We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

WORDS BY KAELA MALIG

ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARGARET CLAIRE LAYUG

WEB PRODUCTION BY JANNIELYN ANN BIGTAS

March 9, 2020

Once upon a time, there was a game.

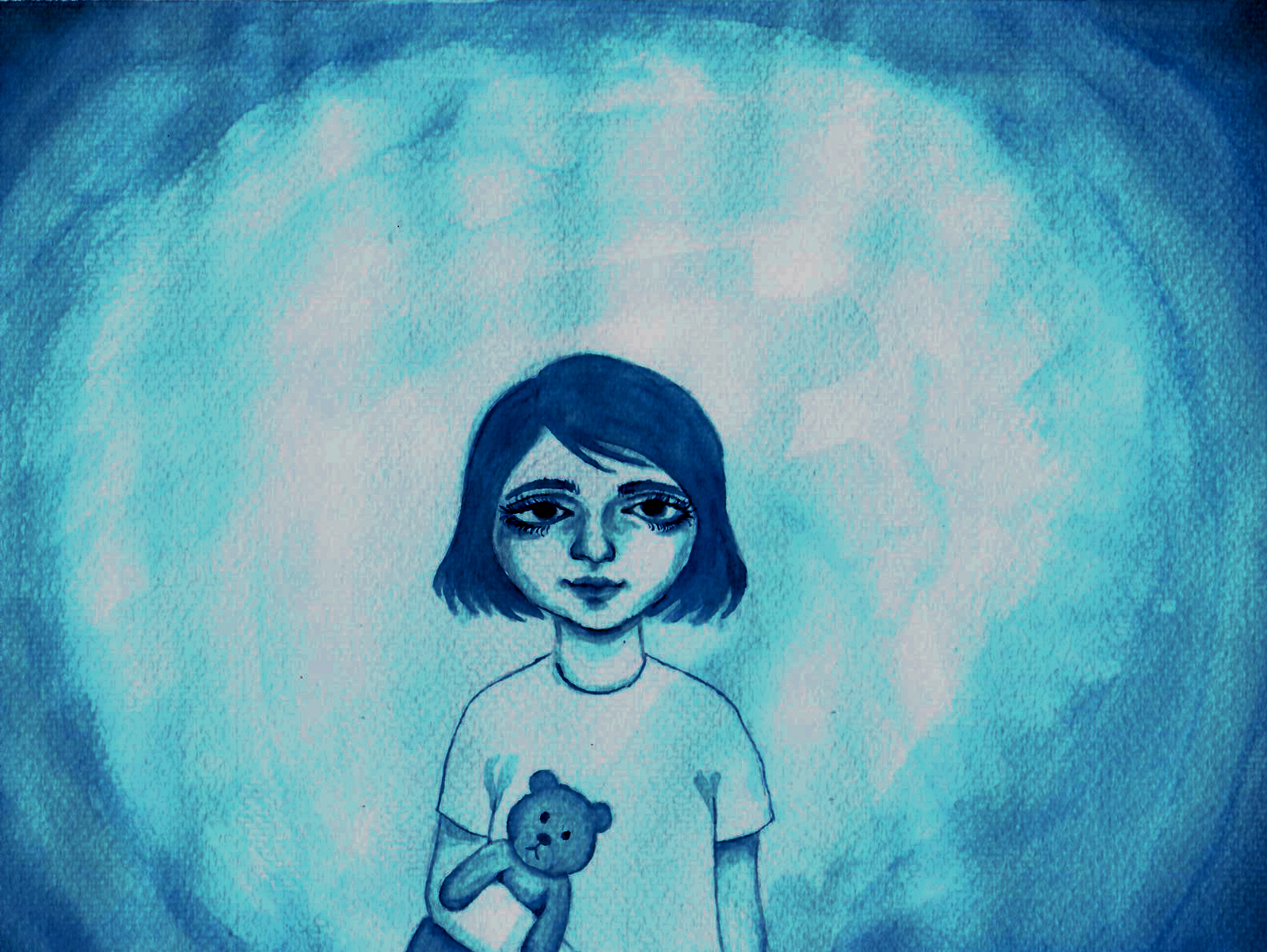

The game had no name, Abegail remembers, but it did have strange rules. It involved a knife to her side, doing exactly what she was told, and the unmistakable stillness of the house whenever her parents were away.

