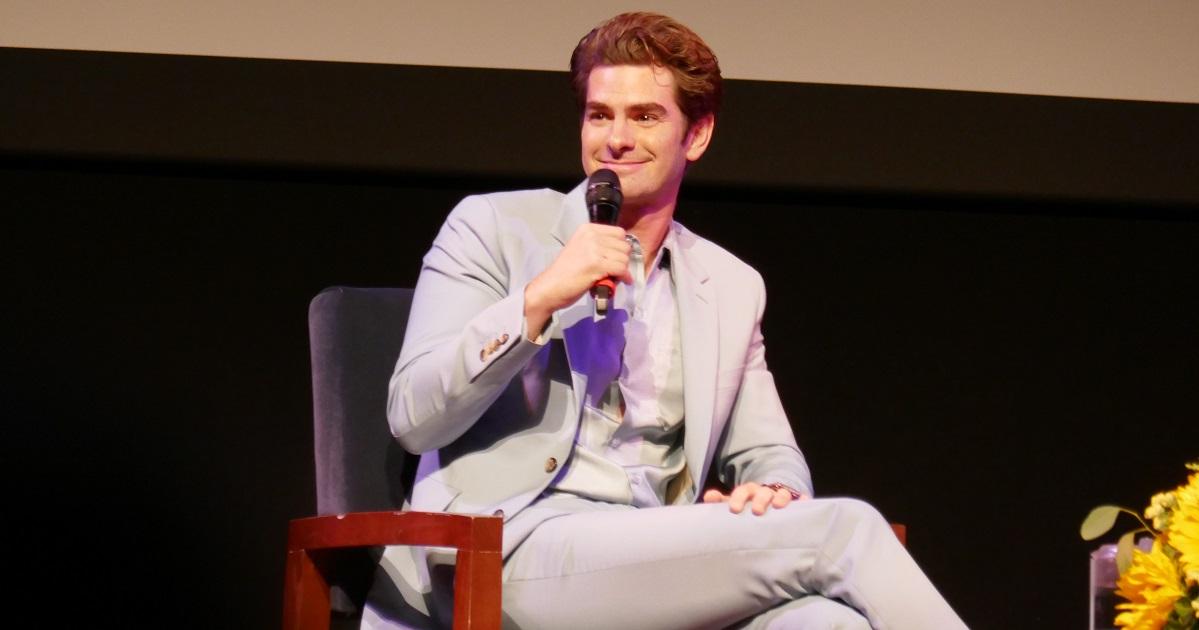

LOS ANGELES — When Film Independent presented "An Evening With … Andrew Garfield" at The Wallis, we didn't expect the talented and amiable 38-year-old British actor to open up on a lot of subjects.

He talked about the death of his mom, Lynn Hillman Garfield, last year from pancreatic cancer, and how he was thinking of her when he was singing the song "Why" of the late Jonathan Larson, the "Rent" lyricist and composer whom he played in Lin Manuel-Miranda's "tick, tick …BOOM!"

The more-than-an-hour-long interview with Dave Karger (host, Turner Classic Movies) as moderator, showed the sensitive, emotional and funny side of the Oscar-nominated actor for his portrayal of Larson.

"Tick, tick … BOOM!" is the story of Larson's life in New York City and the challenges he faced to become a musical theater writer in the 1990s.

Garfield is nominated for Best Actor for the coming Oscars along with Benedict Cumberbatch for "The Power of the Dog," Will Smith for "King Richard," Denzel Washington for "The Tragedy of Macbeth," and Javier Bardem for "Being the Ricardos."

Garfield already won his first Golden Globe Award for Best Performance by an Actor-Comedy or Musical for his role as Larson in "tick, tick…BOOM!" If he wins an Oscar this year, he would be the first leading actor from a musical to win in over 55 years.

Below are excerpts of the conversation with Garfield during that memorable evening.

I bet a lot of people in this room know the answer to this question, which is where you were born. Here, see this sign (Los Angeles)?

Yeah. August 20th, 1983. I think Rod Stewart's son was also born...

Sean.

