We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

At eight years old, he would pair up with his cousin whenever they played hide and seek. Because he was younger, he would follow everything his cousin told him to do.

“Don’t make any noise, or they might catch us,” his 14-year-old cousin would tell him.

While hiding from their playmates, his cousin would touch his chest, grope his crotch, and whisper in his ear not to tell anyone. They were simply playing a game, his cousin would remind him.

Karl would believe him, of course. It was all he could think about every time he saw his cousin. Later on, two more cousins would join in on the “fun.”

At that tender age, he already knew what sex was. He learned how to pleasure another man even before he learned about the reproductive system, which was taught in the latter years of elementary school.

This “game” would go on for years.

“I grew up religious, so I struggled at that time. A big part of me was confused because everything I was experiencing was different from what the Church taught me,” he said.

“Growing up, I never identified as a straight man because I was immediately attracted to men.”

But “playing” with his cousins would soon take a dark turn.

“My cousin would tell me, ‘If you won’t do it, I’ll tell your family about this. I’ll have your parents killed.’ They were threatening me, so I was forced to do those things.”

By the time he was 20, Karl was living a life of sexual promiscuity. He would dial random numbers in his pager, call random people to try to strike up sexual conversations.

He became more adventurous, staying late inside movie theaters when fewer people would watch, just so he could perform oral sex in the dark with strangers.

During his morning exercises, he would hook up with fellow joggers near the banks of Marikina River.

It reminded him of how everything started: behind the trees.

“It’s a fulfillment for myself. It boosted my morale. I felt like I was handsome even though I’m not,” he admitted.

