Al Pacino, Robert De Niro and Martin Scorsese on making ‘The Irishman’

Los Angeles — It is very rare that three legends and icons — Al Pacino, 79, Robert De Niro, 76, and Martin Scorsese, 76 — make a film all together. And yet here we are.

"The Irishman" is an epic crime film directed and produced by Scorsese and De Niro, who have already worked in nine feature films prior. Pacino and De Niro have worked in two, while Pacino and Scorsese have never worked together.

Until "The Irishman" that is. It also happens to be the first time all three of them came together for a project.

"The Irishman" is based on the 2004 book, “I Heard You Paint Houses” by Charles Brandt, about Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran (Robert De Niro), a truck driver who becomes a hitman and gets involved with the mobsters and the powerful Teamster Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino).

The film runs at 3 ½ hours long. It is the longest film Scorsese has directed and the longest mainstream film released in over 20 years. It also took almost a decade to make and 106 days long to film. Shot in New York City and sections of Long Island, it is the most expensive film of Scorsese with a production budget of $159 million.

Below are excerpts of our conversations with the three legends as they talk of the challenges of making the movie, how they started in their lives as actors, their friendships and the moment they decided to dedicate their lives to their passions whether it be acting or filmmaking.

Al Pacino

We have little bits of information of who we think Jimmy Hoffa is. Stepping into those shoes, what did you know about him before this and did you gain any empathy or new insights into him having gone through this experience?

You look into people when you’re acting them, when you’re going to portray them. There’s a lot of footage on him, which helped me. I found out the key things about someone because you’re reading or something. It’s always revisionist but you try to put together something that connects to the script also. You’re portraying a character from the text.

I learned a lot of things, I learned a lot about that period where he started when he was a teenager and he was with the unions and what was going on with the workers and child labor and everything. So they gave me a little history.

Then I watched him, when I was interpreting him, his age. I marveled at a couple of things. One, that he was probably the most popular person second to the President of the United States at the time. He was really an icon because he was coming from a place of real passion and a need to help the worker. I hope some of that comes out in the role, which is you can see, he would defy anyone.

But at the same time when he was thrown in prison for five years, he saw what was going on there with the prisoners and he went all out to help them and to find a way because the treatment was awful.

Back in the day, there wasn't an American alive who didn't know who Jimmy Hoffa was.

A post shared by The Irishman (@theirishmanfilm) on

He galvanized these people. He had that ability because he had the passion for it and the need and he believed in it. So he was a visionary in that sense. That was very interesting to me that he would be someone who associated with certain kinds of people, that’s what we did think of him.

When I was a kid, Jimmy Hoffa was always in the papers. He was always on people’s lists of pros and cons; he was a controversial kind of guy. And because somehow leanings of a certain negative group, considered negative and all that — so you got a sense of someone who was associated with different kinds of factions. That was union stuff. I don’t think it’s there anymore but I do think at that time it was really prevalent. I marveled at the fact, this is a man who would be fighting John F. Kennedy Jr., a hero to liberal, for the people and at real odds with him yet be an advocate for Dr. Martin Luther King. So to me, this was an interesting person. That said, it is all about Jimmy Hoffa for me.

The names Al Pacino and Robert De Niro have been mentioned in the same sentence over the years to define a generation of actors. Can you talk about your relationship? He told us there are things that he can discuss with you but can’t discuss with other people because you are in a similar situation.

Really? (Laughs) No, I’m joking. Of course, I met him when he was a young man; we were in our mid-20’s. I met him on 14th Street — I was living on 14th Street between Avenue B and C at the time with my wonderful girlfriend, who was Jill Clayburgh, who’s passed on.

So we were very close, we were together many years and she knew Robert from Sarah Lawrence and they worked together in films with Brian de Palma. I met him on the street, and I was introduced to him. I’ll never forget it. I thought when I met him that he was an interesting guy.

I even said to her, who is this guy? Interesting guy. He exuded a sort of thing, I didn’t even understand it but I felt it. She said, oh he’s a great actor, I worked with him. Then I remember him. Something happened in the course of our lives that brought us together but probably was because we happened at the same time, unknown until I guess ’69, ’70, something like that.

Then our careers started paralleling and we were compared to each other, etc. There was a lot of stuff about all that. We would meet from time to time in the course of it. Probably it was a little different back then when you became famous, it was not something that was talked about much or readily accessible. We were caught off guard so to speak, that what happens to you when you get in that position. There’s a period of adjustment.

