We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

By ANTHONY Q. ESGUERRA

May 28, 2020

The telephones are ringing off the hook. The once silent office, occupied by one or two people since the lockdown was imposed in Metro Manila, immediately turns into a war room.

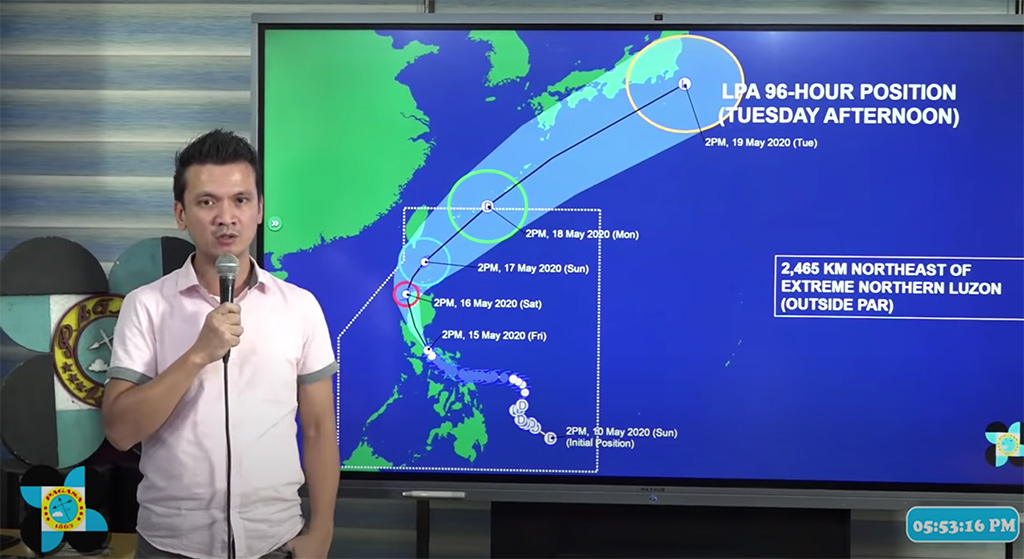

As the Philippines scrambled to defeat the deadly COVID-19, trouble brewed in the seas hundreds of kilometers off Mindanao. The low-pressure area (LPA) threatens the country still reeling from the disruptive impact of the pandemic.

On Sunday, May 10, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) sends out its first warning that the LPA would become a tropical depression and would likely hit land.

Chris Perez had to be in the office. The strict social distancing measures to slow the spread of the coronavirus has allowed him to work from home and be with his family for almost two months.

The strict quarantine measures in Luzon affected the livelihoods of some 58 million Filipinos and shuttered businesses and institutions. Many government offices remained closed, too.

But not PAGASA.

For two months, state forecasters monitored and predicted weather from the comforts of their homes.

It is a highly specialized job. The government has only 17 national weather forecasters in Metro Manila. With the lockdown, one or two of them would come to the office to run the service, while the rest worked from home.

The weather bureau has 58 synoptic stations, 23 agromet stations and 16 radar stations, manned by some 800 PAGASA personnel, scattered across the country. These are manned by PAGASA personnel, pandemic or no pandemic.

“We cannot leave the office,” Chris says. “There are calls from the media: broadsheet, TV, radio and social media. We need someone to be there to take the calls.”

But as “Ambo” (international name: Vongfong) slowly inched toward the country, working from home would not quite be enough.

As the supervisor of the weather forecasting section, Chris needs to make sure that there were enough warm bodies in the office to track the skies and map the looming disaster. He is immediately shuttled from Bulacan to PAGASA headquarters in Quezon City.

In his nearly 17 years in the weather forecasting service, Chris has weathered many storms. But he knew that Ambo was different.

“It’s the first time we’re having a storm in the middle of a pandemic,” Chris tells GMA News in Filipino. “Some of my colleagues thought, ‘Not now please, not now.’”

