We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

Reina Mae Nasino did not know she was pregnant until February 2020, when she underwent a medical check-up before she was transferred from Camp Crame to the Manila City Jail. A member of the urban poor group Kadamay, she was arrested with two other activists on charges of illegal possession and firearms and explosives three months earlier, in November 2019 at the Bagong Alyansang Makabayan office in Manila.

The activists denied the charges, saying that the firearms had been planted in the office. Human rights group Karapatan called the police’s claim a “preposterous and a barefaced lie.” The National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL) also “vehemently and categorically” denied the accusations against the activists.

Being in a cramped jail cell in the Philippines, which has some of the most overpopulated detention facilities in the world, is already quite an ordeal. It is doubly so for an expecting mother. Throughout her pregnancy, Reina was seen by a doctor only a couple of times and received no other prenatal care aside from a daily folic acid supplement and one ultrasound, her lawyers said.

Her condition became grounds for her to seek release from jail amid the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside elderly and sickly detainees. But treating the inmates’ petition as an application for bail, the Supreme Court just tossed the case back to the lower courts.

On July 1, 2020, Reina gave birth to River at the Dr. Jose Fabella Memorial Hospital. Though born full-term, River weighed only 2.435 kilograms and had infant jaundice, so the hospital instructed Reina to breastfeed her baby “exclusively and on demand.”

Mother and child were returned to the Manila City Jail Female Dormitory the following day.

As her lawyers pleaded with a court to let Reina stay with her baby for 12 months, the first-time mom had trouble breastfeeding. She had to be coached by one of her attorneys, also a nursing mother, via a call because physical jail visits are prohibited amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

To counter arguments that Reina had to breastfeed, the jail warden claimed that Reina was actually feeding River infant formula. Kathy Panguban of the NUPL said this was a lie.

Panguban said her client resorted to mixed feeding because she thought her breast milk was not enough. “Reina had difficulty breastfeeding, but she did not stop,” the lawyer said in Filipino.

In her comment to a separate supplemental motion of the NUPL, Assistant City Prosecutor Rosalie Mazo-Atienza argued that the complainant’s requests could not be granted, considering that she was “charged with a crime which carries a grave penalty and her staying in a hospital would cost much on the government.” The prosecutor also claimed that providing a “nursery or a place for lactation inside the jail is not possible or highly improbable as it would require an enabling law or budget.”

Judge Marivic Balisi-Umali of the Manila Regional Trial Court did not allow Reina to stay with River. Citing information from the warden, the judge said the jail has no facility for newborn babies.

Umali has since recused herself from the case, and the criminal case against Nasino is now with another judge.

On August 13, 2020, six-week-old baby River was taken out of jail and into her relatives’ home. She would be hospitalized soon after. Though she tested negative for COVID-19, she was diagnosed with pneumonia, and her condition deteriorated.

On October 9, the pediatrician caring for her at the Philippine General Hospital reported that River’s lungs were deteriorating due to bacterial infection, and that she was no longer responding to medications. River “may expire any moment now,” Reina’s lawyers pleaded with Manila Regional Trial Court Executive Judge Virgilio Macaraig in an urgent motion asking him to allow Reina to be with her child.

Baby River died that night.

Reina is just one of hundreds of women in the Philippines who spent their pregnancies in jail in the past year. River’s death has triggered questions on how jail authorities treat mothers and pregnant women — and their babies — in their custody.

