Scholars weigh in on a disruptive presidency

After the Soviet empire crumbled and dictatorships fell in the 1980s and early 90s, a provocatively titled book, "The End of History and the Last Man," came out, capturing the triumphalist zeitgeist of the era. The author, political philosopher Francis Fukuyama, pronounced that in the ideological battles that defined the century, Western-style liberal democracy had finally won out, and there was no turning back. The popular uprising on EDSA in 1986 that evicted the dictator Marcos was a harbinger of this global trend.

Not so fast, according to a less sanguine version of history. Before he became a CNN talking head, Fareed Zakaria was already a political thinker of note, and had warned in a famous essay in 1997 that the wave of democracy, with the power of the vote wielded by the masses, was ushering in its own form of authoritarianism. He called this political model, “illiberal democracy.”

Now here we are in 2017, with Zakaria’s grim warning playing out in elected regimes in Europe, America and the Philippines.

Pundits in America, most of whom were certain of a Democratic victory in 2016, are still reeling from the shock and awe of the first chaotic months of a Trump presidency.

In the Philippines, the electoral victory of Rodrigo Duterte had been more predictable because of the accuracy of public surveys, but the "winnability" of his crass message of violence branded as change had staggered observers more accustomed to candidates who spoke more politely of their intentions. Certainly, something had changed in the electorate as well.

Since then, the international community as well as many Filipinos have been stunned by the ferocity of his drug war, which was exactly what he had vowed during the election. This was one campaign promise that was kept.

As Duterte maintains his high approval ratings in public surveys, he is still a puzzle to many, even to supporters who struggle to explain the contradictions, including the claim of safer streets amidst record-setting murder rates.

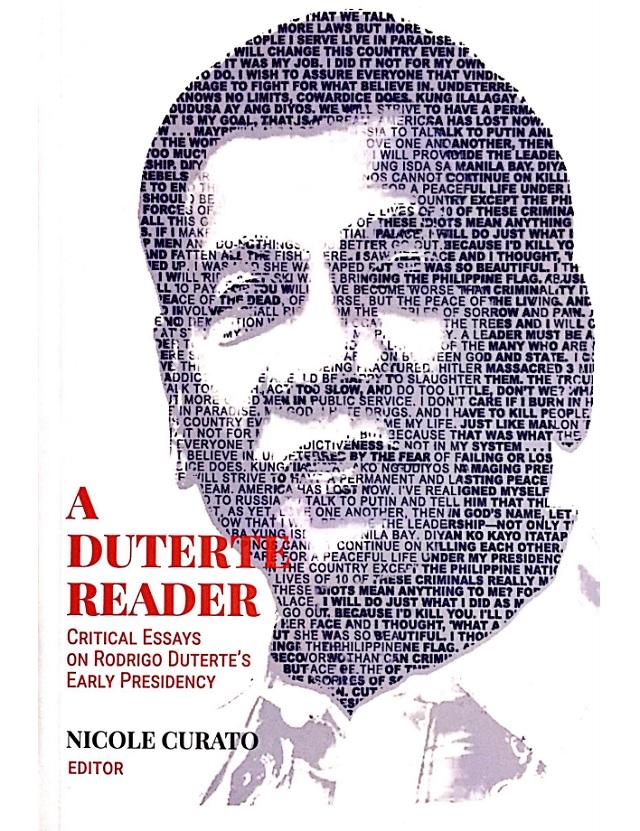

Into this vacuum of understanding enters “A Duterte Reader,” a timely volume of “critical essays on Rodrigo Duterte’s early presidency” published by the Ateneo University Press.

Edited by Nicole Curato, a sociologist and frequent explainer of current politics in the news media, this volume of short essays by varied scholars looks at the rise and early reign of what’s come to be known as “Dutertismo,” a brand of leadership that all the writers agree has elements that the country has never seen before, not the least of which is representation of Mindanao in Malacañang.

