We use cookies to ensure you get the best browsing experience. By continued use, you agree to our privacy policy and accept our use of such cookies. For further information, click FIND OUT MORE.

A decade since the murder of 58 people, including 32 journalists, in the worst incident of election-related violence in the country, the families of the victims need to wait a little longer for the justice for which they have hoped for so long.

By NICOLE-ANNE C. LAGRIMAS,

GMA News

November 23, 2019

ON A NARROW ROAD in Ampatuan town in Maguindanao, a printed red arrow points the way to the site of a massacre known as the Philippines' worst incident of election-related violence.

Surrounded by tranquil hills, the earth there has been enclosed by a red fence and filled with markers containing the names of the dead, visited each year by the families they left behind.

Though its place in history is not lost on Xhandi Morales, the spot is best known to the teenager as the one where she violently lost a father a decade ago. She said the tears came before she even saw the site for the first time last year.

"'Di ko po talaga maintindihan [ang] nararamdaman ko," she said. "Hindi po talaga mawawala sa 'kin 'yung sakit na bata pa lang, kinuhanan na ng isang ama."

Xhandi, 15, is the youngest of three daughters of News Focus correspondent Rosell Morales, one of the journalists who died in the massacre that is also considered as the single deadliest attack on the press since detailed records were kept.

She was five years old when her father was murdered. Now a high school student, Xhandi's years of waiting are down to a few weeks, and she is certain a conviction is coming.

Judge Jocelyn Solis-Reyes has until December 20 to promulgate a decision on the multiple murder case against more than a hundred people she tried for more than nine years.

Andal Ampatuan Sr. is wheeled out of the Pasay Regional Trial Court after a hearing on an electoral sabotage case against him in 2012. The patriarch of the clan accused of masterminding the Maguinao massacre died of liver cancer in 2015.

GMA News File Photo/Danny Pata

CASE RECORDS

The events of November 23, 2009 have become familiar by now: Accompanied by media, relatives and supporters of Esmael "Toto" Mangudadatu were on their way to file his candidacy for the governorship of Maguindanao when they were stopped at a checkpoint and abducted by armed men.

Mangudadatu, vice mayor of Buluan town at the time, was about to challenge Datu Unsay mayor Andal Ampatuan, Jr., son of then-governor Andal Ampatuan Sr., in the 2010 gubernatorial race.

The members of the Mangudadatu convoy were reportedly forced up into the hills of Sitio Masalay, shot using high-powered firearms, and buried in shallow graves using a backhoe.

Fifty-eight people died, including Mangudadatu's wife and two sisters. Thirty-two of the casualties were members of the media, one of whom was never found. Six victims were not even part of the convoy.

Mangudadatu became governor in 2010. He is now the congressman for the Second District of Maguindanao.

READ: The victims of the Maguindanao Massacre

Ampatuan, Sr., the patriarch of the powerful political family, and his sons Unsay, Sajid, and Zaldy and 193 others were charged with 58 counts of murder. Fifteen defendants were surnamed Ampatuan, according to court records.