It might have been Sean. He was either born the same day as my brother or me. Rod Stewart was very mean to my father looking at all the babies in the basinets. My dad was like, "Hey, which one's yours?" Apparently, he was like, "Oh, f*** off." That was interesting. But anyway, that's my little Rod Stewart anecdote.

The fact that you have an American dad and a British mom... is that, in your mind, just an interesting fact, or do you think that actually has been helpful to you in your life as a performer? That you did grow up with different dialects and different inflections?

Yeah, sure, in the technical way of that, but a cultural influence as well. The fact that my dad is a cinephile, and always was, so I was introduced to... when I say cinephile, he loves the great kind of movies of every year and every decade, but he also loves Steven Seagal movies. There's a broad spectrum of culture that I was introduced to.

My mother was obviously a very English working class. She was more into music, poetry, nature, and art. Definitely culturally. But it means I don't support any football team. I don't support any basketball team, but I love the sports. I'm just an appreciator. Weirdly I'm not a beer drinker. I'm lonely when I'm in the UK, because everyone thinks I'm an alien because I don't drink beer and I don't have a team, so I'm just left out of most conversations. Again, it's this split. I feel stretched, in a way, that maybe it's made me more open to all of life.

When you think back to "Lions for Lambs," if people who haven't seen it, it's a compartmentalized movie, which is to say you are basically entirely in a room with Robert Redford, a professor, and a student. What are your recollections of that experience so early on with someone like that? How welcoming was he to you?

He was always late, at least two hours every day. And never ever acknowledged it. Again, I want that confidence to be able to be like, "All right. What are we shooting today? Can I have the sides? Oh, they're in the s***." I'm being unfair. He's the best. I loved it. It was his set. He was the director. It was his set, and he is Robert Redford. It's like, you're the Sundance Kid. Do whatever the hell. I'm just like, "I have to be there." Then it was like doing a play. That's where I started.

I started in the theater. These scenes, it was like a chamber piece between me and him, our third of the film. It's just basically us going back and forth across his desk. He's my college professor. I'm a college student that is not matching up to his potential, and he's trying to wake me up and radicalize me in real time and make me more engaged politically and all these things. It was just a dialogue heavy back and forth. I felt pretty comfortable. I was just really worried about being too theatrical and too big. He just had his eye on it. But after the first take of his, he would always do my coverage first for the most part, generously, just so generously.

Because he knew it was my first movie, and I didn't know what I was doing. He wanted to make me feel really comfortable. Actually, I bring up his lateness because it gave me a more relaxed rhythm. Maybe I'm being too kind, but maybe that was a tactic to go, "Hey, there's no pressure. We can be here all day long. We have time. We got the money. We got the cameras."

Or maybe he was just perpetually late, but either way it allowed me to just be a bit more relaxed and not be so intimidated by the camera. But after the first take of the first time, we did the scene together on his coverage because he turned the camera around for his close up, he finished the tape and he said, "Okay, cut." He looked at me, and he was like, "How was that? What do you think?" I was like, "Really good. It was really good, Robert."

It was very sweet. It was gentle. It felt pressure-less and gentle. That's the hardest thing to create on a set, to create an open, again, and what Lin creates and what Scorsese creates. These great directors, they want you to be relaxed enough to be alive. That's the thing that Fincher does so incredibly as well, is that he spends all his money on time. So that's why he does a thousand takes of me digging up an envelope. Because he wants to make sure that we're just squeezing all of the juice out of the thing that we love to do the most. It's a really, really beautiful thing to leave everything on the field, as it were. After 100 takes, you definitely have done that.

What do you remember as being the process to get that part in "Social Network"?

I remember every moment. I read the script, and it was the greatest film script I think I've ever read. I read it in one sitting. I read it in 45 minutes, and it was 150, 60 pages. It was just like, this is about us. This is about where we're heading. This is about being human. This is somehow so universal and potent and profound. And then I went and read, and then I got recalled. I was reading with Fincher in the room, and then with Aaron in the room. Aaron was reading off-camera lines. I was reading for Mark. I was reading for Mark Zuckerberg for that role and thinking that was what I was reading for. I was. The audition went really, really well, and I could feel it. Aaron can't hide anything. He just stood up and started pacing around the room, trying not to look at me in his sweatpants and weird shoes. He was very excited, and I was a young actor.