She was just four years old at the time, and even though she barely understood anything, her uncle made her understand the most important rule of the game: Don’t ever tell another soul .

“He had a balisong, a folding knife. He would always tell me that he’d kill me, or my mother, or anyone I would tell. I didn’t really understand what killing me meant. Why would he kill me if we were just playing? But I would be scared every time he would threaten me,” Abegail says.

Her parents were always away, and Abegail was left as the oldest child among her five siblings.

She was only four years old, barely old enough to comprehend anything, let alone her uncle’s game. Little did she know that, while the game was anything but normal, it was something that would become common among the children in her village, played by the same man who played the game with her.

Nobody knew anything. After all, this was her father’s cousin. This was the uncle people never had a reason to doubt, the uncle who would go to church with them every Sunday, the uncle who lived with them for years, the uncle who oh so loved other children.

The years went by in a blur, and so did the game. There were no catchy tunes to remember in the game, no bursts of laughter, and above all, no running allowed.

For six long years, the uncle kept playing the game with her, and soon Abegail wasn’t the same shy toddler when the game began. She had become a 10-year-old with a story she never knew had to be told.

One sunny day, while Abegail was playing in the streets with friends, she casually mentioned the game she played with her uncle. An older friend overheard their conversation and immediately told her parents.

The next thing Abegail knew, she was surrounded by grown-ups from her local church, asked to describe the game she mentioned to her cousin.

She told them how the game was played, thinking nothing of it. But the adults, they knew.

Her uncle’s favorite game had a name. It was called rape.

Today, Abegail is 28. Sitting in a corner of the therapy room of her church, she looks frequently out the window, her eyes sorrowful but determined as she tells her story.

Sometimes, her voice comes out in a soft whisper, but it never quivers.

She’s all grown up now, and she’s starting to finally take up space. She is no longer the little girl from 24 years ago who wished nothing else but to disappear.

She opens up about how the end of her abuse was far from the end of her suffering.

Unfairly, the consequences of another man’s evil became her cross to bear, without consent, without a choice, echoing through the years.

Her father, for example, became livid when he found out the truth about what his own cousin had done to his daughter. Abegail’s dad then went on to beat her.

“He kept slapping me, so I had no idea if he was mad at me or at my uncle,” Abegail says.

The court hearings began, and before long, her father began to make appearances there. Abegail took this as a sign of his acceptance.

But these hearings, in a room full of adults asking a 10-year-old the same difficult questions over and over, soon started to morph into Abegail’s personal hell.

“When the case started, I felt like it was all my fault because my mom and dad would always fight. There were even times when they would fight while waiting outside,” she says.

“Maybe because during that time we’d be in court the whole day, or almost every day because we needed to be there. Maybe they didn’t have time for my other siblings or time to do other things. All their time was focused on the case.”

In her dreams, Abegail had no escape. She was forced to play the game with her uncle again and again, until her mind would take pity and wake her up from yet another harrowing nightmare.

Memory, she says, was one of the hardest things to process. Despite her uncle being locked up in jail and long after she no longer had to go to hearings, her memory of the abuse remained a prison, one from which she could not break free.

When she was around 12 years old, Abegail and her mother went to the Philippine General Hospital to see a psychiatrist. The sessions didn’t last long. Every time Abegail and her mother would see the doctor, it was her mother who would get emotional and cry. Her doctor wrote her off as perfectly fine despite undergoing six years of sexual abuse at the hands of her uncle since she was four.

“I was ‘OK,’ I was ‘normal,’ so they stopped the processing. They told me that my mother was the one who needed to be processed more,” Abegail says.

What that doctor didn’t know was that for years, Abegail hated herself. She couldn’t look at herself in the mirror and could barely stand getting her photos taken.

Abegail’s case may be heartbreaking, but it’s far from uncommon.

According to the 2016 National Baseline Study on Violence Against Children in the Philippines published by UNICEF, 17.1 percent of children between 13 and 18 years old have experienced sexual violence while growing up.

That figure may even be lower than the actual number, as perpetrators are usually members of the family and their crimes may go unreported, says Eric Mallonga, a lawyer and child rights advocate who helped organize a task force on child protection and child sexual abuse during his stint at the Department of Justice.