But no one has power over the weather.

Ambo was the first typhoon to form in the Western North Pacific during a pandemic that altered the way billions of people live around the world, including the Philippines.

The standard operating procedure is to require forecasters to report back to the office once a threat of typhoon arises. One by one, weather forecasters arrives in the office. It’s now all hands on and deck and work from home was cancelled for now.

“It’s like a reunion of some sort,” he says. “We’re meeting again after working from home in almost two months.”

Ariel Rojas has to cancel his day off. He lives near the PAGASA headquarters, but he has to pack clothes, food and essential stuff. The junior forecaster knows he would not be leaving the office until Ambo exits the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR).

“When the storm was brewing, we were asked to come in,” Ariel says. “I just live near the office so I signed in.”

The forecasters have to live temporarily in their office in Quezon City to minimize their exposure and interaction from people. They thought of this safeguard to protect everyone from the virus. Outside PAGASA are several of the government’s biggest hospitals that cater to COVID-19 patients. There is a risk of interacting with a person exposed to the virus.

“The bosses always reminded us to practice social distancing and of course to face masks,” Ariel says. “A lot of people coming in together from different places. Even we were isolated before, you know, somewhere, as we came in the office or when we were fetched from our homes, someone could have interacted with someone infected with the virus.”

For a week, their office would become their temporary home. They sleep in an unused lounge and rooms converted into a sleeping quarter, furnished with several beds good for 10 people. Men and women stay in separate rooms. They hve no choice but to take their baths in the office restrooms.

“We do prepare our food in the office pantry. Someone cooks the food – breakfast, lunch and dinner – someone is also assigned to do the dishes. We have a schedule for that. Someone was in charge of doing the grocery, too,” Ariel says, a little chuckle escaping him.

The household chores give them a different kind of exercise in collaboration. It is also a bonding of sorts for them.

“This is just first the storm, so we are still okay,” he says. “Our office is like a newsroom when there’s a storm. Everybody does their own thing, someone has to look at the map, someone has to analyze the weather data. The phones are ringing non-stop. Everyone is talking, sometimes there’s a shouting match.”

More people are needed to track the storm, to get the message to the public and key government institutions as fast as possible.

The forecasting section has five telephone lines. All five ring at the same time. They receive 50 phone calls a day, per their conservative estimate. Most of the calls take place in the morning when more people tune in to the radio for the latest on the weather. Another large wave of calls hit them in the evening for the primetime newscasts.

“It takes a toll on our voices. After a while, you will lose it,” Ariel says.

There are two to three typhoon forecasters who closely monitor Ambo round the clock. From eight hours, their shifts are extended to 12 hours.

They prepare the weather bulletins, a comprehensive brief of the storm’s path, the time when it will hit land, its strength and the weather signals for affected places.

At least three more forecasters answer the phone calls, taking questions from broadcasters and journalists who relay the information to their larger audience

