted yourself came rushing back and I said to myself that it can be done. It can be done as long as you brace and strengthen yourself.”

But Rabiya’s win was soon clouded with controversies when a candidate accused the pageant of cheating.

“When I won, a lot of people were starting to bash me because of the controversies but whoever you were in the past, it’s going to have a great impact to who you are now, and a lot of people really defended me because they know me as a person,” Rabiya said.

Rabiya has since denied this, along with other Miss Universe Philippines officials, and Rabiya continued to succeed and became famous almost overnight.

“The fame almost happened overnight, as if in a blink of an eye. Everybody knew my name and I’m not used to that,” Rabiya said. “Whenever I go out, there are people asking for pictures. Even until now, I think to myself, ‘Oh right, I’m the Miss Universe Philippines,’ and they look at me as a source of inspiration that’s why I should never fail them.”

She added, “There are also moments that sometimes I forget to be a normal person because you need to be perfect all the time. You need to look good. Your clothes need to look good because if not, you’ll fail people’s expectations and that’s the hardest part. Sometimes, the beauty queens, we are hindered to be our authentic selves because we mold to a certain standard the public, our fans, have on us.”

She added, “We know that Filipino fans, they really love beauty pageants. They can be the best, but they can also be the worst fans that’s why there’s a lot of pressure on the candidate, but again just think that this is for our country, that you’re doing this to give pride and honor to the Philippines. It’s all about perspective because the right mindset will separate you from the rest.”

Undergoing trainings left and right, Rabiya is set to bring her best self to the stage. She’s also two months away from competing in the Miss Universe competition.

“It’s not just the test of your physical endurance. It's also a test of your mental stability because it's always mind over matter. If you keep thinking to yourself that you don’t have any rest, that you’re really tired, you’ll really get defeated easily,” she said. “But if you think that you have to do this because you need to improve yourself, you need to do it for your country, then you’ll really have the energy to do better in your activities and trainings.”

With a powerful crown on her head, Rabiya encouraged all women to do what brings them happiness and to widen their horizons.

“There’s so much power in us that we don’t realize yet. A woman can be an educator, a mother, most especially a woman can lead her nation,” the Miss Universe Philippines 2020 titleholder said “So I hope when we wake up in the morning we realize that we live in a much humane and peaceful world because a woman is doing her work.”

In February, President Rodrigo Duterte said in one of his speeches that women are not cut out to be president of the country.

“The emotional setup of a woman and a man is totally different,” the President said.

University of the Philippines Center for Women’s and Gender Rights Director Nathalie Africa-Verceles takes issue with the statement.

“No one will ever say men cannot lead, right? Never,” she said, noting how countries who performed the best in terms of managing the COVID-19 pandemic are those led by women such as Jacinda Ardem of New Zealand and Tsai Ing-wen of Taiwan.

“I always say that it’s all those characteristics considered as feminine and are ascribed to women by society as well as women being socialized into these characteristics — being caring compassionate, empathetic, nurturing, emotional, sensitive, patient, understanding— it’s all these feminine characteristics that have actually helped women leaders respond well to the pandemic with respect to their constituents,” Africa-Verceles said.

Sociologist and UP instructor Athena Presto said gender biases continue because there are still those who think that men and women are inherently different and think that “one characterization of a certain gender is necessarily weaker than the other.”

She said, “Both men and women can be emotional and we’ve seen a lot of male politicians cry on national television and yet we still have the same people saying that women can’t lead because they’re too emotional so there’s this disconnect.”

Powerful institutions such as religion and schools also play a big part in forming the notion that men and women are “different.”

“Do you realize how perverse it is that everytime we have exercises in Grade 2, 3, 4, it was always gender biased? So for example, we’ve all experienced the matching type questions, match the skirt for the girls, washing the dishes, getting wood,” she said. “That’s a very perverse way of inculcating in the minds of you of young people different gender norms.”

Media also plays a powerful part in shaping minds, especially when advertisements categorize which product should be advertised by which gender.

“So everywhere you look everything is gendered. Even our law is very much gendered,” Presto said. “If you look at them they can still carry different gender stereotyping, like for example, we have the expanded maternity leave...We didn't have it mandatory to have like paternity leave in this country and what does that say? That says that the law still thinks of child-bearing and childcare as inherently women’s job.”

According to the Global Gender Gap Report 2020, the Philippines is the most gender equal country in Asia, although it dropped eight notches and only placed 16th among 153 countries.

Women outnumbered men in senior and leadership roles, closing 80% of the labor force gap. It also closed its health and educational attainment gaps as more women are enrolled in secondary and tertiary education.

However, the political empowerment gap has widened as there is significantly lower female representation in Duterte’s Cabinet.

Although the Philippines is among the top 20 gender-equal countries, the reality is different, said the experts.

“We should take those Global Gender Gap Report rankings, all rankings, with a grain of salt because they don’t really adequately reflect the situation of the vast majority of Filipino women because it intersects with class. There are still a lot who are poor,” Africa-Verceles said.

“If you look at all the standards and parameters that we have, the Philippines is not a sexist country...It’s different if you’re really here and you look around yourself. Opening up of opportunities for women are really not given importance,” Presto said.

A lot of women, Presto said, are part of the informal economy as they spearhead household work such as doing the laundry and cleaning houses.

“So our policies don’t reach them because they’re not tagged formally speaking and it’s so hard for our lawmakers to make laws and to craft policies addressing ‘invisible people,’” she added.

That’s why, Africa-Verceles said, it’s important for everyone to continue to raise critical awareness about the “unequal gender relations about patriarchy.”

“Even in your immediate spheres, your family, your friends, the various communities you belong to, in school, in college, in university, even in the workplace...if all of us who are aware do our part that will make a big dent,” she added.

Asked if the Philippines can be truly a gender-equal nation, Presto answered, “We are nearer than most but despite that, we are still far from achieving a gender-equal country.”