I was like, I remembered every single moment of it. I remember Fincher saying under his breath to Aaron, I told you, told you. I was like, "That's great." It was like fist-pumping in my heart. I left thinking I'm going to hear in 20 minutes that I got it, and weeks go by. Then I get a call finally from David saying, "Hey, come to the office." I had a Vespa at that time here in LA. I just zipped. "Yeah. Sure, sure, sure. I'll be there one second." Just counts outside his office. He said, so I have two actors who I think could play Mark. You're one of them. But I only have one that I think could play this other part, Eduardo, and I have to split you up.

I want you to play Eduardo. You could play Mark, but I think it's Jesse (Eisenberg). Jesse can't play at Eduardo. Jesse can really knock the s*** out of Mark. That was it. I was like, "You didn't have to be elaborate about this. I will literally, I will shine your shoes now, and that's enough." So, I was like, "Oh, okay. I guess I'll play this other great part." Then we were just off to the races. We were all so young, and we'd also heard so many horror stories about David and Robert Downey Jr. having to pee into cups on set because he wasn't allowed to go to his trailer.

I don't know if that's real, but it's funny and petulant. I don't know. But as young actors, we were just so obedient. We were just like; we want to do it all. We had the energy. We had the passion. We had the desire, and we allowed ourselves just to be the clay in David's hands. We loved acting. It was like, "Hell yeah. Let's do it again. I'm exhausted. My eyeball's falling out of its socket, and I don't know what I'm saying anymore." But that's what he's looking for. He's looking for the actor to forget that they are acting. He's looking for that moment where they forget where they are, and they're just alive and vulnerable and open. When he feels it, he knows it. I remember walking around behind the set one day, and it was after taking 25 of a really hard, emotional scene. I'm just walking, just trying to stay loose. I hear him saying to his continuity person who does all the... His video guy basically. He's like, "Okay, so delete takes one through 24. Take 25 is the first print." I doubled.

I was like, "There wasn't anything good in one through 24?" There wasn't one moment they could use. Ah. But it was amazing and liberating because you go, "You are David Fincher, and I really do trust you." Yeah, it was funny. He knew I was there. He did it to be like, "This kid is going to..."

It was so fascinating, then, after you had done this group of films, the ones we talked about, also "Never Let You Go," where then we learned that you were taking on "Spiderman." It was such an interesting move on your part, such a successful move on your part, but so different. I am curious to know what, if any, assurances did you ask for and, hopefully, get about what the films were going to be like, what the process was going to be like that made you think, okay, I'm making this leap.

I got no assurances. No, I was a kid, and I had to sign on without having seen a script. That's the way, that's the setup for these larger movies, for people who don't know. It's actually when you screen test, when I screen tested, I had to sign saying, "If you offer it to me, I'm doing it." I was 24. I was impoverished actor. I was doing stuff I love, but Spiderman had been my favorite, my first Halloween costume my mother made for me when I was three out of felt, just so important to me. I did think about it for a few weeks before I said yes to the screen test.

I really did think about it. I was like, "Oh God. There are so many things that could go wrong here. There are so many things that don't feel good for me here." But that rational voice was at war with a raging three-year-old going, "Are you crazy? There's no way we're not doing this. I don't care if it's a piece of s***. We get to put on the costume, and we get to pretend you have an elaborate birthday party for eight months. It's film for all eternity. I don't care." I guess that's how my inner three-year-old speaks.

He's a curmudgeonly, slightly Woody Allen version of myself. "Are you an idiot?" But with less wit. I'm just more direct and not all the awful, creepy stuff. So hard to make a reference about anyone anymore, without qualifying it. Now, I'm tired. So that's going to have a life in an out of context way. Andrew Garfield's three-year-old is Woody Allen. What? All right. And so yeah.