Bob and I would occasionally meet and we would talk about it, about what was happening to us. That gave us a bond that we’ve kept throughout. I feel toward Bob like a brother and I trust him. I have Bob to thank for getting this part. This was his idea. This whole project was. He got Marty and got me with Marty, who I had never worked with before. So that’s the kind of thing we have and the kind of person he is.

What was the moment you fell in love with acting? When did you realize yes I can actually make a living out of this?

When I was a kid, I was just a kid…I don’t know that I fell in love with it but I realized I could do it. It was a way of getting attention and getting out of certain classes at school because I didn’t like school.

So I would be in the plays, school plays and I would be doing this and I thought, I’ll be an actor because it sounded viable. I wondered, what is this thing that I do that they seem to respond to?

Robert de Niro

The movie takes some leaps of faith in regard to the Kennedy assassination and what happened to Jimmy Hoffa. How do you like playing with history like that in a movie?

When I read the book, I believe all the texture, all the things that cumulatively added up to the grand finale of the book and the final say of the book made sense to me.

I believed it, those things I know are real. So if all those things are so real and so convincing, and such a simple result of say with the Gallo situation and with Hoffa, to me, it’s okay to present that, because it’s also fiction in the sense that it’s part of the vision of the film. So it doesn’t have to be accurate.

When you make wild accusations, I’m not that way, crazy like some other movies that they do go off here and there. I’m not too, because it’s too obvious. This, to me, is very plausible.

You have known Al Pacino since you guys were very young but you didn’t have many chances of working together. And you were the one who was working with Martin Scorsese for many times and this is the first time for Al. Can you talk a little bit about the dynamics of working together?

Al and I have known each other since we were in our 20s and we get together from time to time over the years and talk about stuff, especially as our situations changed and we felt we could talk stuff that is hard to talk with a lot of people other than people who have been in the same situation. So that was a good thing for both of us.

As far as the movie “The Irishman” goes, it took a long time to get it to this point. Al and I were once at a premiere of a film about 12, 13, 14 years ago and the people were so nice and it was such a great thing. It was either London or Paris or Spain — the people were so nice! We said, we agreed that we would like to one day — someone said I’d like to be here and really do something for the fans that we really are proud of, and so maybe one day that will hopefully happen.

I don’t know if I was even aware of “The Irishman” at the time or “I Heard You Paint Houses.” And so later I said to him, his last day of shooting, that’s two years ago, well remember that time we spoke about this? Hopefully we are happy, this is one we had a good time doing, and it’s the right one for us.

What was the moment you fell in love with acting? When did you realize yes I can actually make a living out of this?

So I was doing this play and this guy came up to me afterwards and I must have been 12 or 13, he came up to me, he says hey man, you’re the next Marlon Brando. I looked at him I said, who’s Marlon Brando?

So I went to Performing Arts, which was funded. At the same time I was doing things and I remember I loved the things you learned but you’re too young. I was too young. I was 15. I might as well have been 10 or 11, I just was behind. Where I come from, the life I lived and all that stuff, you don’t want to know about that. But it was an interesting life at the same time.

I didn’t know about this acting thing and I was in Performing Arts and again, I didn’t have to do much academic work. I loved English but the rest…I remember going into the Spanish class there and the teacher was speaking in Spanish to the students, who already had two years of Spanish and I was supposed to be speaking Spanish with them.

I didn’t know what she was talking about, I’m really finished. So I started helping the nurse at the school. These are funny stories, they really are, interesting. But I got out of there, got out of school, I had to go to work, I had to quit school to go to work, my mother was ill. So I was living in the Village myself when I was 16. I had a room there, around there.

I was sending money, working odd jobs, to support myself, my mother, for a couple of years. But down there, I went to the Berghof Studio then I met Charlie Love, my dearest beloved friend who has passed on. Charlie Love, who was my mentor, he was older. I just saw him one time and I thought this is someone I want to — and Charlie introduced me to a whole world, especially literature and that’s when my reading started. I was doing a lot of things; I didn’t know that I was going to do anything spectacular in terms of a change in my life.

I was a city messenger. I was a bicycle messenger, that’s how I learned Manhattan —11 hours a day riding a bicycle — I looked pretty good. So I went and met the guy who was the dispatcher there, a few years later, his name was Frank Biancamano. He was a dispatcher. I walked in to audition. I had this show business paper. I looked. They showed you plays that are auditioning. I auditioned for him. Anyway, it was this thing called the Actor’s Gallery and it was a whole different kind of thing and I was in there working and at the time I had no home.