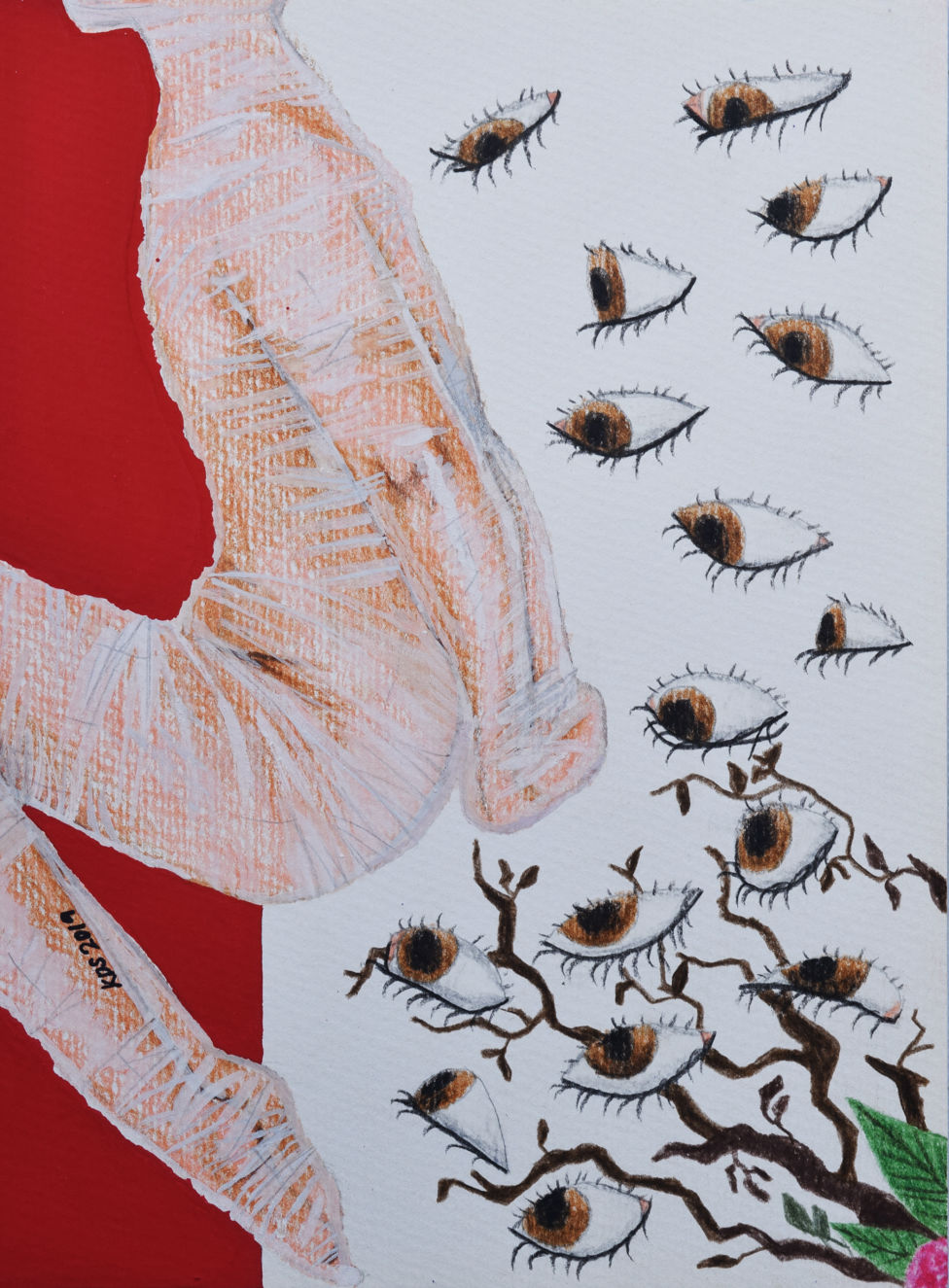

But the boost in self-worth would prove to be temporary. One day, rashes slowly formed in his arms. They spread to his face, attacking not just his skin, but his self-esteem.

“I felt ugly. I had plenty of rashes that I felt sick just by looking at myself. I became depressed, I shied away from people, and I couldn’t go to work. I didn’t want anyone to see me because I felt guilty and disgusted with myself. A part of me is telling me that I was being punished by God. This was the consequence of everything I did in the past,” he said.

