High school kids make healthier pandesal from pili nut flour

Few foods are as familiar to the Filipino palette as the pili nut. Known for its sweet taste and crunch, this unique delicacy is a staple of pasalubong stalls everywhere, gaining the attention of locals and foreigners alike.

Raw pili nuts contain lots of protein, dietary fiber, calcium, phosphorus and potassium. They are also touted for their antioxidant properties.

Inspired by the widespread popularity of this humble nut, a group of teens from the Immaculate Conception Academy (ICA) in Greenhills, San Juan, Manila, were able to make their own pili nut flour in their school’s laboratory.

When made into bread, the pili nut flour was found to be a healthier alternative to the classic pandesal. The students dubbed their product the pili nut pandesal, which was accepted as an entry to the 2013 DOST Regional Invention Competition and Exhibits (DOST-RICE).

Jody Uy, Michelle Tangco, Kim Hsieh, Samantha Hao and Marice Lim are college juniors right now. But back in their junior year of high school, they wrote a paper entitled, “A Study on Prolonging the Shelf-Life and Preserving the Nutritional Value of Pili Nut (Canarium ovatum) in the Form of Flour” for their third year Chemistry Investigative Project.

Their study focused on finding an efficient way to make pili nut flour and to effectively prolong the flour’s shelf life without losing its nutritional value.

To make the flour, the raw pili nuts had to spend 40 hours inside a dehydrator. After that, they were pulverized on layers of clean towels. A mallet was used to crush the dried pili nuts into fine-grained particles. They were left to sun-dry for twelve hours, before being crushed again with a mallet.

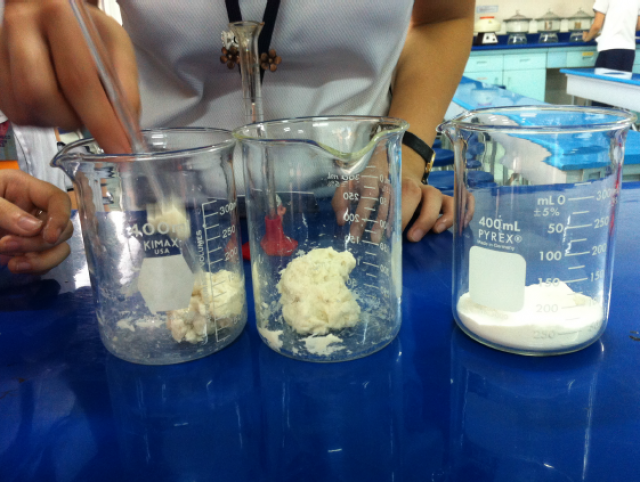

The researchers noted that the pili nut flour they obtained was crumbly and pale yellow in color. Despite the several stages of grinding, the flour produce had a larger particle size when compared to that of all-purpose flour (APF).

They also noted that the pili nut flour was still oily upon touch, hence, arriving at the conclusion that not all of the fats and oils were extracted by the paper towels. When compared to APF, the pili nut flour was heavier and had a distinct aroma.

After creating a few more batches of pili nut flour, the research group sent a 250 gram sample to Qualibet Food Testing Laboratories. The remaining 250 grams of pili nut flour was utilized for testing inside the ICA Chemistry Laboratory.

To test for pili nut flour’s crude protein, the research group used the Kjedahl method. The Kjedahl method is used to estimate the amount of Nitrogen in an ammonia-filled sample. First, a pili nut flour sample was mixed with sulphuric acid and sodium hydroxide, for the release of ammonia gas. That ammonia gas, plus boric acid, would be titrated with standard hydrochloric acid (HCl). The percentage of crude protein was calculated based on the amount of HCl used. In 100 grams of pili nut flour, there is 15.84 % of crude protein.

To test for the total mineral matter, three to five grams of each flour sample were gathered into crucibles and weighed. They were then heated at 6000 C in a muffle furnace for three hours. Samples of pili nuts were also subjected to this process to compute for the total mineral matter. The total mineral matter found in raw pili nuts was 2.94 %, while the total mineral matter found in pili nut flour is 3.64 %.

To test for fat absorption, 1 gram of all-purpose flour, almond flour and pili nut flour were each centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 25 minutes. The free oil was decanted and the weight of each centrifuge tube was noted. In the group’s results, the pili nut flour had the same fat absorption capacity as that of the APF.

To test for overall acceptability, the research group made 5 batches of bread with varying concentrations of all-purpose flour and Pili nut flour. They got 50 respondents to evaluate their pili nut pandesal, in terms of taste, appearance and aroma. Although most of them favored the 100 % all-purpose flour batch, the 50 percent pili nut flour and 50 percent all-purpose flour came out as their second choice.

The researchers admitted that there was a problem in extracting moisture from the pili nuts during the processing into flour. If this hurdle could be overcome, the shelf life of the product could be extended. Nevertheless, the researchers saw greater amounts of protein, minerals, and calories in comparison with other types of bread.

Overall, when compared to bread made from APF and almond flour, pili nut-based bread proved to be a healthier alternative to the classic pandesal. — All photos credit: ICA researchers/TJD, GMA News