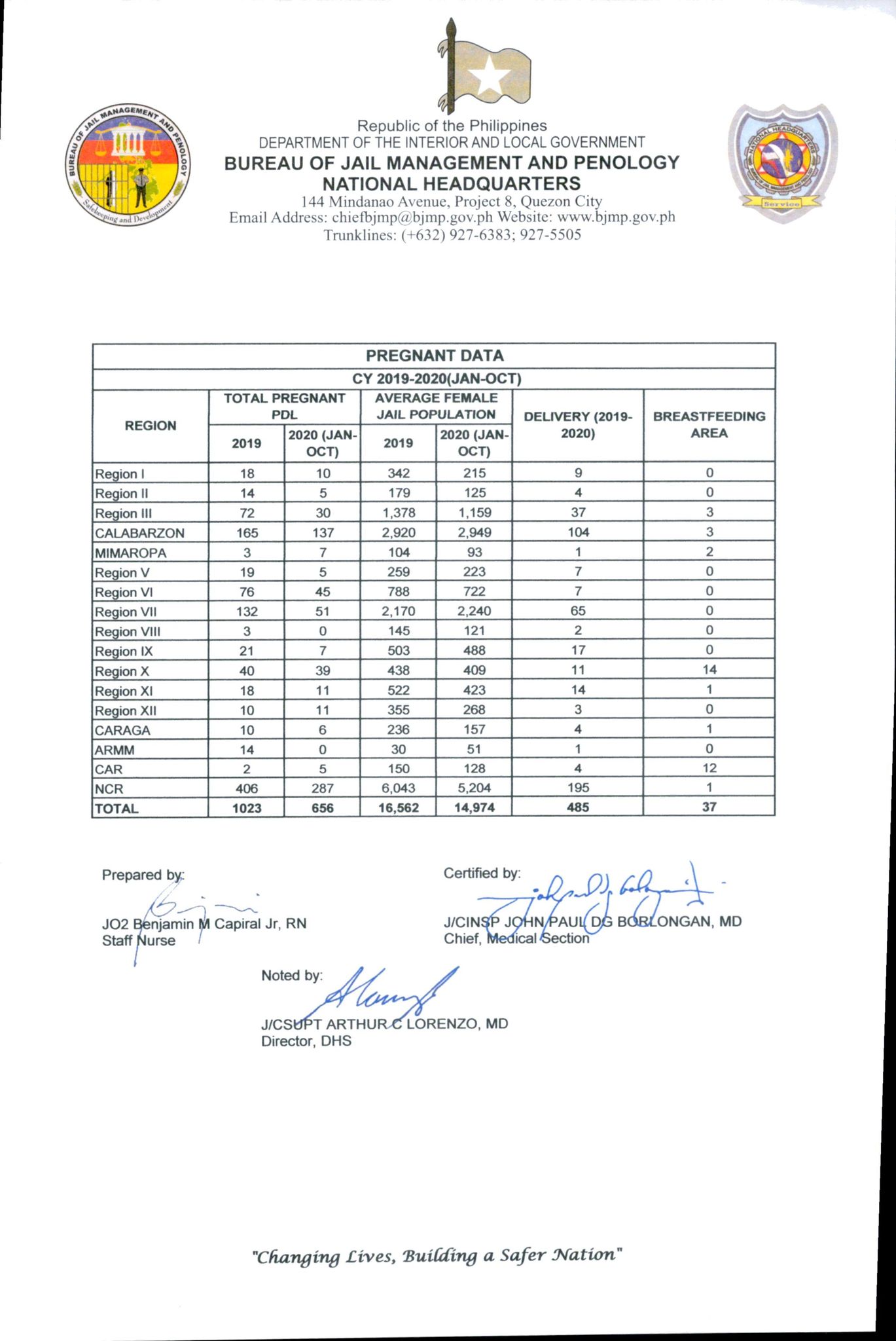

Pregnant women made up 4.3% of the female population at the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology’s (BJMP) facilities in the first 10 months of 2020. Of 14,974 female detainees, 656 were pregnant, according to bureau data. From 2019 to 2020, the BJMP recorded 485 childbirths.

The BJMP manages jail facilities that detain individuals undergoing or awaiting investigation, trial, or final judgment. Another government agency, the Bureau of Corrections, manages prison facilities for those who have been convicted.

BJMP policy states that pregnant inmates must receive check-ups from a jail physician or nurse, and only given tasks fit for their physical condition. When they are in labor, they should be brought to the nearest government hospital.

Breastfeeding is also protected by law. The Expanded Breastfeeding Promotion Act of 2009 also mandates all health and non-health facilities to set up lactation stations.

For its detainees, the BJMP says, there can be a “designated secluded space or area” that can be used as a lactation station when needed. There, nursing detainees can use the lactation station to express their milk three to four times a day “while accompanied by a female custodial personnel.” Nursing mothers must be given “ample privacy” during breastfeeding.

The bureau also allows infants to remain with their incarcerated mothers for up to one month, unless a doctor recommends they stay for longer considering the “best interests of the child within the scope of relevant domestic laws.”

The United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners, known as the Bangkok Rules, also state that prisoners “shall not be discouraged from breastfeeding their children, unless there are specific health reasons to do so.”

The BJMP says it is “putting [in] all efforts” for vulnerable detainees. But it admits it has its limitations.

Bureau spokesperson Xavier Solda said that while all jails have nurses, not all regions have a resident doctor. And according to BJMP data, there are only 37 breastfeeding areas scattered across 84 BJMP jails for women in the Philippines. “There is only one in Metro Manila, and none at all in many regions," he said.

In the absence of actual, designated places for pregnant and nursing women, it has been up to jail personnel to find spaces for the women they are tasked to guard.

“We can only do so much. Given the limited resources of the agency, we’ve always tried to provide for them, but we have a lack of space and a lack of funds,” Solda told GMA News Online in a mix of English and Filipino.

Reina and River spent 43 days together in total before they were separated. Though short, this is longer than the time Nancy (not her real name) had with her newborn daughter before she decided to entrust the baby to her family.

Nancy, a detainee in Central Visayas, gave birth to a healthy girl earlier this year. The next day, she turned the child over to her family, having breastfed her child only once.

In the months that have followed, she has heard nothing about her baby and her two other children. They live in an area where there is no cellphone signal.

Nancy said that she had many check-ups when she was pregnant and that the guards are kind, but the food was sometimes lacking.

She also said that she has no lawyer, and that she has not had a court hearing since her arrest last year. “It's tough because you could not be with your kids,” she said in Filipino.

Solda of the BJMP said most detainees opt to part with their babies a few days after birth, thinking they would rather be separated than let their child live in a jail. No child has stayed with their mother in jail for as long as a year.

But Dr. Jacqueline Kitong, a maternal and child health expert with the World Health Organization (WHO), disagrees with the BJMP policy allowing newborn babies only one month to stay with their detained mothers. “I think that’s not sensitive to postpartum women,” she told GMA News Online, saying that mothers should continuously and exclusively breastfeed their children for the first six months of life.

Without breastmilk, infants may become sickly, Kitong said. Being away from their mother would also deprive a child of the emotional bond they would otherwise have with skin-to-skin contact, she said.

The WHO officer said jail authorities must prioritize setting up maternal care facilities within detention centers.

If there are no actual breastfeeding rooms, jail officers could install a curtain in cells to separate the nursing mother and her child from the rest of the detainees, she said.

Kitong also said that jail nurses should counsel pregnant detainees on how to care for themselves and how to breastfeed; ensure they get proper nutrition, medical care, and exercise; and generally act as a support group.

In one case at the Taguig City Jail, a jail officer went above and beyond her job description to help a detainee out.

Officer Sallie Tinapay saw a detainee feeding her newborn baby infant formula last May, so she offered to help out. Also a nursing mother, the jail officer expressed her milk into a bottle and gave it to the baby. On the afternoon of the same day, she breastfed the baby herself.

“I feel happy about it... I didn’t think of the baby as a PDL’s child; I just wanted to breastfeed the baby because I felt sorry for it, and I love babies because I have a baby too,” Tinapay told GMA News Online in Filipino.

Some pregnant detainees have it better at the Davao City Jail. For more than a decade, female PDLs have lived in colorful “cottages” that resembled small homes rather than jail cells. Called the Ray of Hope Village, the facility was built by the civic group Gawad Kalinga in 2008. The detainees called themselves bakasyonistas.

Most of the detainees were transferred to a new dorm building last year, but senior citizens and other vulnerable PDLs are still in the cottages, jail warden Connie Sendrijas said.

Some of the cottages were converted into a worship area for Muslim detainees, an alternative learning classroom, a livelihood area, and a canteen. One serves as the infirmary, she said.

There are now 259 detainees in the facility. Two of them are pregnant, and two gave birth in September, said Sendrijas.

Sendrijas used to be the warden at the more traditional jail in General Santos City, and she said that though that was easier to manage in terms of security, the Ray of Hope Village offered a “home away from home” setup that helped the PDLs’ morale.

But for all this, resources are far from enough — this facility does not even have a resident doctor who could give pregnant women a regular health check. Sendrijas said personnel have to secure a court order to bring a detainee out to get a check-up in a hospital.

When a detainee gives birth, the protocol is to turn the baby over to relatives, she said. No child has been brought into the jail since she was assigned there a few months ago.

The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated matters, too: jail staff are locked in for 30 days at a time, scheduling hospital visits has become harder, and at times they did not know when a pregnant PDL was due because she had not seen a doctor before she was jailed, Sendrijas said.

Kitong, the WHO officer, said the pandemic may compel jail authorities to reevaluate their health facilities, especially for vulnerable detainees.

“For me, they should be more considerate and humane in the treatment of pregnant and postpartum and even the lactating mothers and their babies especially at this time of the COVID-19 pandemic,” she said.

“I think COVID-19 is teaching us these things. There will be pandemics that will be coming, or diseases that will be coming... it's high time that our jails should be ready for this.”

Disturbing Death, Delayed Grief

Peasant leader and peace consultant Ka Randy Echanis suffered a violent death that was meant to make him suffer. Even after his murder, the torture continued for his loved ones.

Tagged, You're Dead

Human rights activist Zara Alvarez swore how she feared for her life. Her violent death only served to prove her worst fear correct.

