ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered By: Lifestyle

Lifestyle

The Holy Shroud: A pilgrimage to Turin

Text & photos by ALICE SUN-CUA

Turin, Italy It was cold and almost freezing when we stepped out of the heated train at the Stazione di Porta Nuova in Turin, a city in the northwest region of Italy. My husband Alex and I came from Milan, about two hours away, and found ourselves shivering at the station that early morning; the temperature gradient from warm to very cold was a shock to our unaccustomed systems. After orienting ourselves with the city grid, off we went, walking briskly to generate some body heat in search of the Cattedrale di San Giovanni Battista (Cathedral of St. John the Baptist), where the Holy Shroud of Turin was supposedly kept. We passed by modern edifices and quiet streets with very little traffic, and so few people going about. It must be the weather, Alex commented, as light rain started to fall. We made it to the church doors just in time to hear the torrential pouring of what sounded like a storm outside the portals of the Renaissance cathedral. The darkness inside initially made it difficult to move, but after a few minutes our eyes could make out the pews, and at the left side near the entrance, a softly-lighted area. We drew near that corner, and beheld a familiar sight: a life-sized reproduction of the Holy Shroud, in both its positive and negative depictions.  The Holy Shroud was supposedly the linen provided by Joseph of Arimathea that was wrapped around the dead body of Jesus when he was taken down from the cross. The reproduction was 3 ft. by 14 ft and had, on one side, the imprint of a man with a beard whose face and head were filled with bruises and blood. His hands were crossed in the groin, and blood streaks were compatible with lashings, including a big wound on his right upper abdomen; from his hands and feet, blood oozed from crucifixion nails. On the other side were traces of whippings on his back. The Holy Shroud has attracted a lot of controversy and has been the subject of many scientific studies including carbon dating, irradiation, and blood and DNA analysis. Many methods too, including bas relief painting, dust-transfer techniques, and oxidation were done to duplicate the image on the shroud. It is said that the linen was brought to France from Jerusalem during the 13th century by the Crusaders, and was kept in a chapel in Chambery. When fire broke out in the monastery, the cloth was singed in the folded areas. Silver also melted into it, hence there were regular triangular areas throughout its length. When Vittorio Emanuele I of Savoy (the Savoys being the royal family of Turin) became King, he requested for the cloth and since then the shroud has been kept in Turin.