My mother had died and I was alone and I didn’t have a house. I was homeless actually. So I used to sleep on the stage at the theater that I played on at night, which is fun. Because I’d find somewhere, a little bottle of beer or something, be out there…I remember being with Charlie and I had a group of people that I stayed with, they were actors and artists etc. Suddenly, I wondered where I was going with this but I knew it was something I was headed for. Then I did this play called “The Creditors” by August Strindberg and something happened to me. That was it.

It’s a long story, but that was it, the moment when I realized that this work is going to save my life, and it did. I found that this is what I wanted to do, whatever else happened, whatever it was, I didn’t think about it. I only thought about being able to engage in this kind of stuff.

In this movie, you performed the older character and the younger version of your character. Did you use different techniques? What did you discover about this younger version of you?

It was interesting. The idea when we first started trying to get the project going, there was talk about younger actors who were for me and Al and Joe (Pesci). But then as time went on and we got older, technology improved in this area.

Marty, at one point, decided — and with Netflix coming on — Marty decided to go with this, and the idea was by Pablo Helman at ILM was to make it the very best that it could be. That was exciting to us that actually we could be in all the film, the whole film, but younger and so on. So, we did tests, and we arrived at what we did. But the excitement was about actually doing something that might be as good as it can be, and people would like and appreciate and get and say yeah it works.

But was the acting the same?

Sometimes when Al or I or Joe would have to do something, we had a movement coach, I forget his title, Gary Tacon would tap us on the back if we were too slouched or something or not spry enough to, like going down the stairs, there was a thing where I go down the stairs to meet Ray Romano in a scene, and I went down the stairs and looking back and he pointed it out to me, I was stepping a little more carefully. He said, you know you are a young guy; you are 39, you jump down like this. So he said you have to let yourself go down the stairs. I said, oh yeah, I remember that’s how I used to do it. So, I did. I let myself go down, bounced down the stairs. I did it, and it was okay. Then Marty cut it out.

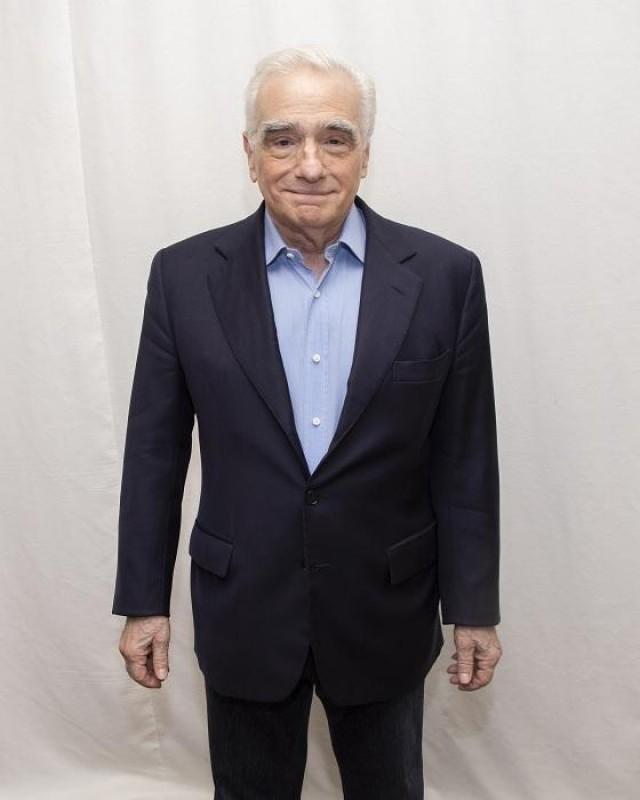

Martin Scorsese

Watching this film, I noticed that there is a difference between this and your previous films about mobsters – “Goodfellas” or “Casino.” There’s no glamour. They are just regular people, very dark, very gritty. Why did you go in that direction?

That’s a good question, because having gone to the other place, specifically “Casino,” which was an extravaganza, this, there’s no place else to go but to get to the real power.

And the real power is quiet and dark, the dark forces of history. You never see who it is. We don’t know who assassinated JFK. We don’t know who assassinated Bobby. We don’t know who assassinated Martin Luther King and if we did, would it make any difference now? We don’t know, and it’s out of our hands in a way and we see how these things are done.