But then you just roll your sleeves up, and you work. I worked as hard as I ever will work on a thing on that. I'm so grateful that I got to do it with some of the greatest actors I'll ever work with, like Emma Stone and Sally Fields. And Martin Sheen is Uncle Ben. You're like, holy Christ. We're going to be okay to a degree, and then it becomes a whole whirlwind of an experience that, as a 25-, 26-year-old, it's affronting because you're about to become very, very famous and very, very well-known. Then you start to realize that your prefrontal cortex hasn't fully formed yet. You're still figuring out who you are. I'm always in perpetual motion trying to figure out who I am.

But now, as a 38-year-old man, I feel able to sit here and take any projections that you are going to put on me, whether it's positive or negative or otherwise. Because I know who I am in a more solid, centered way. Whereas 25-, 26-year-old, I was looking outside still for a lot of my identity. I knew that's why I didn't do social media and all those things. Because as a 25-, 26-year-old, I was like, "I'm wise enough to know that I can't handle this, and it's going to affect me in a way that it's going to create anxiety. It's going to make me start acting to please other people in a way, rather than actually finding my own core, my own path as an artist, and my own path as a person." That's why this interface between public and private is such an important thing for me.

For any young artist that may be in the room as well. I find for me; we have to have the heart of a baby and the skin of a rhino. We have to protect the baby inside. We have to protect that creative child. If we expose it too soon and too often and too vulnerably, that baby is going to start to get banged and bruised in ways that it will distort. We all want to be Lin-Manuel Miranda in that regard. We all want to protect that in a creative child. Not make the things that he makes. We want you to make our own things. But for me, how do we preserve the ability to express freely and express uniquely that unique giftedness that each of us has. I knew. I was like, "I have to really manage that."

I'm sure this last six months have been overwhelming to you, just because you had "The Eyes of Tammy Faye" and "Spider-Man: No Way Home" and "tick, tick...BOOM!" which were all filmed at different times, but they all came out around the same time. I'm sure you were like, oh my God, make it stop. I want to move into a conversation about "tick, tick...BOOM!" In your performance of "Why," how do you summon that emotion for as many takes and as many angles and as many shots as it required?

So, God, so I cried watching that, not because of what I'm doing, but because it's... Oh, f***. I'm singing for my mother in it, and I'm just so grateful that I got to do that, and I got to share that with people who watch the film. It's a bit much, because that's the loss. That's loss. That's the biggest loss I've ever experienced in my life and trying to deal with it and trying to understand how to move through it and move on with it.

The kind of process that Jonathan is going through in that scene is that process, is how do I meet this loss of my friend? How do I meet this loss of my best friend and so many people around me and how do I go on doing the thing that I think I'm supposed to do which is write music? Is that enough? Is that enough? It's short and it's sacred, this life and we're here and then we're not. How do we know what we're supposed to be doing? Am I cut out for it? What's the way I want to spend my time?

In that moment, Jonathan gets the message from Robin's character Michael, and I love that Lin and the editors put that cut of grown-up Robin, grown up Michael, and grown-up John in the workshop with Michael responding to... the Superbia workshop and then looking at his friend and then John receiving that look and going, "Okay, I'm going to keep doing it because it's not just for me. It's for my community. It's for you. It's for you that I love."

That is the connective piece in that song that Jonathan gets to where he's like, "I can justify doing it if it means that I'm advocating for something bigger than just me. That I'm advocating for life. That I'm advocating for dignity," and sorry, "I'm advocating for the sacredness of all of us and especially people who are not treated as sacred by the world and by the culture." That's who Jonathan was surrounded by. So, for me, it was a message in a bottle from my mom, for my mom, for Jonathan, for Jonathan's community, a lot of who were lost during the AIDS epidemic. It was this container of grief and of longing for more life as Prior Walter would say in Angels in America. It was Prior Walter. It was for Tony Kushner. So, accessing that was... I still have it here. It's here. It's alive in me, and it's what makes life worth living.

The awareness that we're only here for a moment and that we're going to lose everyone that we love means that we better be here fully, and that is where Johnathan realizes... That's where he gets to in that song, so we got it on the second take of the close up. Like it was fine after the second take. The second take. Just to be technical for a second, so I don't keep crying, I asked Lin and Alice, our amazing cinematographer, Mike Fuchs, our great camera operator, to start tight on me, whatever that mastered tight performance shot would be, because I know that crazy stuff happens in the first few takes is magic.