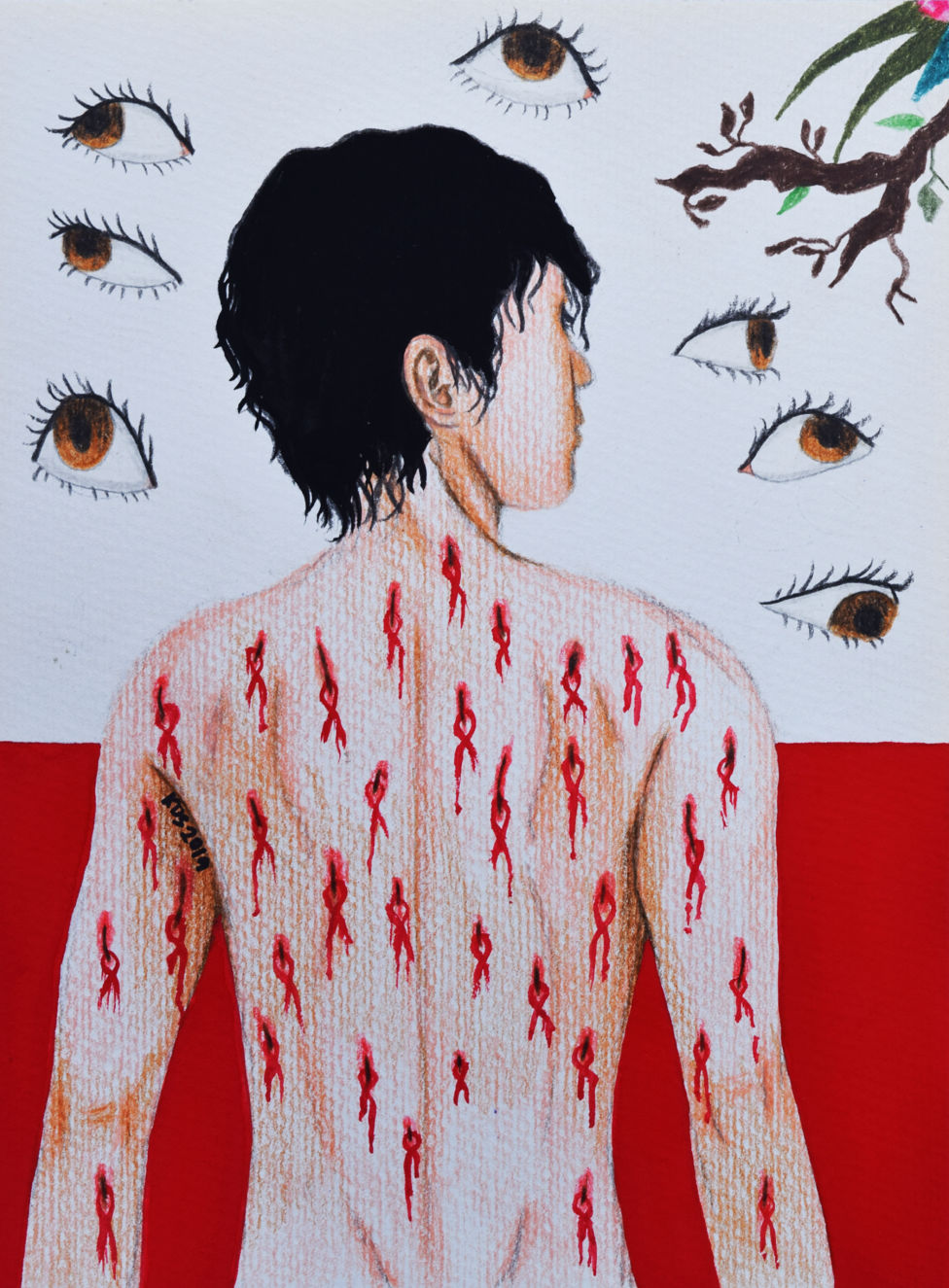

He went to the doctor to have himself tested, expecting the worst. After a month of beating himself up and isolating himself from everyone, it was confirmed: he had Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

With the truth dawning on him, Karl knew exactly where to direct his ir.

“I blamed my cousins because of what they did to me. I wished they would just die. I wished they got hit by karma. I wanted revenge because I knew that I shouldn’t be the only person suffering from this virus. There are so many people who have unprotected sex and with all the people I’ve had sex with, it’s very unfair that I’m the only one experiencing this.”

But Karl is far from the only person with the experience. The Philippines is one of the countries with the fastest number of HIV patients in the world. According to Department of Health data, daily HIV cases have grown exponentially, from one to two daily cases in 2008 to 13 daily cases in 2013. By 2015, there are already 22 cases reported daily. This has ballooned to 32 cases by 2018.

“It is always alarming because of the increase. The rate of increase is one of the highest in Southeast Asia. It is about 144%,” Health Secretary Francisco Duque said in September.

Karl himself was at particular risk. DOH data shows that male-to-male sex (MSM) was the number one mode of transmission for HIV.

“Anal sex can cause more mucosal injury, so the anal walls tend to bleed. This kind of sexual contact allows a higher chance of transmitting the virus,” Infectious Diseases Specialist Dr. Daisy Tagarda said.

Still, men having sex with men are not the only ones affected by the HIV epidemic. DOH data shows that about 11 percent of the daily cases of HIV recorded in May 2019 were from sex between males and females.