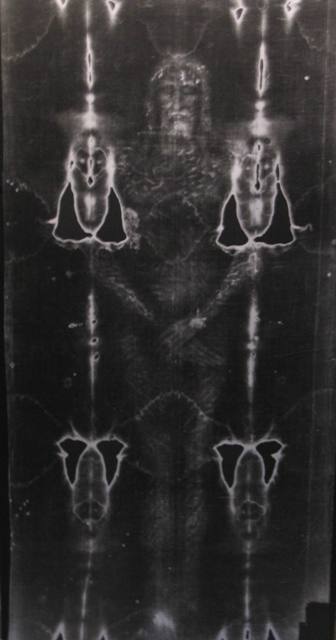

The Holy Shroud was supposedly the linen provided by Joseph of Arimathea that was wrapped around the dead body of Jesus when he was taken down from the cross. The reproduction was 3 ft. by 14 ft and had, on one side, the imprint of a man with a beard whose face and head were filled with bruises and blood. His hands were crossed in the groin, and blood streaks were compatible with lashings, including a big wound on his right upper abdomen; from his hands and feet, blood oozed from crucifixion nails. On the other side were traces of whippings on his back. The Holy Shroud has attracted a lot of controversy and has been the subject of many scientific studies including carbon dating, irradiation, and blood and DNA analysis. Many methods too, including bas relief painting, dust-transfer techniques, and oxidation were done to duplicate the image on the shroud. It is said that the linen was brought to France from Jerusalem during the 13th century by the Crusaders, and was kept in a chapel in Chambery. When fire broke out in the monastery, the cloth was singed in the folded areas. Silver also melted into it, hence there were regular triangular areas throughout its length. When Vittorio Emanuele I of Savoy (the Savoys being the royal family of Turin) became King, he requested for the cloth and since then the shroud has been kept in Turin.  Just below the brightly-lit yellowish positive reproduction were more thought-provoking and heart-stopping pictures: the negatives of the Holy Shroud. Said to be taken by amateur photographer Secondo Pia in 1898, these were the popular and iconic images of the Holy Shroud. In black and white but sharper now, a distinct countenance with its eyes closed could be clearly limned. The subject’s face was bruised, and its nose fractured. The bony hands and feet had old blood stains and wounds. But what struck me most was the facial expression: sad, desolate, and seemingly reproachful. It was definitely cold in the cathedral. Nobody seemed to be around, and the darkness deepened as the rain continued to pour. Gothic atmosphere, indeed, as my imagination galloped wildly. The hairs on my neck stood on end, as I contemplated the vision in front of me. I forced myself to turn around to look for Alex, and nearly collided with him, as he was also standing behind me, looking wide-eyed at the black and white depiction. Was this the real thing or not? A popular devotion to the Holy Shroud had grown, and to believers, it was real. We walked towards the altar where the Capella della Santa Sindone (Chapel of the Holy Shroud) was, expecting to see the original cloth. But the chapel was not only cordoned off; it was encased in thick glass. We could only peer through the dark, and later discovered that the real cloth was kept in a temperature-controlled room to delay its decay. I could only see thick maroon damask curtains, although our guide book said the cloth was laid out in an ornate coffin. It was now rarely taken out except on special occasions, most of the time upon the request of the Pope. Soon enough, I heard several voices, and saw a group of tourists, led by their guide, coming towards the chapel. Alex and I went to the cathedral museum shop and got some Holy Shroud medals for friends, who, to this day, cherish them. The rain had stopped when we stepped out of the cathedral, and it was a good time to hie off to see the Mole Antonelliana, Turin’s emblematic building. Named after its architect Alessandro Antonello, it stands 167 meters high and is the world’s tallest museum. It started out as a Jewish synagogue in 1863 built with stone and masonry, with a strange-looking dome and a pointed top. After much controversy, the Mole museum was finally inaugurated in 1908. It was lunch time, though, and we had to wait a bit for the edifice to open at 2 PM. Alex and I looked for a park nearby and had a quiet lunch: salad with crispy chicken and some beer and soda, all bought from the nearby PAM’s grocery store in Milan where we were based. There were colorful postcards for sale at a nearby kiosk, and I thought it was a good time to write and address some to my mother and friends. I was surprised to discover that my fingers were too stiff to hold a pen properly; it must have been that cold! Alex tried chafing a bit of warmth into my numb fingers with his hands, and we had a good laugh about fingers and noses falling off without our knowing it. The Mole Antonelliana was a huge building with a glass elevator that could take one to an observation deck at the top for panoramic views of Turin. But we were more intrigued by the National Museum of Cinema on the first floor, showing almost everything about movies. There were experimental movies done by Thomas Edison, and more modern ones shown in a perpetual motion movie reel, including surreal venues for movies, such as a cave. Most of the movies were dubbed in Italian. From the Mole we marched off to the River Po that wound through Turin. Along the way we saw posters of the 2006 Winter Olympics, which Turin hosted successfully. We reached the river and discovered that there were medieval-looking stone bridges spanning it. We crossed the Vittorio Emanuel Bridge, and from the other side we exclaimed over the beautiful scene that we left behind. The river was misty, as light rain was falling. But just as suddenly the sun shone, and everything – the water, the bare trees lining its banks, and the palaces far away – became iridescent.