At the Correctional Institution for Women (CIW), where women are held after conviction, babies could generally stay with their mothers for up to six months. This could be extended to 12 monts if there are problems with who will take them in outside prison, Superintendent Virginia Mangawit said.

Five inmates gave birth this year, and no one is pregnant at this time,

The prison has at least eight nurses, and a doctor visits every week. The CIW also has a “mothers’ ward,” a 20-bed facility exclusive for pregnant women or inmates whose children are still in the prison. Three women and their babies are currently in the ward.

Babies could also be turned over to the detainees’ families just a few days after birth, Mangawit said.

In extreme cases where no one could care for the baby at all, the CIW coordinates with social welfare offices. In one instance, a prison nurse took in an inmate’s baby and is now in the process of adopting them, said Mangawit. Born at the height of the COVID-19 outbreak in the Philippines, the baby had nowhere to go.

At the Senate, a bill was filed on November 23 by opposition Senator Leila De Lima seeking to set up appropriate facilities in detention centers and prisons and introduce prison reforms in the treatment of women detainees, especially mothers and their children.

Senate Bill No. 1926 or the “Mothers Deprived of Liberty and their Children Act of 2020” stressed that human life, dignity and rights do not belong only to humans of the free world, but also even to mothers and their children inside detention facilities and prisons.

It proposed that all infants born to persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) shall remain with their mothers for the first twelve months after birth.

“Children who are born to mothers deprived of liberty while they await trial or while serving their sentence, are born without sin — they should not thus be made to bear the wrath and cruelty of this world,” De Lima said, citing River Nasino’s case.

Similar bills have been filed at the House of Representatives since 2013, but have failed to hurdle the chamber.

“Are we blaming the courts? Yes, we are. You could have done something, but you did not,” said Fides Lim of the prisoner rights group Kapatid, summarizing what many have said in outrage after the death of Baby River: the system has failed a newborn child.

The Integrated Bar of the Philippines spoke up as well. “Why can’t our justice system safeguard the needs and rights of an innocent child to breastfeeding and a better chance to survive?” asked IBP president Domingo Egon Cayosa.

For the young mother, the sorrow continued well after the death of her child. Reina Mae Nasino was initially allowed three days’ furlough to attend River’s wake and burial. But the officer in charge of the Manila City Jail’s female dormitory, Ignacia Monteron, pleaded with the court to shorten the furlough, saying there was not enough staff to monitor Reina for that length of time.

Ultimately, Reina was allowed to leave the jail for only a total of six hours: three hours for the wake, and three hours for the burial. Her heavily guarded visit at River’s wake, however, was cut short due to commotion and “tension” at the scene, with a Kapatid representative accusing her escorts of pulling her away while she was being interviewed by reporters.

On October 16, Reina was brought to the Manila North Cemetery to attend River’s funeral.

Handcuffed and once more under heavy guard, she was unable to embrace her baby’s casket, but was allowed to approach it to say goodbye.

In their final reunion, Reina, surrounded by a throng of police officers, clutched a flower as she tearfully stared at her baby in her tiny coffin, barred by handcuffs from even touching River for the last time.

Three hours later, she was returned to jail.

Reina’s lawyers have asked the Supreme Court to dismiss Umali, the judge who turned down Reina’s request for River to stay with her in jail.

“When [Judge Umali] ignored the existence and applicability of RA 10028 (Expanded Breastfeeding Promotion Act of 2009) to this case, she essentially ruled that nursing detainees and their children like the complainant and baby River have lost the right to adequate food and the right to highest attainable standard of health at the prison door,” the NUPL said in its administrative complaint.

The lawyers said Umali’s orders led “to the forcible weaning of her newborn child, which led to her serious illness and eventual demise.”

“Baby River’s death is on her doorstep,” they said.

On December 2, another activist Amanda Lacaba Echanis was arrested, also on the charges of alleged illegal possession of firearms, in Baggao, Cagayan. According to reports, about a hundred policemen swooped down at dawn at the house where Amanda was staying and went over the area and later on purportedly found an old M16 assault rifle, two hand grenades and assorted ammunition. The search warrant would appear after the search was conducted, her lawyers claim.

A month before the arrest, Amanda had given birth to baby Randall Emmanuel. She was shocked at the police’s firearms loot, insisting she only had relief goods at her home, which just got flooded due to the typhoon.

“Wala po akong baby armalite, baby lang. Wala po akong pampasabog, pasabog na balita lang: surprise, it’s a boy! [I don’t have a baby armalite, just a baby. I don’t have any explosives, just explosive news: surprise, it’s a boy!]” she said in a video message released by the rights group Kapatid.

