Diwata Ascending: The benefits of a Filipino space program

At long last, the Philippines is about to take its first independent steps into space with the launch of its first micro-satellite this April.

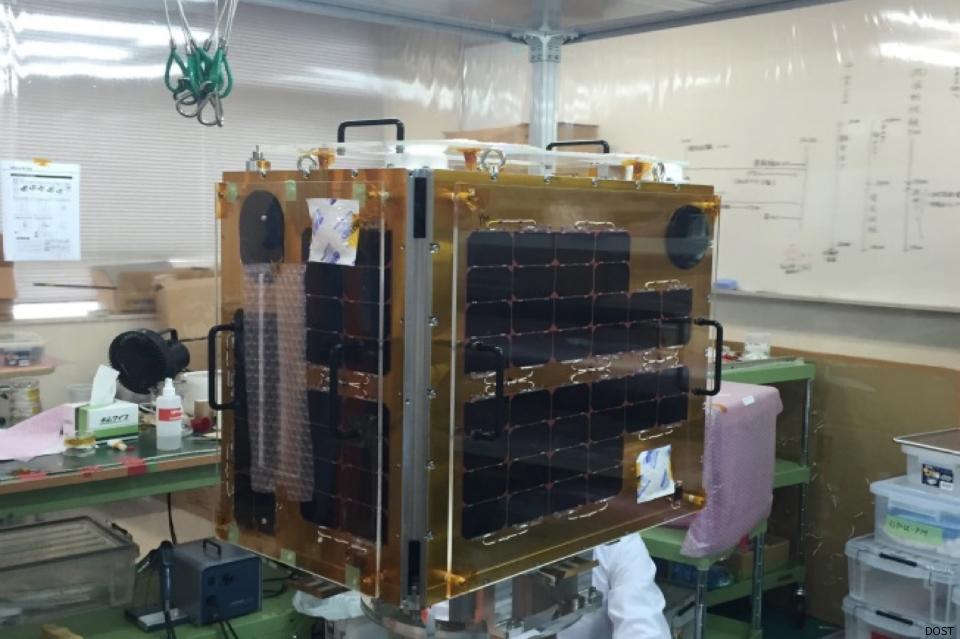

The PHL-Microsat-1 or DIWATA-1 is a low earth orbit (LEO) satellite set to fly 400km above the Earth, serving as a training platform to hone the engineering skills of the Filipino team that built it.

On top of this, Diwata also has the practical purpose of helping monitor weather and agriculture: its sensors will be sending vital images and data back to a facility in Subic, Zambales, for use by local scientists.

But why should the Philippines—a third-world country already saddled with numerous economic and social problems—bother to launch a satellite at all?

The answer, as it turns out, is not in the stars but right under our very noses.

Why the PHL should venture into space

Many of the things we take for granted as we go about our daily lives—from non-stick frying pans and GPS navigation to water purifiers and solar cells—are actually derived from space science.

“Most people don’t realize that a lot of the technology that we use right now came from space technology, from space research,” said Dr. Rogel Mari Sese of the Philippine Space Science Education Program of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST).

But by far one of the most relevant space technologies to the Philippines, a country ravaged by an average of 20 typhoons a year, is weather forecasting.

“The knowledge of knowing where and when a typhoon will hit the country translates to the amount of property and the lives that can be saved through proper information,” Sese said. “And the only way we can get that is through satellites.”

More jobs for Pinoys at home

Space science also means jobs for Filipinos inside the country.

Sese cited a recent study which showed that, for every space-related job in a country, there are at least four non-space-related jobs to support that single person working for the space technology sector.

Non-space-related jobs include those generated in the manufacturing sector, such as production of steel and electronics, as well as those from the services sector.

“If we have, for example, 5,000 people working for the space development program, then that translates to 20,000 people working as a support structure for the space program,” he explained.

Return on investment

“If we invest, say, P2.5 billion a year in space technology, that translates into about P6.5 billion of economic benefits in infrastructure alone,” Sese said. “Put simply, for every P1 we invest in space technology, we get P2.50 in return.”

But in space as in life, good things come to those who wait: the returns, though immense, are not immediate.

“The thing about space technology is that we have to think long-term,” Sese explained. “But of course at the same time, we have to manage the expectations. Filipinos have this short-term view in all problems. Planning for satellites takes years.”

A Philippine space agency

Because of the need for a long-term strategy, Sese and his team have been lobbying Congress for the creation of a national space policy and a national space agency.

The main purpose of such a Philippine space agency would be to serve other government agencies’ needs for space science. Among others, this would include the Department of Agriculture, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and even the Department of National Defense.

PHL lags behind other countries

However, for the Philippines to benefit from space science at all, we must take that important first step to the stars—a journey on which many other countries have long since embarked.

In the ASEAN alone, more than half of the 10 member countries have already launched their own satellites, the most recent being Laos.

Singapore leads the pack with five satellites, while Vietnam has two of its own. Even Indonesia and Malaysia each have satellites, all focused on either Earth monitoring or telecommunications.

“To be honest, [the Philippines] is already behind so it’s about time we do it,” Sese laments.

What might have been, and what could be

Sadly, what many people don't realize is that the Philippines could have led its neighbors in the space race if only it had kept up the early momentum of its scientific advancement: the original Manila Observatory, established in the 1800’s, was renowned for its meteorological and astronomical facilities before these were destroyed in World War II.

Despite the first space race that culminated in the moon landing in 1969, it was only in August 1997 that the Philippines launched Agila 2, a geostationary telecommunications satellite. It was intended for TV and radio broadcasting, but was entirely a private endeavor.

Diwata, however, is a glimmer of hope that all is not yet lost: it is the first independent step in a long but exciting journey which, ultimately, may yet lead to Filipinos taking their rightful place among the stars. – With TJ Dimacali, GMA News