Where emperors sleep: Japan's keyhole-shaped burial mounds

At this specific time of the year, the world's graveyards come alive and turn into a melting pot of spirituality and family re-connection, all because of All Souls' Day. And though not popularly associated with this holiday, it should well be remembered that some of the most famous and jaw-dropping tourist destinations in the world are, in the first place, ancient graveyards.

There are of course the familiar, time-tested pyramids of Giza, the final resting place of Egypt's pharaohs. There is also India's Taj Majal, built by a Mughal emperor in memory of his wife; and Cambodia's Angkor Wat, originally intended as a Hindu temple of the Khmer empire and eventually turned into a mausoleum.

But if you happened to live centuries ago in Japan, and were fortunate enough to have had royal blood run through your veins, you also got to be buried in a sprawling ancient imperial burial site called a tumulus or kofun ("old mounds").

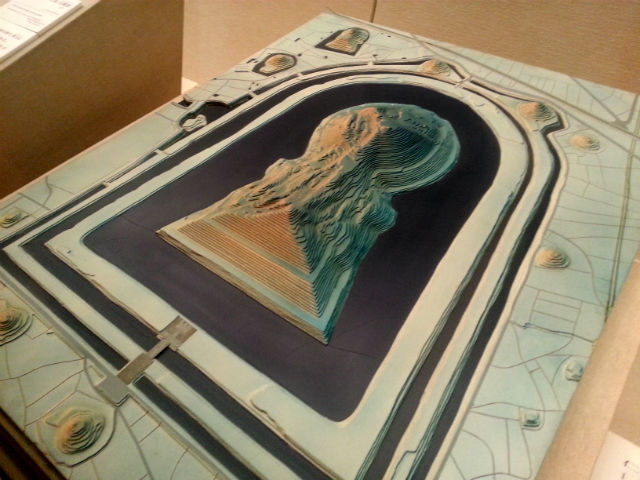

Japan's tumuli are expansive ancient chambered burial mounds, some of them with a keyhole shape, reserved for Japan's emperors, empresses, and other prominent members of the empire. The biggest of the keyhole-shaped tombs is nestled near the outskirts of the ancient city of Sakai, inside the Osaka prefecture, southwest of Tokyo, and is thought to be the final resting place of Nintoku, Japan's 16th emperor.

The Nintoku-ryo tumulus is one of almost 50 tumuli collectively known as "Mozu Kofungun" clustered around the city, and covers the largest area of any tomb in the world. Built in the middle of the 5th century by an estimated 2,000 men working daily for almost 16 years, the Nintoku tumulus, at 486 meters long and with a mound 35 meters high, is twice as long as the base of the famous Great Pyramid of Pharaoh Khufu (Cheops) in Giza.

A keyhole-shaped tumulus is basically made up of two sections: a circular mound at the rear where the sarcophagus of the deceased imperial member is buried; and connected to it a rectangular (more like a trapezoidal) mound where ceremonies and rituals are performed during the burial.

The 470,000-sq-meter Nintoku tumulus mounds, just like the other relatively larger tumuli, were created by digging around it, eventually creating a bell-shaped depression that forms the perimeter of the tumulus, that in time got filled up with water and turned into an instant moat, protecting the grave site from easy access. Over time as well, the tumulus and its 2.7-kilometer, bell-shaped perimeter naturally flourished with thick flora and diverse fauna.

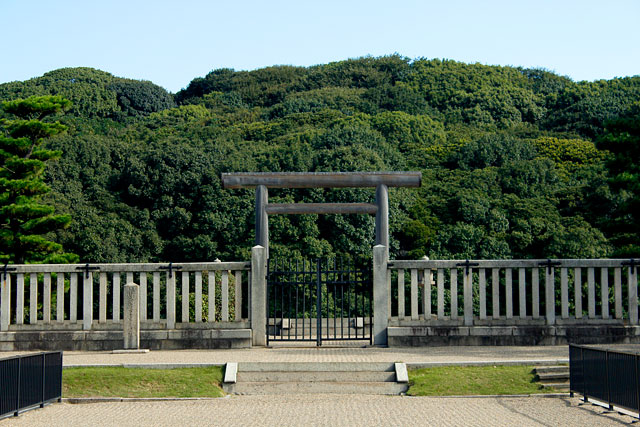

When viewed from the entrance gates, a tumulus would look no more than an average dense forest, with tall tree clusters. But only when one views the tumulus way up from the sky that he gets to marvel at the green-colored (or reddish during autumn), keyhole-shaped forest cover.