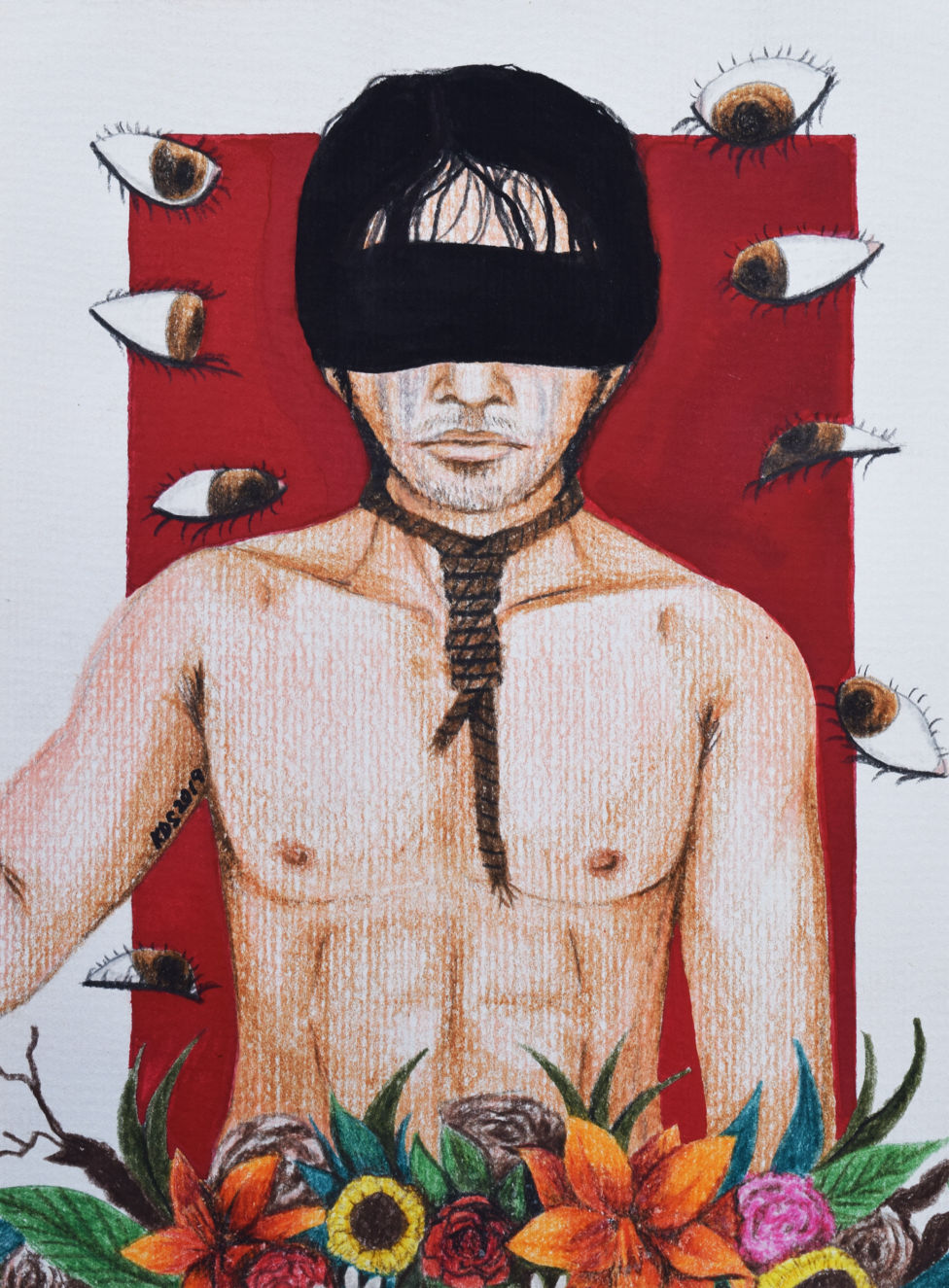

This was the case for Mharo. At 27, he did not think he would ever contract what a hysterical world had once perceived as “gay cancer.”

Growing up estranged from his parents, Mharo began sleeping with older women as a call boy in 2016. It was his twisted way, he said, of experiencing motherly love.

