Study casts doubt on reliability of rapid antigen tests in kids; COVID-19 transmission through breastmilk unlikely

The following is a summary of some recent studies on COVID-19. They include research that warrants further study to corroborate the findings and that has yet to be certified by peer review.

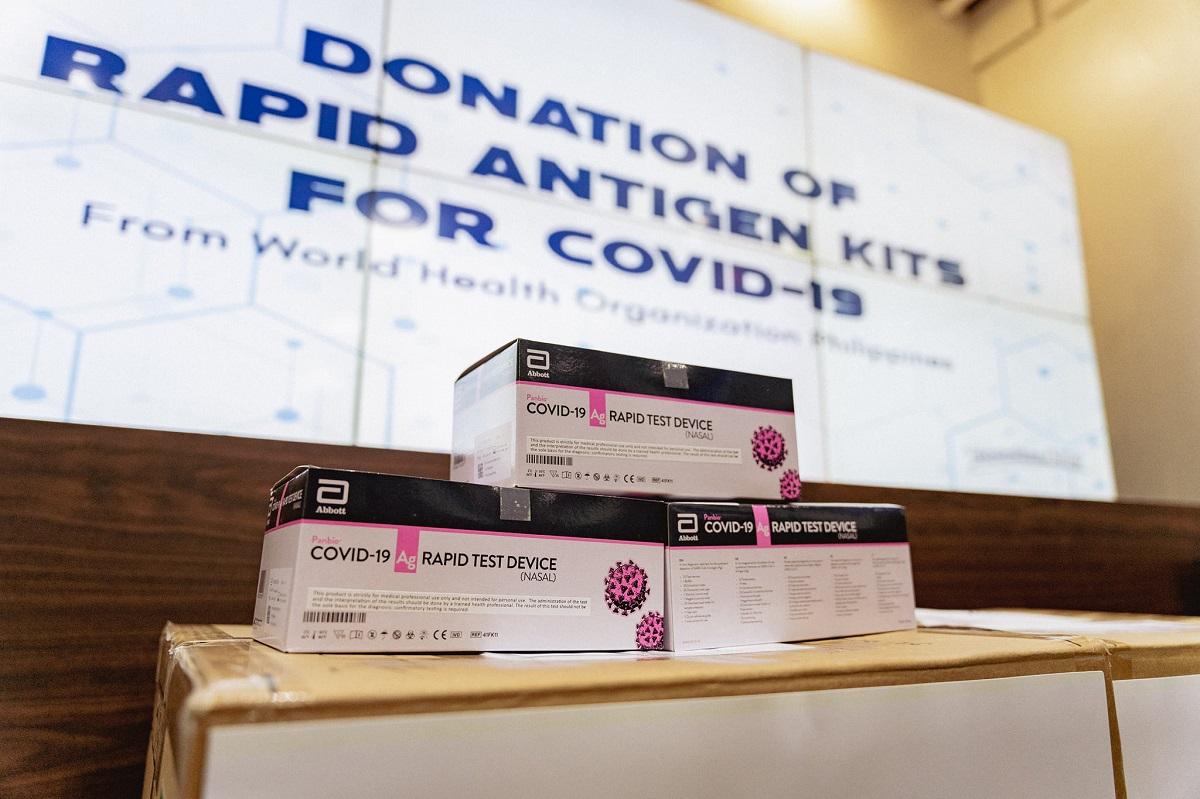

Rapid antigen tests may be unreliable in children

When used in children, rapid antigen tests for detecting the coronavirus do not meet accuracy criteria set by the World Health Organization and US and UK device regulators, according to researchers who reviewed 17 studies of the tests.

The trials evaluated six brands of tests in more than 6,300 children and teenagers through May 2021. In all but one study, the tests were administered by trained workers.

Overall, compared to PCR tests, the antigen tests failed to detect the virus in 36% of infected children, the researchers reported on Tuesday in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

Among children with symptoms, it missed 28% of infections. Among infected kids without symptoms, the tests missed the virus in 44%. Only about 1% of the time did the tests mistakenly diagnose the virus in a child who was not actually infected.

Given that more than 500 antigen tests are available in Europe alone, the authors said, "the performance of most antigen tests under real-life conditions remains unknown." But the new findings "cast doubt on the effectiveness" of rapid antigen tests for widespread testing in schools, they concluded.

Breastmilk transmission of COVID-19 unlikely

A new study appears to confirm smaller, earlier studies that suggested nursing mothers are unlikely to transmit the coronavirus in breastmilk.

Between March and September 2020, researchers obtained multiple breastmilk samples from 110 lactating women, including 65 with positive COVID-19 tests, 36 with symptoms who had not been tested, and a control group of 9 women with negative COVID-19 tests.

Seven women (6%) - six with positive tests and one who had not been tested - had non-infectious genetic material (RNA) from the virus in their breastmilk, but none of the samples had any evidence of active virus, according to a report published on Wednesday in Pediatric Research.

Why breastmilk would contain coronavirus RNA but not infectious virus is unclear, said study leader Dr. Paul Krogstad of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, "Breastmilk is known to contain protective factors against infection, including antibodies that reflect both the mother's exposure to viruses and other infectious agents and to vaccines she has received," he noted.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises that before breastfeeding, bottle-feeding, or expressing milk, women with COVID-19 should wash their hands or use hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol. The CDC also recommends that they wear a mask when within 6 feet (1.8 meters) of the baby.

New technique may speed vaccine, antibody drug development

Researchers are working on a way to speed development of vaccines and monoclonal antibody drugs for COVID-19 and other illnesses, shortening the time from collection of volunteers' blood samples to identification of potentially useful antibodies from months to weeks.

As described in Science Advances on Wednesday, the new technique employs cryo-electron microscopy, or cryoEM, which involves freezing the biological sample to view it with the least possible distortion.

Currently, "generation of monoclonal antibodies involves several steps, is expensive, and typically takes somewhere on the order of two to three months, and at the end of that process you still need to perform structural analysis of the antibodies" to figure out where they attach themselves to their target, and how they actually work, explained Andrew Ward of Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

In experiments using the new approach to look for antibodies to HIV, "we flipped the process on its head... by starting with structure," Ward said.

Because cryoEM affords such high resolution, instead of having to laboriously sort through antibody-producing immune cells one by one to identify promising antibodies, the process of identifying antibodies, mapping their structure and seeing how they are likely to attack viruses and other targets goes much faster, he added. "The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for such robust and rapid technologies," his team concluded. -- Reuters