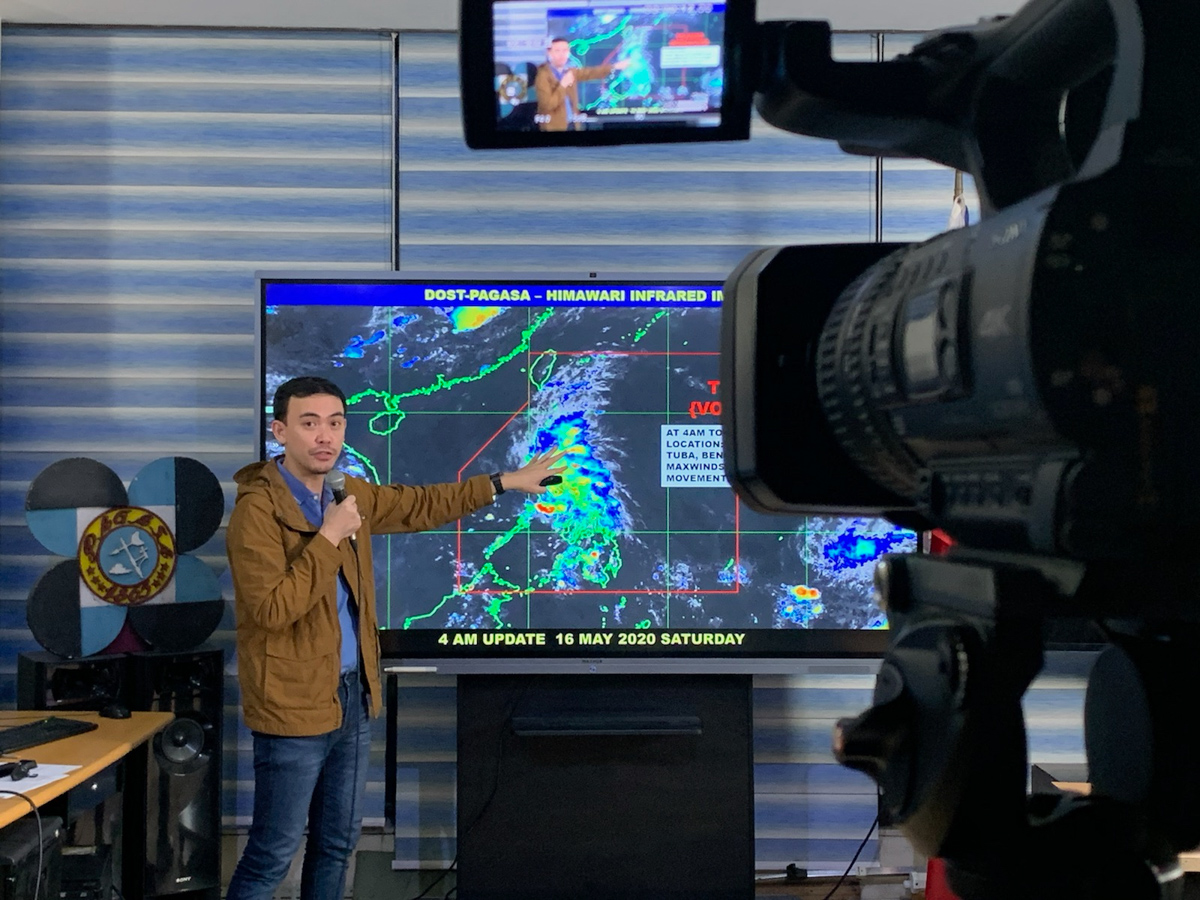

The modern PAGASA is capable of broadcasting weather updates through social media platforms like Facebook Live and YouTube, allowing them to connect more directly to people. The PAGASA Facebook page has close to four million followers. The briefing on Ambo garners hundreds of thousands of views. The forecasters also take turns doing the live broadcast.

In times like this, working at the office becomes essential because communication is a challenge when they were working remotely.

“Forecasting is actually a consensus,” Ariel says. “You need to analyze all the data available to you – satellite data, weather data from all synoptics stations of PAGASA, and other technical stuff. You discuss these things with your co-forecasters. You need to come up with a consensus.”

He adds that typhoon forecasting requires more people and more frequent checks on all systems.

Ambo intensifies into a Severe Tropical Storm on May 13. A day later, it makes landfall in Eastern Samar, the first of seven it would make as it battered the country.

To determine a typhoon’s landfall and path, “every three hours, you need to analyze the data, someone has to type the bulletin and do the other components, so the typhoon forecasters can focus on their forecast,” Ariel explains.

PAGASA weather forecasters are the silent frontliners of pandemic Philippines, but their voice needs to be the loudest at a time of a storm just like Ambo.

“With our without a storm, we are frontliners,” Chris says. “Even if there’s a holiday, we are in the office. The weather knows no holiday. We can be considered frontliners, with or without a pandemic.”

