We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

“Cuts,” if coming from the government censors, is that four-letter word that filmmakers dread.

Veteran director Mike De Leon isn’t an exception and he may have a tip or two to younger directors based on his experience with “Kisapmata” and the censors exactly 39 years ago.

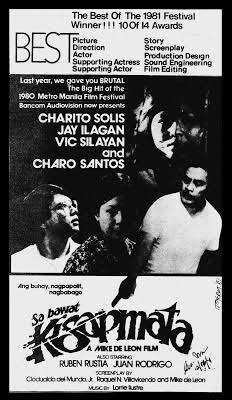

One fateful day in early December in 1981, De Leon was summoned by government censors headed by former senator and beauty queen Maria Kalaw Katigbak. “Kisapmata” was finished and already accepted in that year’s Metro Manila Film Festival, just waiting for the approval of the Movies and Television Review and Classification Board.

At the time, the word digital may have been limited to wrist watches and calculators, while movies were shot using rolls of film negatives. If you say cut, editors literally used film splicers and sometimes scissors.

“In trying to get ‘Kisapmata’ shown at theaters, I had my most awful experience with the censors, especially in the person of the Madame Chief Inquisitor herself, Maria Kalaw-Katigbak,” De Leon wrote in his unfinished book tentatively titled “Last Look Back,” a chapter of which this writer was given access.

De Leon continued: “I will never forget her first words to me when we met at her residence. She said, ‘I was just on the phone with the President (Ferdinand Marcos), and he said, ‘My God, incest! What kind of films are you showing in the festival?’

“Whether she was making it up or not, I will never know, but she succeeded in instilling instant fear and loathing in me. I was in the presence of a Wagnerian Valkyrie who brooked no dissent,” De Leon added.

“Then she began her spiel. She insisted that my shot of the lower half of Tatang Dadong’s body, as he was coming into his daughter’s room one night, showed him in an obviously aroused state. I was flabbergasted by this preposterous remark; this woman’s imagination was more vivid than mine.”

