This tiny fish drugs predators to escape certain death

Tiny tropical fish called a fang blenny has a unique tactic it employs to avoid getting eaten alive: it uses its fangs to inject predators with “drugs” that cause weakness and dizziness.

The fang blennies’ small size makes them a usual target of bigger fish, which usually devour them whole. But should a fang blenny find itself inside the predator’s mouth, it sinks its mighty lower canines into the creature. This releases venom into the predator, causing its jaw to slacken. This then allows the fang blenny to make a hasty escape.

This behavior was actually observed by zoologist George Losey over 40 years ago, who even went so far as to test the venom on himself.

“The toxicity of the bite of Meiacanthus atrodorsalis was assayed by force-biting the tails of two white laboratory mice and my hand,” Losey stated in his 1972 research paper. “Subsequent observations were inadvertently provided by bites in the more tender area of my hip.”

Despite continued research on the fang blenny’s venom, its chemical composition remained a secret to scientists… until now.

Led by Nicholas Casewell, an international research team has determined what compounds make up the fang blenny’s venom.

There are many types of fang blenny, but the Meiacanthus is the only one whose canines come with venom glands. The biologists discovered that these glands produce three toxins – all of which can’t be found in any other fish. The first group of toxins, phospholipases, is commonly found in the venom of scorpions, bees, and snakes. The second type, neuropeptide Y, is found in the cone snail, which uses the toxin to cause its victims’ blood pressure to drop to lethally low levels.

The third group consists of opioid hormones known as enkephalins, which are like the natural endorphins released during laughter or exercise that result in feel-good effects. Enkephalins also work on the same molecules targeted by synthesized opioid painkillers such as oxycodone or fentanyl.

“Its venom is chemically unique,” said co-lead researcher Brian Fry from Australia’s University of Queensland. “The fish injects other fish with opioid peptides that act like heroin or morphine, inhibiting pain rather than causing it.”

According to the team’s Irina Vetter, however, the fang blenny venom doesn’t exactly act like a painkiller.

“These substances have to be released in the brain to have that type of activity,” she said. “It’s unlikely that they would relieve pain when we’re bitten by a fish because they can’t get into the brain that way.”

The researchers think the venom instead causes the predator’s blood pressure to crash, leaving them dizzy, uncoordinated, and weak, which in turn loosens their mouths open, allowing the fang blenny to swim outwards to safety.

Truly special

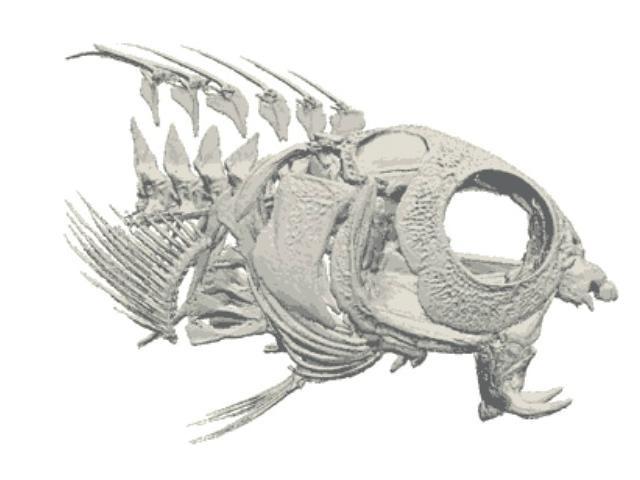

The seas are home to around 2,500 fish species with venom that cause severe pain that can last for days. All of them, however, use the spines on their backs, tails, or fins to inject the venom into their victims. Examples of such fish include stingrays, stonefish, and lionfish.

This makes the fang blenny truly special. Not only does its venom not cause pain, it is also one of only two species of fish (the other is a poorly understood deep-sea eel) that delivers venom into its prey through bites.

The biologists also discovered that a non-venomous variant of the fang blenny, called the Plagiotremus, mimics the color and swimming patterns of its venomous counterpart to discourage predators from eating it.

The field of venom research has been of great benefit to medicine, allowing scientists to identify new compounds that can potentially be used to develop new, more potent drugs. In fact, venomous spiders, snakes, scorpions, and fish have yielded all sorts of useful chemicals for use in the treatment of various conditions and maladies.

“This is a monumental amount of work and it’s remarkable that the team pulled it all together,” said the University of Kansas’ Leo Smith. “My main hope with this exciting study is that it will encourage researchers to explore the other 2,500 venomous fishes.”

For the published research paper, head on to Current Biology. — TJD, GMA News