Underdog outsider

Those southern roots gave Duterte an underdog outsider’s image that propelled his candidacy across a country that apparently was tiring of “northern elites.” In their sympathetic chapter “The Mindanaoan President,” Mindanao-based scholars Jesse Angelo Altez and Kloyde Caday describe the hope that Duterte means for the neglected “tri-people of Mindanao,” with fond recollections of his kindness to Lumads and his claim of blood links to Moros without being threatening to fellow Christians with Bisayan heritage like him.

The authors’ narrative of Davao as a “progressive city in terms of human development and security” is typical of the rose-colored view by supporters, making no reference to the not-so-mysterious killings of criminal suspects in Davao that were an essential ingredient in Duterte’s local strongman rule. To what extent that brutality could explain his family’s hold on power in Mindanao’s largest city is not tackled in this chapter, and neither is its relevance to the current Dutertismo.

Perhaps more appropriately, that aspect of Davao is left to Nathan Quimpo, who possesses a PhD in political science but whose expertise on Mindanao could be attributed as much to his long experience as a communist organizer in the region during Martial Law.

Quimpo was still in the communist movement when Davao became a bloody laboratory for urban insurgency. It was in this environment that Duterte first became mayor in 1988, and quickly imposed his will by “securitizing” illegal drugs, a term used by Quimpo to describe how narcotics were projected as a threat to society, justifying extraordinary measures to quell it.

It worked in Davao to concentrate the means of violence in one man, who was, in Quimpo’s words – even if no direct links could be proven – the “inspirational beacon and virtual godfather” of the so-called Davao Death Squad, “the country’s most murderous private army in the post-Marcos era.”

Davao playbook

As Quimpo quotes another political scientist, “Duterte makes abundantly clear that there can be security, but only he can provide it. Security is provided according to his personal ideas of justice and adequateness. In his political symbolism, Duterte is clearly above the law.” That was written in 2009. One can discern a Davao playbook in what has been unfolding today in many cities around the country, the profanity-laced threats to kill followed by actual murders by unknown assailants.

To Quimpo, the killings are not meant to eradicate drugs, which he doubts ever reached narco-state levels in the country. Instead, projecting drugs as an existential threat to the nation has compelled much of the public to accept the violence, and see Duterte as the nation’s savior. The killings were never about drugs, but power and its preservation: “It is boss rule in pure form.”

Walden Bello, another veteran of anti-Marcos leftist politics with a doctorate, writes about Duterte as a “fascist original” with a gangster charm. Two aspects make Dutertismo unique in the annals of right-wing dictatorships – his alliance with communists; and the absence of hesitation in using violence from the outset, with bodies littering the streets even before his inauguration. He contrasts that with Marcos’ “creeping fascism” where the curtailment of civil liberties preceded killings. Murders then were often more subtle affairs where bodies were not displayed with signs but tucked away in unmarked graves.

All of this, Bello writes, was enabled by an “electoral insurgency” powered by a disillusionment with the failed promises of EDSA, a fiasco embodied by an “elite monopoly of the electoral system” and “neoliberal economic policies.” That explanation, however, assumes that many voters actually did structural analysis, and does not account for leftist and independent voices like Bello’s being heard inside Congress as partylist representatives, even if they are small minorities. An elite oligopoly then of the electoral system?

And if true, Duterte must have pulled a fast one on voters, as he and his family have been the masters of local electoral monopoly in Davao. Whether or not all the promises of EDSA failed, its latest personification – Noynoy Aquino – ended his presidency with high approval ratings. Bello is on the mark in claiming that Dutertismo’s rise was as much an attraction to a new form of personal charisma as it was a rejection of anything.

Rise of trolls

Perhaps analysts of electoral insurgencies, whether they occur in America or backwaters like the Philippines, do not give enough credit to – or do not heap enough blame on – the insidious effects of social media, how it enabled political machines to bypass liberal media gatekeepers of information. Facebook especially allowed fake news and false narratives to proliferate, only belatedly recognizing its responsibility as the most pervasive information platform in history.