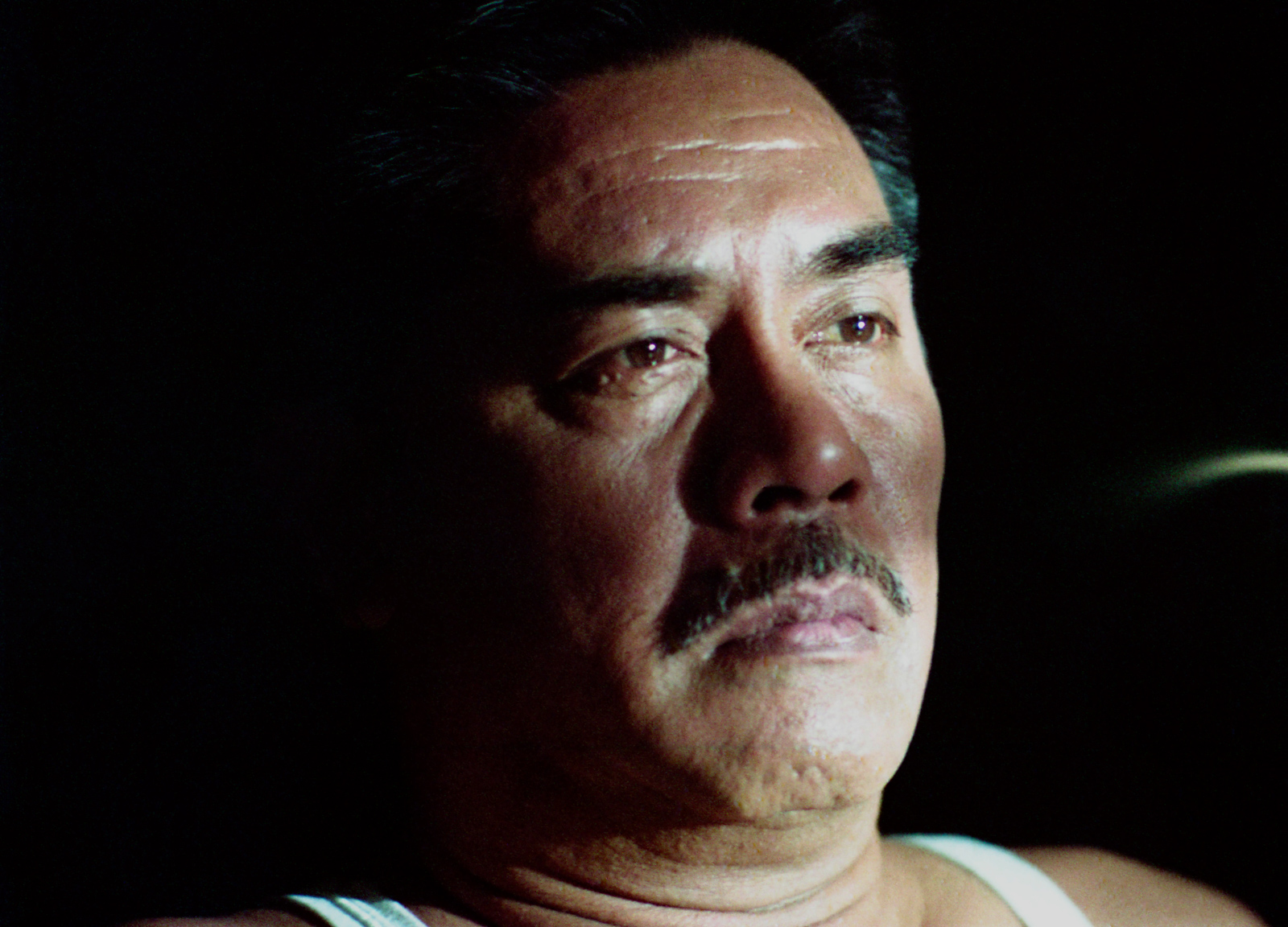

Tatang Dadong is the retired policeman played by Vic Silayan and the daughter was played by Charo Santos. Already an established actress, having starred as lead in other films like in De Leon’s 1976 classic, “Itim,” Santos also functioned as “Kisapmata’s” line producer.

Silayan acknowledged this “aroused state” three years later after making “Kisapmata,” in an interview with documentarist, former De La Salle professor Manny Reyes. Titled “Vic Silayan: An Actor Remembers,” incidentally the biographical documentary has since been made available on Vimeo, through Casa Grande Vintage Cinema Facebook Page and on You Tube.

Going back, De Leon continued: “Jess Navarro, the film’s editor, and I were made to examine the shot frame by frame, and although we knew she was spewing nonsense, we had to do what she wanted. She was adamant that it was there. The shot, she said, had to be cut out from not only all the prints but from the original camera negative as well.

“After that traumatic encounter, we went back to LVN, which was then having its Christmas party. We interrupted the merry-making of a couple of lab technicians, hurriedly made a duplicate negative of the shot, and spliced it into the master negative of the film.

“The following morning, wearing appropriately grim faces, we performed the cut in Mrs. Katigbak’s presence and handed over the excised duplicate negative to her. Although I was elated that we were able to outwit this arrogant and supposedly highly educated woman de buena familia, I also felt deep anger and depression.

“No film director should ever have to experience such a horrible ordeal. This humiliating experience was worse than my overnight detention at that military camp in 1972.”

De Leon wanted to make the film as early as 1978 but there were no producers willing to gamble on a subject as dark as “Kisapmata.” It was Bancom Audiovision, a subsidiary of Union Bank, that took it in the early 80s, the same producer behind “Jaguar,” “Brutal” and “Aguila.”

As cineastes and cinephiles would know, “Kisapmata” was an adaptation of Nick Joaquin’s reportage titled “The House On Zapote Street.” Writing as Quijano de Manila, it was first published on the country’s number one news weekly, the Philippines Free Press magazine in January 1961. It became part of Joaquin’s collection “Reportage on Crime,” first published in 1977.

De Leon co-wrote the script with Clodualdo “Doy” del Mundo and Raquel Villavicencio.

In an earlier interview, De Leon said among the films he did with production designer Cesar Hernando, “Kisapmata” was Hernando’s best work. Cinematography was done by Rody Lacap, Music by Lorrie Ilustre and Sound by Ramon Reyes.

Looking back, De Leon said “Kisapmata” was finished quickly, in about three months, because they had no big stars.

“We had no egos to massage, no new actors to promote. All we had to do was concentrate on making a good film with the finest actors we could get.”

Charito Solis and Charo Santos perform in a scene in "Kisapmata." Director Mike De Leon said filming finished quickly because "there were no egos to massage." Image courtesy of Mike De Leon.

“Although we were shooting continuously I knew that the script, having undergone several drafts, was not giving me the ending I was looking for. Finally, I re-read the newspaper account as well as Nick’s account. And I realized there could no longer be any drama at the end. Everything had to happen fast—in the blink of an eye (Sa Isang Kisapmata),” De Leon recalled.