When the COVID-19 crisis began, his wife worried for his safety as he continued to go to work.

“If you are a forecaster, you have a certain level of courage. I think forecasters are naturally brave. May pagkabayani, may pagka-martyr. We weather many storms,” Chris says, befor admitting the coronavirus carries a different level of risk.

“But this time it’s different because we’re fighting something we don’t see and feel.”

Each time they go out, there is a risk of contracting the virus and passign it on to their loved ones when they return home. “It’s a huge risk.”

But while the country honors the heroism of frontliners in healthcare, security and essential commercial establishments, sometimes the people of science are forgotten.

Chris shares an incident when some medical and security frontliners were given priority at a queue. He wishes they would also be recognized or at least given some sort of courtesy.

Unlike healthcare workers who are recognized because of their uniforms, there is no way to identify the weather forecaster from everyone else.

“Yes, I am an essential government worker, but they don’t know that,” he says.

Still, he is elated when TV anchors acknowledge that PAGASA forecasters are frontliners on live television when he delivers the weather report.

An electronics and communication engineer, Chris joined PAGASA’s weather instrument division in 2000. He became a weather forecaster in 2003 after taking up an opportunity to study meteorology and forecasting. He even went to Australia to further his studies.

Chris identifies as his inspiration and role model Nathaniel “Mang Tani” Cruz, the GMA Resident Meteorologist who served PAGASA almost 30 years as the official spokesperson of the weather bureau.

As a longtime PAGASA figure, Mang Tani understands the importance of the work of his former colleagues.

“We still need weather information and getting this has become even more challenging because of the pandemic,” Mang Tani says.

People need the services of PAGASA now more than ever, he says, even if they don’t realize it.

“The pandemic is not yet over, the crisis is still here and here comes the rainy season,” he says. “We badly need the services of our weather guys.”

Filipinos should also show appreciation for weather forecasters, the field personnel and observers who track the Philippine skies.

“They’re frontliners, too. They don’t directly save lives like other frontliners, but providing weather information is one way of serving,” Mang Tani says.

The role of PAGASA for the country is clear for the 33-year-old Ariel.

“We are in the business of saving lives,” he said, “The only difference is that our healthcare workers are more personal, face to face. We in PAGASA attend to 110 million people.”

Ariel's journey to becoming a meteorologist was unconventional. He finished food technology before taking a master’s degree in meteorology. He was quizzed during his scholarship interview for his master’s degree: Why would a food technology graduate want to be a forecaster?

“I grew up in Bicol region where there’s always a storm. It’s part of our system,” he remembers saying.

Days after the Metro Manila lockdown, Ariel developed symptoms so he had to strictly stay at home, fearing it might be COVID-19.

“It makes you go crazy and paranoid,” he says. But the symptoms stopped after a week and we was able to return to work albeit remotely.

Working for PAGASA, however, “leaves no room for tiredness and mistakes.”

“We are fortunate that Ambo was somehow short. If it drags on or another LPA or storm came close to it, it will consume too much of our energy,” he says.

The heavy rains and strong winds brought on by Ambo would end up affecting some 455,394 people who fled to evacuations centers in nine provinces in the country. The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) reported 169 people were injured. While they have listed no official casualty due to Ambo, media reports state that at least five people were killed during the onslaught.

Ambo would leave a total of P2.17 billion in damages. Some 25,000 houses and 336 structures, including hospitals and schools, would suffer damages. In Bicol, the only COVID-19 testing machine for the region would be destroyed.

As the wet season draws near, heavy rains, thunderstorms and even more typhoons are expected. Filipinos should prepare for more disasters in the middle of crisis brought by the coronavirus, which is expected to drag on at least until next year.

Although working in the new normal, PAGASA’s commitment to the nation remains the same.

“We will always be here for you. Rain or shine, pandemic or no pandemic, we are always here to serve you,” Chris says. “Please just listen to us and to our authorities for your safety.”