Just below the brightly-lit yellowish positive reproduction were more thought-provoking and heart-stopping pictures: the negatives of the Holy Shroud. Said to be taken by amateur photographer Secondo Pia in 1898, these were the popular and iconic images of the Holy Shroud. In black and white but sharper now, a distinct countenance with its eyes closed could be clearly limned. The subject’s face was bruised, and its nose fractured. The bony hands and feet had old blood stains and wounds. But what struck me most was the facial expression: sad, desolate, and seemingly reproachful. It was definitely cold in the cathedral. Nobody seemed to be around, and the darkness deepened as the rain continued to pour. Gothic atmosphere, indeed, as my imagination galloped wildly. The hairs on my neck stood on end, as I contemplated the vision in front of me. I forced myself to turn around to look for Alex, and nearly collided with him, as he was also standing behind me, looking wide-eyed at the black and white depiction. Was this the real thing or not? A popular devotion to the Holy Shroud had grown, and to believers, it was real. We walked towards the altar where the Capella della Santa Sindone (Chapel of the Holy Shroud) was, expecting to see the original cloth. But the chapel was not only cordoned off; it was encased in thick glass. We could only peer through the dark, and later discovered that the real cloth was kept in a temperature-controlled room to delay its decay. I could only see thick maroon damask curtains, although our guide book said the cloth was laid out in an ornate coffin. It was now rarely taken out except on special occasions, most of the time upon the request of the Pope. Soon enough, I heard several voices, and saw a group of tourists, led by their guide, coming towards the chapel. Alex and I went to the cathedral museum shop and got some Holy Shroud medals for friends, who, to this day, cherish them. The rain had stopped when we stepped out of the cathedral, and it was a good time to hie off to see the Mole Antonelliana, Turin’s emblematic building. Named after its architect Alessandro Antonello, it stands 167 meters high and is the world’s tallest museum. It started out as a Jewish synagogue in 1863 built with stone and masonry, with a strange-looking dome and a pointed top. After much controversy, the Mole museum was finally inaugurated in 1908. It was lunch time, though, and we had to wait a bit for the edifice to open at 2 PM. Alex and I looked for a park nearby and had a quiet lunch: salad with crispy chicken and some beer and soda, all bought from the nearby PAM’s grocery store in Milan where we were based. There were colorful postcards for sale at a nearby kiosk, and I thought it was a good time to write and address some to my mother and friends. I was surprised to discover that my fingers were too stiff to hold a pen properly; it must have been that cold! Alex tried chafing a bit of warmth into my numb fingers with his hands, and we had a good laugh about fingers and noses falling off without our knowing it. The Mole Antonelliana was a huge building with a glass elevator that could take one to an observation deck at the top for panoramic views of Turin. But we were more intrigued by the National Museum of Cinema on the first floor, showing almost everything about movies. There were experimental movies done by Thomas Edison, and more modern ones shown in a perpetual motion movie reel, including surreal venues for movies, such as a cave. Most of the movies were dubbed in Italian. From the Mole we marched off to the River Po that wound through Turin. Along the way we saw posters of the 2006 Winter Olympics, which Turin hosted successfully. We reached the river and discovered that there were medieval-looking stone bridges spanning it. We crossed the Vittorio Emanuel Bridge, and from the other side we exclaimed over the beautiful scene that we left behind. The river was misty, as light rain was falling. But just as suddenly the sun shone, and everything – the water, the bare trees lining its banks, and the palaces far away – became iridescent.  The Piazza Vittorio Veneto with its statue of the Savoy king, Vittorio Emanuel I, was seen clearly along with the two statues of women in flowing robes representing Faith and Religion. The backdrop also had the beautiful neo-classic Chiesa Gran Madre di Dio (Church of the Great Mother of God), built in 1818, standing solemnly with its Roman columns in its tympanum (front) and round roof. The large Latin letters, ORDO POPVLVS QVE TAVRINVS OB ADVENTVM REGIS (“The nobility and the people of Turin for the return of the King”) were engraved on the thick lintel above the columns, referring to the return of the monarch from Sardinia to Turin. Bewitched by the quiet stone paths that lined the River Po, Alex and I took the time to slowly walk along the water’s edge, registering the icy breeze that whipped our cheeks, and the bare trees that looked more wintry than spring-like. We felt as if we did not have any care in the world, and there was no need to hurry anywhere. Indeed, we gave thanks for these moments of quiet and grace. – YA, GMA News

The Piazza Vittorio Veneto with its statue of the Savoy king, Vittorio Emanuel I, was seen clearly along with the two statues of women in flowing robes representing Faith and Religion. The backdrop also had the beautiful neo-classic Chiesa Gran Madre di Dio (Church of the Great Mother of God), built in 1818, standing solemnly with its Roman columns in its tympanum (front) and round roof. The large Latin letters, ORDO POPVLVS QVE TAVRINVS OB ADVENTVM REGIS (“The nobility and the people of Turin for the return of the King”) were engraved on the thick lintel above the columns, referring to the return of the monarch from Sardinia to Turin. Bewitched by the quiet stone paths that lined the River Po, Alex and I took the time to slowly walk along the water’s edge, registering the icy breeze that whipped our cheeks, and the bare trees that looked more wintry than spring-like. We felt as if we did not have any care in the world, and there was no need to hurry anywhere. Indeed, we gave thanks for these moments of quiet and grace. – YA, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular