Philippines emits the most number of riverine plastic into the ocean, study finds

Here's a recognition we don't really want to be associated with.

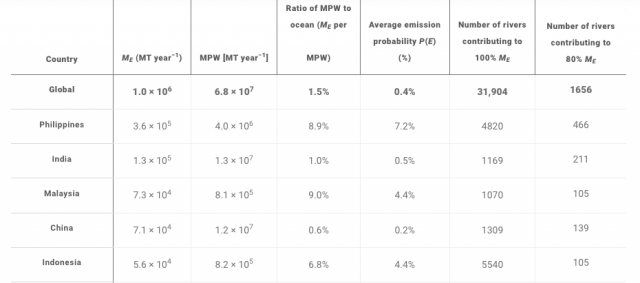

A study published in 2021 in the journal Science Advances showed the Philippines topping the list of countries that emit the most number of riverine plastic into the ocean.

Led by Dutch researcher Lourens Meijer, the study said more than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions and Philippine rivers have mostly contributed to it.

"The largest contributing country estimated by our model was the Philippines," it said.

India ranked second, Malaysia third; and China and Indonesia at 4th and 5th place respectively.

In a recent virtual symposium on microplastics organized by REY Laboratories of Mindanao State University at Naawan, in partnership with Oceana, Caraga State University, and the National Research Council of the Philippines DOST-NRCP, Dr. Hernando Bacosa, PhD. of the Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology delved deeper into the riverine pollution study and pointed out that "the 466 rivers in the Philippines contribute three times the amount of plastics into the ocean compared to India."

He also highlighted another key finding of the study: The Pasig River is the most polluting river in the world (though the study noted it used a model that overestimated the plastic emissions of the Pasig River and that measurements were taken at the end of an unusually dry season of 2019).

Speaking to GMA News Online, Bacosa said the Pasig River alone accounts for 6.4% of the 80% riverine plastic pollution.

"That's something like 2 kilos per second of plastic waste emitted to the sea," he estimates.

His students sought to corroborate and verify the findings of Meijer. Judea Requiron looked at the Pulauan River in Zamboanga, Rojin Mondero and Carl Kenneth Navarro at the Agusan River; Arlene Escanan of the Espanola area of Palawan, and Aiza Gabriel of the Cagayan de Oro River, and the all found the same thing: There is so much plastic found in rivers across the Philippines.

"It's really alarming," Bacosa said, citing the fact that we are a tiny archipelagic country dependent on marine resources that are vital to the livelihood of a lot of Filipinos.

"The Philippines is experiencing historical levels of plastic pollution, especially in marine environment," he emphasized.

It's not a surprise. In 2018, a UN report found the Philippines to be among the Top 5 countries producing half of the world's plastic waste.

And according to a 2019 Global Alliance for Incinerators Alternatives report, the Philippines produces some 164M sachets, 45.2M labo bags and 48M shopping bags daily.

We all know where these plastics end up.

Only 9% of plastics used across the world is recycled, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development reported earlier this year.

Meanwhile, Meijer's study estimates about 60% "of all the plastics ever made to date" have been discarded in landfills or in the natural environment.

These "land-based plastics are among the main sources of marine plastic pollution, either by direct emission from coastal zones or by transport through rivers," it said.

The presence of plastic in the marine environment doesn't just endanger aquatic life, as evidenced by a growing number of marine life dying from ingested plastic, it is also very costly to clean up and poses damage to vessels as well as to gears used in fisheries.

But here's another important thing that Oceana's vice president Atty. Gloria Estenzo Ramos said at the symposium: "The plastic crisis is also a climate crisis."

According to the Center for International Environmental Law, "about 99% of plastic is made from chemicals sourced fossil fuels," which as we all know, emit greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change and global warming.

The very presence of plastic confirms a substantial contribution to climate change and global warming.

"In all stages of its life cycle, plastic has a huge detrimental effect on climate change," Ramos continued, as she urged to cut back on plastics and find solutions.

There are the occasional coastal cleanups and a peppering of consumer-led changes such as going from plastic bags to reusable ones, the popular shift to tumblers and water bottles in place of disposable coffee cups and bottled water, as well as the rising acceptance of the refilling model.

There are also nature-based solutions we can turn to, like planting mangroves, which can effectively filter and prevent plastics from entering the ocean — among other amazing things mangroves can do.

And let's not forget the importance of community-led initiatives like the River Warriors of the Pasig River, who already have successful clean-up efforts to their name.

Most importantly perhaps is government action in terms of legislation and implementation. On top of The Philippines' strong solid waste management law that aims to protect the environment through proper solid waste management practices, local government units can also take a more active approach in managing plastics waste and usage.

For instance, Quezon City in 2019 has already banned single-use plastics and disposable materials from hotels, restaurants, and other establishments.

While plenty environmentalists decry it for not being enough, the Extended Producers' Responsbility bill — which makes it the responsibility of companies to properly recover, recycle, treat, or dispose what they produce post-sale and consumption — has already lapsed into law last July.

Meanwhile, Senator Loren Legarda has also filed a bill that aims to regulate the manufacturing, importation, as well as use of single-use products.

At the symposium, Dr. Riley Howard of elaw.org said it most straightforwardly: "It's now important to think about how we can stop creating new plastics."

"We need to focus on turning off input of new plastics," she emphasized.

And if we may add — sooner rather than later. Microplastics have already been found in salt and most recently, in human blood. — LA, GMA News