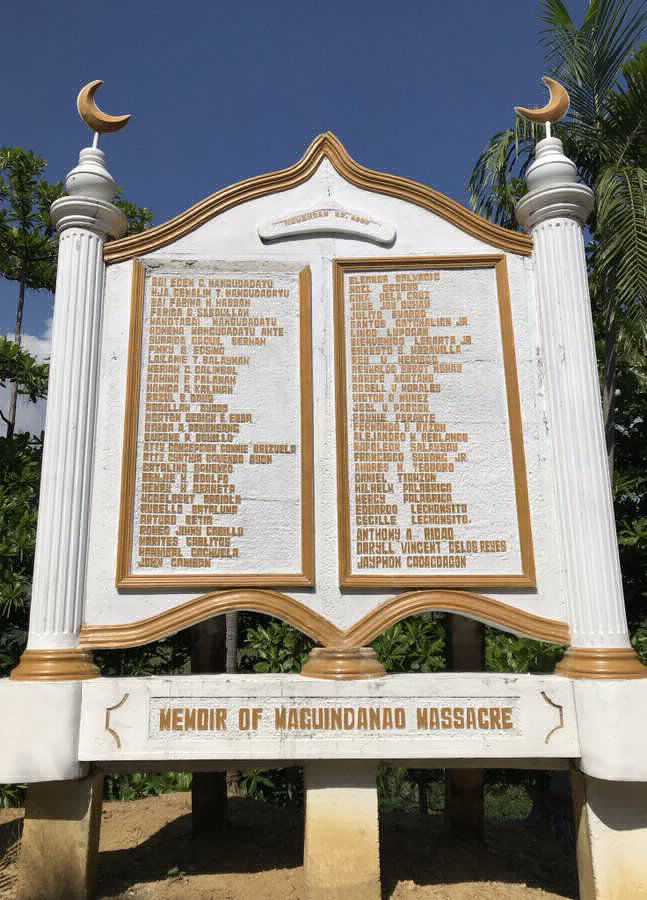

A marker for the victims of the Maguindanao Massacre, 20 of whom were Mangudadatu family members and supporters, 32 were media, and six weren’t even part of the convoy. The body of photojournalist Reynaldo Momay was never found.

GMA News/Nicole Anne C. Lagrimas

Considering these numbers, the trial of the century was expected to be lengthy; the late senator Joker Arroyo said it could drag on for 200 years. But Judge Reyes was done in less than a decade.

In more than nine years, she heard 357 witnesses — 134 for the prosecution, 165 for the defense, and 58 private complainants. The case records — transcripts of hearings, pleadings, and evidence — reached 238 volumes.

READ: Like anyone else, Judge wants an end to Maguindanao massacre case

Nena Santos, a private prosecutor representing dozens of the victims' families, attributes the length of the trial to numerous pleadings and changes in lawyers of the accused. As of October, the defendants had 20 lawyers or firms. Unsay reportedly claimed as early as 2014 that his family's resources were depleted by litigation costs.

On the other hand, the government was represented by 11 lawyers from its third panel of prosecutors by the time trial ended.

Of the original 197 accused, 80 remain at large. One defendant was cleared for lack of probable cause, another was dropped from the amended charges, two were discharged as state witnesses, and four were released due to insufficiency of evidence, court records show.

Eight of the accused have already died, including Andal Sr., who succumbed to liver cancer in 2015.

Out of all the people arraigned, 101 were left when trial wrapped up this year. The case was submitted for resolution on August 22. Under court rules, the judge was supposed to have rendered a decision by November 22, but she requested an extension and was granted 30 more days by the Supreme Court.

Though an incident of a similar scale has never occurred since, the number of killed journalists continues to rise.

Excluding the Maguindanao Massacre, which appears in the data as a category of its own, the Presidential Task Force on Media Security has recorded 27 work-related killings of journalists since 1986 that are undergoing trial or investigation.

Sixty-four other cases, 13 of which are work-related, are considered "closed." The data shows there were convictions in 16 cases. Fifty-five cases were not work-related, the task force said.

In total, the task force has counted 178 killings of journalists in the last three decades, according to data provided to GMA News Online. It received 56 reports of threats and found that seven journalists survived attacks.