“A lot happens at home and most perpetrators are family members, fathers, brothers, uncles,” Mallonga says. “And a lot of that is settled and so it’s not reported anymore.”

Fear and stigma also play a big factor why sexual abuse of children are underreported, says Zeny Rosales, executive director of the Center of the Prevention and Treatment of Child Sexual Abuse.

According to the UNICEF study, only 11.9 percent of sexually abused children disclosed the incident to someone. Most of them told either their friends or their mothers.

But even when children tell an adult, authorities are often not brought in out of fear and shame.

Rosales enumerates the usual reasons why families choose not to come forward about incidents: “‘If you tell the police, they might come after us.’ ‘It’s expensive.’ ‘We should just stay silent.’”

Overcoming all of that is a huge step for victims of rape, says Clara Rita Padilla, a lawyer who serves as executive director of EnGendeRights, a women’s rights organization.

“Whether or not you win, I would say that the mere filing, the mere standing up and say that she was a rape victim survivor is already one way of transcending from victim to survivor,” she says.

Even beyond that, the quest for justice remains arduous.

Abegail only found justice in August 2019, almost two decades after she first filed her case.

She isn’t quite sure why it took so long, but she remembers that when she was being interviewed by barangay officials, her uncle fled and went into hiding.

Even though her medico-legal examination confirmed her account, it did not help that there were no witnesses.

It was Abegail’s mother who was dogged about following up on the case, always attending hearings. Abegail’s own interest in the case turned lukewarm when her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer; by the time her mother died in 2015, Abegail had almost completely lost interest in the whole thing.

“You already have a wound, and they keep opening that up,” she says of the judicial process. “The wound deepens further each time you tell the story. Every time there’s someone new on the case, they’d ask you the same questions, and you would have to tell the same story, this time with more elaboration. Sometimes they would be insensitive when asking questions, that would add to the pain.”

It was a big relief for her when the case ended with her uncle finally convicted. After 18 years of waiting, Abegail’s suffering finally felt like it had amounted to something.

Jasmine remembers the paralyzing fear she felt when she was just 16 years old, as her mother’s boyfriend raped her in the bathroom.

Her mother had been working as a stay-in helper in another city. Her boyfriend, an electrician, would rip Jasmine away from her bed in the middle of the night to rape her, forcing her with the threat that he would do it to her younger sister if she didn’t go along.

“I would tell him he could do anything to me, just don’t do it to my sister,” she says.

Jasmine told her mother, who refused to believe a single word.

It wasn’t until after an aunt asked what was going on that Jasmine broke her silence and told everything. After Jasmine filed a report with her local barangay, her rapist was arrested the same day.

Jasmine found help from the Women’s Care Center, Inc. (WCCI), a shelter that gave her refuge. They discouraged her from seeing her mother for a year, fearing she would convince Jasmine to drop the case against her stepfather.

The shelter provided everything for her, Jasmine remembers, including help from a lawyer from the Public Attorney’s Office.

Because her mother would not be present at all during that time, it was her lawyer who took up the cudgels for Jasmine.

Years later, she could no longer remember the name of the woman who fought for her, but Jasmine could never forget how she gave her strength during one of the most critical moments of her life.

“She did everything. She was like a mother,” Jasmine says. “All in, defender, everything.”

At the shelter, Jasmine met other survivors of child sexual abuse. Like her, they also did not find support from those closest to them.

“They were afraid. The first problem there is the mother, if they didn’t listen to them. The others would reverse themselves, taking the side of their husband, which is why other children give up hope,” she says.

Mallonga, the lawyer and child rights advocate, says there are times when cases are filed and mothers would suddenly sign an affidavit of desistance. Some don’t want their husbands to go to jail, because they were the source of the family’s livelihood.

For others, blood is enough to look the other away from the crime.

This is a critical choice for victims of incestuous rape, because one of the most important factors for the healing of a survivor is the presence of a strong support system.

“That’s when the victims doubt whether they should report or not because they know it’s their relative, it’s their father, their brother, their grandfather. They’ll second-guess themselves and think that this is my own blood and I’ll send my own blood to jail. That’s one of the hardest things for the victim,” says Jojo Guan, president of the Center for Women’s Resources, a research and training institute.

