A GMA News reporter's take on COVID-19 coverage

"Are you going to work?" My nine-year-old son Rocco asks in surprise.

I unintentionally disturbed him from sleep while I was gathering my things in the bedroom.

We slept late the night before, after playing board game Gloomhaven. Every night we fight monsters and villains while solving moral dilemmas in a dark fantasy world. We just started this ritual, which now has to wait until the middle of next month.

"But the virus! What?" My son pressed on, unconvinced that there was still work that I must do during the government-imposed community quarantine.

“Dada has to work. Otherwise no one else will know what is happening,” I said, giving him a buss on the cheek.

I turned and gave sleeping Patch, my eldest, a kiss in the forehead.

On my way to the office, I couldn't shake off the image of Rocco’s petulant expression and incredulous tone.

“But the virus! What?”

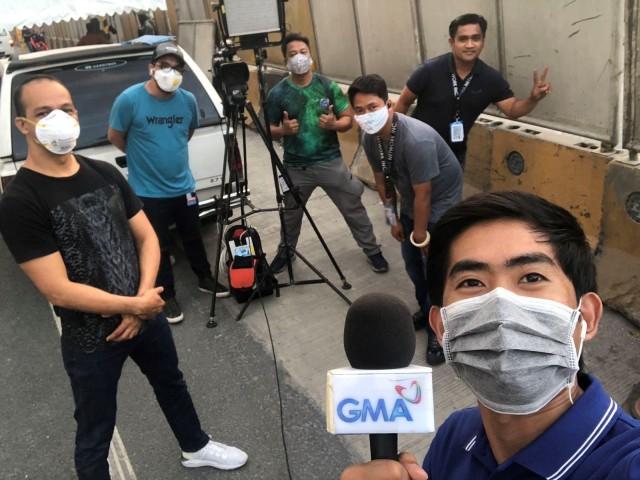

When most people were stay home due to the enforced community quarantine, journalists, along with those considered front-line personnel, are among the handful people that still report for work everyday.

GMA7 may have the intellectual property rights to use "24-Oras" (24 Hours), but most journalists in Metro Manila would be working round-the-clock.

Very few would take themselves out of the news cycle. Most of them will continue to write stories or meander around the metropolis to keep watch during these uncertain but historic times.

Journalism never stops for famine, fear, war, plague, and most likely, not even for the end of the world. Perhaps come the Apocalypse, there will most likely be a journalist writing down notes or shooting video when the Four Horsemen thunder across the skies.

Yet, prudence dictates that we scale back during these bleak days. News programs have gone off air and cable channels suspended operations as personnel found it increasingly difficult to report for work amid the checkpoints and danger, very real danger of coronavirus infection.

But ultimately it is the individual journalists who decide whether to go, or just stay home. Despite the risk and uncertainty, most of us chose to report for work.

“Uncharted territory ito. At sa araw-araw na paglabas, lalong tumataas ang risk involved. In war coverage, meron pang relatively safe areas. Dito hindi mo masabi talaga kung saan ang ground zero,” a veteran TV journalist from my network posted in one of our online forums.

Another journalist likens reporting for work during the lockdown period to a game of chance.

“Mababa lang naman ang fatality rate at pwede na ring mag-roll the dice. Parang tinatanggap ko na lang na matter of time, may tatamaan sa atin,” he said.

At times, news assignments carry risk and even direct danger. Journalists have come to cope with that aspect of the profession. We can lessen the risk by giving our journalists the correct knowledge and skill to survive hostile environments like war, and in situations of armed conflict. However, we have limited knowledge on how to keep ourselves safe, when the threat is unseen, a virus.

The Department of Health has issued guidelines on how people like journalists can keep themselves safe. Frequent hand washing, surgical masks, disinfectant, and the new and sexy byword "social distancing."

Combined, the DOH says, these steps can help lessen the risk of infection.

From our end, we already have a few teams up for quarantine after direct exposure to people who would later test positive for COVID 19. We say thankfully that none of us have tested positive and a few are already itching to go back to work.

The company has also provided living quarters for those fearful that they may be bringing the virus home everyday. Other news networks have done the same for their news personnel.

Beyond the business aspect and logistical challenges for news organizations, the dedication of journalists who remain in the field, carry a heavy, personal cost.

One seasoned journalist and his wife recounted their concern upon returning home to their parents after covering the quarantine checkpoints and DOH press conference.

“Ako sa giyera, madaling i-process yung mga kino-cover kasi alam ko, uuwi ako sa isang relatively peaceful place. Dito hindi. Nag-hit yan kagabi pag-uwi namin, di kami lumapit sa parents ng (asawa) ko, di ako makapagmano. Malaki epekto nito sa psyche ng mga tao long after matapos ang problema,” he said.

Early this week, my wife and I agreed I should temporarily move into the company billeting area. I told my kids, this was their father’s work but I also have to keep them safe by staying away until things return to normal.

On my second day of self-imposed exile, I went back to the house to pick up some sheets, towels and a care package from the kids --including homemade embotido, our bottled tuyo and some toiletries. These are things you take for granted on a daily basis, until they are all taken from you because of unexpected circumstances.

The household help handed me the bag outside my house. I wasn’t positive for COVID-19, and I did not have direct contact with anyone with possible infection. Or was I? I don’t know. There aren’t enough testing kits for me to know. So to be safe, there should be as little contact with my family as little can be.

My youngest son was on the third floor window waving goodbye at me and saying something I could not understand. He suddenly disappeared behind the curtains. I kept waiting for him to show his face again. He did not. My wife later told me that my son was already crying and did not want me to see him sad when I left that day.

I rifled through the stuff from home and saw a letter both from my sons, wishing me and my colleagues love and strength during these trying times.

"Hurry back," they tell me. "There are monsters yet to be slain and worlds to explore together, night after night. —LBG, GMA News