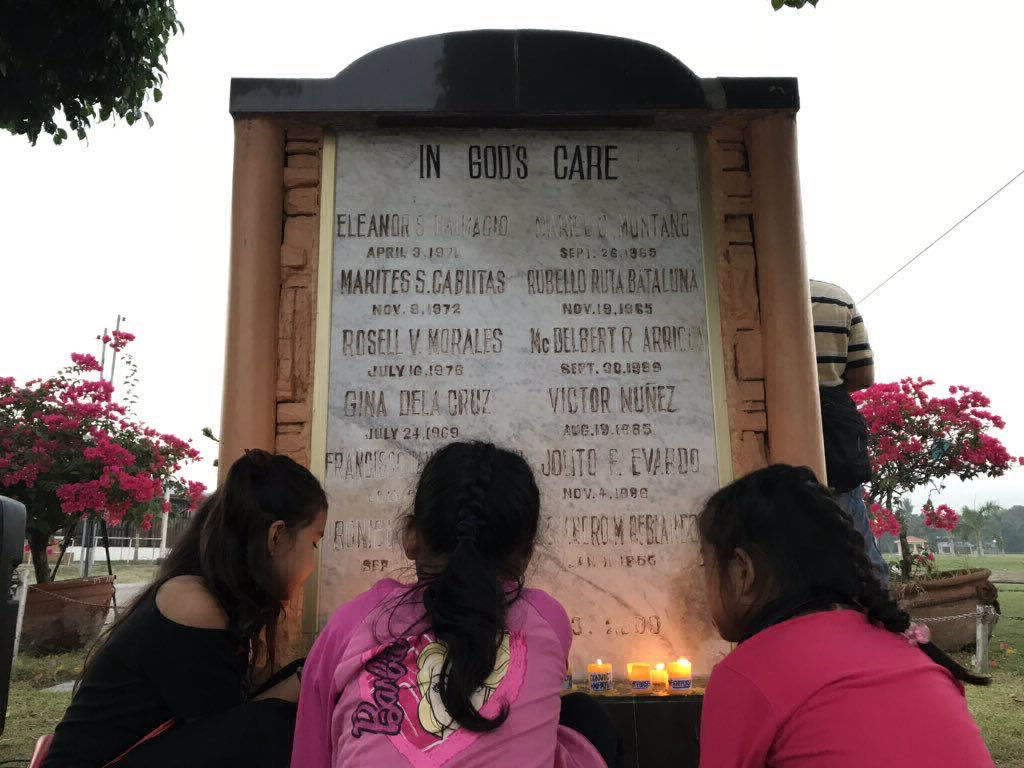

Three girls who were months old when their parents died during the Maguindanao Massacre visit a memorial to the victims of the 2009 mass murder in Ampatuan town, Maguindanao on November 17, 2019.

GMA News/Nicole-Anne C. Lagrimas

Bonded by a tragedy, the children of the victims of the infamous massacre in the hills of this town have learned to cry for justice even before they were old enough to know what the word means.

"Nag-aapoy ang mga dugo, wasak na wasak man ang aming puso, 'di pa rin kami susuko, ito'y pagsubok lang—hustisya," they sang at a covered court overlooking the massacre site in Sitio Masalay, forcefully delivering a tune written by one of their own when she was 15.

One of the more passionate singers, 11-year-old Kai Kai, later admitted she does not know what "justice" is, but described in no uncertain terms a life without a mother: "Masakit, malungkot."

Eleanor Dalmacio, a reporter for Socsargen News Today, was one of the journalists who traveled to the town on the morning of November 23, 2009 to cover the filing of then-Buluan vice mayor Esmael "Toto" Mangudadatu's certificate of candidacy for the 2010 gubernatorial race.

She and 31 other members of the media were in a convoy with Mangudadatu's wife, sisters, and supporters on their way to the filing when around a hundred armed men stopped them, forced them up the hills, and shot them using high-powered firearms.

At Forest Lake Cemetery in General Santos City, where her mother and 11 other victims are buried, Kai Kai complies when asked to read aloud the words on the candles she and her friends have been playing with: "Convict Ampatuan." "Justice now."

The songwriter, Faye, and her two sisters were also at the cemetery to light candles for the victims, including their father Rosell Morales, circulation manager and correspondent for News Focus.

The oldest of Rosell's girls, 20-year-old Nicole, was only nine at the time of the massacre.

"Hinihintay na lang po kasi namin 'yung desisyon... pero hindi po natatakpan 'yung sakit na nararamdaman namin kasi hindi mababalik 'yung buhay ng mga mahal namin sa buhay," she said.

Xhandi, the youngest at 15, admitted that staying the course is difficult after 10 years. "Nawawalan na rin kami ng lakas ng loob," she said.

But every year, she said, the children get together for workshops on activities like painting and poetry writing.

"Nakakatulong po sa amin na maparating sa ibang tao yung mga nais naming iparating na gusto talaga namin ng hustisya para sa mga mahal namin sa buhay."

Nicole Morales was only nine years old when her father, journalist Rosell Morales, was killed. She is waiting for the court judgment on the multiple murder case, but says nothing can bring her father back.

GMA News/Nicole-Anne C. Lagrimas

FORGIVENESS?

Maguindanao congressman Esmael "Toto" Mangudadatu may have said he has forgiven the men who killed his wife and two sisters, but forgiveness remains a difficult topic for Nicole, Xhandi, and their mother, Mary Grace.

"Kung ako ang tatanungin, salitang patawad pwede namang sabihin," she said. But the anger would be hard to take away without the perpetrators paying for their crime, she said.

"Siguro mapatawad, pero matagal, at kailangan nila talagang pagbayaran," Mary Grace said.

For others, however, forgiveness is a way out of the burden they have carried for a decade.

Elliver Cablitas, the husband of News Focus publisher and anchor Marites Cablitas, said visits to the massacre site and interviews only make him remember the pain of having to retrieve his wife's body from the hill.

"Ako papatawarin ko na 'yung mga Ampatuan, sa totoo lang, pinapatawad ko na sila, pinabahala ko na sa Diyos," he said. "Alam mo 'yung pagpapatawad, mawala 'yung heartache ko, sama ng loob ko sa kanila."