Jasmine found that support instead from her lawyer, who gave her meticulous training for the battle ahead.

“She would tell me to come to her office early. I’d study my testimony, we’d be there all day until the hearing, we’d be together,” Jasmine says.

It only took a year after her report for her rapist to be found guilty. Still, Jasmine couldn’t help but feel sorry for him. He had been beaten up badly in prison, his face full of bruises when she saw him in court. He looked so old and weak, Jasmine remembers, and her heart sank.

“It really broke my heart, I even started clutching the skirt of my lawyer,” she says. “But then she’d tell me, ‘Why would you feel sorry? You were the one who was hurt.’ That gave me strength to push on.”

Jasmine remembers how he wouldn’t even look at her during court hearings. He never, not once, professed an apology or admitted to anything.

These days, Jasmine doesn’t know whether her stepfather is still alive, but if he is, she knows he will spend the rest of his life rotting in jail.

Reflecting on why he thought he could get away with it, Jasmine says: “Maybe during that time I couldn’t do it. I didn’t have the strength to tell anyone. He thought no one would help me.”

It turns out he was dead wrong: there were people out there who would help her.

Even though Jasmine found justice relatively quickly, the trauma still had its effect on her.

She wasn’t alone in the pain; some of her friends from the shelter would even cut themselves, she remembers.

Jasmine, for her part, was scared of everyone. “It’s like you’re going crazy thinking what you’d do if people wanted to talk, because you don’t have any self-confidence,” she says.

To this day, outside the shelter and her family, only her husband knows about her past. “It’s different from the outside. They look at you differently. If you’re inside, if you’re in the shelter, you understand each other. You understand what everyone went through. If you tell it to someone from outside, it just feels like gossip,” Jasmine says.

It once got so bad that when Jasmine was getting counseling sessions from a psychologist in East Avenue Medical Center, she would occasionally think of jumping off the building to end her life.

But then, she finally caught herself. “Why would I jump? This isn’t the ending of your life. This is just the beginning. That’s when it all started to sink in.”

At 11 years old, Jessy would wake up in pain in the middle of the night, her shorts and underwear pooled around her knees as her father lay on top of her, pinning her down.

When her mother finally found out about the abuse, she came home from Singapore and took Jessy and her siblings away. When they were able to file a case against Jessy’s father, his relatives went to Jessy to ask her not to go through with it.

“My aunts would beg me. It wasn’t until then that they found out what happened, but they wouldn’t believe me. My father was a kind man; even I could not believe he could do that to me,” Jessy says.

Jessy had grown up thinking of her father as a nice and responsible man — far from the heinous monster he would turn out to be.

Everything changed when Jessy’s mother left him after finding out that he had cheated on her. She had to fly back to Singapore to make a living for her four children, while he remained jobless.

After that, the stench of alcohol would follow him everywhere like heavy perfume, dousing him as he drank from day to night until he was too exhausted to even lift another bottle.

What happened next — and what happened again and again in the middle of the night — remains etched in Jessy’s memory.

“It was dark, and I couldn’t move because I was so scared, so I couldn’t fight back,” Jessy says.

The eldest among her siblings, Jessy didn’t know who to turn to for help. She didn’t have a lot of friends at school. Most of their neighbors were also relatives of her father. Her mother was still in Singapore.

Jessy felt like she didn’t have any choice but to keep it all to herself. If she left, where would she go? What would happen to her younger siblings if she was gone? At a young age, Jessy was burdened with a life-changing decision no child should have to make. She decided to stay for a year and endure the pain every night as she waited for her mother to come back home for good.

Finally, Jessy’s elementary graduation was coming up and her mother’s sister came to help her prepare. Immediately, Jessy’s aunt saw just how much the young girl had changed.

“She said I had no energy, something I didn’t notice about myself,” Jessy says. “She said my body had changed… I gained weight.”

While Jessy did not open up to her aunt, stories about the change in the child reached her mother. From Singapore, she immediately called Jessy up, and the girl finally told her mother everything.

Jessy could still remember the last time her father raped her: March 31. Her mother flew back as soon as possible. By April 9, she had taken away all of her children and reported her daughter’s case to the barangay. Jessy’s father was arrested on the spot.