Over the years, when I was growing up, I saw people in conversation so to speak. I saw the body language and I knew that something heavy was happening. I am not talking about Presidents. I’m talking about on a street corner or a little bar somewhere, as a child or as a young person, you know not to go near, just show respect and move away. (laughs)

But I saw it happen and I saw the fear that it could provoke among people like my parents who were garment workers, and still had to live under that way in our neighborhood.

And so, for me, let’s get right down to the heart of it, and the heart of it was two or three people sitting in a bar or a restaurant or a car. They don’t even have to say what they are going to do, it’s a look.

Ultimately, I thought it was a really remarkable story. I think someone pointed out and said a few weeks ago, not that we know for certain that Jimmy Hoffa got killed this way, but the person said, now I know what happened to Jimmy Hoffa. Because of the dialogue scenes, the arguments and he’s right, it’s his union. But he got in with the wrong people. He underestimated.

When someone gets an obstruction in that way, they get taken out, very simply taken out, no one knows you see.

And so, I thought that’s something, because that’s not just mob, which again is human endeavor. That’s like power and usurpation of power and sometimes like Julius Caesar, who put himself in a situation, he had to be taken out, by his adopted son Brutus. Was Brutus really for the Republic, when the Republic was falling apart or was, he in it partially for himself?

But Caesar was going to be a dictator, there’s no doubt. Was he a great man? Yes. But he went too far, taken out. So, this is something which has to do with pride and power. So that is why it’s an essential way, and the framing came that way in the movie. It got tighter and tighter and I didn’t move that much, I didn’t need to.

We have been discussing what cinema is and should be because of something you said about superhero movies. Can you discuss about what we want out of the art form that is film?

Well I think so. We go back to cinema; film was created here in this country and France also at the same time. But the art of cinema, the editing, the art of cinema, came from here and created this wonderful extraordinary art form.

It’s been over 100 years, the world has changed, communication has changed, and the art form is changing. What I’m concerned about was about the possibility of the opportunity to show cinema, films, movies, whatever you want to call them and commercial films, it’s not a bad term, commercial is art, but a product may be different you see. So, where is the room now for a film that’s about people in the theaters, where is the room?

For me, from what I have been knowing and seeing over the past few years, the superhero films are pictures that are proliferating and also in a sense invading the cinema experience. However, that doesn’t mean they are bad films.

I am saying, in my view, when we were young, we loved to go to an amusement park, and the family would go and everything, well now in the amusement park, you would have a film and that’s part of the amusement, that’s part of the experience. That for me, when I say amusement park, films or theme park films, that’s what these are, I feel.

It’s a new form, but it shouldn’t cast us out or me, not me, I’m old now, it’s over, but I’m talking about the younger people. They shouldn’t cast us out.

You should go look — we had “Singing in the Rain,” and we have “Moonlight,” that’s cinema. You want superheroes, go ahead, fine, go to whatever theme park there is, now you could have the amusement park right there because it’s a theater. That becomes the theme ride in a sense, the theme park ride. But don’t confuse that.

When people say oh this superhero film was the greatest opening night in movie history, it made cinema history, no it didn’t. It made box office history. Which is great! Look, you make a theater, you want people to come in and see the movies, they need the money in the theaters, and I understand that.

But it made box office history and it’s a different thing and then it becomes about who makes more money every two months.

So, what about the art? Now when you say what about the art? You say, oh he’s an old man, but what about our children, what are we teaching the children? Hitchcock’s films were crowd-pleasers. And people, when I would go, especially in the '50s and I even saw “Psycho” on the third night, midnight showing at DeMille Theater in New York, it was wild.

So, we would all go, and it would be an incredible, almost theme park-like experience, but what’s the difference between the Hitchcock films and the superhero films? The Hitchcock films ten years later, you learn a little more. Twenty years later, you are still connected. Why? Because it’s about humanity, it’s about our failures, it’s about our moral conflicts and dilemma. It isn’t about a good guy coming in and beating up the bad guy. Now that can be done very well, you follow.

I’m not saying they are bad; I’m just saying that can be done very well. But to enrich the human experience for our young people, they have to learn a respect for this kind of film, for the film that we tried to make over the years and we hope to continue to make. We are being marginalized by the theaters. We’re being kicked out by the theaters. — LA, GMA News