“I had a rather lengthy discussion with Nick after he finally got to watch the film and was paid for his article. He told me that he thought I had access to the actual police reports because there were several scenes in the film that showed details that were never released to the public.

“One of them was the daughter’s bed. Since I kept showing the bed, he thought that I was leading to the climax of the true account. In the police reconstruction of the father’s suicide, it seemed that after shooting his family, he lay down on his daughter’s bed, rested his head on her pillow, and then shot himself.

“I told Nick that I didn’t know this at all. My purpose in showing the bed was to visually remind the audience that there were sexual relations between father and daughter. Nick told me more disturbing details about the story that could have been included in the film had I been allowed to speak to him before the production. One very disturbing detail was that — unbeknownst to the young couple — the father hid under their bed as they slept.”

The tragic incident was obviously headline news. From a Manila Chronicle frontpage story, the actual shooting took place late afternoon on January 18, 1961.

Shot to death were newly-wed couple, medical doctors Leonardo Quitangon, 36, and Lydia Cabading-Quitangon, 24. The report described it “amok” by 45-year-old police detective Pablo Cabading, who blew his brains out.

The wife who survived was 45-year-old Asuncion.

De Leon discovered Cabading was even worse than how Joaquin portrayed him in his reportage. While doing his own research, he found out Cabading had two wives.

"We also checked the obits at the National Library and aside from the newspaper with the screaming headlines, the cop Cabading had two obits because he had two wives! But I didn't include that in my film," said De Leon.

In the film, Quitangon is Noel Manalansan (played by Jay Ilagan). He works in a bank with his wife Mila, played by Santos. In the film, Ruben Rustia plays the father of Noel Manalansan.

Cabading is Tatang Dadong, a retired policeman played by the magnificent Vic Silayan.

Among cineastes, Tatang Dadong, for which Silayan won Best Actor, is his signature role.

In his biographical documentary, Silayan recalled how he “attacked” the role.

“With ‘Kisapmata,’ it was not simply authoritarian but it was insane possession. We made him appear with moments of lucidity and moments of derangement,” Silayan told Manny Reyes, the documentarist.

“I felt that I could keep people scared that way because when he was normal, they would know when suddenly he would erupt like a volcano. I would precede his outburst with slight motion to his forehead to indicate that a headache would start and that he would lose, go to temporary insanity. Pretty soon, that was the signal, he would scare people.”

Tatang Dadong remains among the scariest, hideous characters in the history of Philippine cinema.

Asuncion is named Dely, the submissive wife played by Charito Solis. Based on the Manila Chronicle story, Asuncion reportedly sustained eight wounds — “five in both feet, two in the left shoulder and one in the body.”

De Leon recalled: “In the original account of what happened in 1961, the wife, though shot several times, survived, but we changed this detail in our adaptation — in the film, everyone dies.”

Asuncion did not only survive the fatal shooting. In her mid-60s, she was still alive in 1981, or about two decades after the horrific incident. She filed charges together with the surviving heirs of Leonardo Quitangon against the producers.

De Leon recalled: “The adaptation was reset in the present time (1981), and we completely forgot about the fact that the wife did survive. I still remember the creepy feeling I got when I saw the TRO at the booking office of the production company: the wife herself had signed it.”

“Although her signature seemed written by a shaky hand, it was sure evidence that she was very much alive. But in my fertile mind, it felt like she had come back from the grave to accuse us. I don’t know how the impasse was resolved, but perhaps because Nick's article was a published document in the Philippines Free Press. Anyway, the TRO was lifted and the film opened on schedule on December 25th,” he added.

But all’s well that ends well.

As we all know, “Kisapmata” won 10 awards in the MMFF, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Actor. The following year, together with De Leon’s “Batch ‘81,” the film was shown at the Directors’ Fortnight in the Cannes Film Festival.

“What I can recall is that the head and co-founder of the Director's Fortnight, Pierre Henri-Deleau and his assistant Jacques Poitrat came to Manila in January 1982 and they wanted to see my films. Especially ‘Kisapmata’ and ‘Batch 81,’ which was still in the post-production stage,” De Leon said in an email to this writer.

“They got to watch ‘Kisapmata’ but it was still the theatrical version which I later re-edited and re-mixed for Cannes,” De Leon continued.

“Then Pierre-Henri asked to see ‘Batch 81’ and all I could show him at that point was the edited (black and white) rushes. Knowing how tight-lipped the French were about committing, I did not expect anything.”

A few weeks later, De Leon got a call from Marichu Maceda, the producer of “Batch ‘81” asking him for a meeting in her residence.