Even then, the fight would be far from over for Jessy. At the hearings, her father’s lawyers would badger her about her years of silence, asking why she never told anyone, why she never fought back, even though her father had never taken a gun or knife to her.

“It was hard to explain that it was because you’re full of fear. You can’t even begin to explain it because when you go to court, they only look at physical evidence. The emotions you went through are disregarded no matter how many times you tell them that you did not tell anyone because you were scared. That’s the only thing I kept saying,” she says.

Experts note that there remain problems within institutions in the country when it comes to processing rape cases, specifically when it comes to the burden of proof.

“For example, if someone is beaten up on the streets, you don’t ask that person, ‘Why were you beaten up?’” says EnGendeRights executive director Clara Rita Padilla.

“You just accept the fact that the person was beaten up. You just ask how he was beaten up and not why. But in terms of rape cases, unfortunately, it seems that some people in the prosecution office in the courts place the burden of proof on the woman.”

In 2005, a rape survivor, Kara Vertido, lost a case at the regional trial court. She brought her case up to the United Nations Committee on the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, which ultimately ruled that the Philippines should review its laws on rape and center it on lack of consent.

“So if you say lack of consent, the burden will be on the perpetrator, whether he really asked, in what means, in what ways he really sought the consent of the woman, and if you cannot prove the consent of the woman then definitely he fails in proving there was consent rather than placing the blame on the woman,” Padilla says.

The problem lies not just in the process, but the people as well. According to Padilla, there are prosecutors and justices who still subscribe to “a patriarchal view where they feel it was consensual when it was definitely not.”

In a more just world, Jessy would have had all the evidence she needed to prove her father deserved to remain in jail. After all, her medico-legal examination showed that she had been raped.

Unfortunately, it was not the only test that would turn up positive for Jessy.

Jessy was already 11 weeks pregnant when she told her mother that she was carrying her own father’s child.

“So that’s why they were saying that my body had changed, it turns out that I was pregnant at 12. I did not know what the signs of pregnancy were, so I had no clue. I would throw up every morning, I would be nauseated, I was being moody… but I didn’t know those were signs that I was pregnant,” Jessy says.

Jessy’s case is far from isolated. The incidence of pregnancy is on the rise among girls aged 10 to 14 in the Philippines, according to the Commission on Population and Development (POPCOM). Romeo Dongeto, executive director of the Philippine Legislators’ Committee on Population and Development Foundation, Inc. (PLCPD), says sexual violence is connected to this meteoric rise.

While there is currently no available government data detailing how many of the teenage pregnancies in the country are connected to sexual violence, POPCOM notes that from 2011 and 2018, 130,000 babies from teenage pregnancies were fathered by men who are 20 years old and above.

POPCOM Undersecretary Juan Antonio Perez III notes that while the data is alarming, they are seeing few rape cases being filed. “I think we need to empower the local goverments, the civil registrars, when they see children giving birth, we hope there would be action,” he says. “I think our local governments who see these cases should be helped to file suit in these cases, so we have to be more vigilant when it comes to children at these ages.”

Women and children’s rights groups have also urged lawmakers to raise the legal age of sexual consent in the Philipines to 16 years old, from the current 12 years old. The current age of consent, according to the Philippine Commission on Women, leaves children “vulnerable to sexual predators especially those older than them and who may take advantage of their impressionability.”

At first, Jessy thought about having an abortion; going through with her pregnancy put her life at risk, because there was no assurance that her barely adolescent body could handle the process.

Police officers, however, convinced her to keep the baby, saying it would be strong evidence against her father. His relatives, after all, had insisted that they saw another man in the house who could have been the father of Jessy’s unborn child.

It still wasn’t enough to keep her father locked up. Three months after court hearings started, he was released from jail.

“From what I remember, it was because of illegal detention,” Jessy says. Her father’s lawyer successfully argued before the court that authorities were unable to file a case within 48 hours of his arrest.

Her father would then attend two more court hearings before he completely disappeared — not just from her life, but from the case.

While he was set free, Jessy was brought to a Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) shelter in Alabang, then to a public hospital in Manila when it was time for her to give birth. She went into labor that lasted the entire day. The only thing she could remember was feeling so much pain that she thought she was going to die.