“I met an older woman who took care of me and gave me financial support. I’d ask her a minimum of Php 10,000 every night so I could buy a laptop or a cellphone. Everytime she gave money, I’d have to return the favor by having sex with her.”

Mharo would soon feel his body becoming weak. His eyes sank in deep dark circles, his collars became more prominent, his appetite decreased every day, and every mouthful of food he took came back out.

He had to visit eight hospitals before doctors could identify his disease. The woman he was sleeping with admitted that it was her who had given her HIV.

Upon learning the news, Mharo attempted to kill himself on three separate occasions. Each time he survived, he would burst out in fury because he wanted nothing but to die.

“I found it more difficult to accept my fate when the doctor said I won’t be completely healed. Even if there were medications available, it can only help prolong my life. I was more worried because that meant I had to live with this disease forever.”

His suicidal thoughts evolved into rage. A few months after finding out his status, he began a romantic relationship with another woman. He purposely had unprotected sex with her, and she became pregnant. Four months into the pregnancy, she found out about Mharo’s status and had an abortion.

“I was confused. I told myself that if other people managed to infect me with this virus, then it might be a good idea to pass it on to someone else too. I thought — I should have sex with someone without protection, so I could spread the virus.”

The anger felt by victims of HIV is brought on in large part by the stigma that the illness still carries to this day.

Mharo himself was witness to this.

“There were rumors in our place that there was someone with HIV who died. He was wrapped in scotch tape and people were disgusted. That made me even more scared. I thought that this would be my fate if they found out about my condition. I asked my dad to keep my status a secret,” he said.

Healthcare professionals and advocates have sounded the alarm about the need to change this perception.

“Not everyone is willing to listen. They have their own preconceived notions about what HIV is. With further education, like what HIV-awareness organizations are doing, we can enlighten these people and address the stigma attached to the virus,” Dr. Tagarda said.

Eliminating that stigma is critical, because aside from the high growth of cases, people living with HIV (PLHIV) are getting younger.

“The predominant age group among those diagnosed has shifted to 25-34 years old starting 2006 from 35-49 years old in 2001 to 2005. Further, the proportion of HIV positive cases in the 15-24 year age group nearly doubled in the past ten years, from 17% in 2000 to 2009 to 29% in 2010 to 2019,” a DOH report read.

The advent of technologies like social media and dating apps bring with it a new set of challenges.

“It’s easy to get sexual partners these days because of dating apps. Sometimes, sex happens through groups. With group sex, there’s a higher risk of transmissiting the virus,” Dr. Tagarda said.

But while social media can be a bane, it can also be a boon when it comes to educating the youth about HIV.

“Social media is important in spreading HIV awareness especially in this generation wherein most of the community are [getting] information online,” said Mhark Yahot, president of MARIPOSA Inc., an HIV support group.

“In order to promote a positive engagement about HIV awareness using social media platforms, we need to [encourage] Filipinos to visit the nearest social hygiene clinics. [We] believe that education is the best key to build connections to our society and social media will be our gateway to make this happen,” he added.