He wants a conviction for all the accused, but said former Datu Unsay mayor Andal Ampatuan, Jr.—who allegedly killed victims himself—is "number one" on his mind.

The families of the victims of the Maguindanao Massacre continue to call for justice 10 years after the gruesome murder.

GMA News/Nicole-Anne C. Lagrimas

A JOURNALIST'S DAUGHTER

Sitting at the edge of the covered court overlooking the sprawling hills not unlike the one her father was murdered on, Xhandi reads a Bible verse taped to the page of a school book. She said this was for the skit they performed at the program.

The 15-year-old remembers visiting the massacre site for the first time last year and crying before they even went up the road leading to the spot, where markers for the dead have been put up.

Though her goal is to become an accountant, Xhandi is interested in reporting and is taking up a broadcasting class. Her sister Nicole, an education major, wants to become a lawyer.

Xhandi said she does not fear being a journalist despite her father's murder.

She has no doubt the killers will be convicted. But what if they aren't?

"Hindi kami titigil," she said.

AMPATUAN DEFENSES

According to prosecutors, the Ampatuan family planned to kill Toto Mangudadatu, who belongs to the family of their political rival, over a series of meetings in July and November 2009.

The first meeting was allegedly held at Century Park Hotel in Manila on July 20; the subsequent ones in Shariff Aguak in Maguindanao on November 16, 17, and 22, according to court documents.

The Ampatuan brothers — Unsay, Zaldy, and Sajid — have all sought to be acquitted using different alibis.

Unsay, who allegedly killed some of the victims himself, claimed he was on a flight to Manila from the United States on November 17, landing on the 18th and traveling to Cotabato on the same day. An officer of the Philippine Airlines corroborated this, according to his memorandum.

On the day of the massacre, Unsay said he was at the municipal hall, presiding a meeting with local officials from 8 a.m. to 12:30 p.m, having a "normal day" until he was told about the killings.

He added that the prosecution failed to show DNA evidence, fingerprints, photos or videos, and gunshot residues indicating he was present at the massacre site.

He said he and his clan have been "wrongfully accused." Unsay is detained at Camp Bagong Diwa.

Zaldy, for his part, said he was in Manila on November 23 to meet then-president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. He also said he was elsewhere on the days of the alleged planning meetings.

Though under the custody of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology, Zaldy is currently at a hospital in Makati, undergoing therapy after suffering a stroke. He was allowed to attend his daughter's wedding last year.

Sajid, for his part, told the Department of Justice during preliminary investigation that he was at the Commission on Elections' office in another town, filing his wife's certificate of candidacy for mayor, on November 23. He also denied attending the alleged meetings.

Besides, he added, he could not have conspired with his family because he was "harboring ill feeling" against them at the time — in October 2009, his designation as OIC governor was revoked; his father and his brother, Datu Akmad, were installed as governor and vice governor.

Sajid was granted bail in 2015. He paid a surety bond of P11.6 million, or P200,000 for each of 58 counts of murder, in exchange for his temporary release.

Maguindanao Rep. Esmael Mangudadatu offers a prayer at the Ampatuan Massacre marker in front of the National Press Club in Manila on Friday, November 15, 2019, several days before 10th anniversary of the gruesome November 23, 2009 massacre. Over 50 people were killed in the massacre, including 32 journalists and Mangudadatu's wife and sister. Danny Pata

WAITING FOR JUSTICE

Relatives of the massacre victims have been calling for the conviction of the Ampatuans and the other accused for a decade, but they are aware that even a damning judgment would not mean the fight is over.

Convictions are appealable all the way to the Supreme Court, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines' Rowena Paraan said in a program at the massacre site last week.

For now, they wait. Mary Grace Morales, Rosell's widow and a leader of the victims' families, said forgiveness will come when the killers have paid for their crime.

Toto Mangudadatu, for his part, has claimed the kind of violence that killed his wife and sisters will never happen in his province again.

He said he was confident of a conviction, vowing to resign as a congressman in case of an adverse decision. "Buti pa mag-rido na lang du'n," he said, referring to a violent clan feud, but quickly took it back.

"Hindi naman. Kasi as much as possible ayaw namin ng ganu'n," he said last week.

Santos, the private prosecutor, said the political influence of the Ampatuans has waned, but said they might return in the absence of a "strong contender."

"It's up to the people of Maguindanao to choose the right leaders so that the Maguindanao Massacre will never be repeated," she said.

SHARE THIS STORY