Taken by police, Amanda insisted on bringing her baby so she could also continue breastfeeding. In detention, she said her baby has a good appetite but wished she was not rearing him inside the jail.

“Makakaasa kayo na tuloy lang ang laban, at sana makalaya na kami dahil alam naman natin na gawa-gawa lang ang akusasyon [Rest assured that the fight will continue, and we hope to be free again because we know that the accusations are made up],” she said.

Amanda, 32, is the daughter of peasant leader and peace consultant Randall Echanis, who in August was brutally killed in his apartment in Quezon City.

When she was two years old, Amada was also detained along with her parents at Camp Crame.

“Tiny, with doleful eyes, which seemed too big and old for her, baby Amanda maybe saw more than we did. I remember we would all laugh whenever she blurted out the individual owners of all the water pails and water jugs (for drinking water) lined up every morning in front of the gripo [faucet] in the open area outside the common kitchen. She could also identify all the clothes hanging up to dry per owner,” Kapatid’s Lim wrote in Facebook post.

Randall and wife, Linda, had their own kubol, or booth, in jail, “strung up with cloth to provide some privacy while Linda breastfed Amanda and put her to sleep.” Linda was released after six months and took care of Amanda as she worked for the freedom of her husband.

Amanda would pass the highly competitive exam for the Philippine High School for the Arts and then the University of the Philippines. She would become a playwright, a painter and poet.

“But on December 2, the youngest political prisoner in our time became a political prisoner herself,” Lim said.

Several groups have started initiatives for the release of Amanda and her baby.

“Unfortunately, this is not an isolated case but rather one of many. What has happened to Amanda is a form of silencing known as 'red-tagging,' in which individuals and organizations are accused of being communists and terrorists,” the Southeast Asian Feminist Action Movement said in a statement.

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) noted that Amanda’s arrest "is the latest in a string of arrests and attacks against alleged members of the New People’s Army.” In a congressional hearing, CHR Commissioner Karen Dumpit added that red-tagging "continues to threaten life, liberty and security of human rights defenders across sectors.”

“It cannot be denied that tagging is a matter of serious concern that should not be taken lightly. Aside from the delegitimization of dissent and public stigmatization, it is more often than not a prelude or even an open invitation for anyone to commit atrocities against the persons tagged,” she said.

Maria Sol Taule of the National Union of Peoples' Lawyers said Amanda's arrest in the wee hours of December 2 followed the same "pattern” as the arrests of other people whom police and military accuse of links to the communist rebel movement.

“We don't want another Baby River, wala pang ilang buwan ang nakakalipas, ganito na naman yung storya [it has not been a few months and it’s the same story all over again],” Taule said.

Family and friends of Amanda Lacaba Echanis hope the court will exercise compassion in dealing with her case, even as they stood firm that the charges against her were false.

Poet, playwright and press-freedom fighter Pete Lacaba, Amanda’s uncle, said: “Dapat manaig ang humanitarian reason para mapalaya si Amanda at si Baby Randall Emmanuel sa lalong madaling panahon. [Humanitarian reason must prevail so that Amanda and Baby Randall Emmanuel may be freed as soon as possible].”

Her mother Linda could not hold back tears as she appealed for Amanda’s release.

“Sa mga kinauukulan, kayo rin ay may pamilya, may mga anak at apo at kung may natitira pang pagkatao sa inyo, sana'y maintindihan din ninyo na hindi dapat hinuli at kinulong ang aking anak na si Amanda [To those concerned, you have families too, children and grandchildren, and if there is any humanity left in you, I hope you can understand that my daughter Amanda should not have been arrested and jailed]," Linda said.

UNICEF’s office in Manila said that in any decision affecting children, the primary consideration should be the best interest of the child.

It said the government needs to promote breastfeeding given “strong scientific evidence” that it can, alongside the proper introduction of complementary feeding, help prevent newborn deaths and common childhood infections like pneumonia and diarrhea.

“The Philippine government has all the laws and policies that are aligned with international agreements, the challenge is the enabling environment for the policies to be implemented,” UNICEF told GMA News Online.

“As these children are not prisoners, they should not be treated as such,” it said.

On the day baby River died, the NUPL mourned the system that allowed her to sicken and die without her mother by her side. It warned that unless things change, such cruel tragedy is bound to happen again.

“We have not only lost our hearts, we have lost our souls if we do not feel the pain and the rage,” the group said. “We will lose our humanity if we see more Baby Rivers again.”

Editing by Norman Bordadora, Lira Dalangin-Fernandez, and Barbara Marchadesch.