Coming of age under Martial Law

I was in 2nd year high school in an exclusive convent school when Martial Law was declared. I remember waking up and looking out my bedroom window, waiting for the tanks to roll down our street, and feeling rather disappointed when I didn’t see any. All day, Sec. Francisco Tatad was on all the TV channels, imposing in grainy black-and-white. He recited PD 1081 for all to follow and implement. I didn’t really care. I was 15 and was more concerned about not being noticed by boys, and not being allowed to attend parties yet. Oh no! I thought. What would ML do to my social life? My parents would never let me out after this! I would be doomed to spinsterhood! As I grew older and entered college, my concerns matured along with me. It was then that I truly felt the impact of ML on my personal life. I was still in the same convent school, and in many ways, I had a "normal" college experience, complete with all the trappings that come at that particular period of one's life: parties (of course, within the bounds of curfew), boyfriends, schoolwork, and the pressure of figuring out what I wanted to do with my life. But we also had a very progressive and politicized dean of college, Sr. Mary John Mananzan. It was impossible to be in the same room with her and not be awakened to social realities. We were encouraged to join, if not lead, rallies and fora to discuss social issues and all the “ismos”—feudalismo, capitalismo, imperialismo.

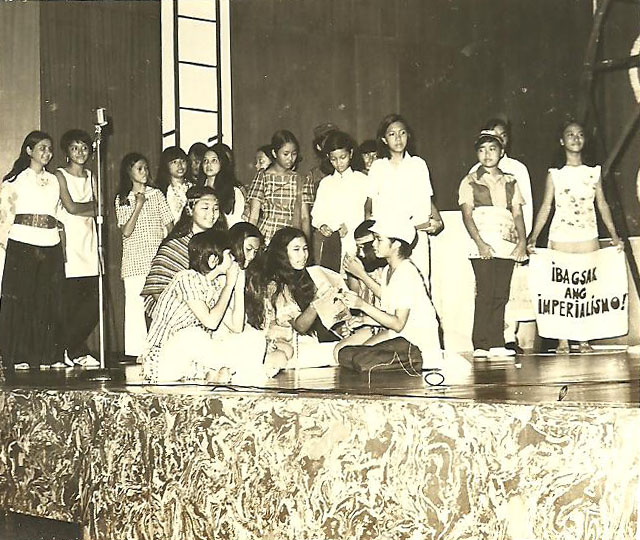

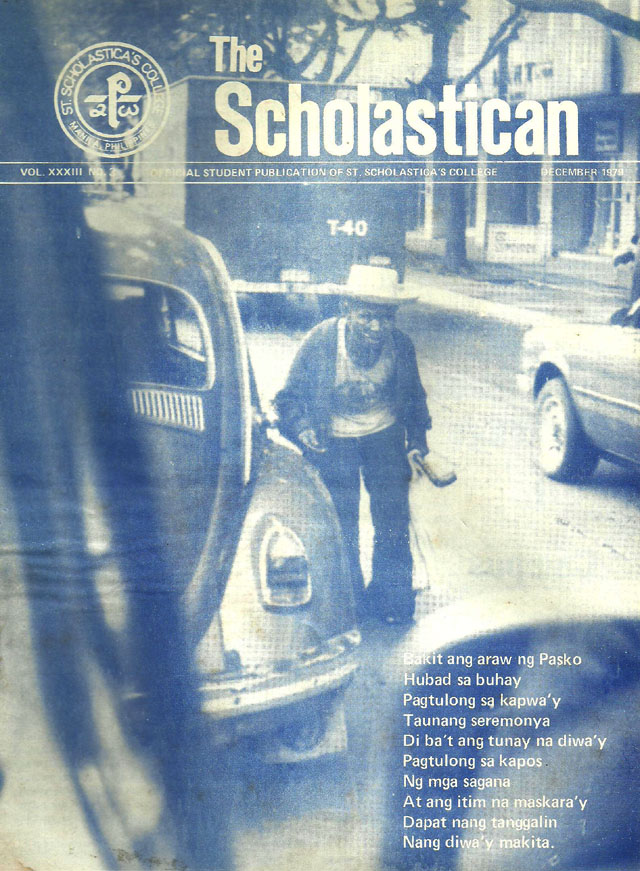

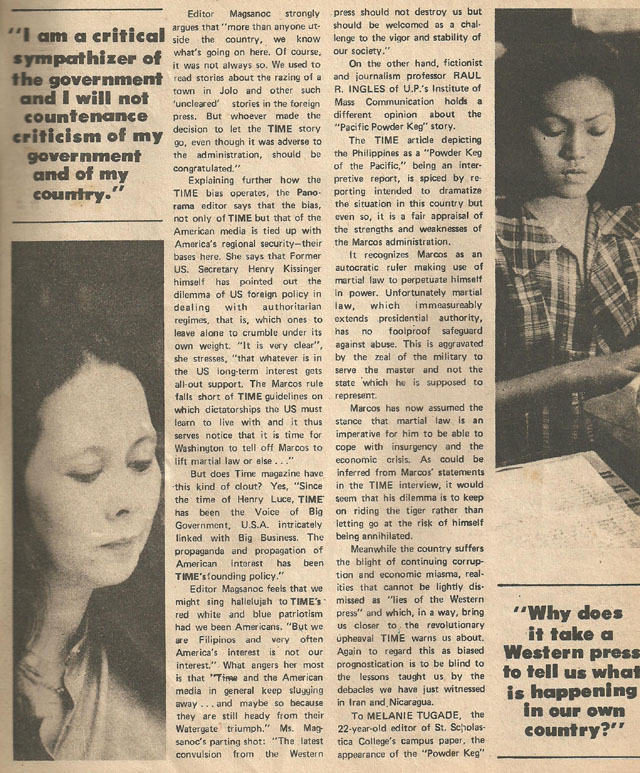

Field trips meant socializing with the political detainees in Bicutan—at that time, Satur Ocampo, Ed dela Torre, to name a couple. If not, we joined the squatters in their homes just behind St. Scho, sharing a meal and talking to them about life. After classes, we held study groups in secret to learn about Karl Marx’s philosophies and why the Philippines was so poor and oppressed. As editor-in-chief of The Scholastican, our school organ, I participated in several congresses of the College Editors’ Guild of the Philippines and had a taste of midnight study groups where we discussed the “ismos” further and formed political alliances based on ideology and raging hormones (a deadly combination). As it turned out, most of my colleagues ended up in top posts in multinational corporations or in politics—the very things we rallied against during those midnight study groups. Some of my friends then thought I was a “radical.” My parents were afraid for me because they read the articles we churned out for The Scholastican, and thought that I could get arrested for them. But I was tame compared to the others. Some of my contemporaries joined the UG (Underground) for “The Cause.” Some managed to get back and join civil society. One of them, my batchmate Cherith Dayrit who was Student Council President, was killed in an encounter with the military. After college, I joined the workforce and became a follower of capitalist teachings. I pined for the lost idealism, the academic debates. So after Ninoy Aquino was killed and rallies happened every week in Ayala Avenue, I was there. When People Power happened, I left my 3-month old son with my mother-in-law and, together with my husband, marched to EDSA to link hands with strangers all fighting for the same cause. When the dictatorship fell, it was a great triumph for all of us. As I look back on those years now as a mother and no longer the idealistic young woman that I was, I realize I could have lived with Martial Law, if only Marcos stayed true to his dream and vision for the Philippines. But his corruption and thirst for power ate up that dream. Now, it saddens me to see that what we fought for in EDSA is being