In their chapter on “The Rise of Trolls in the Philippines,” Jason Vincent Cabañes and Jayeel Cornelio try to look at the positive side of social media trolls, how they could “deepen the quality of conversations in the public sphere,” and “sharpen public opinion.” It is a mistake, they argue, to dismiss and block trolls, a sign of moral panic by elites. Instead, we need to listen to and even engage them, at least those who are not professional trolls and bots. And they call for “a more democratic media” that reflects more diverse public opinions.

The problem with this view is real-world experience. Many social media users I know would love to engage with others with whom they have honest disagreements. But how about the amateur trolls who curse you, heap hate on you for your opinion, and threaten you and your family? There seem to be many more of those in the public sphere than the ones who are willing to debate and reason with you. The effect of that vitriol on the targets of hate, which includes almost anyone who dares to criticize the president, is to create privacy settings around your comments, forming so-called echo chambers where you hear only from your friends. I admit I am one of the guilty ones here. But should I be blamed for not wanting to be bombarded by profanity-spewing haters for what I thought were valid observations?

Fake news is barely referenced in this chapter on trolls, but I hope that’s not an underestimation of its significance in recent political change. There are no known academic studies yet of fake news in the Philippines, which is a shame considering its crucial role now in the formation of support for the Duterte regime.

We have long known that fake news is a favorite weapon of Russia’s Vladimir Putin in influencing public opinion in his country and others that he wants to troll. A US study by Buzzfeed showed that Facebook engagement with fake news overtook mainstream news content in the weeks before the US elections, probably helping Donald Trump secure a narrow electoral-college victory over Hillary Clinton, whose followers were not as adept in this realm.

Pressure on Facebook in France to crack down on fake news led the social media giant to block 30,000 fake news sites, most of which supported the right-wing candidacy of Marine Le Pen, who lost the election. No such pressure exists in the Philippines, where free access by telcos to Facebook has encouraged tricksters of all kinds to populate news feeds with falsehoods, like blaming the Marawi crisis on the imprisoned Leila de Lima.

Targeting liberal democracy

Several of the writers in “A Duterte Reader” assert that Dutertismo’s target is really liberal democracy, with its constitutional protections for press freedom, human rights, and due process – hallmarks of the post-Marcos era. Hence the attacks as well on the memory of EDSA 1986, the subject of Cleve Arguelles’ essay.

All of these, including Liberal with a capital L, comprise perceived roadblocks to a political project that Bello and others say include the perpetuation of power.

Nicole Curato calls this vision of the future an “illiberal fantasy,” since Duterte is planting the seeds of his own failure. Sheila Coronel’s essay elaborates with her dissection of the police, the enforcer of Duterte’s drug war with a long notoriety as among the most corrupt and abusive institutions of government, not the ideal instrument for inspiring confidence in the new administration. Her current research reveals that enterprising policemen have used the drug war to expand their criminal activities in a variety of ways. (Disclosure: Coronel and I are long-time colleagues at the PCIJ)

Ronald Holmes, a De La Salle University professor and president of the polling firm Pulse Asia Research, explains that beyond the high approval ratings of Duterte, public surveys also show that many Filipinos in fact fear that someone in their family will be a future victim of an extrajudicial killing.

The disdain for liberal democracy, coupled with a strident anti-Americanism, is what really binds Duterte to communists, and not any ideological kinship, despite Duterte’s self-identification as a socialist, according to Lisandro Claudio and Patricio Abinales. As such, Duterte combines the “two extremes of authoritarian and communist nationalism.”

But Duterte’s warmth towards Donald Trump may demonstrate that his dislike for America is as much a reaction to criticism by former President Barack Obama as it was to any reading of history. Claudio and Abinales point out that Duterte does not appear that he will cut military ties to the US any time soon, a leftist priority, nor has he signaled that he will shift economic policy away from the global free trade regime that the communists despise.

Much has changed since the communist ecstasy of Duterte’s first months in office, when he was the first president in 16 years not to have his effigy burned to coincide on the day of the SONA. Emerson Sanchez traces the erosion of his alliance with the Left, which was accelerated by Duterte’s embrace of the Marcoses to the point where Duterte’s effigy is now routinely a part of street rallies, placing him in the same hall of shame with previous “counterrevolutionary” leaders.

Style more than substance

If anything, the chapters by Carmel Veloso Abao and Anna Cristina Pertierra assert, Duterte’s populism is more a matter of style than substance, much like the Joseph Estrada presidency but with much more violence. Even one of Duterte’s most awaited populist promises, the end of labor contractualization, has been abandoned in favor of a watered down version that unions have condemned.

Duterte’s men have learned from the short-lived Estrada presidency that their guy needs a protective mass movement around him, real feet on the ground instead of hyperactive Facebook groups. That is why the ex-NPA commander and now Duterte lieutenant Jun Evasco has been tasked with setting up the Kilusang Pagbabago. Without a clear ideological glue or platform, it remains to be seen if Duterte’s charisma will be enough to keep that nascent movement viable enough to compete with more established political machines.

In the meantime, even without a grassroots organization, Dutertismo is alive and well. Quimpo, Bello, and others argue that’s what the violence and threats serve to do – silence dissent, create fear, and enable political control. But after a year of trying to figure him out, dissenters on Facebook, in the church, and even the Senate are starting to find their voices.

Most of the articles in this book were written before the president’s first year in office lapsed, hence the tone of resignation in some of the pieces about the President’s hegemony. Some possible turning points have occurred since, including the CCTV-recorded abduction by police of 17-year-old Kian delos Santos and the nationally televised Senate hearing on shabu smuggling through the Bureau of Customs, with a special appearance by the president’s son, Paolo Duterte, vice mayor of Davao.

Ironically, it was in the first Mindanaoan president’s first year in office that the greatest crisis in Mindanao in years broke out, the urban warfare ignited by a small armed group that still controls parts of a decimated Marawi more than three months later.

Just as significant for the future of Duterte’s illiberal experiment is what hasn’t happened – traffic has not abated, no peace agreement signed with the Left, the drug war has not been won after thousands of killings and may not be winnable during his term, as the President himself has remarked. The economy has not improved. The big question is how long Dutertismo can sustain its popularity without delivering on its promises, or at least the non-lethal ones.

The Duterte Reader already cries out for a Part Two, this time perhaps with authors who have actually been embedded with Duterte followers and done focus-group discussions on why the steadfast support for what many around the world perceive as abhorrent human rights violations. Were many Duterte voters previously PNoy supporters, and why did they choose the most “un-EDSA” of the candidates?

There must also be researchers who are working on the inside story of the brilliantly unpredictable Duterte presidential campaign, the debates within on the inflammatory and surprisingly resonant messaging. Will that be a template for campaigns of the future?

Beyond the founder

Scholars can start looking beyond the founder of Dutertismo and begin discerning its long-term impact on society. Does liberal democracy have a future, and is this illiberal present just a speed bump on what Fukuyama would say is an endless liberal highway?

I’ve sometimes wondered what our politics would have been like if Cory Aquino did not die when she did, in August 2009, and her son Noynoy’s candidacy was not launched on a wave of emotion and 1986 nostalgia. Joseph Estrada, who placed second in the 2010 election, might have been a repeat populist president with little interest in reform, followed then by another populist. Or would the field after Estrada have been riper for a bland reformist technocrat like Mar Roxas? That’s only worth pondering in the context of a theory of seesawing political fortunes between presidential populism and reformism, the subject of Julio Teehankee’s chapter.

Will there be an accounting for the killings after Duterte’s six years and how could that take shape? Are police officers in drug war battlegrounds worried?

And what of President Duterte’s profane and menacing language, and its effects on future national discourse and ordinary conversations of the youth?

Finally, are Filipino values changing, or in the minds of more than a few, being destroyed? Are online meanness and street killing becoming more acceptable and even normal? As haters threaten journalists and critics, is there a future for free speech?

Even as I write this, I am thinking of the trolls who will attack me just because of the questions this review raises. Should I ignore, block, or delete? Or as a chapter in this book proposes, engage? Depends on whether we can find a common civil language for engagement, and safe spaces for healthy debate. The future of books like this along with all other critical research and commentary on public affairs may well depend on that as well. —JST, GMA News