Knowing all the angles: Ancient Babylonians used tricky geometry

WASHINGTON - Ancient Babylonian astronomers were way ahead of their time, using sophisticated geometric techniques that until now had been considered an achievement of medieval European scholars.

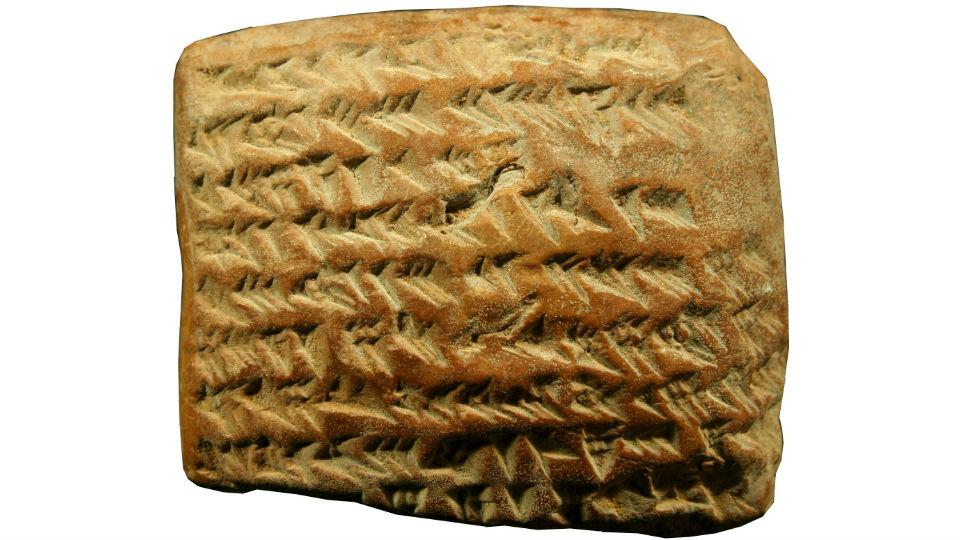

That is the finding of a study published on Thursday that analyzed four clay tablets dating from 350 to 50 BC featuring the wedge-shaped ancient Babylonian cuneiform script describing how to track the planet Jupiter's path across the sky.

"No one expected this," said Mathieu Ossendrijver, a professor of history of ancient science at Humboldt University in Berlin, noting that the methods delineated in the tablets were so advanced that they foreshadowed the development of calculus.

"This kind of understanding of the connection between velocity, time and distance was thought to have emerged only around 1350 AD," Ossendrijver added.

The methods were similar to those employed by 14th century scholars at University of Oxford's Merton College, he said.

Babylon was an important city in ancient Mesopotamia, located in Iraq about 60 miles (100 kilometers) south of Baghdad. Jupiter was associated with Marduk, the city's patron god.

Babylonian astronomers produced tables with computed positions of the planets, Ossendrijver said.

"They provided positions needed for making horoscopes ordered by clients, and they also held the view that everything on Earth - from river levels to market prices, for example grain, and weather - is connected to the motion of the planets. So by predicting the latter they hoped to be able to predict things on Earth," Ossendrijver added.

He noted that the tablets themselves do not mention anything about these astrological applications.

The four tablets, excavated around 1880, were stored at the British Museum in London. The cuneiform characters were impressed in soft clay with a reed stylus and the tablets may have been stored in the scientific library of an astronomer or a temple building, Ossendrijver said.

The tablets contain geometrical calculations based on a trapezoid's area, and its long and short sides. It had been thought that Babylonian astronomers relied only on arithmetical concepts, not geometric ones.

The ancient Greeks also were known for using geometry, but the Babylonian tablets employ it in a more complex, abstract manner.

The research was published in the journal Science. (Reporting by Will Dunham; Editing by Sandra Maler) — Reuters