“I was telling my mother, ‘I can’t hold on.’ I told her I felt like I couldn’t breathe. I didn’t know which part hurt most. My mother was in a panic,” Jessy says.

Her water wouldn’t break, so doctors had to insert something inside her to break it manually.

By the time she was about to deliver, there was no one to hold her hand. She was told no one was allowed inside the labor room, the delivery room, or even the recovery ward, because there were so many other pregnant women.

In October 2004, 13-year-old Jessy was all alone when she gave birth to a baby boy at the break of dawn.

“When I got to the ward, visitors weren’t allowed inside. They could only stay outside and couldn’t give you your food. You’d have to walk to your guest to get the food they brought you,” Jessy says.

After the baby was born, Jessy’s mom tried to take care of him, knowing he had nothing to do with his father’s sins. But because she still had three other children to feed, Jessy’s mother couldn’t afford to raise another child.

After arranging documents with the DSWD, Jessy gave up her baby to a convent in Malabon. That was the last day she saw her child.

Despite Jessy giving birth to a baby, her father — both her and her baby’s father — walked free. He remained a free man until the day he died in 2006.

Jessy heard the news when her mother came to visit her at the shelter. He died in an accident while selling fish on the streets in Caloocan. He had another family and had even welcomed a new baby just before he died.

Jessy could not understand how it was possible that he never faced any consequences while she continued to live in the shadow of his crime.

“If he could sell fish in the streets then that meant he was out in the open, and yet no one arrested him?” Jessy asks in disbelief.

While her father basked outside, Jessy transferred from one shelter to another. She moved to a private convent in Malabon before transferring to Marillac Hills, Alabang, then to St, Mary’s, Tagaytay.

She entered the shelter when she was 12 and was only released to the custody of her mother when she was 16. Although Jessy is grateful for the protection and healing the shelters gave her, she couldn’t understand how she remained under close observation while her father, who she knew was a criminal, was free the whole time.

She laments how easily her father had gotten bail approved despite a pending heinous crime case. She suspects it had to do with the close ties of her father’s relatives to government and police officials.

“It’s like my stay was longer. I didn’t commit any crime, yet I was the one who was isolated, while my father was only in prison for three months,” Jessy says.

As the years turned into decades, the children have disappeared, and Jessy, Jasmine, and Abegail are all grown up. On the outside, they look like any other woman you may know. Still, through all the years of healing, some scars remain.

Jessy now works in an office in Manila. She doesn’t see herself ever getting married, but she still would like to have a child of her own one day. She would like a baby boy.

He never asked for it, but Jessy has already given her father her forgiveness. “I forgave him when he died, when I first stepped inside and saw his coffin,” Jessy says. “I told him he could take it with him since that’s the only thing I could give.”

Abegail finished taking up her teacher’s licensure exam last year. To this day, she remains scared of men, fearing even the barest touch from them. “There are times when I would shake every time a man would touch me, but lately I’ve been doing OK,” she says.

It wasn’t until 2017 when Abegail decided to get counseling for herself. Abegail says she’s still in the healing process. She was only recently diagnosed with depression and is finally getting treatment.

There has been a breath of fresh air. The process has been grueling, but she has come to learn, slowly, to appreciate herself. These days, Abegail is finally able to check out her reflection in the mirror and even look at herself in photographs.

Jasmine has reconciled with her mother, who expressed regret about her decision in the past not to believe her daughter. She is planning her wedding. She and her boyfriend have been together for 10 years, and Jasmine considers him her husband, just without the papers. Together, they have a boy who is in grade school.

The three women march on with their lives, carrying from their childhoods a heavy burden unbeknownst to the rest of the world. Some days are better than others. Still, they trudge ahead, hoping that someday, there would be no more games to play.

If you or someone you know has been a victim of sexual abuse, please do not hesitate to contact the following for assistance:

Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Child Sexual Abuse - (02)8426-7839

Women Crisis Center - 0928-420-0859 / 0999-577-9631 / 0916-246-7470

NBI Anti-VAWC Division - (02)8525-6028 / (02)8523-8231 to 38 loc. 3444

SHARE THIS STORY