diminished by the same greed and corruption that we wanted to escape from during ML. People forget so easily, but perhaps it’s up to us—the youth of that time—to remember for everyone else. - YA, GMA News Photo and clippings courtesy of the author From top to bottom: A school play protesting one of the -ismos ailing Philippine society, cover of the campus organ depicting social ills, and a clipping from WHO magazine that featured a blurb from the author (right photo) about media censorship Melanie Tugade-Lago is an insurance agent, financial adviser, and mother of three who spends her free time cooking, doing arts and crafts, and making sure her children abide by their curfew. She insists that her Martial Law experience is boring compared to what others went through, but she wrote it anyway.

Field trips meant socializing with the political detainees in Bicutan—at that time, Satur Ocampo, Ed dela Torre, to name a couple. If not, we joined the squatters in their homes just behind St. Scho, sharing a meal and talking to them about life. After classes, we held study groups in secret to learn about Karl Marx’s philosophies and why the Philippines was so poor and oppressed. As editor-in-chief of The Scholastican, our school organ, I participated in several congresses of the College Editors’ Guild of the Philippines and had a taste of midnight study groups where we discussed the “ismos” further and formed political alliances based on ideology and raging hormones (a deadly combination). As it turned out, most of my colleagues ended up in top posts in multinational corporations or in politics—the very things we rallied against during those midnight study groups. Some of my friends then thought I was a “radical.” My parents were afraid for me because they read the articles we churned out for The Scholastican, and thought that I could get arrested for them. But I was tame compared to the others. Some of my contemporaries joined the UG (Underground) for “The Cause.” Some managed to get back and join civil society. One of them, my batchmate Cherith Dayrit who was Student Council President, was killed in an encounter with the military. After college, I joined the workforce and became a follower of capitalist teachings. I pined for the lost idealism, the academic debates. So after Ninoy Aquino was killed and rallies happened every week in Ayala Avenue, I was there. When People Power happened, I left my 3-month old son with my mother-in-law and, together with my husband, marched to EDSA to link hands with strangers all fighting for the same cause. When the dictatorship fell, it was a great triumph for all of us. As I look back on those years now as a mother and no longer the idealistic young woman that I was, I realize I could have lived with Martial Law, if only Marcos stayed true to his dream and vision for the Philippines. But his corruption and thirst for power ate up that dream. Now, it saddens me to see that what we fought for in EDSA is being diminished by the same greed and corruption that we wanted to escape from during ML. People forget so easily, but perhaps it’s up to us—the youth of that time—to remember for everyone else. - YA, GMA News Photo and clippings courtesy of the author From top to bottom: A school play protesting one of the -ismos ailing Philippine society, cover of the campus organ depicting social ills, and a clipping from WHO magazine that featured a blurb from the author (right photo) about media censorship Melanie Tugade-Lago is an insurance agent, financial adviser, and mother of three who spends her free time cooking, doing arts and crafts, and making sure her children abide by their curfew. She insists that her Martial Law experience is boring compared to what others went through, but she wrote it anyway.