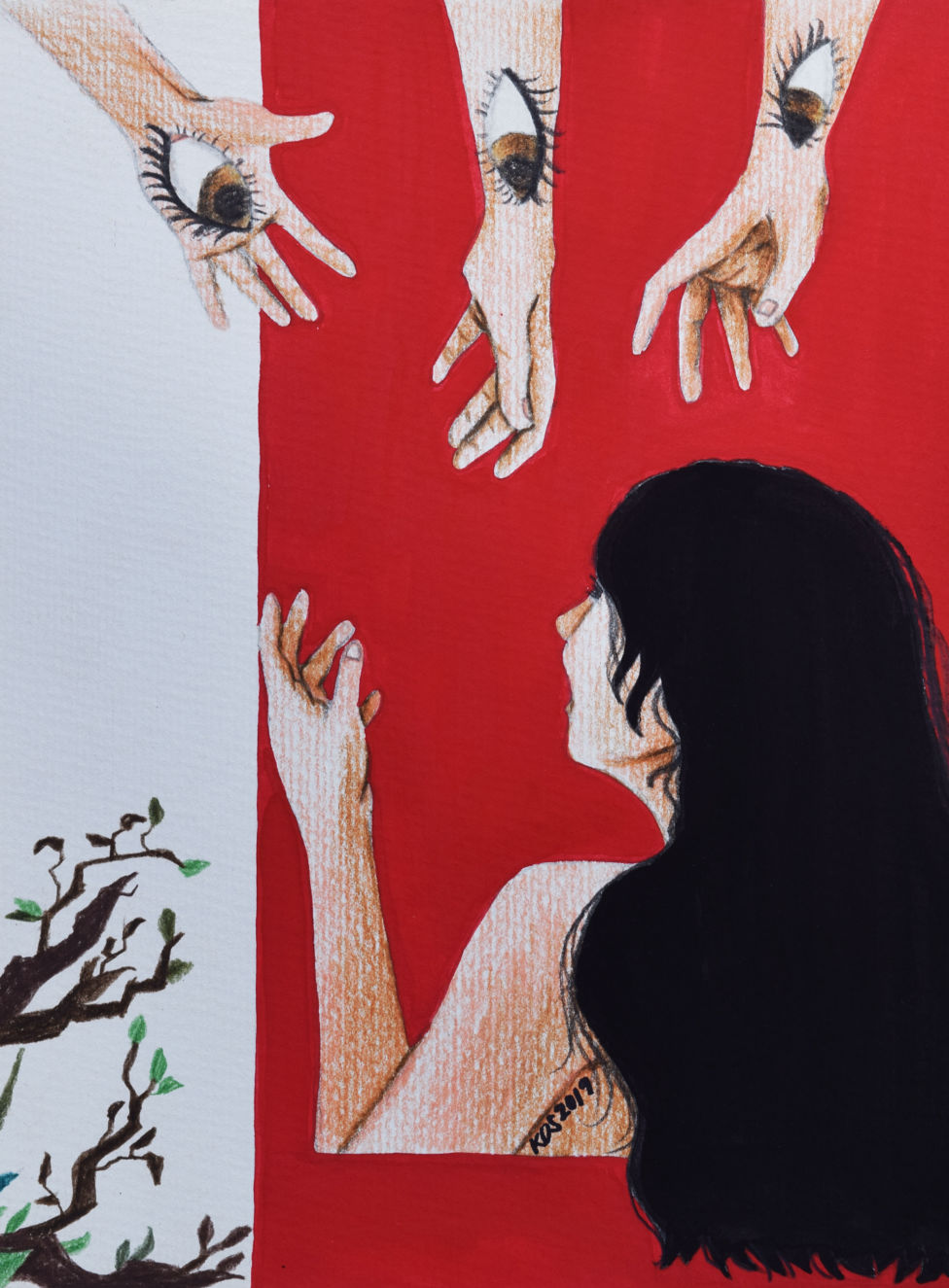

There is life after HIV. Karl and Mharo are both proof of that.

For his part, living with HIV remains difficult for Mharo. But while he admits that he hasn’t completely gotten over his traumatic experiences, he has sought the help of MARIPOSA, Inc. and now volunteers as the organization’s director for public relations.

“I noticed in MARIPOSA that there are women and children who also have HIV. That helped me realize that I wasn’t alone in this fight. There are many other people like me, so we really need to support each other.”

Now 42, Karl has joined Project Red Ribbon, an HIV-awareness group, and committed himself to spreading awareness and providing care for people living with HIV. His goal: to make sure that the virus ends with him.

“I will not waste this opportunity to become an advocate because I don’t want other people to go through what I’ve been through. They need to know that having HIV and AIDS is not easy. It’s enough that we have it. HIV ends with us.”