A painter who once drew a 17th century Sakai port viewed from the harbor—based on accounts of Dutch traders who sailed to Japan—depicted the city as a mountainous region, something the city is not. Scholars now believe that what the Dutch traders described to the painter was not a mountain, but the Nintoku tumulus with imposing trees sticking out of it.

Mr. Kurahashi, curator of the Sakai Museum, says the ancient rulers behind the majestic tumulus clusters did not originally intend to form them like giant keyholes, but over time the shape took on a new meaning. "As the royal family grew stronger, they decided to intentionally make keyhole-shaped tumuli as a symbol of power and authority," Kurahashi says.

And, he adds, the bigger your tumulus is, the more powerful and influential you are as a leader. For instance, Emperor Nintoku's tumulus is the largest one in the world, while just south of it is the much smaller tumulus of his son, Emperor Richu. And not too far from the two—on their east—is the second largest tumulus, made for Emperor Ojin, Nintoku's father and Richu's grandfather.

Kurahashi says tumuli are not reserved only for the male members of the imperial family, as empresses are also known to have been buried in similar, albeit smaller, grave sites. Just around the Nintoku tumulus are 16 other smaller satellite tombs containing other members of the royal family.

To this day, nobody dares to breach any of the tumuli, not only because they are considered private property (managed by the Imperial Household Agency) but because they are also highly regarded as religious sites believed to serve as sanctuaries for the spirits of the royal members buried here.

Tourists, and even the imperial family that owns the tumulus, could only go up to as far as outside the entrance gates, and never beyond them. When we visited the Nintoku tumulus, we even caught up with one local in front of the gate who was in deep concentration while chanting a prayer for the great emperor.

This inaccessibility is also the reason why tumulus clusters remain shrouded in mystery. With even scientists and archaeologists denied entry into the grave sites, nobody knows exactly what lies now behind their thick forest and beneath their terraced mounds.

Hisanori Kato, senior adviser for international affairs at the Sakai City Culture and Tourism Bureau, says the only instance in recent memory that people from the outside world were able to set foot on the Nintoku tumulus was when a great storm ravaged the city in 1872 during the Meiji Period and local officials had to get in the tumulus to assess the weather disturbance's damage.

And thanks to the typhoon, the locals unintentionally got a glimpse of the rich history embedded within the Nintoku tumulus. Kurahashi says local authorities who visited the outer portion after the 1872 storm unearthed a treasure-trove of historical artifacts—from ancient armors, helmets, glass bowls and plates to clay jars and terracotta in the shape of dogs or horses, called haniwa. Kurahashi says these artfully crafted wares were either "gifts" for or belongings of the deceased.

Even the emperor's stone sarcophagus is a work of art in itself—its shape resembling that of a traditional Japanese kimono, its vent-like tubes sticking out of the coffin's side, red circular ends symbolizing the sun. Similar clay jars, figures, and coffins are all displayed at the Sakai City Museum, along with miniature replicas of the city's famous tombs, as well as other ancient artifacts both from Japan and neighboring southeast Asian countries that show Sakai as a major trading community in east Asia.

Nowadays, Sakai City's centuries-old tumulus clusters remain untouched and preserved, standing out above all other structures in the horizon but at the same time co-existing and blending with the city's urban setting. Sakai City places great importance in preserving these tumuli, that until now the local government continues with its bid to have the cluster declared a World Heritage site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

So much has already been said about the world's more famous burial sites, but Japan's highly spiritual tumulus clusters remain shrouded in mystery.

Sakai's colossal tumuli—with rich Japanese tradition locked deep within its expansive grounds—could easily rival the pyramids or Taj Mahal... if only tourists could actually take a peek behind their dense forest and immerse themselves in centuries-old Japanese-style funerary rituals. — BM/HS, GMA News