“Pierre-Henri and Jacques were there, as well as Charo and (co-producer) Simon Ongpin for ‘Kisapmata’. They informed me that they were taking both films for the Fortnight. Of course, I was very happy since it was an unusual and unique offer, two films by one director, they kept on saying.”

“Kisapmata” is regarded by critics and cinephiles as De Leon’s best and among the masterpieces of world cinema.

New York-based media producer and writer Gil Quito wrote: “It’s a reflection of Mike's influence on the current generation that in the latest poll conducted among filmmakers, critics and academics by ‘Pinoy Rebyu’ on the 100 greatest Philippine films of all time, Mike is the most represented of all directors, alongside Lino Brocka, in the top dozen films, which includes ‘Kisapmata.’”

“Of the classics from Philippine cinema's Second Golden Age, I think that ‘Kisapmata’ is the work that has dated the least, with its continuing psychological and social relevance and timelessly spare and lucid mise en scene. According to Davide Pozzi, the Director of L'Immagine Ritrovata, the ‘Kisapmata’ restoration is one of the hardest he's ever worked on (due to deteriorated elements) but he really believed in the film and went to extraordinary lengths on the work,” Quito added.

Lawyer-critic Oggs Cruz, as early as 2006, wrote in his blog that among De Leon’s films, “Kisapmata” is his masterpiece.

“(Alfred) Hitchcock is an obvious influence,” Cruz wrote. “Yet the creepy thing about ‘Kisapmata’ is that the events are all too real, unlike Hitchcock's ‘Psycho’ wherein the murderer is merely haunted by a domineering yet dead mother.”

In his review for Business World on March 27, Noel Vera wrote: “Easily Mike de Leon’s masterpiece and in my book one of the greatest of Filipino films.”

Cinephile Maribel Legarda saw the film when she was still a colegiala in Assumption University in 1981.

Now the artistic director of Philippine Educational Theater Association, she recalled: “I loved it... how he created that scary oppressive mood in that house and the performers were also so good.”

Now, what these critics, cinephiles, cineastes and fans of De Leon’s films have seen was the MMFF copy or the theatrical version that has made the rounds of local festivals and video-on-demand streaming services like iWant and the-now shut down Hooq.

In an earlier interview, De Leon said when he supervised the MMFF version, there were one or two additional scenes that were removed when he re-edited and remixed the film for foreign screenings.

“Many sound effects were present in the MMFF version because I thought the film was too quiet and even more noncommercial. I cleaned it up when I made the definitive mix after the MMFF,” De Leon said.

As the story goes, Bancom Audiovision, the production company behind the film went bankrupt and was shut down in the early 1980s. BA was a subsidiary of Union Bank.

The original negatives of the film’s final cut, or the one sent to Cannes, ended up at the U.P. Film Center Archive.

“I tried for so many years to secure permission to access the materials and make a print for archival purposes. I wrote the bank several letters but all responses were coursed through their legal arm who expressed no interest in what must have seemed to them an inconsequential matter. In the meanwhile, the film elements not only of ‘Kisapmata’ but all the other films produced by that company started to deteriorate,” De Leon said.

De Leon took an early retirement from doing films after 1999’s “Bayaning Third World.” It was only after 18 years he re-emerged when he did “Citizen Jake.”

In those decades, there was an opportunity to retrieve the already deteriorating film negatives when De Leon was offered by a local film festival to have a retrospective of his works.

“My initial reaction was to say no but Cesar (Hernando) convinced me to agree,” said De Leon.

Hernando reasoned out it’s the perfect opportunity for the negatives to be turned over to the lab and a print made before it’s too late.

“Fortunately, the negatives were turned over to me,” De Leon recalled.

Imagine the prodigal son, knocking on the door after decades of wandering, wearing beggar’s tattered clothing, his body afflicted with wounds and scabies, almost on the brink of death.

“When I first saw the film cans, my heart sank. They were all covered in rust and had a rancid smell—telltale signs of the vinegar syndrome.”

To make a long story short, the film negatives needed major surgery.

“The LVN archive guys started the delicate task of cleaning the film immediately. As it turned out, the rust had not yet affected the film negatives but magenta-colored mold—fungal growth—had spread all over the film. But the archive did not possess the knowhow to remove or even arrest the spread of the mold,” De Leon said.

“Historian Ambeth Ocampo entered the picture as chair of the National Commission of Culture and the Arts. He said he received a request for a grant to restore ‘Kisapmata’ and asked if I knew anything about it. I said no. This was not digital restoration yet, but film restoration. I told him that I did not own the rights to the film but legally I owned the print in Singapore because I spent for that.