The first take is usually magic, and then the second take is usually magic. I knew I wanted to sing it live as well. I knew I wanted to make sure that we got it live, because it was going to be broken and it was going to be raw, and it was going to be rough, and it was going to be found. It's a spontaneous song, it's not written, he's just making it up as he... I had to feel like... I had to sing it live, and that was week one of shooting and I hated Lin so much. I saw it on the schedule, and I was like, "What's this?" He was like, "Buddy, it's great. You're going to get it under your belt. And then you're going to end this. Then the rest is going to be a cakewalk." And I was like, "No, no, no, no, no, m***********. What is this?" I was like, "What's the real reason? Don't b******* a b**********." He paused, and he looked me in the eye, and he was like, "Okay, I think I'm now understanding who Andrew is. I can't just placate." He's like, "Well, we're going to lose location unless we shoot it in the first week." So, I was like, "Thank you. F*** you. I have to go. I have to go prepare."

Anyway, but the two things were true. We were going to lose the location, but also the first reason was also true in the sense that it did feel like this mountain and Julie Larson was there that night, John's sister, our producer, and there was a kind of a... Whenever Julie was with us, there was... F***, I don't want to cry again, man. But there was another spiritual dimension that was added to the set. Even when she wasn't with us, we summoned her. We called her in kind of thing. So, yeah, take two. I came to after the take in that great way that you rarely get as an actor where you wake up out of a scene or a moment, you go, "Oh, I think something just happened." I wasn't aware of it. I was very, very locked in and Lin came out and he was like... Whatever. That was obviously a good sign. Alice was like, "I mean, that's it." Like the sound mixer was like... Tod was like, "We got it." I'm like, "When does a sound mixer do like..." Like I'm done. That's it. It was cool.

It was one of those great moments on set and I usually would be hesitant to say, "Oh yeah, we nailed it," but actually, it transcended nailing a scene. It was like, "I got to commune with my mom. I got to commune with John," and they filmed it and I forgot they were filming it, and I got to just offer her to the world in a way. Offer where she lives in my heart in that scene, and then the rest was a lot easier. It's beautiful to have that opportunity.

You just met Lynn Garfield a little bit. You just met my mom Lynn Hillman Garfield. It's really touching because I wish she was here. I wish she could be here, but now you all get a bit more of a sense of who she was and her spirit, and that's beautiful too.

I'm not aware of the exact chronology of her passing compared to when you met with Lin and decided to do this film. So, I'm curious to know from you, was part of the appeal of this the idea of maybe being able to process through her loss or did this all become apparent after the fact, in the making of the movie that this could be helpful for you to remember her.

It just happened. She didn't pass until just before we started shooting and yeah... While I was shooting "The Eyes of Tammy Faye," they were very gracious. Jessica (Chastain) and everyone on that set. I said to them before we started shooting, because my mom has been sick for a year with pancreatic cancer. It was really rough. It was really rough for her, and I remember saying to them before I signed on, I was like, "If I get the call to go home, I'm going home, and I don't care what it costs production."

Little did I know, I didn't need to say that because they're incredible human beings on that production. When I got the call from my dad and my brother and my mom. Oh, sorry. Damn it. They said, "Don't hesitate. Book a flight." They shut down production for 10 days and two weeks, and I got to be with my mom for the last 10 days of her life, and it was the greatest time. The best time, the best 10 days of my life, and the privilege of being with her as she passed and then finished Tammy Faye and then started tick, tick… BOOM! early 2020. Then the pandemic. Then I had lots of time to myself alone and I got to really do the proper grieving with her, and it was a beautiful, strange thing that happened in that solitude that I got to really just dig in and really be with her as she passed.

Now that this experience is over, what is the one line lyrically from "tick, tick... BOOM!" that jumps into your head the most often?

What a way to spend the day. That's the essence. What a way to spend the day. Because what a way to spend the day and what a way to spend the evening.

—MGP, GMA News