“Some months passed and Ambeth sent me the ‘restored’ film — in an official NCCA brown envelope. The restored film in an envelope? I opened it and aside from Ambeth’s letter, there was a lonely looking DVD inside. I watched it and saw that it was a mere copy of a low-resolution version of the film, probably from a 3/4 inch U-matic tape.”

It turned out, what Ocampo had was the MMFF version, not the final cut version sent to Cannes. More days and months passed, the search for these film negatives continued.

When Briccio Santos took over the Film Development Council of the Philippines or FDCP, as mandated by law, he started the FDCP film archive. All films from government media offices were sent to the FDCP archive, one of them being the U.P. Film Center archive.

“But when his staff went there to pick up the films, there was one single title that was not there and yes, you guessed it. It was ‘Kisapmata.’ It had gone missing again. I asked Briccio to help me retrieve the film from wherever it was being kept — illegally,” De Leon recalled.

“Finally, the film elements were ‘found’ but all the sound negatives were missing and only two out of the original five reels of camera negatives were still usable, if at all. The rest had turned to mush.”

After the completion of “Citizen Jake,” De Leon found out that the present legal copyright holder of the film was Solar Films, which happened to be the distributor of “Citizen Jake.”

“I offered to buy the rights from them. They only owned a tape of the film while I had an original print in Singapore. They denied my request. I said that ABS-CBN was willing to buy the rights, too, and would restore it. They refused that, too. So I asked them to restore it themselves. They said they were not into restoration. It was bizarre that they wanted to hold on to the rights but did not seem to be interested in bringing the film back into circulation,” De Leon said.

“By this time, after many years since my first collaboration with L’Immagine Ritrovata in the restoration of ‘Maynila Sa Kuko ng Liwanag’, their lab had already developed sophisticated techniques in digitally removing the green mold on the film and Davide Pozzi, the head of the lab who had become a good friend was aware of the unfortunate history of this film.

“He and his team painstakingly restored the film and told me that it was the most difficult restoration work they had ever encountered. I congratulate them for a work well done. I also wish to congratulate Roque Magsino, the colorist at Wildsound for further important corrections during the grading of the film.”

De Leon added it was only early this year when the real owners of the film surfaced, Union Bank. It turned out Union Bank has begun searching for the missing films of Bancom Audiovision, almost three decades after it was shut down.

At this point, the restoration of ‘Kisapmata’ in Bologna was in place, using film materials that De Leon kept at the Asian Film Archive in Singapore.

When Union Bank learned about this, they offered De Leon a co-ownership and reimbursed half of the restoration costs.

De Leon, in hindsight, said the lesson of the “Kisapmata” saga is this: “Filmmakers should not only preserve but own their work or at least have a say about its legacy. Film should be a balance of art and commerce but the issue of intellectual property should be a concern for all film artists deserving of the name. But one thing is clear about this film and can no longer be changed. ‘Kisapmata’ is back. Restored.”

The 2020 restored version also gave proper credit to Joaquin, whose name was omitted in the earlier versions.

“Nick was not given due credit in the (1981) film, because the producers wanted to avoid any explicit reference to the writer’s factual account of the case. I argued against this decision because it would be quite difficult for a viewer to suspend one’s disbelief if the film was presented as fiction,” De Leon recalled.

The restoration was done at L'Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, Italy and Wildsound Studios in Manila. It had a live theatrical screening on August 31 this year in Bologna, Italy, as part of the 34th Il Cinema Ritrovato, a festival of recovered and restored classics.

For the record, it is the first Filipino film to be shown in an actual theater during the pandemic to a live audience since the Philippines was put on a lockdown starting March 15.

And now for the first time, “Kisapmata” the 2020 restored version (with English subtitles) will be made available for free on December 19, Saturday, from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m.. The link will be posted on the Facebook page of Casa Grande Vintage Cinema.

People who have the tendency to overthink might wonder: What makes December 19 special? If we google it, the date would fall on the 24th death anniversary of Marcello Mastroianni and, well, the Bill Clinton impeachment.

De Leon’s original idea was to stream “Kisapmata” on December 20, the same date in the film when the tragic shooting incident took place. For some strange coincidence, like in the film, the date falls on a Sunday.

“But there would be more viewers on a Saturday, the 19th,” De Leon simply reasoned out.

More than anything else, “Kisapmata” is obviously about strongman rule, an allegory on the Marcos Dictatorship. If Tatang Dadong sounds like someone famous and infamous now, it is pure coincidence, or something prophetic.

De Leon said, “I am calling it the most macabre Christmas movie ever.”